‘Is Asia closer to war than at any time in recent history – and do we care enough about this?’ Honest History, 28 September 2018

Richard Broinowski reviews The Four Flashpoints: How Asia Goes to War, by Brendan Taylor

Brendan Taylor’s thesis is that Asia is closer to war than at any time in recent history and that the protagonists are dangerously complacent about this. His case is well-argued and generally soundly based on research; his book is a timely and useful analysis of a set of long-standing regional frictions.

Taylor’s four flashpoints are the Korean peninsula, the East and South China Seas, and Taiwan, and he bases their status on three criteria: long-standing disputes, geographical proximity, and powerful actors. Korea is a flashpoint because of Kim Jong-un’s successful nuclear weaponisation program, which is fiercely opposed by the United States, Japan, and to a lesser extent, the Republic of Korea. Taylor’s well-founded concern is that if President Trump’s coercive plans to denuclearise the peninsula – that is, persuade Kim to destroy his arsenal – do not succeed, he may seek to end, by military means, both Kim’s program and his regime.

Taylor’s four flashpoints are the Korean peninsula, the East and South China Seas, and Taiwan, and he bases their status on three criteria: long-standing disputes, geographical proximity, and powerful actors. Korea is a flashpoint because of Kim Jong-un’s successful nuclear weaponisation program, which is fiercely opposed by the United States, Japan, and to a lesser extent, the Republic of Korea. Taylor’s well-founded concern is that if President Trump’s coercive plans to denuclearise the peninsula – that is, persuade Kim to destroy his arsenal – do not succeed, he may seek to end, by military means, both Kim’s program and his regime.

The East China Sea is a flashpoint because conflicting Chinese and Japanese claims to the Senkaku-Diaoyu islands prompt increasingly dangerous and more frequent manoeuvres by the Chinese and Japanese air forces and naval units. A clash, intended or otherwise, between these powers could rapidly escalate into a major conflict, encouraged by mutual historical antagonism.

Taiwan is subject to increasing volatility because its president, Tsai Ing-wen, does not hide her preference for the island to be recognised internationally for what it is, a free and democratic country of 23 million people independent of China. She openly declared this in a speech during a recent stop-over at the Ronald Reagan Library in Los Angeles on her way to Paraguay and Belize, the last two Latin American countries which still recognise Taiwan.

Across the Taiwan Strait, China’s president Xi Jinping is more impatient than his predecessors to absorb Taiwan into the Peoples’ Republic. He perceives that the US may not be prepared to defend Taiwan as resolutely as it did during the Cold War, and this may give him an incentive to take the island by force.

The South China Sea has become a potential target for several littoral states with territorial claims. According to the nine dash line invented by Chiang Kai-shek in 1947 (but adopted by the Chinese Communists) China and Taiwan both claim the whole Sea and all islands within it. Vietnam claims the Spratlys and Paracels, while Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei have each declared exclusive economic zones over parts of the Sea. The Philippines claims the Scarborough Shoal between the Macclesfield Bank and Luzon.

Apart from nationalistic hubris, rivalry is also driven by economic factors: the South China Sea is rich in fish, oil and gas. A provisional code of conduct was negotiated between the parties in 2002 but did not resolve contending claims. China, Taiwan, Vietnam and Malaysia have all installed military assets on the islands they occupy. In 2016, the Permanent Court of Arbitration denied China’s claims to 90 percent of the area, a non-binding decision China rejects. Meanwhile, armed clashes of varying severity continue.

Predicting the future is for the brave but, to his credit, Taylor attempts to prioritise his four flashpoints from the most to the least likely. Given Xi’s growing intolerance over Taiwan’s status and Tsai’s declaration about Taiwan’s independence, Taylor thinks Taiwan is the place most likely to ignite into open warfare. Taiwan may be able to hold off a Chinese invasion with American assistance but, given President Trump’s prevarications and muddled thinking, that US assistance would be forthcoming or successful is far from certain.

Second most likely is war on the Korean peninsula but, as Taylor observes, any attempt by the US to militarily coerce Kim to disarm could lead to a North Korean missile and artillery attack against Seoul and possibly Japan or Guam. Casualties would be massive. Given Trump’s continuing faith in Kim’s intention to disarm, and the third presidential meeting this month (September 2018) between Kim and Moon, the possibility of open conflict seems for the present to be receding.

