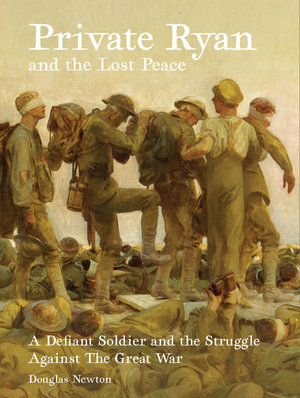

‘Everyman as soldier: how men in suits in drawing rooms conned the people – and their families – into fighting on’, Honest History, 28 May 2021

The commemoration industry in Australia is too much about how we fight and not enough about the far more important questions of why we fight and whether it was worth it. Douglas Newton’s new book shows how problematic that ‘why’ question really is. If we fought our wars for the reasons Newton provides evidence for, it is no wonder that our governments then and our Anzackery[1]-peddlers now have preferred to steer away from that crucial ‘why’ question.

The most important parts of this book are Appendix 4 (War Aims and Secret Treaties of Britain and the Entente Powers, 1914-1918) and Appendix 5 (Lost Opportunities for a Negotiated Peace, 1914-1918). Appendix 4 has 35 treaties, of which 20 were ‘secret’ at the time they were made, and just 15 ‘public’. Appendix 5 has 45 entries, the first the day after the war began and the last four months before the Armistice.

The most important parts of this book are Appendix 4 (War Aims and Secret Treaties of Britain and the Entente Powers, 1914-1918) and Appendix 5 (Lost Opportunities for a Negotiated Peace, 1914-1918). Appendix 4 has 35 treaties, of which 20 were ‘secret’ at the time they were made, and just 15 ‘public’. Appendix 5 has 45 entries, the first the day after the war began and the last four months before the Armistice.

Just think about that: while young men were being blown apart or drowned in mud on the Somme, wading ashore at Gallipoli, freezing to death on the Eastern Front, and dying in the desert in Palestine, and young women nurses were being traumatised by what they saw in the dressing-stations and wards, diplomats and politicians in plush drawing rooms and palaces were making calculations and deals about territory and trade-offs across the world. ‘Service and sacrifice’, that popular euphemism for what men and women do in war, does not really cut it. ‘Deception and dissembling’ comes closer as a description of what happens behind the lines.

Two of the secret treaties, the Straits and Persia Agreement of March 1915 and the Treaty of London of April 1915, are of particular interest to Australians, though we knew little or nothing about them at the time. Under these agreements between Britain, France, Italy, and Russia, ‘Russia stood to gain the great bulk of the plunder to be won through the Gallipoli campaign’, Italy scored territory around the Adriatic Sea, and in Africa – Britain and France were to do well there, too – in return for taking up arms against Austria-Hungary. In essence, Australians died at Gallipoli to deliver slabs of Ottoman Empire territory to Russia and Italy.

Almost from the beginning of hostilities in 1914, and certainly as the ‘industrialised slaughter’[2] intensified by 1916, individuals and groups around the world, from Colonel House on behalf of President Wilson to Lenin and Zinoviev and other European socialists, were arguing for negotiations and peace. Newton summarises why these efforts came to nothing: the generals had more battles planned; ‘explosive power’ might redeem the losses suffered or ‘bring a healing victory’, or even restore political fortunes.

Most of all: ‘The dead soldiers, “the fallen”, it could be explained for ever and a day, had “laid down their lives”, had made “the supreme sacrifice” … ‘ (Newton, page 86). So, more had to die to ensure the previous deaths had not been in vain.

That combination of arguments persisted till the Armistice: ‘they shall not have died in vain’, ‘this will be/we are on the verge of/we need to wait for the knockout blow’, ‘we shall carry on till the bitter end, the last man and the last shilling’, ‘no Peace without Victory!’ Nothing about land and money, future territory and profits.

Specifically, what were the war aims, secret or reluctantly revealed or sometimes even made public? In the beginning, it was ‘avenge Plucky Little Belgium’, but this soon morphed into ‘crushing Prussia’, militarily and economically, expanding the Empire (and France and Russia) by gobbling up German, Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian territories, and commercial pay-offs in spades. ‘Articles [of treaties and agreements] were sprinkled with special provisions about who would build what railways and who would enjoy “the priority of right of enterprise and loans” …’ (Newton, page 96).

Whenever opportunities for peace flickered, those visions of territorial and economic gain, objectives that might be reached by a ‘fight to the finish’, plus the images of all those dead soldiers who must not have died in vain, rose up. And the slaughter went on, to ‘the bitter end’.

Beneath the ‘big picture’, Newton has delved into the story of Private Ted Ryan, and it is the mixture of the global and the personal that is the key strength of this deeply satisfying book. Newton’s technique is to contrast what is happening to Private Ryan – fighting, deserting, going absent without leave, hearing news from home – with events on the European and global scale.

