‘Not Gallipoli: a visit to Dybbøl, a Danish site of memory’, Honest History, 10 April 2018

What does a visit to Dybbøl tell Australians? It offers a reminder that battlefield commemoration need not be strident, garish or sentimental, that battles regarded as significant in a nation’s past need not be represented in the syrupy sentimental or stridently nationalistic way that Gallipoli has been.

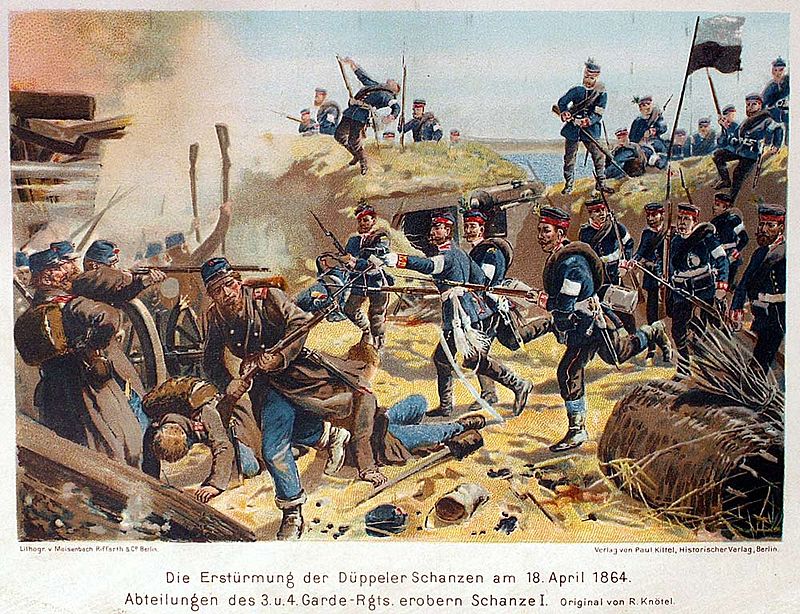

Danish and Prussian troops at Dybbøl during the Prussian invasion of Schleswig. The Prussians bombarded the Danish fortifications and, on 18 April 1864, the Prussians (at right) stormed and took the position at a cost of 1700 Danish and at least as many Prussian casualties (WikiMedia Commons).

Danish and Prussian troops at Dybbøl during the Prussian invasion of Schleswig. The Prussians bombarded the Danish fortifications and, on 18 April 1864, the Prussians (at right) stormed and took the position at a cost of 1700 Danish and at least as many Prussian casualties (WikiMedia Commons).

The battlefield of Dybbøl, located in the Danish region of South Jutland, is probably not top of the itinerary for Australian visitors to Denmark. The statue of Hans Christian Andersen’s Little Mermaid, the changing-of-the guard at the Amalienborg palace and the tourist-trap of the Nyhavn are probably more likely destinations. But Dybbøl is a site with interesting and fruitful reflections to offer an Australian visitor, even though Denmark’s long history of Baltic imperialism, national identity, and war and neutrality is quite different to Australia’s.

Denmark today is a small nation of just over five million people, occupying a cluster of islands at the mouth of the Baltic. Neutral in the Great War, Denmark was occupied by Nazi Germany in 1940 and is now part of both Nato and, with some misgivings, the European Community. It shares the Scandinavian reputation for progressive and rational social policy, good design, and dark crime dramas featuring characters wearing chunky knitted sweaters. Its history before, say, 1940 may understandably be hazy to many Australians.

In fact, Denmark’s history for 400 years was shaped by imperial ambitions, religious and dynastic conflict, and protracted wars against its Baltic neighbours. Its pretensions to be a regional power ended only at the conclusion of ‘the English wars’, their part of the Napoleonic wars, when British naval power destroyed Denmark’s large fleet (partly in the battle in which Horatio Nelson famously declared that he really could not see the signal).

