‘This book about growing up Aboriginal in Australia is not just one for whitefellers of a certain age’, Honest History, 20 April 2018

David Stephens reviews Growing Up Aboriginal in Australia, edited by Anita Heiss

It makes a lot of sense that this review is being done by a whitefeller born in 1949. Australia is still disproportionately under the influence of Anglo-Celtic blokes born in the years between 1945 and say, 1970, the years of the baby-boom and the decade or so after. It is the attitudes and prejudices of men of this age group that still have more influence than they deserve – and that needs to change.

Our – baby-boomer whitefellers’ – childhoods and teenage years formed these attitudes and prejudices, including our attitudes to and prejudices about Aboriginal Australians. Consider that, as children and youths, we routinely used words like ‘Abo’, ‘boong’ and ‘coon’, even though most of us in the suburbs had never met an Aboriginal Australian. We have spent our adult years working on getting our heads shifted, but it has not been easy.

Our – baby-boomer whitefellers’ – childhoods and teenage years formed these attitudes and prejudices, including our attitudes to and prejudices about Aboriginal Australians. Consider that, as children and youths, we routinely used words like ‘Abo’, ‘boong’ and ‘coon’, even though most of us in the suburbs had never met an Aboriginal Australian. We have spent our adult years working on getting our heads shifted, but it has not been easy.

We – those young Anglo-Celtic ‘Lords of Creation’ – accepted that Aboriginal Australians needed to be treated with paternalistic care if they were to be helped to ‘assimilate’ into white society. We concluded, if Aboriginals backslid, that it was ‘the way they live’. We accepted – when we asked our parents ‘what happened to all the Aborigines?’ – the answer that ‘they died out’. We saw nothing odd in history textbooks that told us the Australian story began in 1770 with the arrival of Captain Cook. We read about Truganini, the Last Tasmanian, and felt a little sad for a moment. That was the way it was in the Australia where bright, white Peters’ Ice Cream was ‘the health food of a nation’.

Now, Wiradjuri woman Anita Heiss, editor of this collection, tells readers that each of the fifty or so pieces (more than half by women) ‘reveals to some degree, the impacts of invasion and colonisation – on language, on country, on ways of life, on how people are treated daily in the community, the education system, the workplace and in friendship groups’. The diverse stories come from all over what is now called Australia but is still the country of the Noongar, the Wurundjeri, the Wiradjuri, the Arrernte, and the Wakka Wakka, ‘sometimes calling for empathy, oftentimes challenging stereotypes, always demanding respect’.

But the stories are mostly not about laying blame. It will be difficult for Anglo-Celtic readers of these stories to dismiss them by saying, ‘not our fault, it was a long time ago’. Heiss’s authors imply ‘that is not really the point, whitefellers’. Instead, the point is helping us ‘learn about what it means to grow up as a First Nations person in a country where they are often viewed and treated as second-class citizens, and sometimes even worse than that’. Yet, the anthology also presents ‘strength and resilience … pride and inspiration [and] strong communities, with a generous heart and passion for change’.

The stories come from quite well-known people like writers Tony Birch and Jack Latimore, journalists Celeste Liddle and Amy McQuire, singer Deborah Cheetham, footballer Adam Goodes, athlete Patrick Johnson, and actor Miranda Tapsell, but also from ‘ordinary folk’ selected from the 120 contributions received. It is difficult to pick favourite contributors from such a large field but the recurring themes hit this reader hard. Within each theme, there are diverse individual experiences.

First, there is the importance of family, even when family arrangements are unconventional (by Anglo-Celtic standards) and family members are separated by distance, sometimes for long periods, or permanently, due to broken relationships. Story after story in the book attests to the resilience of family links, even in poverty or battlerdom, and how family builds resilience. And, not far beyond family, are elders, who mentor young people like Bundjalung-Gumbaynggirr man Todd Phillips.

Secondly, there is the importance placed on kinship ties and affinity with country – and on Aboriginality itself. ‘I was a descendant of the valley’s first people’, writes Jack Latimore. ‘The oldest stories of the rivers, lakes and mountains were an integral part of me, and I felt I was an integral part of them.’ ‘Land holds stories’, writes Darumbal-South Sea Islander woman Amy McQuire, ‘and within those it contains the people both of the past and the present’. Kamilaroi-Dunghutti woman Marlee Silva returns to country where ‘nobody cares what colour I am. They care only about who I am.’

Thirdly, there is the obsession (hinted at by Silva’s remark) of non-Indigenous Australians with ‘how Aboriginal’ a person is: ‘One-eighth? One-quarter? Half?’ And how they look, with the references to the shade of skin colour: ‘you’re not black enough to be Aboriginal!’

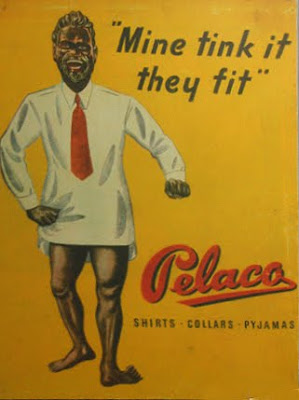

One of a series of advertisements from the 1940s (Loonpond)

One of a series of advertisements from the 1940s (Loonpond)

Having a lighter skin tone, I have been told by others, both Koori and non-Indigenous, [writes Gunditjmara-Kirrae Whurrong woman Alicia Bates] that I am “too white to be Aboriginal” and that I have “more white blood than black blood”. Last I checked, my blood was red just like everybody else’s, and I’m not sure when exactly or how these people measured how much “black” was in my blood.

