[Note: This is a translation completed by Professor John A. Moses in November 2017 of a July 2014 review article in German by Professor Heinrich August Winkler on Christopher Clark’s The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914 (Die Schlafwandler: Wie Europa in den Weltkrieg zog). Honest History only briefly noted Professor Clark’s book when it first came out and it thanks Professor Moses for his work on this translation. Professor Winkler’s commentary is particularly interesting for its relevance to German and European politics today. HH]

Heinrich August Winkler (translation John A. Moses)*

‘And deliver us from the war guilt’ (‘Und erlöse uns von der Kriegsschuld’), Die Zeit, 31 July 2014

This book by the Australian historian Christopher Clark on the outbreak of war in 1914 has unleashed a wave of revisionism in Germany.

Germany finds itself moved by the impact of Clark’s book, so much so that one could speak of ‘the Clark effect’. For almost a year this book by an Australian who teaches in England has occupied a place in the bestseller lists. Based on wide-ranging archival studies in eight countries, the book is brilliantly written and illuminates the south-east European pre-history of the First World War. In doing so, it sheds new light not only on Serbian politics prior to the assassination at Sarajevo but also on the active role that Russia and France had been playing on the south-west border of the Habsburg Empire. Central to Clark’s findings is that the crisis of 1914 was extraordinarily complex; he documents this very impressively.

That said, the success of the book in Germany has been for quite different reasons. What Clark writes about Berlin’s policies in the July crisis is imbued to a high degree with a sympathetic understanding, indeed sympathy. The ‘blank cheque’ which the German Empire issued on 6 July – eight days after the murder in Sarajevo of the successor to the throne in Vienna, her partner in the Dual Alliance, namely Austria-Hungary – was, according to the judgement of most historians, a fatal turn on the road which led to the First World War. It enabled the Austro-Hungarian ultimatum to Serbia on 23 July, which resulted in the decisive escalation. Clark, on the other hand, sees in Berlin’s authorisation to Vienna ‘actually no irresponsible risk, but rather a strategy with the objective of sounding out the extent of the threat emanating from Russia’.

That said, the success of the book in Germany has been for quite different reasons. What Clark writes about Berlin’s policies in the July crisis is imbued to a high degree with a sympathetic understanding, indeed sympathy. The ‘blank cheque’ which the German Empire issued on 6 July – eight days after the murder in Sarajevo of the successor to the throne in Vienna, her partner in the Dual Alliance, namely Austria-Hungary – was, according to the judgement of most historians, a fatal turn on the road which led to the First World War. It enabled the Austro-Hungarian ultimatum to Serbia on 23 July, which resulted in the decisive escalation. Clark, on the other hand, sees in Berlin’s authorisation to Vienna ‘actually no irresponsible risk, but rather a strategy with the objective of sounding out the extent of the threat emanating from Russia’.

The subordination of the civilian government in Berlin to the military during the weeks prior to the outbreak of war is denied by Clark though he makes the sweeping generalisation that, ‘In Russia, Germany, Austria, Great Britain and France the military planning took precedence over the political and strategic goals of the civilian leadership’. He implies that the pre-war military system was bogged down in a quagmire from which escape could only be accomplished by a general war. Consequently, the question of who was guilty of the outbreak of war does not arise. Indeed, ‘the crisis which in 1914 led to war was the fruit of a common political culture’.

If Clark is right, then Germany is to a certain extent let off the hook. Admittedly, scarcely anyone advances the thesis of sole German war-guilt any more but, according to the most reliable authors, Germany or the two central powers of Germany and Austria-Hungary bear the main responsibility. Clark sidesteps the war-guilt question by insisting that war was embedded within the logic of the pre-war international system. This explains the overwhelming approval Clark has won within Germany, and only here. Indeed, he has found a predominantly older and conservative upper middle class audience (the Bildungsbürgertum) many of whom have been celebrating Clark as a virtual redeemer (Erlöser). For many, Clark has been welcomed as a liberator from that national ‘self-humiliation’ which Germany assumed some 50 years ago when the theses of the Hamburg historian Fritz Fischer, author of Griff nach der Weltmacht in 1961 (translated as Germany’s Aim in the First World War) became in time the received wisdom among both the professional historians and the general public.

Now Clark’s example has encouraged a number of academic supporters. Among them, Herfried Münkler, a professor of political science in Berlin, has produced in many respects a remarkable book, Der Grosse Krieg. He asserts that, far from being irresponsible or foolhardy, Berlin, by issuing that ‘blank cheque’ to Austria-Hungary, took a calculated risk to head off the possibility of escalating a war. Accordingly, Berlin simply only wanted to give Vienna the possibility of executing a limited military intervention against Serbia in order to prevent a war against Russia with all the expected consequences.

