Michael Piggott*

‘This Japanese internment camp diary is a gentle and innocent work from a dark time’, Honest History, 10 April 2022

Michael Piggott reviews Four Years in a Red Coat: The Loveday Internment Camp Diary of Miyakatsu Koike (translated by Hiroko Cockerill; edited with an introduction by Peter Monteath and Yuriko Nagata).

Diaries diaries everywhere …. It’s hard to avoid them at the moment. Everyone, it seems, is reading one of Chips Channon’s blockbuster diary volumes or watching The Andy Warhol Diaries on Netflix. And Anne Frank, probably the world’s best-known diarist, continues to make news as headlines earlier this year announced the discovery of her family’s betrayer – or perhaps not. Last year, Text released the third volume of Helen Garner’s diaries and, of course, throughout the pandemic lockdown, libraries, rarely before interested in collecting the everyday diaries of ‘ordinary’ Australians, have been encouraging and enabling us to record our responses, as Richard Neville wrote recently (pp. 23-25).

Indeed, it’s surprising that diaries published and unpublished aren’t taken more seriously in Australia as document and human product, or indeed as the focus of a research program within the academy – perhaps in the ANU’s National Centre for Biography? One does wonder where our equivalents are of Polly North and Irving Finkel in London.

Indeed, it’s surprising that diaries published and unpublished aren’t taken more seriously in Australia as document and human product, or indeed as the focus of a research program within the academy – perhaps in the ANU’s National Centre for Biography? One does wonder where our equivalents are of Polly North and Irving Finkel in London.

But I digress.

Miyakatsu Koike was an employee of the Yokohama Specie Bank, Surabaya, Dutch East Indies, from 1935 until late 1941 when, with the attack on Pearl Harbour in late 1941, he and many other Japanese from Java, Borneo and the Celebes were sent to the internment camp at Loveday in the Riverland area of South Australia. Koike’s wife had returned to Japan before hostilities commenced. In February 1946, with other Japanese civilians and POWs from other camps, Koike himself was repatriated.

In 1987, aged 82, Koike published a memoir of the Loveday experience, based on diary notes, plans of camp layouts, and some drawings by fellow internees. The memoir was essentially for his own and former bank employees’ families. Now, in 2022, it has been reissued in translation, together with an historical introduction, a note on the text, footnotes, and other editorial interventions. There are also additional illustrations from the Australian War Memorial, the International Committee of the Red Cross archives in Geneva, and the State Library of South Australia. All of these add considerably to the text.

Editing/categories

The idea of a ‘diary’ sits in the same territory as journal and log, while the latter in the online world has conjured variants such as weblog, vlog and blog. Essential, though, is the idea of an individual’s regular, typically daily, record of recent happenings, observations, appointments, thoughts and so on. It need hardly be said that the values of a contemporary record and of a memoir are different, though both demand careful handling by the historian in deriving evidence and by the archivist in documenting context and provenance. (Forgery requires both and more.) What Koike published was a mixture of contemporary notes, some quotidian, and recollections presumably drafted in the 1980s in preparation for publication.

The editors’ Note on the Text is slightly longer than a single page and they show about that much interest in what archivists would call record types or document forms. For example, they use ‘diary’ and ‘recollections’ interchangeably. But what is hard to overlook is the editors’ absence of comment about their documentary editing decisions. Their interventions are invisible, except for the use of curves and square brackets, where in time the reader realises which are the author’s and which the editors’.

As for a Translator’s Note, like an index, the editors (or someone) deemed it not needed. The translator, Hiroko Cockerill, has published widely on the challenges Japanese raises, however, and if allowed, might at least have explained how Koike’s 1987 title, Diary of Internment: Four-Year Life in Red Uniform became Internment Diary: Four Years Life in a Red Coat for the website Lovedaylives.com and now Four Years in a Red Coat?

Loveday Camp (Loveday Lives)

Value

What are we to make of this publication, and against what criteria? Wakefield Press emphasised in its blurb and media release that, for the first time in English, here now is Miyakatsu Koike’s wartime diary. The Editors’ Introduction, by two eminent scholars of Australian internment, explains much about the relevant historical context but sadly nothing about Japanese internment diaries and memoirs in general.

Is Koike’s memoir/diary highly significant as an historical source, perhaps supporting a rethink of historical orthodoxy in 1987 when it appeared? Aside from the obvious point that all unpublished diaries are by definition unique, is Koike’s rare? We do know from the 1993 doctoral thesis of one of the editors, Dr Yuriko Nagata, that, as well as Koike’s, at least one other diary was compiled in Loveday. (It resides with English translation on a file held by the National Archives of Australia, NAA: AP613/1, 90/1/101, a file bizarrely still in part restricted to the public.) And there are at least two other diaries, by Taishiro Mori and Miki Tsutsumi, who were interned at Tatura. In content and affect, were they largely similar to Koike’s? Are there extant Japanese internees’ diaries surviving from Featherston, Pahiatua and Somes Island in New Zealand to allow comparisons?

Overall

There is a gentleness and innocence in this work. In the diary sections the one-line entries repeatedly mention weather and food, anniversaries and entertainment, news from home and who died this week – the effect elevating it to the universal everyday concerns of humankind despite its carceral context: ‘Today I darned my socks using a needle. I realised how much I rely on my wife’ (26 May 1942); ‘I was on basin cleaning duty’ (21 September 1942); ‘We enjoyed tomatoes grown in the camp vegetable garden’ (4 February 1943); ‘Fine. We had our first frost’ (17 May 1944). One almost expects a Pepysian, ‘And so to bed’.

More specifically, the value of Koike’s text derives from its role as a reminder that, in war, everyone – civilians as well as soldiers, diaspora as well as the home populations – is caught. No one is unaffected, at the time and long afterwards. The memoir/diary was written by an old man for a sympathetic audience still loyal to motherland and emperor and it tracks not only his own deprivations and determination to cope, not only an internee’s view of Australian camp behaviour, but also his gradual acceptance that Japan was being and then was indeed defeated and devastated by the ‘war without mercy’. This may just help us see beyond the understandable if simplistic juxtaposing of Allied treatment of civilians and POWs versus that by Japan, recalling one of the values of Sarah Kovner’s new study Prisoners of the Empire, so insightfully reviewed in the current Australian Book Review by Joan Beaumont.

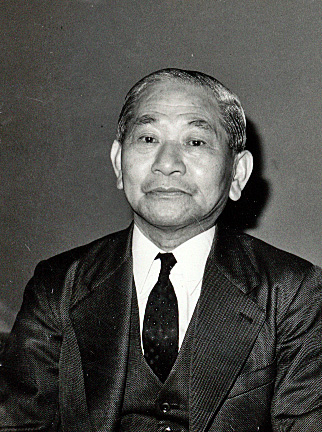

Miyakatsu Koike in later life (Loveday Lives/Koike family)

Conclusion

In his preface dated November 1987, Koike wrote of his book, ‘I hope that it will help children to understand the misery caused by the war and the importance of peace’. In their Acknowledgements, the editors hoped that Four Years in A Red Coat would ‘expand our understanding of the civilian internment experience in Australia during World War II through the words of a Japanese internee who spent four years behind the barbed wire at Loveday’. I hope so too and suspect that those who read the diary will gain a larger appreciation of the human spirit.

* Michael Piggott AM is a retired archivist whose interest in diaries began when he was working on the CEW Bean papers at the Australian War Memorial many decades ago and more recently has led to conference papers, scholarly articles and a curated exhibition, ‘Inscribing the Daily’, at the Baillieu Library. He has written many reviews and other pieces for Honest History: use our Search engine or References by author.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.