Peter Stanley[*]

‘The Armenian Genocide is part of Australian – and Turkish – history’, Honest History, 16 January 2019 updated

Update 27 February 2023:When We Dead Awaken: Australia, New Zealand and the Armenian Genocide, by James Robins. Details of a book published in 2020.

Peter Stanley reviews Ashley Kalagian Blunt’s My Name is Revenge.

The Armenian Genocide – that is, the Ottoman Empire’s attempt to exterminate its Armenian subjects over the years from 1915 to the early 1920s – has been a part of the physical and emotional memory of the Armenian community internationally for over a century. It would be tempting – but untrue – to say that the Armenian Genocide ‘ended’ almost a century ago because, according to the most widely accepted definitions of genocide, the atrocity continues as long as the fact of the attempt is denied. Sadly, and reprehensibly, the successor state to the Ottoman Empire, the Turkish republic, continues to deny that the Genocide occurred, thereby perpetuating the pain of people of Armenian heritage, even if they themselves are generations removed from 1915.

Because of this continuing pain, Armenian communities, families and individuals still comprehend, reflect upon, and try to come to terms with not just with what their forebears experienced and felt during the Genocide, but also how that event reverberates down the generations. Ashley Kalagian Blunt, an Australian-Canadian-Armenian three generations distant – or perhaps only three generations close to – the Genocide, brings these understandings, insights and, above all, emotions to the reflections in her novella, My Name is Revenge, a finalist in the Carmel Bird Digital Literary Award for 2018.

The book is a powerful work of the imagination and one that is rooted in historical events. Speaking purely pragmatically, the Genocide offered Ms Kalagian Blunt a richer lode than she could possibly mine; the Genocide is the historical plutonium which powers her story. Her great-grandmother, Mariam, survived 1915 as a toddler, but lost not just her family (including twin siblings) but even her real name, knowing only the name of her home village. ‘For the rest of her life’, the author recalls, ‘she sought out other survivors …, asking do you remember a family with twins?’ She never learned any more. Such is the depths of the Armenian people’s tragedy that this powerful family memory – surely a starting point for another story – remains un-quarried. Instead, Ms Kalagian Blunt invents a drama in which Armenian brothers in Australia in the early 1980s respond both to their tragic legacy and to the ignorance of their adopted nation about it.

The novella’s action takes as its starting point the assassination by Armenian ‘Justice Commandoes’ [sic] of the Turkish consul-general in Sydney in December 1980, a real crime never solved. Ms Kalagian Blunt imagines that the murders were committed by a shadowy Armenian hit man-terrorist-freedom fighter, Softie, and Armen, the elder brother of the novella’s protagonist, Vrezh, whose name means ‘revenge’ in Armenian. The very choice of her protagonist’s name illuminates how ‘Armenian communities’, as she observes, ‘have an unhealthy relationship with the past’. Ms Kalagian Blunt’s novella is a brave attempt to jolt Armenian assumptions about their past and to build their capacity to see it in more complex ways.

Armen and Vrezh’s involvement in Softie’s further assassination plans mirror Vrezh’s fascination with Soghomon Tehlirian, who in 1921 assassinated on a street in Berlin Talaat Pasha, one of the principal architects of the Genocide. The novella’s essential action details both Vrezh’s feelings toward the traumatic memory with which his family continues to struggle and his ambivalence about the idea expressed by his name. Ms Kalagian Blunt dramatises Vrezh’s predicament and the decisions he makes, musing on the impact of the Genocide in shaping and even dominating not just the Australian-Armenian community’s life, but that of virtually all Armenians displaced and dispersed as a direct and indirect result of the Ottoman Empire’s murderous intentions.

Sydney Morning Herald coverage 18 December 1980 of the assassination of the Turkish consul-general (Australian Turkish Advocacy Alliance)

Sydney Morning Herald coverage 18 December 1980 of the assassination of the Turkish consul-general (Australian Turkish Advocacy Alliance)

While dealing with inherently dramatic events – the legacy of the Armenian people’s suffering and the protagonists’ involvement in preparing for further acts of revenge – the author retains control of the scale of the tragedy through members of the Melokian family of Lane Cove, recent migrants from Egypt (where the family had been refugees from genocide). She provides, if anything, an understated explanation of their experience of the Genocide – symbolised more profoundly by the demented state of Vrezh’s grandfather, Arshag, who re-enacts the terrors of his childhood while restrained nightly. This is a tragic fragment of the author’s actual family history that she uses purposefully.

Ms Kalagian Blunt’s exploration of Vrezh’s decision to emulate Tehlirian’s actions, which forms the core of her story, is explored more fully, with a resolution that is both tragic and satisfying, but which does not extend to endorsing the idea of revenge killing. Indeed, the author’s sensitive and insightful handling of the power and longevity of historical experience – at least for Armenians – is one of the novella’s most important services.

While the handling of the ‘period’ aspects of the setting is not always assured, many incidental details of the period add to the story’s effectiveness. But some examples suggest the difficulties of getting the historical setting ‘right’. Was ‘overthinking’ a term used in 1981? I think not. Would an Australian high school class in the 1970s have been full of ‘Rebeccas’ and ‘Jasons’? It would instead have had lots of Jennifers, Karens, Davids or Marks; Rebecca and Jason only became popular babies’ names a decade later.

