In 2015, the late Professor Stuart Macintyre published a great book on Post-War Reconstruction, describing the work of politicians and bureaucrats in Australia during and after the Second World War. Australia’s Boldest Experiment: War and Reconstruction in the 1940s won the inaugural Ernest Scott Prize. Honest History’s review note of the book is reproduced below. Obituaries for Professor Macintyre.

‘Review note: Stuart Macintyre’s Australia’s Boldest Experiment‘, Honest History, 19 August 2015 updated

World War I is far enough back for spruikers of a particular view of it to extract bits selectively from, say, the ambivalent Charles Bean and impress lunchtime audiences. The diners will be ‘moved’ and will not suspect that they have been served up with their dessert what a colleague of this reviewer has described as ‘marshmallow history’. Perhaps they don’t care; being moved possibly helps the digestion.

Not enough of us know enough about the Great War. Far from rising, in the words of the inevitable Bean, ‘above the mists of ages’, that war is sinking beneath clouds of sentimental fog. World War II is different. Us baby-boomers came onto the scene just after it. This reviewer can still be moved to tears by a recording of Chifley’s announcement of the end of the war in August 1945, an event that occurred just four years before I was born – recent enough for it to directly mean a lot to my family. Our parents and our teachers carried the scars of that war, our Generation Y children have sat on the knees of men and women who suffered in it; it is much more ‘our war’ than that earlier one a century ago, despite how the Anzac centenary industry, for its own purposes, likes to pump up the first big show.

Not enough of us know enough about the Great War. Far from rising, in the words of the inevitable Bean, ‘above the mists of ages’, that war is sinking beneath clouds of sentimental fog. World War II is different. Us baby-boomers came onto the scene just after it. This reviewer can still be moved to tears by a recording of Chifley’s announcement of the end of the war in August 1945, an event that occurred just four years before I was born – recent enough for it to directly mean a lot to my family. Our parents and our teachers carried the scars of that war, our Generation Y children have sat on the knees of men and women who suffered in it; it is much more ‘our war’ than that earlier one a century ago, despite how the Anzac centenary industry, for its own purposes, likes to pump up the first big show.

Stuart Macintyre was born in 1947 and his Australia’s Boldest Experiment: War and Reconstruction in the 1940s is an anthem to the time of Curtin and Chifley, Crawford and Coombs, Calwell and Copland, Burton, Dedman, Evatt (and Menzies) and all of the others who plotted and planned for a different Australia after that war. Macintyre disposes of the Anzac commemoration industry in the book – a while ago he referred Honest History to the term ‘Anzackery’ to describe the overblown, jingoistic end of that industry – with this pithy paragraph, scooping up sloppy portrayals of the second war, too:

More recently, the Pacific War has been recast as an epic struggle against an imminent threat of invasion, and the engagements in Papua New Guinea and its surrounds have been gathered into a “Battle for Australia” that has been commemorated since 2008 on the first Wednesday in September. This freshly minted event is part of an upsurge in war remembrance served by new monuments, augmented anniversaries and contrived discoveries … Such war history has assumed mythical status. Just as the story of Gallipoli drew on Homer’s epic story of the siege of Troy, so that of Kokoda has taken on the legendary proportions of the battle of Thermopylae, where a band of Spartan warriors sacrificed their lives to prevent conquest by a vast imperial army.

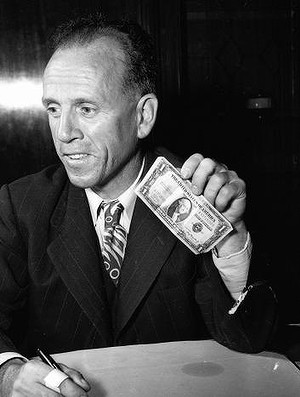

Macintyre’s war and its aftermath does not fit those easy templates. Indeed, in some ways, it seems a long way from Kokoda. The book is ‘inside out’ from the perspective of the close advisers to Curtin and Chifley. It is brilliant administrative history, getting us into the committee rooms and the telephone calls, the drafts and redrafts (for example, of the full employment White Paper), the long train journeys from Melbourne to Canberra (or Perth to Canberra, if you were Curtin). The many-layered ‘Nugget’ Coombs – one reviewer calls him ‘superhuman’ and he is without doubt the real hero of the book, the anguished Trevor Swan, the fastidious Paul Hasluck, the avuncular Lyndhurst Giblin, perched in West Block amidst pipe smoke, the rare women, like Flora Eldershaw, the urbane Douglas Copland, trying to cultivate Menzies in opposition, all play their part. Some of them may have had a better grasp on post-war community priorities than did others. All of them ‘served’ as much as did men and women in uniform. And they did have to help win the war as well as work out what to do after it.

Documents from the archives are merged smoothly into Macintyre’s narrative; those of us who researched this era 40 years ago – without access to this material – are still envious. Canberra in wartime is not as interesting as Civil War Washington (as presented in, say, Margaret Leech’s Reveille in Washington 1860-1865 – we don’t get President Lincoln and Mary Todd riding out in the buggy in the afternoon but we get Curtin and Chifley strolling in from the Hotel Kurrajong) but Macintyre makes it a damn fascinating place. A few more glimpses of life in the sleepy, browned-out streets of Kingston and Forrest would have made it even more interesting. On the other hand, these officials seem to have worked so hard that they may rarely have got home to their shared houses and government hostels.

An ‘inside, looking out’ tale from the politicians’ perspective, rather than the public servants’, would have given more weight to the former’s fears (on behalf of the people) of a new depression descending after the surrender of Japan. (This fear, I am sure, was a central cause for Chifley’s punt at bank nationalisation.) But the boundaries had to be drawn somewhere and this is, taken altogether, an eminently satisfying book.

HC Coombs, 1951 (Sydney Morning Herald)

HC Coombs, 1951 (Sydney Morning Herald)

‘Macintyre reminds us’, says NewSouth’s blurbster, ‘that key components of the society we take for granted – work, welfare, health, education, immigration, housing – are not the result of military endeavour but policy, planning, politics and popular resolve’. The chapter titles are ‘The distant war’, ‘Anticipation and procrastination’, ‘The enemy at the gates’, ‘The Ministry of Post-War Reconstruction’, ‘Food and shelter, family and community’, ‘Welfare’, ‘The positive approach’, ‘Final preparations’, ‘Demobilisation’, ‘Chill winds’, ‘Catching up’, ‘End of an era’.

Stuart Macintyre is one of Honest History’s distinguished supporters and we are pleased at that. Everyone should read this book – particularly those who have tended to go in for marshmallow history as spruikers or consumers. The book has also been considered by Hannah Forsyth (review in Inside Story), the author and Mark Colvin on PM, Ross Fitzgerald in The Australian, Beverley Kingston in Fairfax, and the author and Geraldine Doogue on Saturday Extra. Finally, a guide has been published to the National Archives resources used to write the book. And out the back and a little bit to the side, an ABC item about an inconspicuous brick building behind West Block that sent cables to Winston Churchill during the war.

***

28 November 2021

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.