‘Divided sunburnt country: Australia 1916-18 (10): Prime Minister Hughes announces the first conscription referendum, 100 years ago today’, Honest History, 30 August 2016

The ‘Divided sunburnt country’ series

Just after 3.53 pm on Wednesday, 30 August 1916, on a cold and showery Melbourne day, Prime Minister WM Hughes said this in the House of Representatives:

In view of certain urgent and grave communications from the War Council of Great Britain, and of the present state of the war, and the duty of Australia in regard thereto, and as a result of long and earnest deliberation, the Government have arrived at the conclusion that the voluntary system of recruiting cannot be relied upon to supply that steady stream of reinforcements necessary to maintain the Australian Expeditionary Forces at their full strength.

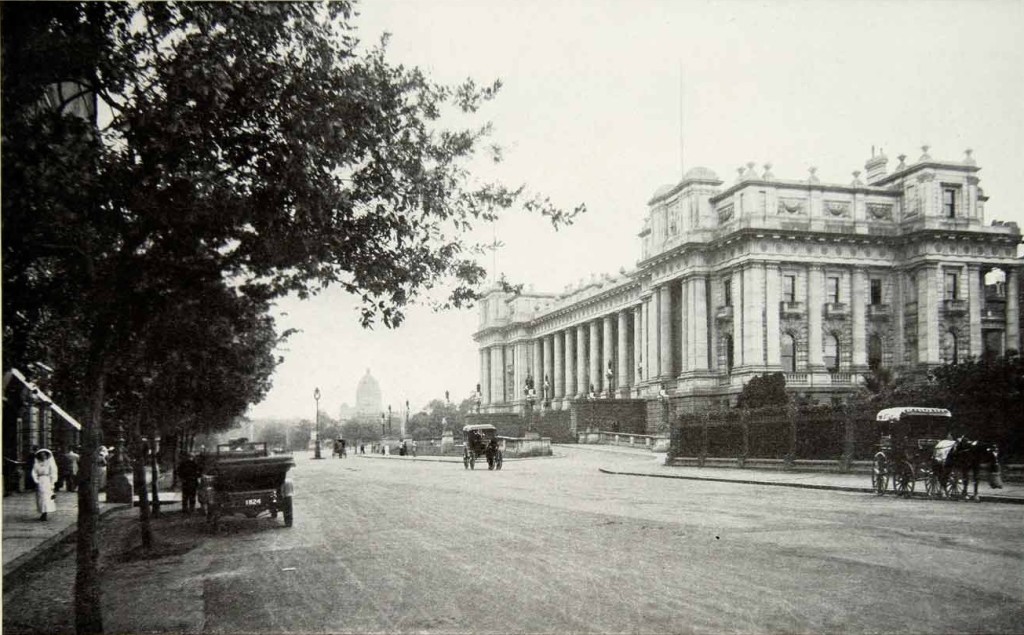

Commonwealth Parliament House, Melbourne, 1916 (PeriodPaper)

Commonwealth Parliament House, Melbourne, 1916 (PeriodPaper)

Enlistment numbers had fallen away: June 6375; July 6170; August (to 23 August) 4144. Yet casualties for the most recent 11 days were 6743.

[The figures] show that the position which confronts the Government, the Parliament, and the people, is that while it is our clear duty to keep the number of our Forces up to their full strength, the stream of recruits under the voluntary system has fallen to less than one-third of what is necessary.

The Somme offensive had ‘cost a fearful price’ but ‘[t]o falter now is to make the great sacrifice of lives of no avail; to enable the enemy to recover himself, and, if not to defeat us, to prolong the struggle indefinitely, and thus rob the world of all hope of a lasting peace’.

To the principle of compulsion for military training and service the country has long been committed. But a clear line has been drawn between compulsory service within the Commonwealth and service overseas. For the first we relied entirely upon compulsion; for the latter upon voluntaryism.[1]

But what was to be done? The failure of voluntary recruitment did not relieve Australia of its ‘obligations to the Empire, to its Allies, and to the Commonwealth … Though voluntaryism fails, the country must not fail.’

The Prime Minister then appealed to popular sovereignty.

But this is a country where the people rule; and in this crisis – in which their future is concerned – their voice must be heard. The will of the nation must be ascertained. Autocracy forces its decrees upon the people; Democracy ascertains, and then carries out the wishes of the people. In these circumstances, the Government consider there is but one course to pursue, namely, to ask the electors for their authority to make up the deficiency by compulsion.

The policy of the government was

to take a referendum of the people at the earliest possible moment upon the question whether they approve of compulsory oversea service to the extent necessary to keep our Expeditionary Forces at their full strength. If the majority of the people approve, compulsion will be applied to the extent that voluntaryism fails. Otherwise, it will not.

Meanwhile, he urged recruiters to step up their efforts and men of fighting age to enlist. He set out the supply and demand arithmetic.

If volunteers respond in sufficient numbers there will be no need for compulsion. But to the extent that voluntary recruiting fails to supply the numbers necessary the Government will use the authority of the people, if given, to call to the colours, until the supply is exhausted, single men without dependants. It is not intended, until the supply of single men without dependants is exhausted, to apply compulsion to married men, youths under twenty-one, to single men with defendants, or to the remaining sons of families in which one or more of the members have already volunteered.

