‘”Charles Bean’s legacy”: UNSW Canberra conference, July 2016’, Honest History, 2 August 2016

For once in considering a conference, the curate’s egg judgment ‘good in parts’ doesn’t apply, though this conference did have parts and it was hosted by the former Anglican Bishop to the Australian Defence Forces. One part, however, was not planned.

Held on Friday and Saturday 29-30 July 2016 at the University of New South Wales Canberra, the conference was organised by UNSW’s Australian Centre for the Study of Armed Conflict and Society and convened by its Director, Professor Tom Frame (the former bishop), and an Associate Director, Professor Peter Stanley. Sadly, their colleague, Professor Jeff Grey, who had been scheduled to speak in two sessions, died unexpectedly three days before the conference started.

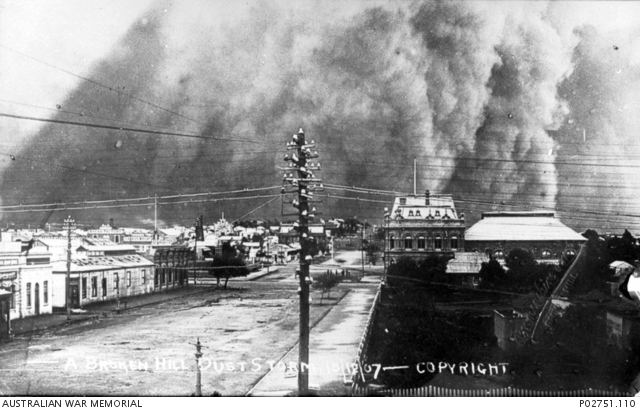

Broken Hill dust storm, c. 1907 (AWM P02751.110/Bean private collection). Bean travelled in Western NSW at this time.

Broken Hill dust storm, c. 1907 (AWM P02751.110/Bean private collection). Bean travelled in Western NSW at this time.

Such was Jeff’s standing among colleagues and his personal impact within the Centre that the organisers seriously considered not proceeding with the conference. To go ahead – and the sensitive way they responded – was impressive indeed.

It was decided to hold a mini memorial service in the first session Jeff was down to speak at (on ‘Bean and official history’), and rightly so, for it was clearly important, especially to the Centre staff who joined us then and also to the many others attending who knew Jeff well as friend and colleague. Led by the two aforementioned directors, the speakers included other Centre people, Andrew Blyth and Associate Professor Mesut Uyar, a former ADFA Commandant and retired Rear Admiral, James Goldrick, former students Garth Pratten and Colin Garnett, and fellow historians Peter Dennis, Craig Stockings, Roger Lee and Tom Richardson.

A second conference addition, however, was planned – an exhibition opening, and what was billed as ‘An evening inspired by Bean’. The former saw the renowned Bean biographer, Peter Rees, open the exhibition, ‘Charles Bean: life and work’, featuring items lent by Bean’s granddaughter, Anne Carroll, supplemented by material from the National Archives and the exhibition host, the Australian Defence Force Academy Library. The exhibition runs until October and will be separately reviewed for Honest History, but let’s say in passing that it is highly recommended, including as it does material never before publicly seen.

The Bean-inspired offerings were music especially composed and performed (voices from Canberra Girls Grammar School and piano) to complement the conference program – essentially responses to Bean’s poem ‘Non nobis’ – and a showing of Wain Fimeri’s 2010 film, Charles Bean’s Great War. After the performance there was an ‘in-conversation-with’ exchange with the chair, Tom Frame, and after the film, a brief Q&A with the producer.

I was left in two minds about the exhibition music and film, though I appreciated them all. They were clearly the results of much thought, effort, creativity and planning, and, had they not been scheduled with little pause at the end of a long, cold and challenging day, and in two venues separate from the conference theatre, my reaction then and reflection now probably would be different. Bean’s ‘Non nobis’ could have anchored an entire session on his religious attitudes or – thinking of his bust, portraits and Bruce Scates’s novel, On Dangerous Ground – on what insights creative artists may offer in capturing Bean.

Day One

As to the conference proper, the focus on Friday was all Bean: as chronicler, creator (of archives), historian and subject. The specific details as to who spoke on what are available from the program. What follows is thematic, rather than a catalogue of comments on each of the 15 presentations.

