‘Do professional historians have a future?’ Honest History, 30 August 2016

Peter Mandler argued in his 2015 Aeon essay that the ‘crisis in the humanities’ since the 1950s has never existed except in the minds of humanities professors.[1] Yet people who work in the humanities have genuine concerns, even if Mandler is correct that the ‘crisis’ is overplayed. Mandler compares areas of teaching and argues that the humanities have, in fact, maintained their student numbers in higher education. [2] This argument fails to recognise the value of humanities research – the activity undertaken not by undergraduate but by postgraduate students – not merely as a means of ensuring the supply of academics, but because it produces practitioners for the society beyond the academy.

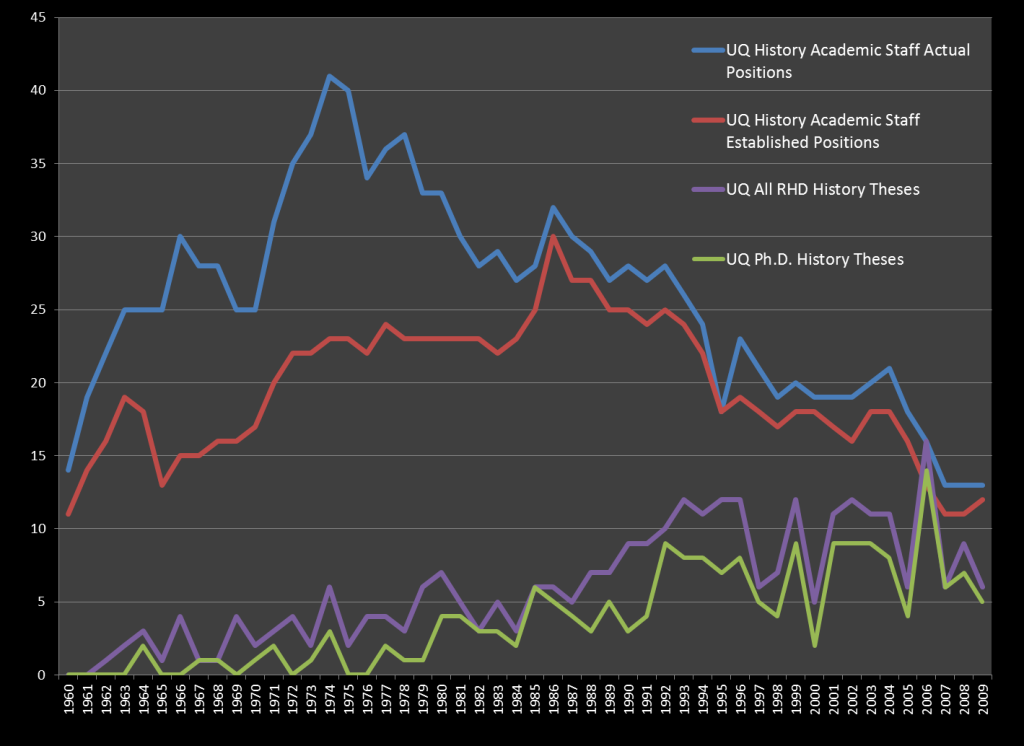

Within the broad humanities field, professional historians worry about trends in history education. Research on the University of Queensland has shown a curious phenomenon in a decline of history academic staff members since the mid-1980s, even though the number of research higher degree (RHD) theses requiring supervision increased during this period.[3] Each thesis submitted represented a history higher degree student who was a potential researcher in subsequent years.

Figure 1: University of Queensland (UQ) History Academic Staff and Research Higher Degree (RHD) Theses 1960-2009[4]

Figure 1: University of Queensland (UQ) History Academic Staff and Research Higher Degree (RHD) Theses 1960-2009[4]

There is a critical point at which the principle of economic efficiency fails. The declining number of established academic positions ought not to reach the point where it discourages potential practitioners from undertaking and submitting RHD theses, which is what we see (Figure 1) in the University of Queensland history unit in 2006-2009.[5]

The realities of working in research careers outside of academia have generally sunk in for the highly-trained practitioners in the humanities, including history. The problem is that reality has yet to catch up with the marketplace. Academic units (faculties and departments) are smaller; career options in universities are limited. This means that, if we are to have sustainable – employable – numbers of highly-trained researchers, then we need to grow the market outside of the universities.