Fritz Fischer (1908-99) (YouTube)

Fritz Fischer (1908-99) (YouTube)

Münkler, grossly misrepresenting Fritz Fischer by accusing him of advancing the thesis of Germany’s sole war-guilt, seeks to portray Fischer as the fabricator of an image of history which needs to be refuted for current political reasons. Münkler argued recently in an interview with the Süddeutsche Zeitung (ironically summarising his views) that, ‘Because we are historically guilty we must not, indeed, may not anywhere pursue an independent foreign policy; rather we should discharge our political responsibilities by becoming only economically involved, acting to stabilise Europe wherever there are crises brewing on the borders’.

As well, a group of three younger historians and a journalist, Dominik Geppert, Sönke Neitzel, Cora Stephan and Thomas Weber, have been encouraged by Clark and Münkler to publish an article in Die Welt, in which they with great satisfaction observe: ‘The war-guilt question which was very high in the German propensity to be self-absorbed (Selbstbezogenheit), a key concept either as a scandal or as self-accusation, has now become irrelevant’. They went on, saying that the First World War was the beginning of many horrors, one of which was the moralisation of war. The multi-polar world of today demanded, more than ever, ‘a realpolitical and not a moral answer to world events’.

In a different way from Münkler, these four commentators in their article in Die Welt link their contribution to the revision of earlier war-guilt theses not with a plea for more foreign policy responsibility but with a rejection of Germany’s international involvement. Indeed, according to them, the popular idea in Germany that a tighter union of the European countries strengthens the cause of peace to the extent that nationalist preoccupations are overcome, rests on a false premise, namely the widespread view among German politicians, in the schools and newspaper offices since the 1960s, that ‘Germany was responsible not only for the Second World War but had also started the First World War’.

Even more curtly, another author, Jörg Friedrich, dismisses the presumed moralists in academia and in the general public by asserting that the ‘guilt question for the First World War belongs in the category of propaganda’. This he presents in his book, 14/18: Der Weg nach Versailles (Berlin: Propyläen Verlag, 2014). In an interview with the magazine Cicero, Friedrich described the German public as being ‘in love with guilt’ (schuldverliebt). ‘But someone may be guilty, say, of a car accident, not for the mutual butchering of millions upon millions of people. So “guilt” is not a historical category. No one asks who is guilty for the Reformation or for the mass migration of peoples. That is a nonsense.’

Christopher Clark (Wikipedia)

Christopher Clark (Wikipedia)

On the question of 1914, the revisionists from Clark to Friedrich are divided among themselves on many things. But what they have in common as far as the pre-history of the First World War is concerned is an old fashioned concentration on diplomatic history, that is, the history of the upper echelon decision-makers among the nations. The question of the political systems and the societies of the then competing Great Powers is virtually neglected. This narrow focus has its drawback: it makes it difficult to assess and compare the war preparedness in each nation.

Of course, in all the participating countries whose armies found themselves at war in 1914 there was a ‘war party’, but in Germany the war party was much more powerful than it was in Great Britain or France. And there were reasons for that which reach far back into the past. Germany was never a parliamentary but rather a constitutional monarchy. This meant that the Reich Chancellor was responsible to the Kaiser and not to the Reichstag. The power of military command (Kommandogewalt) of the King of Prussia – who was also, via the arrangement of ‘personal union’, German Emperor – did not require counter-signing by a Cabinet. Through this provision, a relic of monarchical absolutism had been preserved in the constitutional law and constitutional reality of the Kaiserreich.

‘Great amusement’ over the warning of a world war

The rise of the Social Democrats – who were already since 1890 the strongest single party and, after the national elections in January 1912, the strongest party in the Reichstag – filled the German ruling classes with great anxiety. Many politicians and publicists of the Right considered that a war was the only way permanently to end the danger of a further shift to the Left and a democratisation of the Kaiserreich. For example, in 1911 the paper, Das Deutsche Armeeblatt wrote, ‘For domestic political conditions a generous contest of arms (ein grosszügiger Waffengang) would be a really good solution even if it caused pain and tears for individual families’.

Further, in Die Post, the leading paper of the free conservative Deutsche Reichspartei, one could read on 26 August 1911: ‘In broad political circles there is a very strong conviction that a war could only be advantageous because it would clarify our precarious political situation and lead to a healthier outcome to the many political and social problems’. And when August Bebel, the chairman of the Social Democratic Party, cited these statements on 9 November 1911 in the Reichstag to warn against the catastrophe of a world war, the grosser Kladderadatsch (the great havoc), the parliamentary record (the German Hansard) registered ‘frequent laughter’ and ‘great amusement’ and calls from the Right shouting, ‘After every war things are better’.

