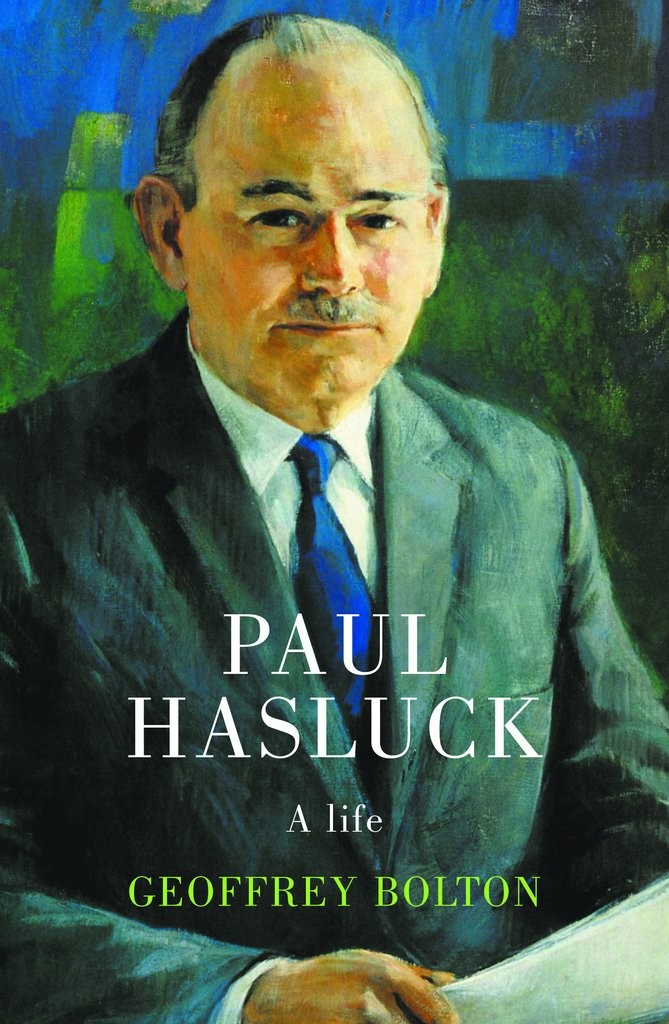

‘Review notes: Geoffrey Bolton on Paul Hasluck’, Honest History, 11 January 2017

This book (Paul Hasluck: A Life) was published in 2014 and its author, Emeritus Professor Geoffrey Bolton, has since died. The book deserves recognition after this lapse of time for three main reasons: first, it is a model of how to write a traditional ‘life and times’ biography about, secondly, a not particularly attractive subject, and, thirdly, it highlights that there is an Australia outside SydMelCan, an Australia which has its own style and imperatives.

The model book is built around ‘Part I: Years of aspiration, 1905-51’ and ‘Part II: Years of authority, 1951-93’. We run from chapter 1, ‘Beginnings’, to chapter 23, ‘A vigorous retirement’, with only a short concluding chapter, ‘An intellectual in politics’. Bolton takes us through Hasluck’s childhood in Western Australia as the son of a Salvation Army family (his father was baptised ‘Ethel’ though Bolton explains this away), through journalism in Perth, significant roles in the wartime Department of External Affairs and in Indigenous affairs, authoring a volume of the official history of Australia in World War II, into politics in the Menzies election of 1949, then 13 years as territories minister (dealing particularly with Papua New Guinea and the Northern Territory), then five years as Minister for External Affairs (Confrontation and Vietnam) and five as Governor-General, before retiring at 69 and pottering about in retirement.

The model book is built around ‘Part I: Years of aspiration, 1905-51’ and ‘Part II: Years of authority, 1951-93’. We run from chapter 1, ‘Beginnings’, to chapter 23, ‘A vigorous retirement’, with only a short concluding chapter, ‘An intellectual in politics’. Bolton takes us through Hasluck’s childhood in Western Australia as the son of a Salvation Army family (his father was baptised ‘Ethel’ though Bolton explains this away), through journalism in Perth, significant roles in the wartime Department of External Affairs and in Indigenous affairs, authoring a volume of the official history of Australia in World War II, into politics in the Menzies election of 1949, then 13 years as territories minister (dealing particularly with Papua New Guinea and the Northern Territory), then five years as Minister for External Affairs (Confrontation and Vietnam) and five as Governor-General, before retiring at 69 and pottering about in retirement.

Bolton’s research (over many years, including archival material) was meticulous, he interviewed a number of people who knew Hasluck, including senior politicians, Hasluck’s longtime secretary, and members of his family. At the end, one feels that there could not be more to be said about Paul Meernaa Caedwalla Hasluck (except possibly about his relations with his occasionally fractious wife Alix – he gave her cause, though, with his prioritising of work over family).

