‘How does the tax-paying record of large Australian companies square with our much-vaunted Australian egalitarian ethos?’ Honest History, 18 February 2018 updated

The ABC’s chief economics correspondent, Emma Alberici, this week put out some articles on the tax paid by some Australian companies.

There is no compelling evidence [said Ms Alberici] that giving the country’s biggest companies a tax cut sees that money passed on to workers in the form of higher wages … It’s also disingenuous to talk about a 30 per cent rate when so few companies pay anything like that thanks to tax legislation that allows them to avoid paying corporate tax. Exclusive analysis released by ABC today reveals one in five of Australia’s top companies has paid zero tax for the past three years … The overwhelming benefit of higher profits flows to shareholders.

The ABC is reviewing some of the content of one article (original version of the article) and has made some revisions to the other article (here). Revision of the original article.

In the same ball-park as Ms Alberici, though, the Australian Taxation Office said in December that 732 companies paid no tax in Australia in 2015-16. (Last week’s media release from the ATO.) The US Congressional Budget Office reckons Australia’s effective corporate tax rate is not 30 per cent but 10.4 per cent, one of the lowest in the world. Jim Killaly, former ATO senior official, has written at length about international tax shifting arrangements.

Ms Alberici’s work earned her a serve from the prime minister, who said hers was ‘one of the most confused and poorly researched articles I’ve seen on this topic’, because it misunderstood the roles of investment and risk in a capitalist system. (Others disagreed: Greg Jericho in Guardian Australia.) In November, the prime minister had said that the Royal Commission on banking ‘will not put capitalism on trial’. The corporate tax system, like the banking system, is a pillar of capitalism. However, we need to consider how a tax system that allows outcomes like those Ms Alberici described or the ATO identified – or a banking system that delivers massive profits to shareholders while letting customers down – squares with Australia’s egalitarian ethos.

The prime minister often enthuses about egalitarianism. As he said on Australia Day 2017,

here under the Southern Cross we have forged our own nation with unique Australian values – democratic and egalitarian. Deep in our DNA we know that everyone is entitled to a fair go in the great race of life. And that if you fall behind, we are happy to lend a helping hand to get ahead. This strong sense of justice springs from the solidarity, the mutual respect, the mateship that transcends and binds us together in our diversity.

And that is always when we are at our best and most Australian – the selfless sacrifice of the diggers a century ago, the courage of their descendants in the Middle East today. Volunteers fighting fires and floods, pulling kids out of a rip at the beach, rushing to the aid of the wounded on Bourke Street.

But companies paying minimal or no corporate tax (because they fail to make – or contrive not to make – the profits on which this tax is levied) contribute to inequality – and deny the egalitarian ethos – just as surely as do poverty-line social security payments, casualisation of employment, being Indigenous, remote areas’ lack of access to services, corporate boards paying massive bonuses to executives, shareholders reaping dividends while workers’ wages stagnate in real terms, rich families passing on assets from generation to generation, or any of the many other drivers of inequality. Gaming the tax system means there is less taxation revenue to spend on services for the benefit of all of us, particularly those who need these services most.

Over recent years Honest History has collected lots of resources on inequality and its causal factors. One of the themes of The Honest History Book, too, was the disparity between the Australian egalitarian ethos and our unequal reality. In her chapter in the book, academic and former politician, Carmen Lawrence, said this:

Today, the wealthiest 20 per cent of Australians own 61 per cent of the nation’s wealth, the poorest 20 per cent just one per cent. Although the income disparities are less marked, they too have been increasing. OECD data show that the richest ten per cent of Australians captured almost 50 per cent of the growth in gross domestic product (GDP) over the last three decades. A significant minority of citizens live in outright poverty, this figure being estimated by ACOSS in 2015 at approximately 12.8 per cent.

Other observers have pointed to similar statistics. The point, though, is to do what Lawrence does – set the statistics against the stories we tell ourselves. Lawrence concluded her chapter thus:

Are we really the nation of a “fair go” or are we kidding ourselves? In reality, it seems that our comforting and comfortable egalitarian myth, passed down to us in stories of brothers in the bush and mates in the trenches, is blinding us to the growing divide in our society and the need to do something about it.

Lawrence also politely pointed out that egalitarian values were not uniquely Australian but common to many Western liberal democracies.

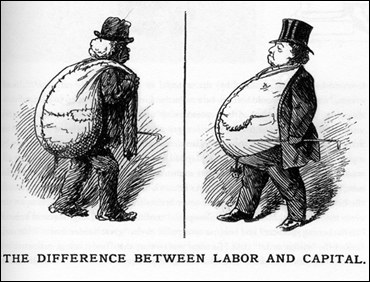

Anonymous cartoon, United States, 1887 (All the World Over)

Anonymous cartoon, United States, 1887 (All the World Over)

Australia has never been an egalitarian society. It never was the land of the ‘fair go for all’, just the land of the ‘fair go and see where we end up’.

The basis for the country, as we keep being reminded of daily, was laid by convict labour, convicts who were exploited by rich and semi-rich landowners, who had in turn taken the land away from the original inhabitants. Emancipation, which enabled convicts to start making something of their own lives, did not come easy, or swift.

The land is hard when not properly looked after, and is too big for large organised human enterprise in most parts. The stockman, often presented as the epitome of the outback Australian, was quite often poor, and was exploited by the people who owned the cattle, sheep or brumby stations. Miners slaved away for the mine-owners in horrible conditions, backpackers pick(ed) fruit for orchard-owners for the lowest of wages. The poor usually band together to share what they have, but there’s no significant example that corporations/owners of companies/land ever supported the poor in a significant and wholesale way to ‘have a fair go’.

Australian cities had their slums and populations of poor people throughout our entire history, and no corporations in our written history were really putting any money towards creating an egalitarian society. That’s not their job, but the Government’s (they reason). And the Government’s record on social welfare is, to say the least, patchy throughout our written history.

The idea of mateship is not based on social equality, but on the most basic of human emotions, namely to save another member of your species at a time of extreme peril (because you would like to expect the same treatment if it was the other way around. Many animals share the same instinct). And even then, it will extend mostly to people that you actually know, or resemble you. Once other human beings are further removed from you (physically and/or socially), and/or the peril that they are in is less direct or distinct, mateship quickly diminishes. People will protest the deportation of a family of refugees that have lived in their community for years, but will maintain that the entire ‘stop the boats’ policy, including the camps on Nauru and Manus, is justified. Mateship, in many cases, equals parochialism. Except in the armed forces, where mateship is based on facing perils together with your squaddie buddies. Which is a feature of all armed forces across time and space.

So all in all, there is no basis for any specific Australian ‘solidarity, mutual respect and mateship’ in Australian written history as the PM claims.

There were only individual instances in history where some people were kind to each other. And people being kind to each other is good, and worth celebrating. But that’s no basis for a corporate tax cut.