Bean, c. August 1919 (AWM P04340.004/Gift to CB White)

Bean, c. August 1919 (AWM P04340.004/Gift to CB White)

On Bean, most speakers focussed narrowly: Bean and … the Western Front, his philosophy of history, his scattered archival material, his time at Tuggeranong, and his role in national archival initiatives. Two speakers painted bigger pictures, one sharing a reflective auto-historiographical account on re-reading Bean’s multi-volume war history, and the other addressing the ultimate biographer’s task of fully and insightfully capturing who Bean was.

Combined, these papers revealed so clearly the rich complexity of Bean as a biographical subject, despite a natural tendency to frame him through war. During the end-of-day panel session, the half dozen sidelights of his career and achievements already covered were supplemented by Justice Geoff Lindsay, coincidentally a serving New South Wales Supreme Court judge keen to champion Bean’s key pre-war monographs and autobiographical writing, having previously published on Bean’s brief time as a barrister and judge’s associate. There Lindsay had also discussed Bean’s moral and religious world, a matter further covered by Tom Frame and Craig Wilcox in this last session.

As is their nature, these sessions revisited familiar issues, for example, Bean’s dislike of Monash and Blamey and of the English class system. But new questions emerged too: How strongly can we draw parallels between Bean’s life, philosophy of history and blind spots with those of Manning Clark? What will the next generation of Bean studies cover? Did Bean suffer a form of post-traumatic stress disorder?

Day Two

Day Two covered Gavin Long and the subsequent official war histories, though the day was still conceptually overshadowed by Bean, through sessions on establishing the Australian war history tradition as well as examining its evolution and continuity.

There were still differences. First, the continuing presence of Jeff Grey in the planned program was manifest through a reading of his paper ‘Konfrontasi’, arising from one of his volumes in the so-called ‘Southeast Asian conflicts, 1948-1975’ official history. A different kind of absence involved Bob O’Neill, the Korean War official historian, who participated virtually through the broadcast of a pre-recorded interview answering questions by the conference organisers with the program themes in mind (long version). O’Neill’s anecdotes included mention of Wilfred Burchett, and they were as fascinating and chilling as were some of Peter Dennis’ relating to the Malayan Emergency, particularly about the leader of the so-called ‘CTs’ (communist terrorists), Chen Peng.

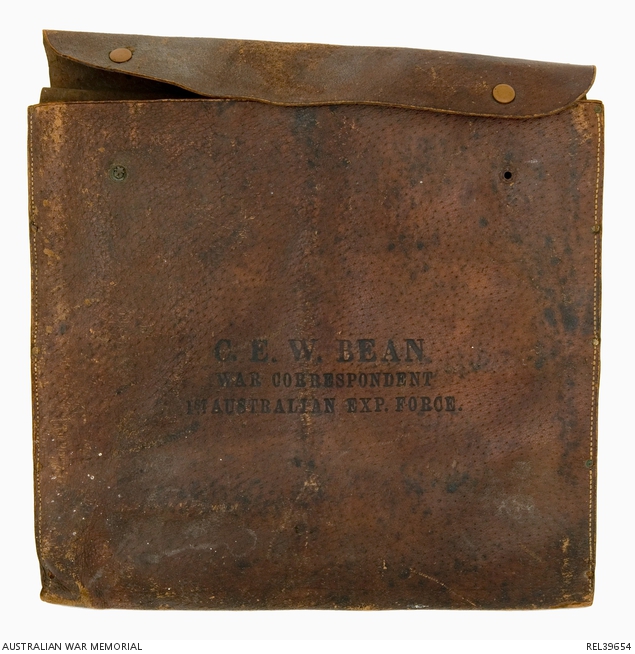

Bean’s satchel (AWM REL39654)

Bean’s satchel (AWM REL39654)

Secondly, while on Day One Bean had been so palpably in evidence through his latest and best biographer Peter Rees, Bean’s granddaughter, and the exhibits, music and actors, on Day Two the direct testimony of all his successors (with the exception of Gavan Long) was available. As well as general editors Peter Edwards, David Horner and Craig Stockings, several official and other historians also spoke.

Throughout these sessions and in the second end-of-day panel discussion, the conference did tackle the question of Bean’s legacy and the degree of continuity. All agree now no-one wants to or is required to see war as the test of a people’s character and as a nation-building project. And Gavin Long? Everyone deplored his neglect by biographers, but beyond that, some considered him – regardless of how he regarded Bean and was indebted to him – as establishing the Australian official war history tradition. Others saw Bob O’Neill’s two volume Korean War treatment, which split strategy and diplomacy from operations, as a new standard. All also agreed that the nature of conflicts in which Australian forces are now officially involved, particularly peacekeeping and related operations, undermine any notion of a fixed Bean tradition.