Then, one of the less persuasive episodes in the story occurs when Vrezh attempts to include the story of the Genocide in an Anzac Day address he is obliged to deliver, to objections from a Turkish boy in his class, drawing a response that gets Vrezh expelled. Would Australian history teachers in the mid-1970s have been so receptive to a Turkish denialist reading? Would Vrezh’s fellow students have fallen to ‘cat-calling, taking sides’, as if they understood anything of the protagonists’ views? I doubt it, though they might well have decried both Turks and Armenians perpetuating the hatreds of their former countries.

These minor points of pedantry are, perhaps, a reminder that the past is often further away than we assume. The events of 1980 are now nearly four decades from us but were only 60 years on from the Genocide – a fact that enables Ms Kalagian Blunt to muse on memories and feelings much closer to the events of 1915-23 than would be the case today. Would Australian-Armenian youths today be drawn as powerfully to seeking revenge? Are any Australian-Armenians still named Vrezh, ‘raised to hate’, as the author writes? We can only hope that, while for Vrezh the emotion his name expressed ‘shimmered like a mirage’ in 1980, Armenian-Australians today can take a more rounded view of Armenian historical experience, even while maintaining that the genocide their forebears suffered was among the greatest of crimes against humanity in the twentieth century.

My Name is Revenge is both an imaginative work of fiction and a work reflecting upon history, both what happened and how we might use it. The book includes as an afterword a short exegesis (as it is often called in the creative writing fraternity) explaining the author’s intentions and decisions. This essay, ‘Writing violence, arousing curiosity’, is if anything even more important for those who share the values of the Honest History community – that is, a determination to face the realities and truths of history, despite the pain that such a quest may impose. One of Ms Kalagian Blunt’s aims in writing this novella has been ‘to acknowledge this violence and the trauma that underlies Armenian understanding of the community’s history’, but by focusing on and criticising the idea of retributive revenge she explicitly challenges Armenians to see themselves not ‘only as victims’. Her drama of revenge presents the Armenian story as more ambivalent, and more truthful.

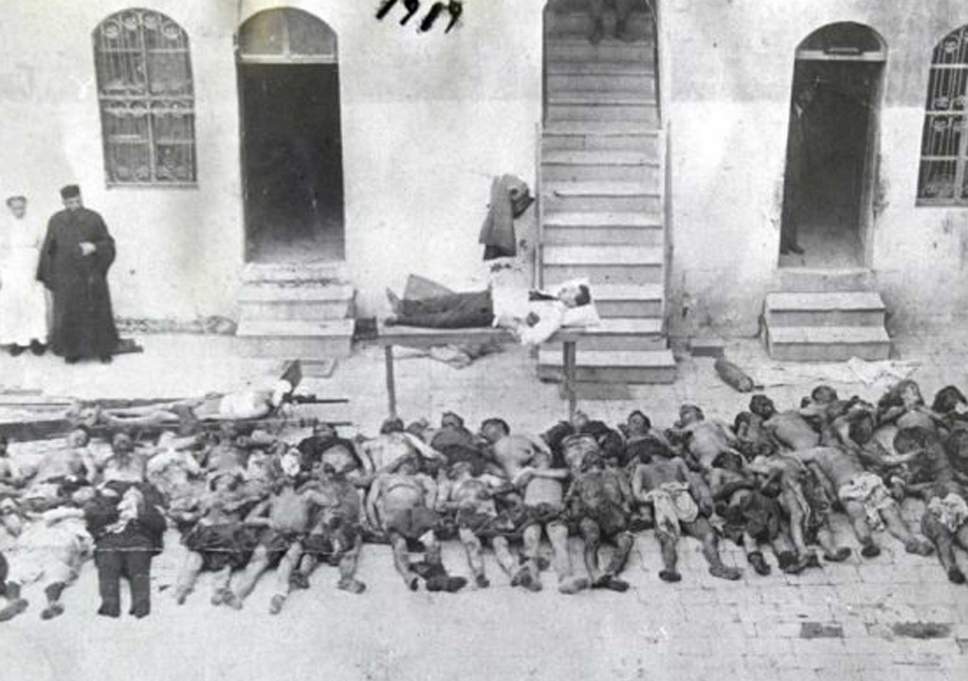

Armenian Genocide victims (The Independent)

Armenian Genocide victims (The Independent)

This is why My Name is Revenge deserves to be noticed by those concerned with honesty in history. Ms Kalagian Blunt’s story is a fine example of why history matters and why we should be pushed to reconsider assumptions about how history was and how it might be understood. And I mean ‘we’ rather than just ‘Armenians’. Just as Australians were and remain a part of the story of the Armenian Genocide (in witnessing it as soldiers and supporting its victims during the 1920s through fund-raising and relief work) so the Armenian story is, as the author observes, ‘part of everyone’s story’. Because descendants of Genocide victims and survivors are now fellow citizens of our nation, our history now encompasses the event and its many ramifications.

[*] Professor Peter Stanley of UNSW Canberra was the first President of Honest History, 2013-17. In the interests of full disclosure, he notes that Ms Kalagian Blunt reviewed his book written with Vicken Babkenian, Armenia, Australia and the Great War (2016), to which she refers in her book. For other Honest History posts by Professor Stanley and on the Armenian Genocide, use our Search engine.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.