Remembrance Day (Armistice Day, if you prefer) – like Anzac Day, Christmas, Easter, Passover, Ramadan, Diwali, Melbourne Cup Day, and other regular ceremonial and commemorative occasions – triggers virtually automatic reactions among many of us. Poppies, stories of old Diggers, a minute’s silence (if we remember), choking up over an item half-way down the evening news.

Remembrance Day could also make us think. Douglas Newton, Honest History distinguished supporter and historian of the Great War, has a thought provoking piece today on John Menadue’s blog Pearls and Irritations. (Menadue is also among Honest History’s distinguished supporters.)

Newton’s piece is called ‘Armistice Day – narrow nationalist naiveties and voodoo vindications of war‘.

Every year [says Newton], in the days leading up to Armistice Day, a little crop of opinion pieces appear urging Australians to do more than merely remember the dead of war. Various writers argue that we should also recognise the justice of the cause. These frankly nationalist opinion pieces are based on a naïve understanding of the Great War.

Newton takes a detailed look at the causes and motivations of World War I and comes back to that perennial question – whether the dead in war ‘died in vain’.

The “in vain” card must be one of the most contemptible cards played in politics. We are told that only victory can save the dead. It is a voodoo vindication. People die needlessly in war – “in vain” – in every conflict, every day. The idea that victory will redeem their deaths is preposterous. Wars must go on, the parents and survivors are told, lest the dead have died “in vain”; the truth is that wars must end, lest more men die for the vanity of politicians. There is indeed much to remember on Armistice Day. But we can do without the narrow nationalist naiveties.

Poppies, Federation Square, Melbourne, 2015 (ABC)

Poppies, Federation Square, Melbourne, 2015 (ABC)

Then there is journalist and author, Mark Dapin, writing in Fairfax, reporting his talks with retired soldier Ken Corke, who runs Australia’s Office of War Graves, within the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA). Dapin met Corke on a battlefield tour of the Western Front – Honest History noted the tour (scroll down to 25 October update) – and then again recently in Canberra.

I was impressed [in France] by his sincerity, and his endearingly anxious bonhomie, but disturbed by the thought that the Anzac commemoration had become less about remembering the devastation of global wars and more about applauding the idea that Australians were pretty good at fighting them.

Dapin probes further and brings out Corke’s misgivings about modern wars and even about World War I. But there is still a need to keep that war close.

For Corke, the graves of the fallen of 1914-1918, in particular, will be looked after only for as long as governments feel the political imperative to do so. Therefore, it is vital to preserve and encourage public interest in, and knowledge of, their war.

Both Douglas Newton and Mark Dapin have chapters in The Honest History Book. Newton’s is ‘Other people’s war: The Great War in a world context’. Dapin’s is ‘”We too were Anzacs”: Were Vietnam veterans ever truly excluded from the Anzac tradition?’

Talking of poppies, art historian Ann Elias writes in The Conversation about the significance of poppies in remembrance. Then there was this piece yesterday from history educator, Kim Wilson, also in The Conversation, on the need to teach children critical thinking about Remembrance Day. We were particularly interested in the report of a British study which ‘found that the historical monuments [at Ypres] elicited such a strong emotional reaction from the students that it impaired their analytical skills, which were otherwise well developed in relation to other kinds of historical accounts’. We have noted many times the obsession of the commemoration industry with getting emotional reactions from students – and adults. Perhaps this is why. (See this related piece from 2016.)

Wilson also has this perceptive paragraph:

As historical tourists attending commemorative services, students (and the adults they grow into) are at risk of accepting without question nationalistic and political agendas that may not be in their best interests. I want my students and pre-service teachers to recognise the political, social, and economic factors that influence how a society conducts and participates in memorialisation of the past. Recognising and understanding this influence leads to active and proactive citizenship.

Finally, with Remembrance Day relevance: we have recently posted a report on DVA’s program to deliver contributed content to regional Fairfax papers to prepare the ground for a flurry of commemoration during 2018; a Gippsland man, Jeff Glover, took war ‘storian Peter FitzSimons to task; Adelaide historian, David Faber, critiqued a Christian Zionist interpretation of the Great War, particularly Beersheba, and David Stephens disagreed with Bill Shorten about the Australian War Memorial.

Courtesy of Joan Beaumont, Broken Nation: Australians in the Great War

Courtesy of Joan Beaumont, Broken Nation: Australians in the Great War

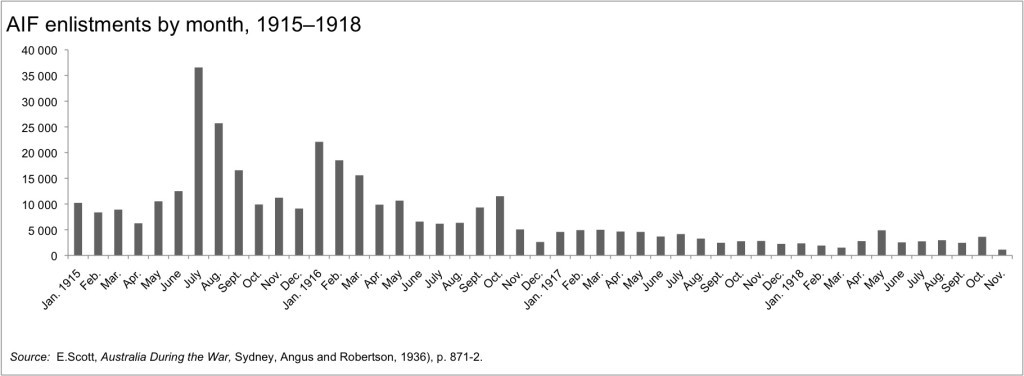

We also remembered, unlike most of the mainstream media, that this week was the centenary of the beginning of the second conscription campaign of 1917 and of the Bolshevik October revolution in Petrograd. Which explains the relevance of the graph above: war remembrance does not necessarily translate into willingness to feed more men and women into the monster of war.

Update 15 November 2017: more Remembrance Day material.

11.00 am 11 November 2017 updated

Spot on …. one of the most insightful (and expansive) pieces related to Conflict Commemoration that I have seen this year. Good one, David.