In the aftermath of the Congress of Vienna, Denmark’s absolute monarchs found themselves at odds with the liberal and nationalist spirit of the age. This was the more so because Denmark’s domains included both Danish and German-speaking subjects, whose different aspirations brought both civil war in the 1840s and the intervention of Denmark’s more powerful neighbours as part of Germany’s drive for unification in the 1860s. It was conflict over the rule of the German-speaking provinces of Schleswig and Holstein in the early 1860s, abetted by a seemingly suicidal policy on the part of Denmark’s ruling elite, that brought about Denmark’s war with Prussia and Austria in 1864, a conflict that culminated in defeat for Denmark at the siege of Dybbøl.

Filming 1864, which became the most expensive and elaborate Danish television series yet made. Despite minor and pedantic criticisms of, for example, the details of uniforms, the production was widely praised, not least for its realistic and often graphic depiction of the realities of combat (supplied).

Filming 1864, which became the most expensive and elaborate Danish television series yet made. Despite minor and pedantic criticisms of, for example, the details of uniforms, the production was widely praised, not least for its realistic and often graphic depiction of the realities of combat (supplied).

Like many Australians, while I was aware of the fact of the 1864 Prussian-Austrian war with Denmark, I had little idea of its causes, course or consequences until, in mid-2016, SBS broadcast Ole Bornedal’s television drama series 1864. Based on non-fiction books by the Danish author Tim Buk-Swienty, 1864 told the story of the war against the dramatic relationship between two brothers, a woman they both love, and a villain in the form of a cowardly and caddish captain.

The fictional characters in 1864 exist alongside historical ones, including the flawed Danish prime minister, Ditlev Monrad, the wily Prussian chancellor Otto von Bismarck and monarchs and military officers on both sides (including the war hero Lieutenant Wilhelm Dinesen, father of the writer Karen Dinesen, author of the stories that inspired the films Babette’s Feast and Out of Africa). Bornedal’s powerful and seemingly well-based historical drama impelled me to read one of Buk-Swienty’s books, also entitled 1864, and, in due course, to visit Dybbøl, the setting of the climax of the series.

Denmark’s defeat in 1864 was arguably a more profound event in modern Danish history than any other; more than the bombardment of Copenhagen by the British, the German occupation of 1940-45 or Denmark’s entry into Europe. The settlement imposed by Prussia and endorsed by the great European powers cost Denmark 40 per cent of its former territory and 40 per cent of its people, making it a small, unitary and culturally unified nation, and impelling it to excel within its reduced borders.

Denmark responded to defeat by looking inwards. Within a couple of decades an intensification of agricultural effort brought as much new land into production as had been lost by the excision of Schleswig-Holstein. It inspired Danes to define their national identity by what they could create socially and culturally, as a minor power humiliated by larger neighbours.

The symbol of that defeat was Dybbøl, though the battlefield became part of the territory claimed by Prussia, and in turn became part of Germany until, in the aftermath of Germany’s defeat in the Great War, it was returned to Denmark in a plebiscite overseen by the victorious allied powers. The transfers of ownership give the site of Dybbøl a complexity and a power that can best be appreciated on the spot.

The ruins of the Prussian memorial, destroyed by Danish patriots in 1945, with Dybbøl Mill and its large Danish flag in the background (Peter Stanley)

The ruins of the Prussian memorial, destroyed by Danish patriots in 1945, with Dybbøl Mill and its large Danish flag in the background (Peter Stanley)

How did Dybbøl become the scene of the decisive battle in 1864? The Danish military strategy in 1864 was as misguided as its political and diplomatic blundering that brought about the war, a reflection of the dysfunction of the Danish regime that took the nation into such a pointless war. Faced with a more powerful opponent on land, Denmark’s commanders (who had welcomed and even sought the war) chose to withdraw from an outmoded defensive position of doubtful worth (the historical Dannevirke lines) and to try to defend a series of defensive redoubts on a rolling ridge at Dybbøl, fighting with the troops’ backs to the narrow strait of Alesund, a position which the Prussian and Austrians could bombard virtually with impunity.