Bethmann Hollweg (History Learning Site)

Bethmann Hollweg (History Learning Site)

The Reich Chancellor, Bethmann Hollweg, by no means shared these opinions of the war party. His main fear of a world war was that it would lead to a further strengthening of Social Democracy, indeed to the fall of the monarchy. And so he rejected the contemplation of a preventive war against the powers of the Triple Entente (Russia, France and Great Britain) until the summer of 1914. However, after the assassination at Sarajevo he succumbed to the pressure from the military and did what the war party expected from him: with the ‘blank cheque’ to Austria he consciously accepted the risk, namely, that out of the conflict between Vienna and Belgrade a world war could develop.

A few months after his fall from office, Bethmann Hollweg gave the clue to his turn around, saying to the Reichstag member of the Progressive Peoples Party, Conrad Haussmann, ‘Lord, yes, in a certain sense it was a preventive war. But only if war was hanging over our heads, if it had to come two years later much more dangerously and inevitable, and if the military said today war is still possible without defeat, but no longer in two years. Yes, those generals.’ So here we see the former head of government plagued by doubts and scruples. The question of the war gnawed at him. He asked himself whether it could have been avoided, especially what he, Bethmann Hollweg, could have done differently. ‘All nations are guilty, including Germany, who has a great guilt among the many.’

In contrast to the revisionist historians of today, the Chancellor of 1914 did not, in retrospect, avoid the question of guilt. According to his own witness, he acted in 1914 not as a ‘sleepwalker’ but rather against his own nature and like a gambler making his last throw of the dice (Va-banque Spieler). So, indirectly he allowed that Germany in July 1914 pursued a policy that heightened the crisis and he designated the driving force by name: the military leadership.

Further, in a different way from that in which Clark and Münkler portray it, policy in Germany was determined in the decisive moment by military priorities. Clark’s thesis of a ‘common political culture in Europe in 1914’ accordingly really needs to be corrected. In fact, the decisive German peculiarity has been carefully set out by Jörn Leonhard in his 2014 book, Die Büchse der Pandora (Pandora’s Box), where he observes that in Germany there was a lack of a functioning civil counter weight, an effective monitoring agency over the military. This explains why a vacuum could arise, in which panicky ideas about encirclement and the rapid instinctive commitment to particular modes of reaction could gain the upper hand. This resulted in the policy of 23 July of exerting pressure on Vienna to exploit the situation to put the Serbs in their place and, by doing so, Germany without doubt had incurred a particular responsibility for the July crisis.