And yet – and here we come to the second point – despite Bolton’s thoroughness and deliberation and his bending-over backwards to be fair, it is very difficult to like Hasluck. Norman Abjorensen has told the story of how he decided not to do a biography of Alfred Deakin because, having got into the subject, he found he could not bring himself to like ‘Devious Deakin’. Bolton, one feels, did come to like Hasluck for his devotion to duty, his intellectual output – though to call him ‘an intellectual’ is perhaps a stretch, more of a disciplined thinker who produced a number of pathbreaking works – and his busyness, but the reader may find it more difficult to get to the same place as the author. There is something about Hasluck’s precise little moustache, the way he took offence at slights, his ability to pick and stick at fights, that suggest he would have been an uncomfortable companion on those long flights from Perth – and in other situations as well. Hasluck complains a number of times about feeling out of place in his various jobs and we can only wonder whether, if he had come to particularly the External Affairs job a few years earlier, he might have been less grumpy.

Hasluck might have become prime minister had he pushed harder after the death of Holt, but probably would not have enjoyed the gig. Still, his grasp of detail in his portfolios and as Governor-General seems to have been formidable and one can imagine public servants preparing very thoroughly for sessions with him. And thoroughness on both sides of the political advice game is no bad thing.

Thirdly, the view of and from Perth. Western Australia is still a different and far country, even today, and it would have been much more so in the 1930s – a majority of them wanted to secede, for heaven’s sake – or even the 1940s, when most travel to the rest of Australia was still by ship or train. Bolton, a true-blue Westralian, gives a good account of Hasluck the loyal son of Perth and district, premier ticketholder of the Claremont Tigers (whose club song, it should be noted, is pinched from the Richmond club in Victoria), isolated for long periods from family and friends by duties ‘over East’. Perhaps part of Bolton’s empathy with Hasluck arises from their shared ‘Perthiness’.

As for the book, UWAP did a nice job packaging it, but for one or two typoes and a rather clanging error in the captioning of one of the photographs. The smiling, bespectacled chap with Hasluck and Bert Evatt at a United Nations pow-wow in London in 1946 is certainly not Australian High Commissioner, ‘Stabber Jack’ Beasley. Research by my co-author shows that the gent in question is one David Owen, a British delegate (not the 1970s politician of the same name). The odd thing is that the man is correctly identified in Hasluck’s posthumous The Light that Time has Made (1995), p. 127. Bolton’s error is minor but it would have irritated PMC Hasluck.

Geoffrey Bolton’s biography of Hasluck was a long time in gestation. In 2003 Bolton was awarded the Frederick Watson Fellowship by the National Archives of Australia for ‘a study of Paul Hasluck and his influence on indigenous affairs and foreign policy’. This is likely to have been the starting point for the project.

Geoffrey Bolton (Perth Now)

Geoffrey Bolton (Perth Now)

There were many sides to Hasluck’s public life and for this reason researching and writing a major biography of Hasluck would always be a protracted exercise. With the biographer’s access to the Hasluck collection of family papers, and a wide range of archival and published material, the final work provides a valuable narrative of Paul Hasluck’s public life that extended from employment as a journalist (appointed to the West Australian in 1923); early exposure to Aboriginal cultural and policy issues; appointment to the diplomatic service; and a political career with election to Parliament in 1949 and service as a minister from 1951 to 1969, at which time he was appointed Governor-General.

One of the great advantages for a biographer of Paul Hasluck was the subject’s passion for history and writing. He was a productive author: Bolton’s biography lists fifteen books written by Hasluck, ten of which are biographical or significant historical works, including two of the volumes of the Official History of Australia in the War of 1939-1945. One of the most interesting, even controversial, of Hasluck’s books was The Chance of Politics, a selection of pen-portraits of political figures of his era.[1] This work was published posthumously, edited by Hasluck’s son, Nicholas. It is curious that Geoffrey Bolton as biographer chose not to pay close attention to or draw conclusions from these frank assessments of Hasluck’s close political associates.

Jim Davidson’s biography of the historian W K (Keith) Hancock noted the comment of the South African historian TRH Davenport that Hancock’s biography of Jan Smuts, published in two volumes in 1962 and 1968, was ‘an old man’s book about an old man’[2]. How does this cruel, even cynical, assessment of Keith Hancock’s work measure up as a standard for Geoffrey Bolton’s Paul Hasluck biography that was commenced in 2003 and published in 2014, a year before Bolton’s death at the age of 83? Neither the duration of the research project nor the age of the biographer should detract from the value of Bolton’s enterprise. We are fortunate that the final work of an historian of great distinction should be the definitive biography of one of the most significant Australian figures of the 20th century.

Apart from contributing his Online Gems to Honest History, John Myrtle has reviewed a number of books for us, Stephen Dando-Collins’ biography of the author Paul Brickhill, Graham Seal’s Great Australian Journeys, and Avan Judd Stallard’s Antipodes: In Search of the Southern Continent.

[1] The Chance of Politics (ed. Nicholas Hasluck), Text Publishing, Melbourne, 1997, 184. Hasluck on William (Billy) McMahon: ‘The longer one is associated with him the deeper the contempt for him grows and I find it hard to allow him any merit. Disloyal, devious, dishonest …’

[2] Quoted in Jim Davidson, A Three-Cornered Life: The Historian W K Hancock, UNSW Press, Sydney, p. 369.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.