Some of the authors admit to past sensitivity about how they look, worrying about their friends’ comments about their ‘Abo nose’ or their dark skin; others make the sensible point that identity is not about skin shade. ‘I didn’t know’, recalls Yorta Yorta-Dja Dja Wurrong man Zachary Penrith-Puchalski, of his seven-year-old self, ‘that people would define me as “not looking that Aboriginal”, as if it were a compliment’. Regardless of colour, Jerrinja woman Shahni Wellington and others tell of questioning their identity, under pressure from family, friends, teachers and others.

Menang-Gnudju woman Carol Pettersen, now in her late seventies, remembered a mission childhood in Western Australia:

[O]ur father was white and our mother was black, and we had four shades of skin colour in our family. The mission people, following government requirements, had to segregate us into separate castes, based on the colour of our skins … When [our father] applied to get married to my mother, he had to sign a “contract” to ensure that his wife and family would live as “whites”, otherwise their marriage would be revoked and his children taken away again.

Fourthly, quietly but always there, there is recognition of historic dispossession and its implications. D’harawal woman Shannon Foster notes that history taught to her began at 1788 – but she knows about the sesquicentary protests of 1938. There are Stolen Generation survivors and descendants, experiences of assimilation policies, here and there political activity. There is anger but there is also resignation and fatalism. Some of the authors tell of responding to abuse, verbal and worse; others dealt with it in different ways, sometimes by hiding their Aboriginality.

Some authors mention racial slurs, though no author that I could find speculated whether slurs from non-Indigenous Australians were a way of dehumanising Aboriginals, and thus reducing the importance of the ill-treatment they had suffered. ‘Casual racism is at the root of the divide between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians’, writes Shahni Wellington. One wonders if it is casual because it is not the Anglo-Celtic Australian way to put effort into anything, or because the power imbalance between Aboriginals and non-Aboriginals means that the latter see no threat from the former – and so casual racism is sufficient.

Finally, there are pithy summings-up of what it has meant to be Aboriginal in 20th and early 21st century Australia. The theme here is the understanding of the situation, the instinctive grasping – because it has been front of mind for generations – compared with what seems to the authors in the book (and to me as a whitefeller) the lack of understanding and empathy of most Anglo-Celtic Australians and most immigrants.

And there is simple, powerful prose, as well.

I learnt [writes Sharon Kingaby, born 1960] what these – my – people have gone through since colonisation, from massacres to removals. I learnt what we’re still going through, from institutionalised to casual racism. I learnt that our people are generous and big-hearted, proud and loud, and funny and loving. And I learnt that we still, fifty years later, face so many of the same things that little seven-year-old girl hid from.

Celeste Liddle (Guardian Australia)

If I am honest: [says Arrernte woman Celeste Liddle] as I push the boundaries of my thirties and head into my inevitable forties, I still feel like I am “growing up Aboriginal”. On a daily basis, I am still fighting those exact same racist struggles that I faced as a kid with a cultural background deemed “undesirable” by others.

I started this review with middle-aged to elderly whitefellers. I think this book should ring lots of bells for those blokes, but it is not just for them. (Students growing up in Australia today will cotton on to it.) All of us absorbing these stories of growing up Aboriginal is part of all of us relating to a complex future Australia, where the Anglo-Celtic paradigm is reduced in importance, and Indigenous and non-Anglo Celtic immigrants fill the space. And we – all of us – will imagine our past differently.

Indigenous stories are particularly important in this reimagining: the Australians who carry those stories link us back to ‘Deep Time’, a new but old bedrock. Historian Billy Griffiths, in his book Deep Time Dreaming, quotes Arrernte-Irish-Kalkadoon man, Charles Perkins, a distinguished public servant, explaining his ‘expectation of a good Australia’, which is, Perkins said, ‘when White people would be proud to speak an Aboriginal language, when they realise that Aboriginal culture and all that goes with it … is all part of their heritage … [A]ll they have to do is reach out and ask for it.’ This book helps get us – old whitefellers and the rest of us – to that point.

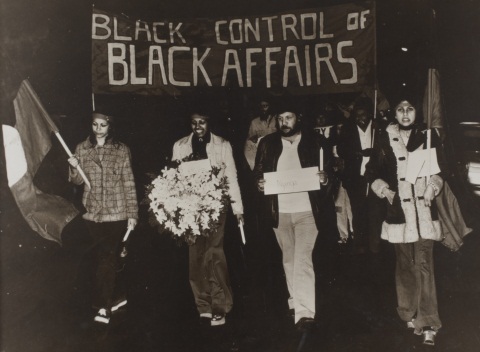

Protest c. 1970s (NMA/ATSIC)

Protest c. 1970s (NMA/ATSIC)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.