In 1917 GEM (Eric) Jauncey was a victim of war paranoia in his employment at the University of Missouri. The security services of the Hughes Government in Australia had been in touch with their American counterparts who paid a visit to Eric’s university and Eric found himself out of a job as a result of his indiscreet remarks in intercepted letters home to Adelaide and to his students and colleagues in Missouri.

Interior of Library, Iowa State College (later University), Ames, Iowa (Wikimedia Commons, photographer and date unknown)

Three years later, Eric is writing to Prime Minister Hughes from Eric’s job in the Department of Physics at Iowa State College, Ames, Iowa.

The letter contains an exposition of the perceived rights of British citizens as well as an indication of the discomfort felt by a man who is probably not a natural rebel but just wants to go home.

In what the letter shows of Australian official attitudes it also suggests that it is not only the Anzac spirit that has a long history.

Now read on …

505 Burnett Ave.,

Ames, Iowa.

June 1, 1920.

The Rt. Hon. W. M. Hughes,

Prime Minister of Australia

Melbourne, Australia.

Dear Sir:

I am writing to inquire as to whether you will be so kind as to order that a passport be issued to my wife, child and myself to enable us to return to Australia. For the past three years I have tried at various time to obtain a passport to Australia but on each occasion the authorities there have refused.

The last time I applied was in February 1919, some three months after the signing of the armistice. At that time the British Consul General at Chicago issued the passport, but, before I could receive the passport, it was revoked at the instance of the Australian government for reasons not stated. I am utterly at a loss to explain why, now that the war is over, it is that sojourn in my native land, which is also the native land of my wife, is denied to me.

I have asked Mr. Henry Berry of Annesley Avenue, Adelaide, South Australia to make inquiries on my behalf and I believe he has been in communication with either you or some other member of the Australian government. So far however nothing seems to have been accomplished and hence this personal letter to you.

It seems that the objection to my return to my native land was that my views on the recent war, as disclosed by my private letters to my private friends and relatives in Australia, were not approved by the government. I do not wish to present any argument as to my views on that matter because I wish to stand upon my right as a British subject and an Australian to have any views I wish.

Freedom of opinion is one of the Britisher’s most treasured heritages. In time of war, it is obviously the privilege of the government to restrain to some extent the freedom of expression. A government cannot, in such a time of stress, distinguish between the opinions of those who oppose the war because they favor the enemy and those who oppose the war for reasons which are just as patriotic and loyal as those for which others favor the war. The only question which might be in the mind of the Australian government is whether I favored the enemy. This is absolutely ridiculous.

My father, who was an Englishman by birth, served as a marine in Her Majesty’s Navy somewhere in the years 1880-1885. I believe he served in H.M.S. “Nelson” and H.M.S. “Orlando”. My mother was an Australian born of English and Scotch parentage. In the case of my wife, her father was born on the way out from England and her mother was an Australian, born of English parents. Further when my wife and I were in England in 1912-13 on our honeymoon we stayed with her uncle at Idle Bradford [West Yorkshire].

There is hence no doubt as to the fact of my wife’s and my British lineage. The views we held were those held by hundreds, if not thousands, of patriotic Englishmen in England during the war. I believe at one time during the war that Lord Northcliffe objected in his newspapers to some suppressive action against the pacifist press by the English government. He said that a certain amount of criticism of the government was not only advisable but necessary, even from the government’s own point of view.

However, the war is now over and certain restrictive measures which may have been necessary during the war certainly are not necessary now. The war was fought to establish freedom and democracy through-out the earth. What are freedom and democracy except as they mean freedom of opinion. I believe Australia, in spite of recent actions in regard to my own self, is one of the most democratic and free countries of the earth. Australia has pointed the way to the rest of the world in a number of ways. While in the United States as a teacher of physics, I have talked about public ownership and allied subjects in Australia. I have also written a number of articles on public ownership and other Australian experiments. In other words I have written and talked of what the Australian Labor party has done.

I left Australia in 1912, when I proceeded to England. I am a graduate with first class honors in physics of the University of Adelaide. In England I did research work in physics. In 1913-14 I taught physics at the University of Toronto, Canada. In 1914-16 I taught at Lehigh University, South Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, U.S.A. In 1916-18 I taught at the U. of Missouri. Now I am teaching at Iowa State College as will be seen by the above letterhead.

