‘Dawn, Emily Bay, Norfolk Island, Anzac Day 2015’, Honest History, 27 April 2015

What may be Australia’s first dawn service is held each Anzac Day at Emily Bay on Norfolk Island. (They may get up as early on Lord Howe Island, some distance to the south but closer to Sydney, so I’m not making any claims I can’t substantiate, and with a limited internet connection I can’t easily.)

I arrived at the Emily Bay foreshore just after 5 am. The service was held in a grassy clearing, within a couple of hundred metres of the surf washing over the bar protecting the bay and under massive Norfolk Island pines 30 or 40 metres high, perhaps dating back to the earliest European settlement on the island, a few weeks after the arrival of the First Fleet at Sydney Cove. The site was marked by a line of coloured light bulbs, an incongruous touch for a setting of such solemnity.

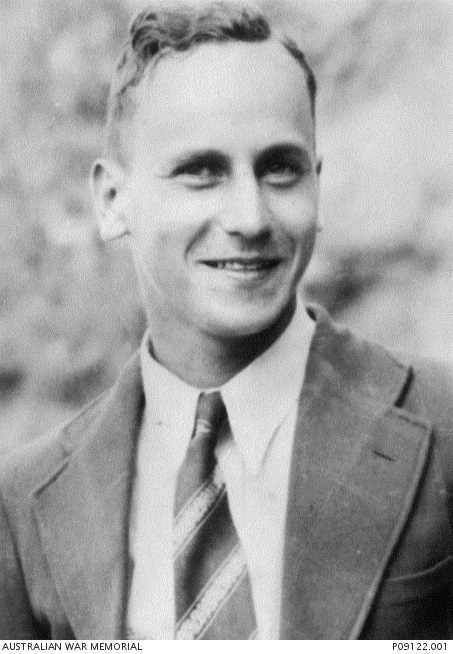

Acting Lance Corporal Allen Christian, 2/20 Battalion, of Burnt Pine, Norfolk Island. missing presumed killed, Malaya, 15 February 1942, aged 23 years (Australian War Memorial P09122.001)

Acting Lance Corporal Allen Christian, 2/20 Battalion, of Burnt Pine, Norfolk Island. missing presumed killed, Malaya, 15 February 1942, aged 23 years (Australian War Memorial P09122.001)

A crowd of maybe 200 people were gathered when I arrived, growing to perhaps 500 later, quietly sitting or standing about while waiting for the ceremony to begin. The dozens of private cars parked along the foreshore beside the ruins of the Kingston convict settlement testified that a good proportion of the island’s 1500 people had attended, while the presence of several tour buses suggested that tour groups, mainly of older Australians, attended. Indeed, the crowd overwhelmingly comprised people over 60 years of age, whether islanders or visitors.

Very few children were present, though they would perhaps be more visible at the march and ceremony held at the nearby war memorial later in the morning. As might be expected, this was an Anzac Day reflecting what might be called Old Australia. Residents or tourists, there seemed to be no sign here that Australia had become a multicultural nation.

The setting was simple. Several rows of plastic chairs faced a portable lectern 20 metres away across the grass, confirming the Australian disinclination to be too close to speakers at any occasion, from a retirement presentation to a book launch. The focal point of this ceremony was a flame of remembrance burning in what could have been a shell case, but standing on a picnic table doubling as a sort of temporary cenotaph, a fitting symbol given the island’s economic dependence upon tourism.

At about 5.20 the MC invited ex-service men and women to form up beside the flame of remembrance and about 20 people did so, mainly men in their seventies or older, but including a few younger former members of the Australian Defence Force, a couple in uniform. Several of the older men wore the blazer-medals-badges-beret combination favoured by veterans of remembrance services as well as wars. Norfolk Island’s RSL and its supporters strongly adhere to the idea that Anzac Day should especially honour those who have served and who are serving, as well as remembering those who served and died.

Soon after, five teenaged army cadets arrived, unarmed, and after some quiet disputation – they may have practised at a different picnic table – formed up to slow-march into position as a catafalque party around the flame, maintaining an impressive stillness throughout the ceremony.

The MC, who modestly neither introduced himself nor allowed his name to appear in the program, called the ceremony to order at 5.40, when the sky was still dark, stars visible overhead. The overcast and blustery weather of the past few days had cleared, and the foreshore was virtually windless.

The ceremony opened with a ‘Prologue’ delivered by the sub-branch’s president, Mr Warren Finch, comprising a long quotation from what evidently was an account of the first landing on Gallipoli, given by a British naval officer to official correspondent and historian Charles Bean later in the war. It provided an almost textbook example of why eyewitness accounts should not necessarily be accepted. It included at least three clear errors (that 12th Battalion men became ‘mixed up’ with men of the first wave, that machineguns met the first landing and that Ottoman artillery fired at the men coming ashore). It made little sense as a description of the events being commemorated. In fact, to anyone who did not already know the story of the 25 April 1915 invasion it would have done little to explain why, a century later, a good proportion of the island’s inhabitants should rise in the darkness and gather at a beach as they were.

