‘Out of the great Australian silence: Frank Byrne’s Stolen Generations story’, Honest History, 22 November 2018

David Stephens reviews Living in Hope, by Frank Byrne with Frances Coughlan and Gerard Waterford. The book is the winner of the Small Press Network award for the Most Underrated Book 2018. Frank Byrne died on 20 October 2017. Warning for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples: this content contains images and/or voices of deceased persons.

Fifty years ago, the anthropologist WEH Stanner wrote about ‘the great Australian silence’, the inability of Anglo-Celtic and other non-Indigenous Australians to confront what had happened to their Indigenous fellow Australians since 1788. Stanner’s aphorism reminds us yet again that history is as much about forgetting as it is about remembering.

Fifty years ago, the anthropologist WEH Stanner wrote about ‘the great Australian silence’, the inability of Anglo-Celtic and other non-Indigenous Australians to confront what had happened to their Indigenous fellow Australians since 1788. Stanner’s aphorism reminds us yet again that history is as much about forgetting as it is about remembering.

To reverse that balance – to make remembering less painful – depends partly on our getting our head around Indigenous stories, often passed down through generations. Just because these stories do not feature in collections of ‘whitefella evidence’, written records and official paperwork, does not mean they are less worthy of note.

Frank Byrne’s story starts in the Kimberley region of Western Australia, as recently as 1937, when he was born on Christmas Creek station, the son of Maudie Yoorungul, a Gooniyandi woman, and Jack Byrne, an Irish stockman. Frank’s mother called him Goondarie; his stepfather was Jumargoo Lembing, a Walmatjarri man.

This 54-page book, written with the help of Alice Springs social workers, Frances Coughlan and Gerard Waterford, tells us about Frank’s life to the age of 15 years. It is the first in the Inland Writers Series, published by Ptilotus Press, Alice Springs. The book is nicely produced, with a facsimile of the author’s handwriting on the inside covers.

Byrne writes of an idyllic early childhood at Christmas Creek and visiting his stepfather’s country, then of being taken at the age of six years from his family – against his and their will but in accordance with government policy for ‘half-caste’ children – and being sent to the primitive Moola Bulla settlement. (He did not know his Anglo name until he heard it called at roll-call, before he was turned out into a paddock ‘like a poddy calf’.) He then moved to the rather better conditions at the Beagle Bay mission school, where nuns and priests delivered food, a basic education, and the rudiments of Catholic faith.

The young Frank did not see his mother after he was about seven – he found out some years later she had died – and did not see his stepfather from two years after that. When he ‘graduated’ from Beagle Bay, he went to work with his natural father, whom he had never previously met.

The facts are brutal enough and simply told; additional power resides in the occasional searing paragraph.

The killing times were barely over in the Kimberley and Aboriginal people were still being terrorised by whitefellas. What I knew, even as a small boy, was that no-one argued with a whitefella. People talked in whispers when whitefellas were present. (p. 8)

When the men from the department arrived to take the children away, ‘I think I went mad. I wanted my mother and I cried, but they would not let me go. They just held me there till the truck went out of sight.’ (p. 12)

Frank was sustained by mob, common language, and his special companionship with Frieda Wilson, another Beagle Bay ‘half-caste’:

We lost the love of our mothers and we search for comfort in every relationship for the rest of our lives. For a little bit of time when we were little kids, Frieda and me did that for each other and I still remember that comfort today. (p. 25)

There is also a telling comparison with ‘the fallen’ in other battles, which comes when Byrne lists the names and place of residence of survivors from his Stolen Generations group. ‘It’s like a roll call of people who went to war together. It’s a roll call of us stolen kids who survived together.’ (p. 30) This is crying for those who are gone, holding close those who remain. ‘Lest We Forget’ need not have a khaki tinge.

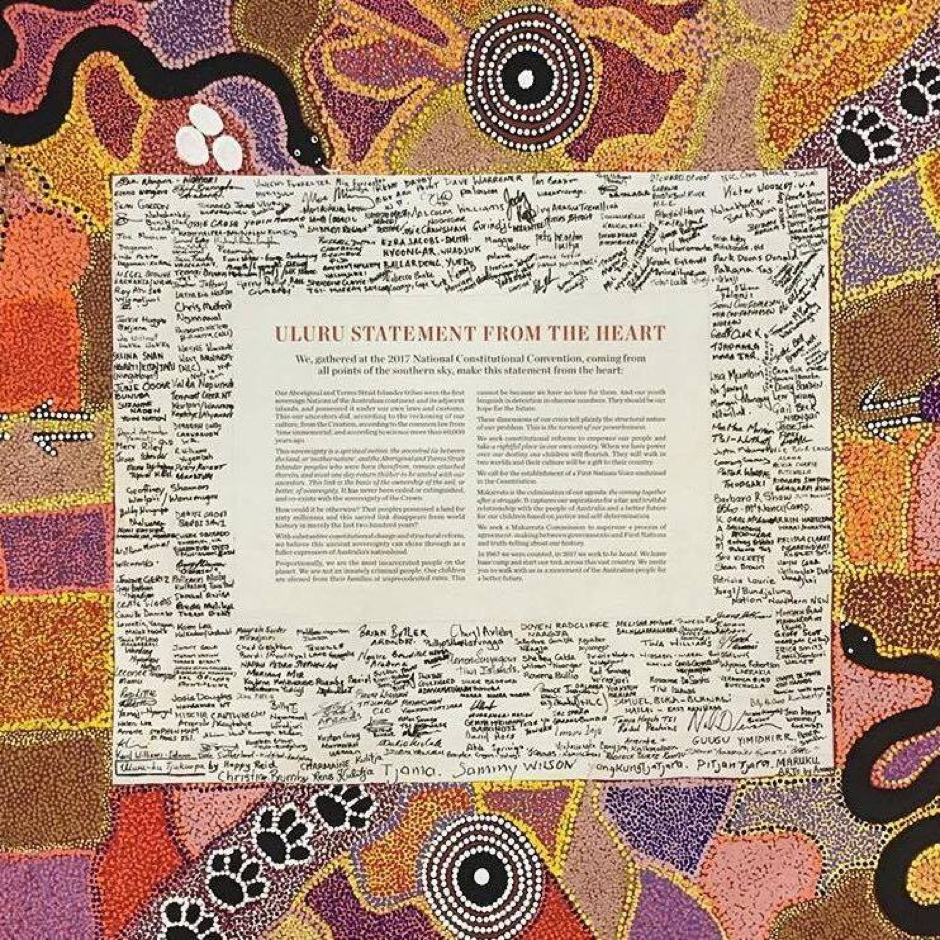

Uluru Statement with signatures (1VoiceUluru)

Uluru Statement with signatures (1VoiceUluru)

Yet the book is not primarily about massacres and poison waterholes, but resilience and survival. And that is good. Once we get used to knowing and remembering and admitting and thinking about our country – in all its nuances and all its rawness – healing may (gradually) follow.

Frank Byrne’s little book, like the Uluru Statement from the Heart, Makarrata, and the hard-won successes of Indigenous role models, should help make us more aware of what a thoughtful whitefella, Mark McKenna, in his recent Quarterly Essay called ‘the central drama of Australian history: the encounter between Aboriginal people and the strangers who came across the seas to claim their lands’. If that awareness does not happen, we do not deserve to keep this country.

* David Stephens is editor of the Honest History website and co-editor of The Honest History Book (NewSouth 2017). He reviewed Growing Up Aboriginal in Australia, edited by Anita Heiss, and has written many other articles for Honest History (use our Search engine).

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.