‘Great War commemoration in Australia and Britain’, Honest History, 1 September 2014

In Britain they are commemorating the centenary of the First World War. I know this because it says so on my commemorative key chain that I bought at the Imperial War Museum (North) in July. I also know this because the commemorative events staged at the beginning of August were all about the First World War.

In Australia we seem to be commemorating something a little different: a century of ‘Anzac’. Both commemorative events raise the question about the continuities between then and now and whatever lies in between. In other words, is the Anzac we are commemorating in 2014-18 the same as the one that was created in 1914-18? Is there, as Mark McKenna has argued, a sense that we are currently experiencing and celebrating ‘Anzac 2.0’ while we appear to be commemorating ‘Anzac 1.0’?

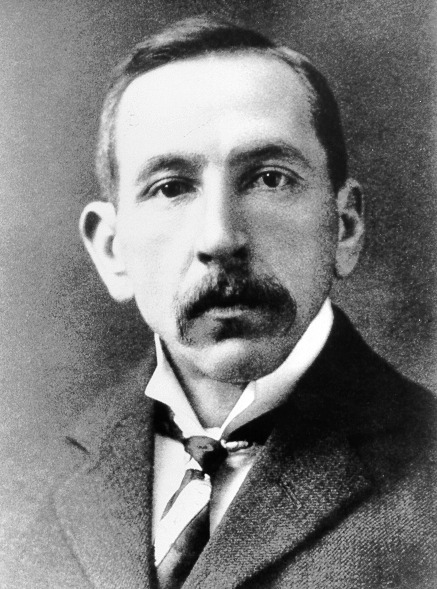

Prime Ministers Abbott and Hughes (Sydney Morning Herald, National Archives of Australia, A1200, 11198546)

The Australian position of commemorating a concept rather than an event may have the virtue of honesty. All commemorative events collapse time and are, via a mixture of existing public knowledge, collective expectations, lobbying and government involvement, inevitably shaped in service of contemporary social concerns and political arguments.

But beneath the swirl of such contemporary activity, there are more persistent concerns and anxieties that commemorative events seek to address. The commemorations of August 2014 appeared to reflect the melancholy of the inter-war period rather than the excitement of the Bank Holiday in August 1914 when war was declared.

British memory is a mix of personal and community loss, tinged with a sense of decline in great power status. The British memory of the First World War (‘lions led by donkeys’) is forced to compete with that of the Second (Britain’s ‘finest hour’). Commemorations of twentieth century conflict in Britain cannot help but incubate a sense of decline, exacerbating questions about the worth of the conflict, picked up by the later war poets, the critics of the 1960s and, of course, Blackadder himself in the 1980s.

For Australia, an opposite trajectory is observable. In 1914, as an imperial great power, ‘Perfidious Albion’ needed no introduction. In contrast, Australia’s dominant need (or anxiety) was for recognition. The Herald Sun’s special pull out section, with its headline ‘Here we come’, and the Victorian Government’s claim to have fired the first shot of the Empire’s war, suggested that need remained.

In 1914, anxieties swirled around national capabilities; could the nation derived primarily from convict stock and with a reputation for iconoclastic innovation prove its manhood on the field of battle? A century later, the national attitude does not have to account for such proto-eugenic notions as the ‘convict stain’ but Australia still pushes to be a middle power ‘punching above its weight’ in international affairs. In 1919 there were 25 governments represented at the peace treaty negotiations. Today Australia is a member of the G20 and chairing the UN Security Council.

There is room in Anzac for a critique of war similar to that to be found in British narratives. However, it tends to get crowded out by the underlying message about the ‘birth of the nation’. This is why it is possible to speak about an ‘Anzac nationalism’ in a way that is harder to isolate in the British case. And it suggests that, just as Anzac emerged as a powerful narrative of nationhood in the 1915-19 period and after, it might be performing the same function today, although in a radically different globalised and geopolitical context.

Of course, both Britain and Australia will need these commemorative narratives to re-establish a narrative continuity that may have been sundered by the regime change of globalisation from the 1970s to the 1990s and beyond. For British commemorations this again suggests negotiating some painful memories of loss and diminishment for event planners and commentators, making the commemorations relevant to a multicultural and diverse audience, and not offending partners within the European Union or even those within the United Kingdom.

Poppies at the Tower of London, August 2014 (Flickr Commons/Henry Bloomfield)

For planners in Australia the nation-building context allows for a set of more upbeat conclusions. Since the point of rupture in the 1970s Australia has sought a different position in global affairs and one that it has by-and-large succeeded in attaining. Although the difficulties of speaking to a diverse audience are present, the Great War can be portrayed as Australia’s entry into world affairs and the beginning of the story about Australia’s rise as a middle power. It also allows for the difficulty of divers audiences to be addressed: Anzac as a form of Australian kinship can speak to those Australians whose forebears have been here for many generations; as a set of values it can transcend kinship and (potentially) speak to those whose forebears are of more recent provenance on these shores. Yet how successfully commemorative planners can do this remains to be seen, especially in regard to Indigenous Australia.

British commemorations are at pains to include Commonwealth partners. (‘Commonwealth’ in this regard can be read as a synonym for multicultural Britain today as well as re-energised links with Commonwealth countries; the UK’s links with the EU become ever more complicated.) For Australia, the commemorations give us the chance to re-work Billy Hughes’s diplomacy for global times and assert that ‘Australia will be there’ once again.

Ben Wellings is Lecturer in European Studies at the Monash University European and EU Centre, Melbourne. He is the author of English Nationalism and Euroscepticism: Losing the Peace (Peter Lang, Oxford, 2012) as well as articles on English nationalism. He is co-editor with Shanti Sumartojo of Nation, Memory and Great War Commemoration: Mobilizing the Past in Europe, Australia and New Zealand (Peter Lang, Oxford, 2014).

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.