Reflections

Within days of the conference concluding, two participants had circulated emails telling of project plans triggered or encouraged by attendance and discussion at the conference. The conference’s impact more generally may become clearer once the papers are published by UNSW Canberra in the first half of 2017. In my own mind, though, there are several ‘impressions-in-progress’.

It seems that the Australian War Memorial boycotted ‘Charles Bean’s legacy’, its only participant being Peter Burness, rightly honoured last year as a Fellow of the Memorial. The Memorial also declined to contribute to the ADFA Library Bean exhibition. Why would an agency whose history is so intimately linked with official histories and Bean’s life and papers behave so? One imagines that, at the Memorial’s international history conference, 1916: The Cost of Attrition, held the previous week between 20 and 22 July, there were innumerable references to Bean. The lack of Memorial involvement in the UNSW Canberra conference was counterproductive and certainly detracted from the conference.

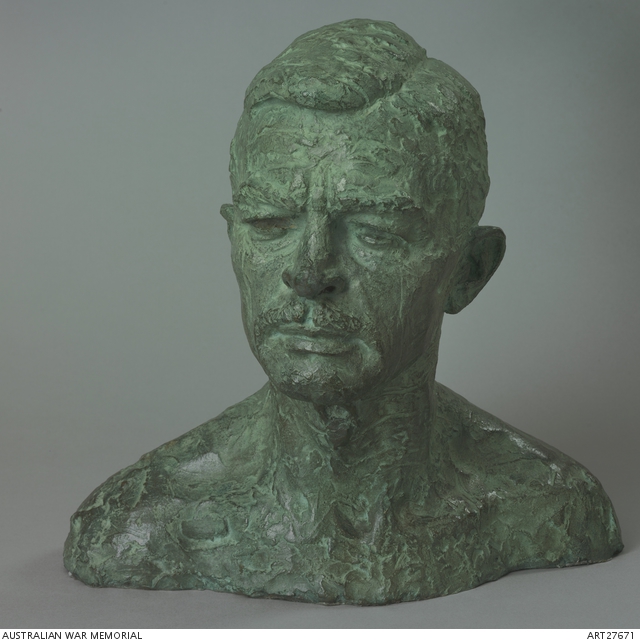

Gavin Long (AWM ART27671/John Dowie 1970)

Gavin Long (AWM ART27671/John Dowie 1970)

A second reflection concerns the calibre of our official war history general editors. (For the basic details, see historical and recent information on the Australian War Memorial website, as well as this post summarising the story.) The first two editors were journalists turned historians, but the editors are now increasingly ex-Australian Defence Force academics. All, however, have faced challenges additional to the writing, itself daunting enough in terms of expectations, the extent of sources and time pressures. All at times have needed high-level negotiation skills, judgement in selecting subsidiary authors and researchers, and steely determination in pursuit of access to information and resources.

As well, all have aimed at accuracy, benefiting from almost total access (signals intelligence being the usual exception) yet knowing research in subsequent decades will prompt updates, corrections and qualifications to their own inevitably time-bound conclusions. Peter Edwards in particular acknowledged this reality in his presentation about the Vietnam official history, and in follow up questions defended its third volume (by O’Keefe and Smith) on medical aspects of Australia’s involvement in Southeast Asia 1950-72. He clearly has a point and, to me, the Memorial’s commissioning of a new volume on the medical issues experienced by Australian veterans, with particular focus on PTSD and the health effects of exposure to herbicides, is a curious and precedent-setting decision. (The events leading up to this decision are covered in an article by Jacqueline Bird.)

One completely consistent official history requirement has been the creation, location and selection of, and access to relevant documentation, and this thread ran throughout the entire conference program. From Bean to Stockings, military records have been critical but Garth Pratten’s penultimate conference paper, ‘History in the digital age’, describing what all that means in the 21st century, was a genuine highlight. Garth made a passionate appeal for better attention to documenting modern warfare, interweaving experiences from his time with the British Ministry of Defence, when attached to the team compiling the war diary for NATO’s Regional Command South, Afghanistan. Recalling the Australian War Records Section’s 1917 injunction: ‘REMEMBER! a well kept diary is the surest pledge to future recognition’, one concluded that some basics never change. Nor, indeed, does the rule which holds that a conference with strong content cannot fail.

Robert O’Neill (Daisy Alliance)

Robert O’Neill (Daisy Alliance)

Michael Piggott’s own paper, ‘The distributed Bean archive – bigger than we’ll ever know’, was described by knowledgeable and appreciative attendees as one of the highlights of the conference. HH