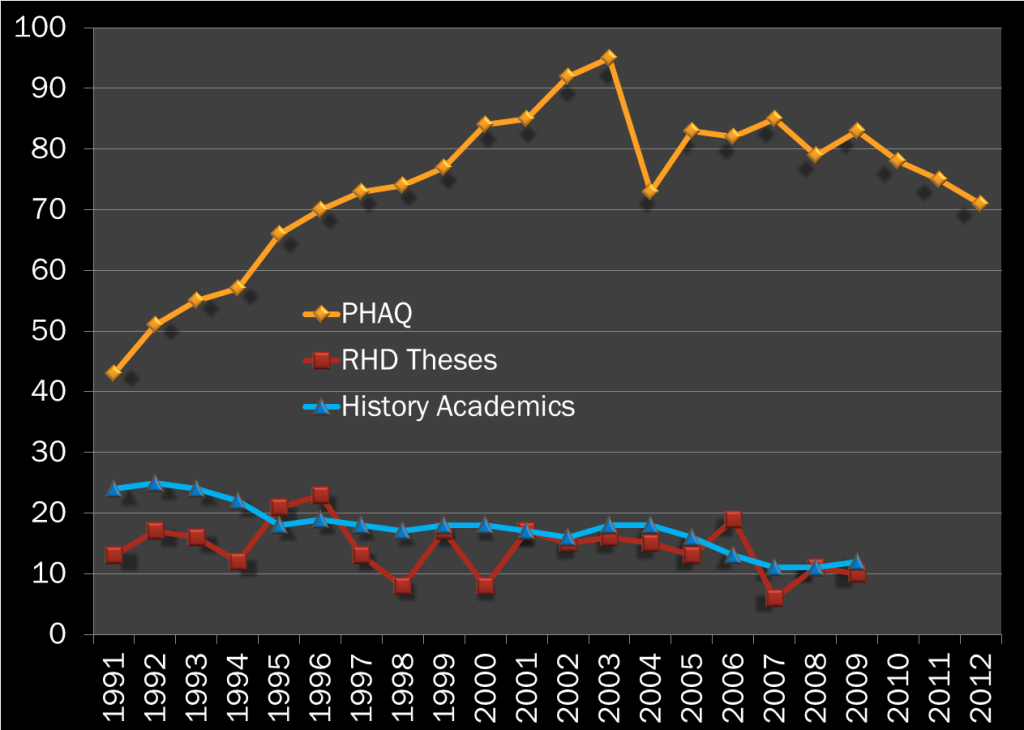

Growing the non-academic market has been a key concern of the Professional Historians Association (Queensland) and its predecessor, the Queensland Historians Institute, which began in 1989. Figure 2 shows the growth of these associations in Queensland in a time of declining numbers of academic historians and fluctuating numbers of RHDs.

Figure 2: Membership of the Queensland Historians Institute and the Professional Historians Association (Queensland) 1991-2012, compared with the Total number of Research Higher Degree Thesis at Griffith University, University of Queensland, and James Cook University of North Queensland, and the number of history academics at the University of Queensland

Figure 2: Membership of the Queensland Historians Institute and the Professional Historians Association (Queensland) 1991-2012, compared with the Total number of Research Higher Degree Thesis at Griffith University, University of Queensland, and James Cook University of North Queensland, and the number of history academics at the University of Queensland

Up to the turn of the 21st century the profession in Queensland had been able to absorb a growing number of early career history researchers. However, today – 2016 – there are serious questions about the sustainability of the profession. The trained historians of the future are to be found among postgraduate history students yet the numbers of these students are declining. In the last five years PHAQ membership has varied between 70 and 80 members, with the vast majority over 50 years of age. Many of these members are earning an income by contracting into underfunded history projects.[6] In recent years, though, there have been attempts to reconnect the professional association with the academic centres.

While the future is promising, we still need a cultural change if there is to be a sustainable marketplace outside of the tiny academic elite group. Although professional historians have been working with private clients for over two decades, a too-common expectation is that, if you want to earn an income from researching and writing history, you need to be an academic, employed at a university. The difficulty for professional historians in establishing a marketplace for public history is that this sort of history still comes largely from amateur historians – and that is the expectation of the market, which looks for empathetic accounts in biography, institutional history, or local studies.

Here arises the problem. As good as the works of amateur historians are they do not demonstrate the best from the contemporary discipline of history. More often than not historical accounts written by amateurs lack the kind of rigour applied by historians who have been trained in both the humanities and the social sciences. For example, professional historians are expected to be painstakingly careful to avoid inaccuracies with the historical evidence and to avoid misapplication through fallacies in the historical narrative.

Professional Historians Association (Queensland) logo

Professional Historians Association (Queensland) logo

There is a presumption that training in the contemporary discipline of history is unnecessary to produce good history books and other works for public consumption. Compared with the book sales of, say, Peter Carey, Peter FitzSimons and Tom Keneally, the books of professional historians who write for the public – Geoffrey Blainey, Henry Reynolds, Clare Wright, for example – have yet to do as well.