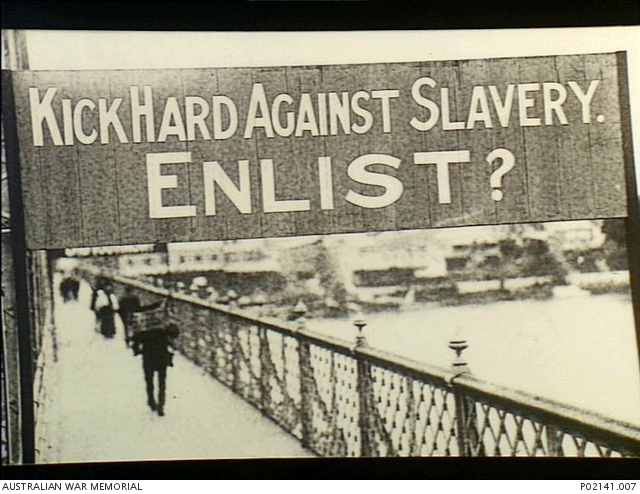

Recruitment effort, Brisbane, c. 1916 (AWM P02141.007/R.Pike)

Recruitment effort, Brisbane, c. 1916 (AWM P02141.007/R.Pike)

If volunteers did not come forward within the next month in sufficient numbers, single men without dependants would be called up by proclamation under the Defence Act, though the Prime Minister hoped that step would be unnecessary. ‘Unless and until the people of Australia approve of extending the compulsory provision of the Defence Act to service overseas, no man will be sent away against his will.’

The Prime Minister turned from logistics to patriotic rhetoric.

Sir, we are passing through the greatest crisis in our history. Our national existence, our liberties, are at stake. There rests upon every man an obligation to do his duty in the spirit that befits free men. The Government asks men to make a great sacrifice; it asks them to risk their lives in order to save their country.

He went on to talk about the need for equality of sacrifice, including the sacrifice of wealth. This had been an issue within the Labour movement at least since the War Census of 1915: conscription of labour, many Labour people argued, should mean also conscription of capital. That issue would be caught up in the campaign for and against conscription over the next two months, leading to the referendum on 28 October.

Hughes’ speech, says Joan Beaumont in Broken Nation (Kindle Location 3881), ‘began a public debate that has never been rivalled in Australian political history for its bitterness, divisiveness and violence’. It will be interesting, 100 years on, to see how much of this story is noticed by the official commemoration industry. (Beaumont’s chapter 3 provides a comprehensive story of the first conscription struggle.)

Finally, there were two elements of continuity between that day a century ago and later history, neither element all that significant, but both worth noting nevertheless. First, on the page of Hansard immediately preceding the Prime Minister’s speech, under public service promotions, there was announced the promotion of one JK Jensen to Clerk 2nd Class in the Central Staff of the Department of Defence. (In those days, apparently, such news was recorded in Hansard rather than in a separate Commonwealth Gazette.) John Klunder Jensen (1884-1970) later rose to great heights in the Commonwealth Public Service, heading the Department of Munitions during World War II.

Secondly, Hughes’ reliance on a referendum – which had come about mainly because he realised he lacked the numbers in the parliament to bring in conscription, and his protestations about the importance of consulting the public on this issue, have some echoes a century later on a very different issue with a very different prime minister.

[1] The Defence Act 1903 allowed conscription for home defence. It provided the legislative basis for compulsory military training for boys (not men) from 1911, described by Maxwell Waugh in Soldier Boys.

I got the 135 Swanston Street address from letterhead on documents in NAA: A463, 1962/3685 Part 2. Eg, there are a couple of letters starting at page 18 in the PDF version where that address was used in March 1967.

Its a trivial issue, so I won’t say anything more about it except this. It has reminded me that in 1969 when I registered you could go to a post office and pick up as many registration forms as you wanted. I filled in several forms with entirely fictitious details, as did many other people.

This is what we got from Archives:

https://honesthistory.net.au/wp/wp-content/uploads/Agency-Details-Dept-of-Labour-National-Service.pdf Shows DLNS at 37 Swanston Street 1953-58 then Commonwealth Centre then Flinders Street (I recall paying them a visit in 1970 or so). Jensen House is 339 Swanston Street. It’s possible I guess that bits of it were outposted eg to 125 Swanston Street but so far no evidence for Jensen House. Pity.

According to the ADB “In December 1969 the Victorian headquarters of the Department of Supply was named Jensen House.” During the Vietnam War the Melbourne office of the Department of Labour and National Service was in the Century Building at 125 Swanston Street. DLNS had been in that building at least since 1942: “Special Garb for Industry”. The Age, 8 July 1942, p. 2. https://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article206815123.

Thanks for that clarification. We were hoping that we could also pin down some evidence that Jensen House in Swanston Street at one stage in the 1950s and 1960s housed Department of Labour and National Service – in charge of the two conscription schemes during that period – but National Archives said this was not the case. Would have made the serendipity even neater.

The appointment of JK Jensen, mentioned in the penultimate paragraph, would have been made under section 31 of the Public Service Act 1902. That section allowed appointments to the public service without going through the usual procedures of examination, probation, etc. These appointments had to be tabled in parliament, whereas ‘normal’ appointments, promotions, etc only required gazettal: see section 76 of the Act.