William J Flynn, Director of the US Bureau of Investigation (predecessor of the FBI) 1919-21. The Bureau had co-operated with Australian security officials against GEM Jauncey in 1917 and Jauncey was presumably still ‘on the books’ in 1920 (Wikipedia)

William J Flynn, Director of the US Bureau of Investigation (predecessor of the FBI) 1919-21. The Bureau had co-operated with Australian security officials against GEM Jauncey in 1917 and Jauncey was presumably still ‘on the books’ in 1920 (Wikipedia)I have had no quarrel with the U.S. government during the war, with the exception that I had to resign from the U. of Missouri because extracts from letters of mine which were opened in Australia before the U.S. entered the war were presented to the governing authorities. Since the war has ended there has been no objection to my teaching again in the U.S. Upon the entrance of the U.S. into the war, I like a number of other people bowed to the will of the majority and in no case did I make any public expressions or perform any actions detrimental to that will. I didn’t agree with it but in the vernacular I had to lump it. What I said in my private letters home should be treated as private conversation.

I have had a lot of experience now which I think would be of value to Australia. There are several points about the method of teaching physics in the U.S. which I think might be adopted in Australia. I believe that because of this and similar other things I have learnt by experience that I would be a valuable addition to the citizenship of Australia. It was my object in 1912 when I left Australia to be away about 5 years getting experience and after that to return to Australia with the object of giving Australia the benefit of my experience.

I have no desire whatever to remain in the United States. I believe that as far as liberty and democracy is concerned Australia is far ahead of the United States. Then, too, the climate of Australia is much more desirable than the extremes of heat and cold which obtain in most parts of the United States. Further, we have a little girl who will be six years old in September 1920 and who will then begin school. It has always been our desire to have her brought up as an Australian rather than an American.

Still further, both my wife and I had the influenza in December-January of 1918-19. The ‘flu left us both in rather a bad state. We both suffered a sort of nervous frustration. We were here in this country all alone with no relatives and no very close friends. We have no desire to be up against a proposition like that again. I was unable to work for seven months and all told the influenza together with its effects set us back some $1,500. If it had not been that we had some money in the bank, I don’t know what would have become of us.

It was not until a year after having the influenza that I felt either competent or confident enough to undertake teaching in a university. Again, still further I have property in Adelaide which is part of a trust estate left by my grandfather and where one’s property is there is one’s heart also.

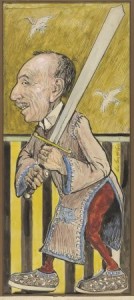

William Hughes as Ko-ko, Lord High Executioner in The Mikado, 1923 (National Library of Australia, nla pic-an6570524-v; pen and wash drawing, GA Taylor)

In view of all the above I must repeat that I am at a loss to understand why access to my own country is still denied to me. I would be much gratified to you if you would look into, or would cause someone to look into, this matter. Of course I am a supporter of the Australian Labor party, but I can’t imagine that that fact would be any reason for keeping me out of a democratic country like Australia.

The war is now over and the hatchet should be buried. During the war passions ran high. I believe all of us under the strain of those conditions said things which were both unwise and untrue when taken literally. Now we have the future before us and it is my hope to see Australia retain her position of advancement in that future. I am sure that, putting aside all partisan feelings on the matter, both you and I desire to see that end attained. You, as representing the Australian government, may differ with me, a private citizen, as to how it is to be done, but I am sure our patriotic motives are the same. I therefore appeal to you, Mr. Hughes, to order that the passport be issued.

I am,

Yours respectfully,

G.E.M. Jauncey

The letter was stamped received in the Prime Minister’s office on 20 July. The underlining in the letter seems to have been done by a pen other than Eric’s, perhaps by an official considering Eric’s case. There is no evidence that Eric received a reply to his letter although his passport was eventually granted by the Bruce-Page Government in 1923. Eric returned (briefly) to Australia in 1926 with his family for a university function in Adelaide. He died in 1947.

A file note from October 1923 [initials illegible] indicates bureaucratic motivations: ‘The Minister [for Home and Territories, Senator Pearce] may consider that Mr. Jauncey has paid a sufficient penalty for his indiscreet & unpatriotic sentiments by being refused permission for six years to return to Australia and may now be prepared to grant the necessary authority. I consider that that would be a reasonable course now to follow.’

This unknown bureaucrat had changed his views from those he held in an earlier note in May 1921 in which he advised the then Acting Minister to refuse Jauncey’s application. ‘This man is clearly dangerous. He loves not America Britain or Aus. He sd he wd never fight for Australia & in regard to his desire to return here he in a letter to a friend sd he “wd be plsd if you wd make a hell of a fuss over this business”. I think we shd let him enjoy U.S.A. a bit longer.’ It seems that, even after the war, Jauncey’s correspondence was still being intercepted.

Source: National Archives of Australia Item A1, 1923/26495, Item barcode 3228095, documents 10-12, 52-58.

Most apropos illustration ….