With some notable exceptions like the readers of FitzSimons, who have made him the best-selling non-fiction author in Australia in the last decade, the non-fiction book reading public is a small part of the overall book market. It is not that the scholarship of history cannot be entertaining. The challenge is that readers have been so conditioned to the drama of fiction that they find it difficult to appreciate the sheer delight of a past crafted or unpacked, as detailed descriptions and explanations, by a professional historian.

Historians and other humanities researchers face the same fate as the serious artist. On one hand, their work can be easily dismissed as a hobby, a bit of fun without any utilitarian value, and yet, on the other hand, it fails to compete against products which the market considers more entertaining. Journalists who write history are especially adept at exploiting their media links to obtain reviews of their history tomes, reviews which may be as entertaining as the books themselves but which show just as little understanding of the art – and the social science – involved in professional history.

Two factors are critical to our future as professional historians. First, we need to close the gap between the practitioners of academic history and the practitioners of academically-based applied history. This will connect the upcoming generation in postgraduate studies and the established generation working in the field.

Secondly, we need to grasp an important factor which underlies the stability in the numbers of professional historians. Here the concern is for the future of true humanities researchers, rather than historians diverted to social science outcomes, such as narrowly described heritage and property history work. The challenge remains that worthy, well-funded, academically-based public history outputs are still associated with the higher education academy rather than with professional historians. Meanwhile, the public have favoured – and purchased – the output of amateur historians, and so not perceived the quality of professionally-written history against lesser works. The survival of quality professional history requires educating the marketplace.

This article is a reduced version of a larger draft paper, and feedback has been provided by Dr Jonathan Richards, President of the Professional Historians Association (Queensland), Dr Catherine Manathunga, an educationalist historian from Queensland, working at Victoria University in Melbourne, and who has developed an expertise on postgraduate supervision, and Dr Jack Ford, a historian who has worked in the local heritage industry.

NOTES

[1] Peter Mandler. ‘Rise of the humanities’, Aeon, 17 December 2015, https://aeon.co/essays/the-humanities-are-booming-only-the-professors-can-t-see-it , viewed 22 August 2016.

[2] Mandler compares the humanities and the basic sciences, social science, allied health professional fields, ‘science, technology, engineering, and mathematics’ (STEM).

[3] Neville Buch. State of the History Profession in Queensland Project. 2012 Annual General Meeting of the Professional Historians Association (Queensland). Wednesday 26 September 2012; Neville Buch. A Preliminary Study of History Research Higher Degree Theses Numbers in Queensland: The Last 50 Years (1960-2009) at University of Queensland, James Cook University, and Griffith University. Professional Historians Association (Queensland), November 2011. Further unpublished statistical work done in 2014.

[4] The reason for counting both ‘actual positions’ and ‘established positions’ is to be able to understand the sustainability in employment for the History School. Actual positions include casual teaching and casual research appointments. Established positions are permanent appointments with continuing work titles (usually senior lecturer and above). What we see is that the growth in the History School, from the early 1960s to the mid 1970s, was supported by positions which had not been translated into permanent positions. In 1981, the restructuring of that university’s tutorial system saw tutorships become temporary appointments awarded to only a handful of postgraduate students. The early 1980s started to soak up absorb casual academic appointments into permanent positions, but a peak was reached 1985-86. From there, numbers of history academic staff members declined.

[5] RHD submissions as a measure has the advantage of not overlooking the common problem of postgraduate enrolment or admission numbers rising but graduate numbers not corresponding in a similar rise because of the failure of candidates completing thesis work. Often this is crucially a problem of the available academic supervision and support not being there because of insufficient academic positions.

[6] A small number of members of the Association (PHAQ) do continue to work in academic history, more often under short-term contracts. Among the consultants, a number work from time to time as collaborative private research entities, among fellow historians, or with archaeologists, architects and other heritage specialists. A few PHAQ members work as employees of government agencies, such as small heritage units, or at other public institutions, such as libraries and galleries.

Coincidentally, I found this American piece from the Inside Higher Education site.

It asks a similar question but from the American undergraduate perspective, stating as a header, “In the midst of a traumatic and turmoil-filled year, people seem to be crying out for historical perspective… But can that help save the profession?”

https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2016/08/18/history-vogue-media-even-college-majors-decline-essay?

As I argued, the profession can only be secured by the institutions working with the practitioners in educating the marketplace for academically-based public history. This is the kind of point that Jason Steinhauer makes, in the American context, from his call: “Historians have an opportunity this year to showcase the best and brightest aspects of our profession.” I think that it has to be more than the ‘showcasing’ of the meritocratic elite, and has to be aimed at the public association of well-funded, academically-based public history outputs from institutions working with proven practitioners. It seems to me that this is what other professions do in public-private collaborations with very little or no controversy.