Effectively a classic country-town dawn service, the Emily Bay ceremony included the sorts of endearing clangers absent from the smoothly stage-managed ceremonies of the capital cities. There was no music, live or recorded (though the MC led the a capella singing beautifully), the recording of the Last Post stopped for a few bars and as usual almost no one sang the hymns. But this was a community ceremony and at its emotional heart was, as always, the Last Post, the recitation of Lawrence Binyon’s Ode and the minute’s silence. Those present around me joined in the ‘Lest we forget’ and ‘We will remember them’ with quiet assurance. Regardless of the tired and historically dubious official rhetoric, the squabbles over symbolism and the intrusion of media and marketing in larger ceremonies, this service reflected the desire – perhaps even the need – for a community to remember.

Private Eustace Adams, 19th Battalion, of Norfolk Island, wounded Pozieres 1916, killed Zonnebeke, 29 September 1917, aged 23 (Australian War Memorial P08674.001)

Private Eustace Adams, 19th Battalion, of Norfolk Island, wounded Pozieres 1916, killed Zonnebeke, 29 September 1917, aged 23 (Australian War Memorial P08674.001)

Several men from Norfolk Island took part in the 25 April landing, though the first of 13 islanders to die in the Great War died in the August offensive. Another ten died as a result of fighting on the Western Front, the last on 25 April 1918, presumably at Villers-Bretonneux. More strikingly, perhaps, of the nine islanders who died in the Second World War, eight died either in the fighting for Singapore (two) or as prisoners of the Japanese, on the Burma-Thailand railway, in Japan or in the long agony of Sandakan. Most bore surnames familiar from the Bounty-Pitcairn story, and they almost certainly had relatives among those attending the ceremony.

The Emily Bay ceremony offered a reminder that Anzac Day and remembrance spans both the links of family and community and the grander official agenda of nation-building and identity. Perhaps the best explanation for its survival, and indeed its flourishing condition, is its capacity to encompass, in Charles Bean’s words, both the ‘large and the small’.

What made the 2015 ceremony especially notable was that it occurred in the midst of a slow-burning and little-reported confrontation between the islanders and their little elected assembly and the Australian federal government, represented at the service by the island’s Administrator, Mr Gary Hardgrave. Essentially, the islanders are facing what is in effect a hostile take-over by the Australian government, a take-over which is expected to end self-government in exchange for compulsory entrée to both the Australian benefits system, but also its taxation system and regulatory regime. Whether this will be in the islanders’ best interests is, it seems, both uncertain and of no interest to the federal government.

Mr Hardgrave delivered the address, a classic of the genre of Anzac address rhetoric, in which he asserted the supposed relationship between the invasion of Gallipoli and the formation of the national character and acknowledged the bonds between Australia and New Zealand. Like Mr Finch’s Prologue, Mr Hardgrave’s address included historically doubtful propositions. For example, he led us to believe that boys as young as 14 took part in the landing on Gallipoli and strongly implied that only men from ‘regional Australia’ volunteered for the Australian Imperial Force, two factoids that should be challenged as untrue.

As expected, Mr Hardgrave referred to but only paraphrased the ‘Atatürk quotation’, which asserts that Australia’s Gallipoli dead are supposedly regarded as Turkey’s sons as well. The recent work of Guardian Australia journalist Paul Daley and Honest History’s secretary, Dr David Stephens, in exposing that the quotation was almost entirely made up long after Ataturk’s death, has sadly not reached Norfolk Island. Those attending the service at Emily Bay were only the first of millions attending this year’s ceremonies to be misled yet again by this lamentably successful propaganda.

Having been hearing for several days of the importance of which anthems would be sung at the ceremony I was eager to learn of the outcome. The islanders, who are, and yet are not, part of Australia, do not sing ‘Advance Australia Fair’. They have retained ‘God Save the Queen’ and sing the ‘Pitcairn Hymn’, a relic of the island’s heritage as descendants of the Bounty mutineers, who arrived on Norfolk Island in 1856. In this the islanders prevailed: ‘Advance Australia Fair’ was not on the program; Norfolk Island was perhaps the only place in the Commonwealth which did not sing the national anthem.

One of the most poignant parts of the ceremony was the singing of the Pitcairn Hymn, which follows a complex meter and a tune known only to islanders. Though the islanders advocate self-government, not all of those present seemed willing to sing (a characteristic they share with Australians) and the MC carried the tune virtually alone, singing into the microphone in a strong tenor. The archaic words, composed in the early nineteenth century on remote Pitcairn Island, seemed to make a link with the old, pre-package tourism Norfolk, the Norfolk that Australia’s hostile take-over of the island’s governance will perhaps ultimately destroy.

