‘Diggers doing time? Australian courts martial 1914-19’, Honest History, 30 April 2020

[Note: The authors are seeking help from volunteer citizen historians. See the endnote. HH]

From 1916, Anzac Day was commemorated to remember the fallen and honour those baptised by fire on the shores of Gallipoli. That same year, 1916, the Australian army conducted at least 3342 courts martial for military and civil infractions. The fighting spirit and resourcefulness of the Anzac has become legend; soldiers who broke the law have been swept to the margins of history.

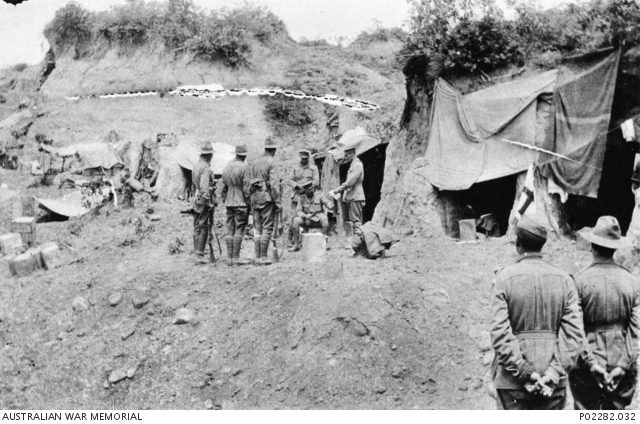

Major AJ Bennett, 3rd Battalion, conducts a court martial, Gallipoli 1915 (AWM)

Major AJ Bennett, 3rd Battalion, conducts a court martial, Gallipoli 1915 (AWM)

Australian soldiers during the Great War had a reputation for indifference to authority. Their apathy in the face of discipline warranted commentary and complaint among old-school English officers. The failure to salute senior officials in places like London’s Broadway or the Strand was a particular bugbear. But, even within their own ranks, Australian soldiers famously exhibited a certain familiarity. According to one popular story, a burly Queensland sentry offered little more than a casual glance to the commander of Australian troops, General Sir William Birdwood, on the frontline. Some choice language soon followed. ‘Duck your —- head, Birdie!’, the soldier yelled, as a shell came screaming overhead.

Beyond British mutterings of insubordination and anecdotes of cheeky Australian character, contemporary statistics revealed the reality of disciplinary problems among Australian troops: they were consistently much more likely to be prosecuted than British, New Zealand or Canadian soldiers. Whether rates of crime and indiscipline affected Australia’s overall military effectiveness, however, remains an open question.

Contemporary politicians and commanders were sure that the prohibition of the death penalty for Australian troops fuelled the problem. Diggers escaped the firing squad even when they were convicted for capital offences like mutiny, desertion, and treating with the enemy. The British made much of this exceptionalism. They pointed to its effect on the fighting efficacy of Australian divisions as well as discontent in other armies. Australian officers like Brigadier-General Henry Goddard agreed. He noted in 1917 that, ‘There is a growing impression amongst the men throughout the AIF that no actual punishment will be inflicted for desertion and all suspended sentences will be annulled at the end of the war’.

With the spectacle of the death penalty missing from the administration of Australian military justice, the topic has failed to spark interest among scholars or the public. The visible political campaigns in recent decades for retrospective pardons for executed British and other Dominion soldiers have little local traction.

Yet Australia has a remarkable story to tell, through its extraordinary record of over 22 000 courts martial held between 1914 and 1919. These files, transmitted from the field of battle into the custody of the Attorney-General, now sit in the National Archives of Australia. We recently analysed a (broadly representative) sample of 250 of these cases to see what they could tell us about the processes and outcomes of Australian discipline.

We found that the overwhelming majority of prosecutions (85 per cent) targetted the rank and file, mainly privates but including small numbers of troopers, sappers and drivers. Major offence categories included desertion and being absent without leave. Charges like disobeying orders, drunkenness and a range of criminal offences, including manslaughter, stealing and arson were less frequent. Perhaps unsurprisingly, officers fared better than their subordinates when matters came before a court martial. They were four times more likely than privates to be acquitted.

These patterns are replicated in the distribution of penalties. Desertion was a grave offence, with the death penalty sentence awarded against seven convicted men in our sample (with a total of 121 soldiers across the war), though never carried to execution. Other available sentences included shorter and longer terms of imprisonment up to life, detention and ‘field punishments’, and a reduction in rank or forfeiture of pay.

Half of the officers in our sample found guilty received a penalty of rank reduction, although that was sometimes quickly reversed. Two-thirds of privates convicted were sentenced to detention, field punishment or prison sentences. None of the capitally convicted soldiers was executed, in line with Australian government policy. Many others, especially those initially sentenced to long-term imprisonment, had their sentences commuted or suspended in one way or another.

Method of attachment to fixed object as required in Field Punishment No 1.: War Office, London, 1917 (AWM25 807/1)

Method of attachment to fixed object as required in Field Punishment No 1.: War Office, London, 1917 (AWM25 807/1)

The Australian Army was also exceptionally reluctant to impose the more severe Field Punishment 1, which involved binding men to a fixed object outdoors for up to two hours a day. According to our sample, the Army preferred the lesser penalty of Field Punishment 2 (without the exemplary humiliation of restraint in public view) by a factor of three to one. This finding is the inverse of the position in the entire British Expeditionary Force.

The files of military justice allow us to remember war in a different way. They shed light on a form of ‘Australianness’ forged not on the battlefield but in the corridors of power, where officials refused to implement the death penalty, in opposition to the demands of Imperial masters. A prosecution rate nearing one court martial for every 19 soldiers enlisted tells another story. It reveals the many infractions of those who we are so often told birthed modern Australia.

* Yorick Smaal is senior lecturer in history, School of Humanities, Languages and Social Science, Griffith University, and Deputy Director Harry Gentle Resource Centre. His book, Sex, Soldiers and the South Pacific: Queer Identities in Australia in the Second World War, was reviewed for Honest History by Diane Bell.

Mark Finnane is Professor of History, School of Humanities, Languages and Social Science, Griffith University.

A longer version of this article is to be published in Australian Historical Studies. This work was supported by Australian Research Council: [Grant Number FL130100050]; Griffith University [Grant Number Arts Education and Law Group Research Grant (2017)].

The National Archives of Australia has recently digitised the name index cards to these First World War files as well as other conflicts across the twentieth century. The Prosecution Project and its volunteer citizen historians are currently transcribing more than 90 000 name index cards for Australian courts martial. Click here to get involved.

For more on related subjects, see: Roger Beckett, ‘The Australian soldier in Britain, 1914–1918’, Carl Bridge, Robert Crawford & David Dunstan, ed., Australians in Britain: The Twentieth-Century Experience, Monash University ePress, Melbourne, 2009; Peter Stanley, Bad Characters: Sex, Crime, Mutiny and Murder and the Australian Imperial Force, Murdoch/Pier 9, Sydney, 2010.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.