Withdrawing through the depths of a winter (an ordeal vividly depicted in Bornedal’s film), the Danes held the line at Dybbøl through a dreary spring as the Prussian shells rained down on demoralised troops and destroyed half of the town of Sønderborg, on the shores of Alesund. The two sides faced each other for several weeks until, on 18 April 1864, the invaders launched a massive attack and broke the Danish lines. (The conflict saw various subsidiary actions, such as a Danish naval victory off Heligoland, in the North Sea, but the defeat at Dybbøl effectively ended the war.)

Visitors to Dybbøl today mostly arrive from Sønderborg, that is, from the Danish side. The ridge on which the Danes entrenched is about two kilometres from the crossing to Sønderborg and comprises several linked sites. Most obvious is Dybbøl Molle, the windmill which became for Danes a symbol of the battle. The huge mill, which had been destroyed under Prussian bombardment (and, indeed, had been rebuilt after Dybbøl became a scene of battle in the civil war fought to keep Schleswig-Hostein Danish some 14 years before) became, even under German occupation, the focus of Danish remembrance. Today, it and the nearby 1864 Historiecenter Dybbøl Banke are both operated by the Sønderborg Museum, though they project quite different interpretations of the battle and its significance.

The Historiecenter Dybbøl Banke is a large, modern interpretive centre of the kind familiar from other battlefields in Britain (Culloden or Bosworth), Europe (Ypres/Ieper or the Somme) or the United States (Gettysburg). It is particularly good at putting the battle and the war in a broader context of European politics and in using the familiar technique of ‘personal stories’ to make the action intelligible to visitors uninterested in the strategy or the tactics. It uses film (seemingly presented only in Danish and German), contemporary photographs (the war was one of the first to be documented by photographers) and especially reenactments to communicate with visitors. A simulated ‘soldiers’ town’ in the grounds of the centre offers opportunities to dress in uniforms, watch a cannon being fired, try soldiers’ food and locate objects seeded in the ground using a metal detector.

The Historiecentre, where visitors watch demonstrations by guides dressed in Danish and Prussian uniforms and civilian costume (Peter Stanley)

The Historiecentre, where visitors watch demonstrations by guides dressed in Danish and Prussian uniforms and civilian costume (Peter Stanley)

Though evidently based on solid historical expertise, the ‘Historiecenter’ is squarely aimed at Danish families wanting an undemanding day out. It also caters to a small but significant proportion of German visitors (you can see Germany from the ridge which Dybbøl occupies) and many of the captions, audio-visual displays and activities are aimed at them (e.g. ‘Erzählung in deutscher Sprache: Story in German special tour for our German guests’).

But Dybbøl is now in Denmark and it overwhelmingly tells a story of profound significance to Denmark. As anyone who takes even a casual interest in the broadcast of the Eurovision song contest or the Tour de France must become aware, flags have a profound importance in Europe. National, regional and municipal flags abound, often carrying powerful political messages.

One of the curious phenomena at Dybbøl, however, is the relative dearth of flags, in three ways. First, as in Denmark as a whole, the national flag (the Dannebrog) is not much in evidence. (By contrast, Swedish national flags are seen in abundance in Stockholm, on virtually every holiday house in the Stockholm archipelago, on every boat, private or official, on Stockholm’s waterways.) Despite the Dannebrog’s claim to embody the Danish spirit, there are just a few Danish national flags at Dybbøl, one at the mill, several at the Historiecenter, but none on the battlefield itself, and very few in any part of the residential area of Dybbøl, now a suburb of Sønderborg. Houses on the road between Sønderborg and Dybbøl have flagstaffs, but none of them were flying any flag, and even the Dannebrog at the mill is only flown in the tourist season between 1 April and 1 November. If Dybbøl has a symbolic power for Danes that symbolism is not manifest vexillogically.

The other vexillogical absences at Dybbøl are that, although Denmark is part of the European Community (as is Germany, of course) the European flag is strikingly absent, despite the rhetoric of reconciliation that some parts of the site express. (Once West Germany and Denmark became part of Nato and then Europe from the 1950s, the battlefield became a crucial site of reconciliation between nations that had been at odds between 1864 and 1920 and 1940 and 1945.) While virtually all interpretive panels offer German text (and usually also English) there are no German flags to be seen at Dybbøl.