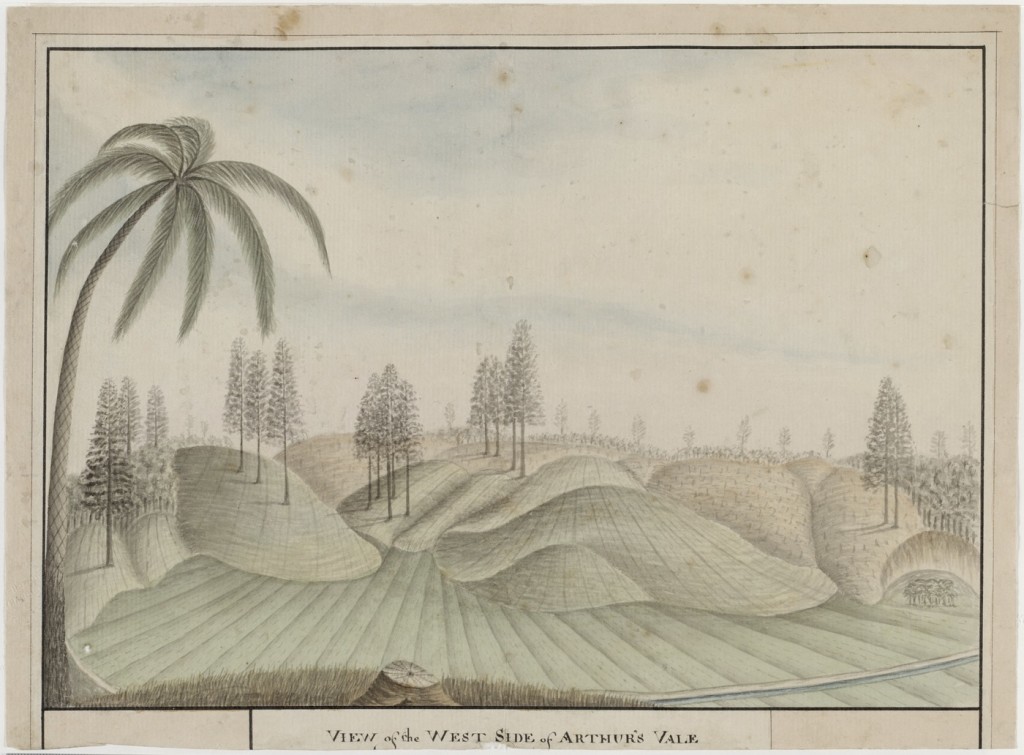

View of the west side of Arthur’s Vale, Norfolk Island, Sir Joseph Banks papers, cc. 1790s-1803 (Wikimedia Commons/State Library of NSW)

View of the west side of Arthur’s Vale, Norfolk Island, Sir Joseph Banks papers, cc. 1790s-1803 (Wikimedia Commons/State Library of NSW)

In closing the un-named MC acknowledged the Administrator’s generosity in opening nearby Government House to visitors for the traditional ‘Gunfire Breakfast’ – ‘gunfire’ being an inheritance from the British army’s traditional name for dawn in its cantonments – but the courtesy concealed a further clash in the ballet between island and Australia. The island’s RSL was holding a rival Gunfire Breakfast at the Golf Club, a few hundred metres away along Quality Row. The Administrator’s staff and RSL officials had for the past few days been trying to entice visiting tour groups to patronise one breakfast rather than the other.

The rival breakfasts struggle offers a reminder in miniature that Anzac Day is not a simple, timeless ceremony of remembrance. It clearly reflects the emotional needs of the communities which hold and celebrate it, but also the political, diplomatic and even economic imperatives of the nation – indeed nations – that sustain it. Perhaps the little ceremony at Emily Bay, Norfolk Island, gives us all the explanation we need for the strange survival of Anzac Day a hundred years on.

Professor Peter Stanley of UNSW Canberra, is President of Honest History. He has recently been identified by conservative columnist Miranda Devine (based on criticism by Dr Mervyn F. Bendle in his book Anzac and its Enemies) as an enemy of Anzac Day.

Peter Stanley here.

I received this message from a Norfolk Island resident:

Dear Dr Stanley

I have just read with interest your article published in Honest History about the Anzac Day Dawn Service at Emily Bay Norfolk Island. I was also there and I would like to congratulate you on your very insightful reportage of this event.

As trivial as it may be, I would also like to correct a small inaccuracy in your article where you comment on the origins of our Pitcairn Anthem.

You article states “The archaic words, composed in the early nineteenth century on remote Pitcairn Island, seemed to make a link with the old, pre-package tourism Norfolk, the Norfolk that Australia’s hostile take-over of the island’s governance will perhaps ultimately destroy.”

The Pitcairn Anthem (come ye blessed) was indeed put to music by Englishman George Hunn Nobbs and Pitcairn Islander Driver Christian sometime around the mid-19th century. However the lyrics are straight out of the Gospel of Matthew, chapter 25, verses 34-36 and 40 and therefore should be attributed to the good Apostle himself.

I believe the tune we sing on Norfolk differs to the tune sung by the inhabitants of Pitcairn Island today, however the fact it is sung on both islands suggest the musical origins of these verses may have commenced on Pitcairn Island prior to the relocation of the Pitcairners to Norfolk in 1856.

Your observation of the dearth in our singing nowadays is both unfortunate and correct. It is one element of life here now strangely at odds with our desire to preserve these aspects of our strong traditions and culture. If I had held a microphone equal to that of the MC Terrance Grube, then you might have heard my voice along with his. Albeit much flatter and out of key!

Best Wishes

Charles Christian-Bailey

Thank you, Charles!

Peter Stanley