Ryan remains rather a mystery, though, even after Newton’s 300 pages. From when he enlists in September 1915 to his discharge in 1919, he has a relatively brief period at the front, becomes ill, is wounded, suffers PTSD, and is court-martialled four times, essentially for wandering away from the army which, given what the AIF offered in 1916-18, seems a rational action. At one court martial, he is sentenced to death for desertion, but commutation follows, and he spends time in prison. Back in Australia, he marries, has children, and dies at 52 after a bicycle accident. That was in 1943, well into the next war, the one that sprang from the botched peace of 1919.

Menin Gate at Midnight: Will Longstaff 1927 (Wikipedia)

Menin Gate at Midnight: Will Longstaff 1927 (Wikipedia)

Ryan makes two brief pithy statements about the pointlessness of war. The first and longer one was a letter to British Labour man, Ramsay MacDonald, in October 1916.

You are not one of those bitter-end fighters, [Ryan wrote] or one of those who believes in fight to the last man & at the same time stops at home, far away from danger yourself … So far I have not spoken to one man who wants to go back to the firing-line again. [E]very man I have spoken to is absolutely sick of the whole business … I hope you will do everything in your power to bring about a Peace & save this slaughter of Human Lives (quoted, Newton pages 297-98).

Then, in September 1917, Ryan wrote:

I enlisted to fight for a Peace without conquerors or conquered, as a Peace under those conditions as [does?] nothing to justify another war, either as a war of revenge by the Conquered, or a war of Glory and Patriotic land-grabbing by Conquerors (quoted, Newton page 300).

The roots of Ryan’s feelings – apart from the effects of his immersion in total war – are a little unclear. He was a child of Broken Hill union radicalism, perhaps an admirer of the Scots socialist, Keir Hardie, and had some knowledge, censorship notwithstanding, of stirring events in Australia (conscription referenda and anti-war unrest, strikes) and abroad (Russian revolutions). Yet, in a couple of his court-martials, he avoided making a political stance.

In another court martial, though, Ryan provided ‘a denunciation of the war-makers’ vainglory’ that could have come from anywhere on the world-wide anti-war front. ‘Ryan’s accusations – that the war was a war of conquest and that those directing it had slammed the door on good prospects for peace’ (Newton, page 207) could have been said in Australia, Britain, France, Germany or the United States.

So, Ryan is depicted against the background of the war, in context. But there are also parallels with Australia in recent years. Newton suggests more than once, for example, that Australian governments during the Great War were often not privy to the secret treaties and not aware of the efforts made to stop peace initiatives. That would have suited Tony Abbott, had he been prime minister in 1915, rather than a century later. Abbott said this at the Anzac Cove Dawn Service in 2015:

Few of us can recall the detail, but we have imbibed what matters most: that a generation of young Australians rallied to serve our country, when our country called, and they were faithful, even unto death.

Then, ‘Australians don’t fight to conquer’, Abbott told Australian soldiers returned from Afghanistan, ‘we fight to help, to build and to serve‘. That sounds rather like War Aims of the British People, published in 1918 by the National War Aims Committee: Britain sought ‘justice for others’ and ‘the common salvation of all from the perpetual menace of militarism’ (quoted, Newton, page 242). Not the destruction of Germany, not the expansion of the British Empire, not profits as far as the eye can see.

Abbott is now a member of the Council of the Australian War Memorial and might well become its Chairman after Kerry Stokes retires in a few months. If Abbott gets the gig, look out for a regular diet of platitudinous bilge like those examples above and that Lloyd George, Britain’s Great War prime minister, would have been pleased to spout. The words of John Dos Passos, Great War American ambulance driver and later writer, fit perfectly: these are ‘glittering soap bubbles to dazzle men for a moment’, building a ‘vast edifice of sham’ (quoted, Newman pages 193-94).

Neither Abbott at his worst nor Lloyd George, though, plumb the depths of that other Welshman, the obnoxious and pathological William Morris Hughes, Australian prime minister from late 1915, and ally of the equally nasty press baron, Lord Northcliffe, and his protégé, Keith Murdoch. (I refuse to use the name ‘Billy’ for Hughes; this odious man does not deserve endearment. Newton describes Hughes as ‘a kind of whistling kettle of perpetual outrage’, which is colourful but too kind.)