The situation continues to be touchy, however. What could prompt Kim into action would be evidence that the US wants complete nuclear disarmament without any reciprocal compensation, such as a peace treaty or a guarantee not to bring about regime change in Pyongyang.

Taylor sees conflicting territorial claims in the East China Sea as third most likely to ignite into open warfare. It could happen, but Japanese and Chinese commanders are conscious of the risks and can be expected to exercise tight control over their forces. Finally, Taylor sees conflict in the South China Sea as least likely of the four possibilities.

Taylor concedes that it is all a guessing game, made dangerously uncertain by general complacency and the unpredictability of key players such as Kim Jong-un and Donald Trump. He cites as an appropriate metaphor Coral Bell’s ‘crisis slide’ that led to both the world wars.

One prediction Taylor does venture, however, is that the only clear winner in any contest would be China, a view shared by such eminent Australian China watchers as Steve FitzGerald and Hugh White. Joining in their chorus is another former Australian Ambassador to China, Geoff Raby.

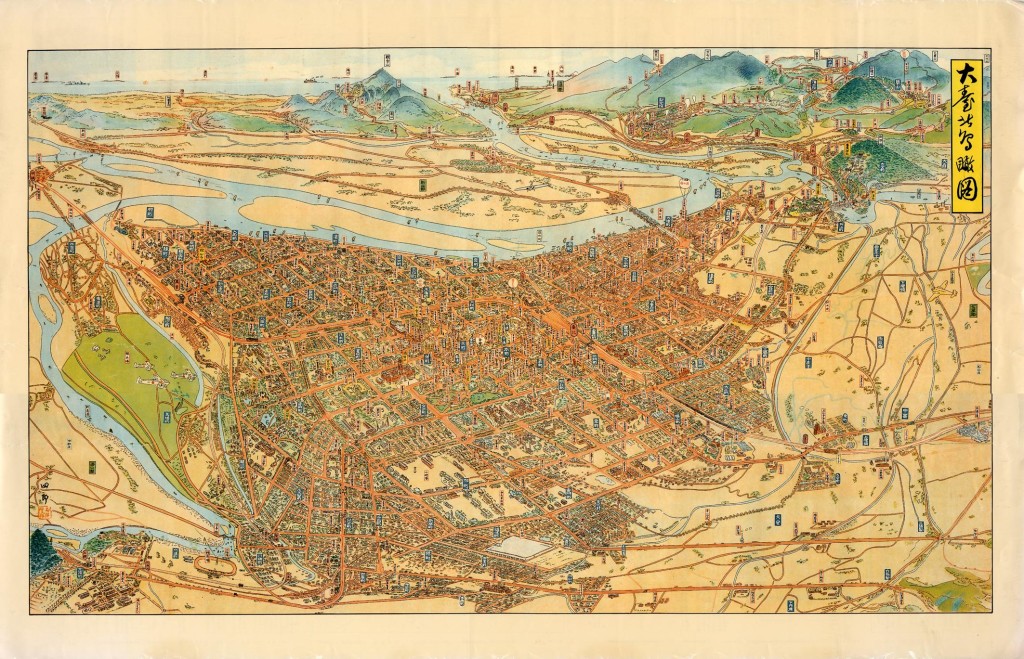

Birds-eye view of Greater Taipei, Taiwan, 1935 (Taiwan News)

Birds-eye view of Greater Taipei, Taiwan, 1935 (Taiwan News)

An opposing view, prevalent among political conservatives and echoed in the Canberra foreign policy bureaucracy is that India, Japan, Australia and the United States – the ‘Quad’ – could successfully contain China in the region. Perhaps, Taylor suggests, Asia’s most viable option is somewhere between China taking all and these other powers maintaining their interests in Asia.

Taylor’s thesis is persuasively reinforced with the historical reasons for enmity: China’s humiliation at the hands of European and American colonialists in the 19th century and Japan in the 20th, Japan’s colonisation of Korea, and China’s overbearing attitude towards Vietnam. He presents particularly well-researched material on why territorial disputes have erupted, especially over the Senkaku-Diaoyu islands and the Spratlys and Paracels. His book is a timely and thoughtful contribution to what is sure to become an increasingly urgent debate.

* Richard Broinowski is a former Australian Ambassador to Vietnam and South Korea. For Honest History he has written about the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Long Tan during the Vietnam War and reviewed Elizabeth Tynan’s book Atomic Thunder on the Maralinga atomic tests. Honest History has followed developments in the areas Taylor covers; try key terms in our Search engine to find useful resources.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.