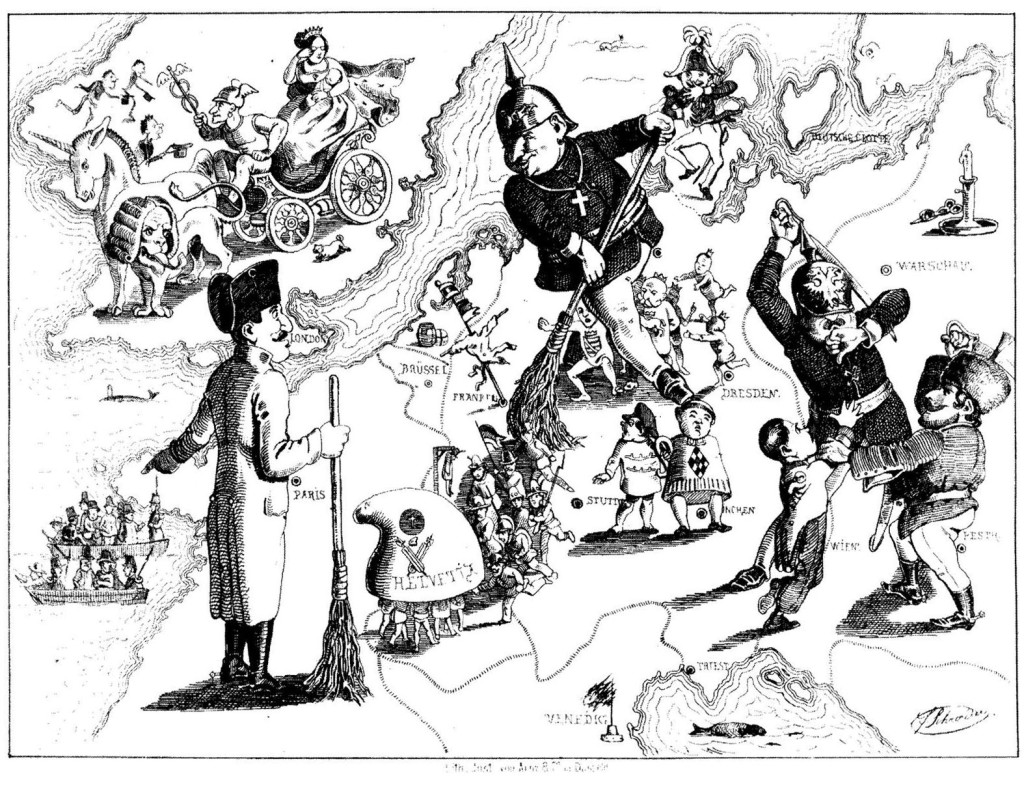

Realpolitik: cartooon depicting the defeat of the 1848 revolutions across Europe; Ferdinand Schröder, Düsseldorfer Monatshefte, August 1849 (Wikimedia Commons)

Realpolitik: cartooon depicting the defeat of the 1848 revolutions across Europe; Ferdinand Schröder, Düsseldorfer Monatshefte, August 1849 (Wikimedia Commons)

Next, the repudiation of moral questions and judgements by some of the younger revisionists recalls strongly the conflict of ideas of previous generations. In the First World War the German ideologists of war opposed the universal morality of the Western democracies with ideas and thinking that derived from the depths of German culture and thereby rejected the norms which were accepted world-wide, namely freedom, equality and brotherhood. Realpolitik, a German concept from the 1850s which has long since become adopted into many other languages, still means in its country of origin only power politics linked with a decisive rejection of the allegedly hypocritical ideals of the West such as human rights and democracy. And it was this mode of thinking which after 1918 the intellectual Right in the Weimar Republic used to advance their ideas of a so-called conservative revolution. It was a movement whose modes of thinking later came to the fore and were also exploited by the National Socialists.

The establishment of the first German democracy, the Weimar Republic, was clearly the result of the defeat in the First World War. It was only towards the end of the war that the moderate elements among the middle classes and the labour movement, represented by the Catholic Centre Party and the left liberal Progressive Peoples Party on the one hand and the Social Democratic Party on the other, finally found a way to collaborate. Without this collaboration, the establishment of a parliamentary democracy in Germany would have been unthinkable. Unfortunately, however, the birth of democracy out of the humiliating defeat was the heaviest handicap on the Weimar state and one of the more profound causes of its failure. Remarkably, in the revisionist writing on the First World War this context is nowhere evaluated.

The result of this mode of thought is that, whoever denies the link between the resistance to democracy among the German elites before 1914 and Germany’s path into the war will be tempted, as was the case of old, to blame ‘Versailles’, the peace treaty of 1919, and to declare it to be the cause of all subsequent ills. So, if Germany is ‘only’ guilty for the Second World War but not for the First World War, one is not far from the claim that Hitler was just an unfortunate political accident (Betriebsunfall) in German history. None of the revisionists up to now has acknowledged this.

That said, however, if it is correct that the ‘Clark effect’ can be explained essentially out of deeply entrenched national apologetic yearnings, then it can be assumed that this conclusion had already been reached by many Germans. Indeed, what the revisionists have contributed to clarifying the current situation is highly questionable. Münkler is right when he warns Germany against any participation in humanitarian interventions and peace-keeping measures, bearing in mind her past. But, on the other hand, to recommend to the Germans in consideration of present day politics a less than self-critical evaluation of their part in the unleashing of the First World War comes close to a re-writing of history with a nationalist pedagogic intention.

Even more concerning are the national and nationalistic tones of the four authors in Die Welt. When they imply that the German advocates of the supra-national unification want a Europe without nations, they echo moods and resentments to which the AfD (Alternative for Germany) and at times the CSU (Christian Social Union) appeal. And the postulate of a historiography ‘without normative ballast’ as one of the authors of the manifesto in Die Welt, Sönke Nietzel, recently in another connection demanded, completely misleads us. The discipline of history underpinned by this directive would take us either into a flat positivism or to that specific German understanding of Realpolitik which contributed to leading Germany into the First World War. It is time for a self-revision of the revisionists.

* Heinrich August Winkler was born in Königsberg in 1938. Since 1991 he has been Professor of History at Humboldt University, Berlin. He is a member of the Social Democratic Party.

Translated by John A. Moses, Canberra, 11-27 November 2017. John Moses is a Professorial Associate of St Mark’s National Theological Centre, Charles Sturt University, Canberra. Among his many publications, he is co-author with George F. Davis of Anzac Day Origins: Canon DJ Garland and Trans-Tasman Commemoration (2013).

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.