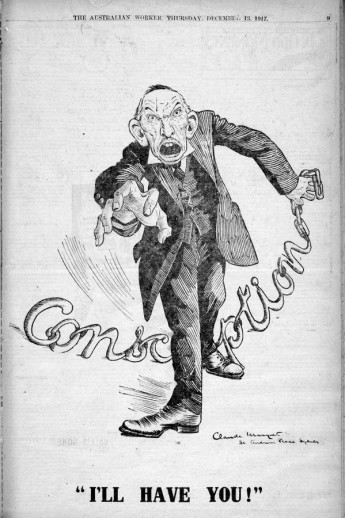

Hughes campaigning for conscription, 1917 (Australian Worker/MOADOPH/Noel Butlin Archive, ANU)

Hughes campaigning for conscription, 1917 (Australian Worker/MOADOPH/Noel Butlin Archive, ANU)

Two Hughes-related snippets will suffice to give a flavour of the man. The first is Ramsay MacDonald’s comment on Hughes as pro-conscription campaigner in Britain in 1916. Hughes had, said MacDonald, ‘DONE MORE THAN ANYTHING ELSE TO RIVET THE CHAINS OF REACTION, OF MILITARISM, AND OF PREJUDICES UPON THE MASSES OF THIS COUNTRY’ (quoted, Newton page 141, using capitalisation from the original in the Barrier Daily Truth).

The second Hughes character reference comes from his own election campaign rhetoric in 1917, where he said Labor, his former political home, was now controlled by ‘extremists’, ‘red-raggers’ and ‘disloyalists’, people who had ‘no God, no Country, and no Flag’. President Wilson’s search for ‘Peace without Victory’ was ‘an appeal to the most craven, ignoble instincts’. Hughes wanted instead a ‘decisive victory’. ‘We are against premature peace’, he shouted. ‘We are for that lasting peace which can come only when the military despotism of Prussia is utterly destroyed’ (quoted, Newton pages 191-92).

Another actor who seems, like Tony Abbott, out of place on today’s stage is Home Affairs Department Secretary, Michael Pezzullo, the little drummer boy. He sounded like a throwback to 1915 or perhaps 1941 when he warned us recently we might need ‘to make the wisest possible choices about sending our warriors to war [and] mobilise the necessary treasure and resources that are required to support the mission of our warriors’. The point that, in an era of cyber-, and possibly germ and nuclear warfare, there would be limited scope and time for a 3rd AIF and keeping the home fires burning seems not to have occurred to him.

That word, ‘warriors’, sounds particularly inapt as a description of soldiers in real wars. But then Australia has always been gung-ho, even at the beginning of the Great War, when others were trying to avert war while Cook and Fisher on the election campaign trail were outdoing each other on the last man and last shilling, and we served up an expeditionary force to the British pretty much before they had even asked for it.

Right through the war, Australians did not know much about geopolitics, nor did we much care. Tony Abbott says Australians today cannot recall the detail; we had little grasp of it then. Here is Hughes in October 1915:

I do not pretend to understand the situation in the Dardanelles, but I know what the duty of this government is; and that is – to mind its own business, to provide that quota of men which the Imperial Government think necessary (quoted, Newton page 134).

For a country which has spun myths about the larrikin independence of its soldiers, we seem to have been remarkably subservient at the government level. It is difficult from this distance to understand quite why. Was the convict stain still so deep that it constrained us from asking questions, pushed us instead to asking, ‘how many?’ and ‘how high?’ Were we so pleased to be able to show our mettle as a military nation that we put up with the political kow-towing that went with it? Why does this subservience persist into the current century?

Back, finally, to Private Ryan. He is himself but he also represents the mass of private soldiers on both sides, the cannon fodder. He is Everyman and Everyman does not deserve to be shoved into the blood and shit of total war at the behest of well-padded and verbose demagogues and vicious outraged whistling kettles. To set against the romantic ‘service and sacrifice’ nonsense beloved of Tony Abbott and former War Memorial Director, Brendan Nelson, and the portentous rhetoric of Pezzullo, Newton offers us any number of actual, real descriptions of war as it was on the Somme. One will suffice:

One is speechless before the spectacle of men, not fighting in the way two angry men would fight, but coolly blasting great masses of their opponents to pieces at long range, and out of sight of each other, till a region with its wrecked towns and homesteads is littered with human bowels and fragments (HM Tomlinson, British war correspondent, 1914, quoted, Newton, page 105).

That is what Ted Ryan railed and rebelled against.

Newton’s book is beautifully produced by Longueville Media, with lots of in-text photographs, an arresting cover (featuring John Singer Sargent’s ‘Gassed’), the Appendices referred to above, nearly 1000 notes, and a comprehensive index. A hardback at $33.75 (25 per cent off from Booktopia) or even at $44.95 RRP, the book is highly recommended. Someone should buy copies for Tony Abbott and Michael Pezzullo.

Ted Ryan, Egypt (?), 1916 (Guardian Australia/Beth Sutton)

Ted Ryan, Egypt (?), 1916 (Guardian Australia/Beth Sutton)

[1] ‘Anzackery’: ‘The promotion of the Anzac legend in ways that are perceived to be excessive or misguided’ (Australian Concise Oxford Dictionary). Use the Honest History website Search engine with search term ‘Anzackery’ to find plenty of references.

[2] John Dos Passos, American ambulance driver during the war and later writer (quoted, Newton page 193).

* David Stephens is editor of the Honest History website.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.