One of the few exceptions to these absences is a moving memorial commemorating the first time that the Red Cross appeared on a battlefield, when Prussian and Danish representatives of the infant Red Cross worked to relieve the suffering of the wounded of both sides. It records the success of the use of neutral humanitarian, workers, the first of many thousands who have made such a difference in succouring those affected by war over the following 170 years.

The museum at Dybbøl Mill displays one of the few surviving fragments of the Prussian memorial, including a bas relief depicting the fighting (Peter Stanley)

The museum at Dybbøl Mill displays one of the few surviving fragments of the Prussian memorial, including a bas relief depicting the fighting (Peter Stanley)

Other absences can be identified on the battlefield. First, the very terrain is not what it seems. The battle essentially entailed a Prussian-Austrian siege of a line of fortified Danish earthworks; a line of fortifications can be seen and visited on the field today. It takes little imagination to imagine both the ordeal of the protracted Prussian bombardment or the desperate fight when the attackers launched a huge infantry assault on 18 April 1864. But the earthworks visible today are not those of the defending Danes. They are the remains of new, larger fortifications built by the Prussians in 1865.

Secondly, there is a striking absence in commemoration. Following the battle the Prussians erected a memorial, the Düppel Denkmal, reflecting the significance of their victory. (In a reflection of the linguistic differences that provoked the conflict, the place’s German name differed from its Danish name.) The significance of Dybbøl (or rather Düppel) in Germany’s rise from a collection of states to a powerful, unified nation, was that, as was said in imperial Germany, no Düppel, no Königgrätz (the Prussian victory over Austria in 1866); no Sedan; no German empire. Victory at Dybbøl/Düppel supposedly set Germany on its path to imperial glory.

The German memorial, erected on the site of one of the former Danish fortifications, became the focus of German commemoration between the memorial’s dedication in 1872 and the return of the region to Denmark in 1920. The memorial remained until 1945 when, in the wake of the Nazi defeat (and the end of the German occupation of Denmark) Danish patriots blew it up, and only one part of a bas relief depicting Prussians and Danes struggling hand-to-hand is now visible, on display in Dybbøl Molle.

The admission prices for the Historiecenter and Dybbøl Molle might suggest their relative value – 125 Danish kroner compared with just 25 – and visitors enter the mill through a gift shop and are offered a more extensive presentation on the mechanics of milling than most probably want or need. In fact, Dybbøl’s other major interpretive site, the mill’s displays offer informed and sophisticated insights into not so much the events of 1864 but rather into the processes of remembering and forgetting in the complex environment of this part of South Jutland as it has changed hands, back and forth, since 1864.

While the Historiecenter focusses on evoking the causes of the 1864 conflict, the experience of the battle and the consequences for the region and the protagonists, the less flamboyant presentation at the mill is more reflective, illuminating balanced and, in fact, honest. It repeatedly informs visitors prepared to read the minute captions in its exhibition gallery – captions which are, thankfully, repeated virtually word-for-word in a booklet available for purchase.

The mill’s collection includes some items relating to the battle, though even here it undercuts conventional interpretations of heroism. For example, in offering examples of heroic figures celebrated by each side, a showcase seems to tell what seems to be a conventional story about the heroic Prussian Pioneer Klinke. This man, who supposedly gave his life in an attempt to break into a Danish redoubt on 18 April 1864, was celebrated as a hero by German writers for decades. But doubts emerged later in the century, and it came clear that Klinke had been given the glory earned by another. Should the truth be conceded? Kaiser Wilhelm II had no doubts: ‘depriving the people of their hero is not the thing to do’, he declared.

Dybbøl Mill. The original mill was destroyed by the Prussian bombardment, but was rebuilt and is now the second most prominent historical site on the battlefield. The several Danish flags at the mill are almost the only Danish flags visible on the site (Peter Stanley).

Dybbøl Mill. The original mill was destroyed by the Prussian bombardment, but was rebuilt and is now the second most prominent historical site on the battlefield. The several Danish flags at the mill are almost the only Danish flags visible on the site (Peter Stanley).

For Australians, Dybbøl offers an obvious comparison. Here is a battle – a defeat – which contributed to a powerful national identity; sound familiar? The comparisons with Gallipoli are seductive, though not exact. In this case, the battlefield is owned by the loser, not the victor, and historical opponents can readily visit the site. While Dybbøl has been the occasion for reconciliation (as Gallipoli has been in pursuit of Turkish diplomatic objectives) it is not a major scene of pan-European fellowship. But for all its significance as an event which changed the entire tenor of modern Danish history, Dybbøl is no Gallipoli, in the sense of providing a focus for nationalist mobilisation. The relative absence of flags or any other sort of national symbolism, such as recent memorials, plaques or other manifestations – as are common on Gallipoli, by both Australia and Turkey – is surely telling.

What does a visit to Dybbøl tell Australians? It offers a reminder that battlefield commemoration need not be strident, garish or sentimental, that battles regarded as significant in a nation’s past need not be represented in the syrupy sentimental or stridently nationalistic way that Gallipoli has been (again, by both Australia and Turkey). Dybbøl suggests that we can appreciate both the human and political importance of a battle in a balanced, dispassionate manner, devoid of both the distortions of excessive and unproductive emotion and of the excesses of politicisation such as Australia has seen on its Dybbøl.

* Peter Stanley is Research Professor in History at UNSW Canberra and Immediate Past President of Honest History. As well as his more than 30 books on military and social history, he has written for Honest History on commemoration in Norfolk Island, Turkey and the United States. For his other material on Honest History, use our Search engine.

The author beside the Copenhagen memorial depicting a celebrated incident in the 1864 war. Despite the significance of the war the memorial stands on a busy street, not accorded any attention or any special space (Claire Cruickshank).

The author beside the Copenhagen memorial depicting a celebrated incident in the 1864 war. Despite the significance of the war the memorial stands on a busy street, not accorded any attention or any special space (Claire Cruickshank).

Like Leighton, I lived in Denmark in the late 1990s and was struck in those days by the abundance of Danish flags. It was normal even for private birthday parties to be festooned with Danish flags and there were certainly a lot of flags in the streets and in businesses. Maybe August, the height of the holidays, offers a pause in flag display.

I am very fond of Denmark and my Danish friends, but I think that the subdued treatment of Dybbøl is not a manifestation of a notably calmer patriotism. For one thing, the right-wing nativist Dansk Folkeparti has done much better in Danish elections than PHON in Australia, winning 21% in 2015. There is (i.e. was in my time) much less public denunciation of xenophobia than in Australia, too.

If the celebration of Dybbøl is muted, it may be because Danes rest their national identity much more on culture than on history. That culture is attractive, of course, but it tends to exclude outsiders more effectively than does a focus on history.

Peter … that is very interesting … perhaps it has something to do with a reaction by the younger generation to the older? I can even recall the story of a foreigner being (politely) asked to take down their national flag in one of the suburbs as only the Danneborg were allowed to be displayed in Denmark unless it was at a foreign mission or Ambassador’s residence.

Hello Leighton Views

Thanks – a useful comment based on your personal experience. I must say that I expected the Danish national flag to be more prominent in Denmark, given the population’s ambivalence over the EU. But I was struck by the relative scarcity of flags, especially compared to Sweden, where they were absolutely everywhere, on houses, boats, ferries, even on buses (along with rainbow flags for Stockholm’s annual gay mardi gras). I’m sure it is more noticeable on high days like 9 May – but in a week in August it was very scarce, I thought.

Nicely written … though having lived in Copenhagen for a couple of years in the late 1990s, Peter’s thought that the Danneborg, or Danish national flag, is not front and center for the Danes was surprising. Unless things have considerably changed in the last twenty years, the Danneborg was front and center at every celebration in Copenhagen and was very prominent around the city … particularly at such personal occasions as birthdays. A very noticeable day when emphasis was placed on the flag (half-mast till noon, and then at full-mast) was the 9th of April, the day Denmark was liberated by the British Army at the end of World War II. A somewhat ironic event in light of the 1801 bombardment of Copenhagen by the British fleet under Nelson which destroyed much of the city.