Michael Piggott*

‘Pompey Elliott’s war reporting, letters and diaries reveal a complex man and soldier’, Honest History, 25 October 2017

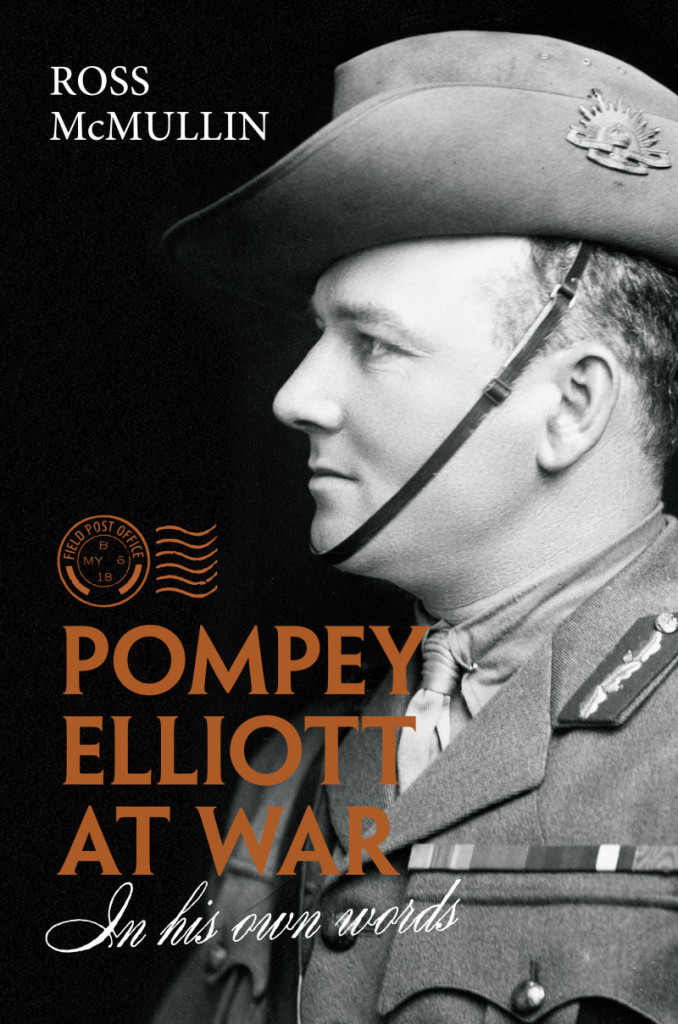

Michael Piggott reviews Pompey Elliott at War: In His Own Words

Fifteen years ago, Ross McMullin published his massive and much praised biography of Major General HE (Pompey) Elliott. Now we have Pompey Elliott at War: In His Own Words, a compilation of Elliott’s words direct from letters, diaries and official records (war diaries, reports, orders, cables, etc.) together with some contemporary reports of his speeches. This is indeed a review of that new volume, but I want to begin by briefly mentioning two classic approaches to information management: pre- and post-coordinated indexing.

Pre-coordination is the combining of subject terms attached to an information resource into one compound term which anticipates a search for a very specific topic, for example, women red wine makers in 21st century Australia. Post-coordination, on the other hand, assumes single subject terms are attached to information resources (for example, women, wine-making, wine) and leaves the searcher to combine terms to suit a future subject interest. Think of two sandwich bar options for lunch, one which anticipates requests by having pre-prepared combinations, such as a wholemeal bread containing bacon, tomato, lettuce and mayonnaise, while the other has ingredients ready, then leaves it up to you to mix and match.

Pre-coordination is the combining of subject terms attached to an information resource into one compound term which anticipates a search for a very specific topic, for example, women red wine makers in 21st century Australia. Post-coordination, on the other hand, assumes single subject terms are attached to information resources (for example, women, wine-making, wine) and leaves the searcher to combine terms to suit a future subject interest. Think of two sandwich bar options for lunch, one which anticipates requests by having pre-prepared combinations, such as a wholemeal bread containing bacon, tomato, lettuce and mayonnaise, while the other has ingredients ready, then leaves it up to you to mix and match.

For his biography McMullin pre-coordinated – we might say pre-digested – a huge quantity of Elliott material and other primary and secondary sources and combined these ingredients into a compelling narrative of a life (1878-1931), though the book started with Elliott’s grandparents and ended with his children’s deaths, the daughter’s in 1971. In this new work under review, we are offered extracts from 1105 of the key sources themselves. Don Watson did something similar with The Bush: Travels in the Heart of Australia (2014), followed up by the companion volume A Single Tree: Voices from the Bush (2016). In McMullin’s companion compilation, the sources are consciously selected and deliberately arranged chronologically covering August 1914-January 1919, although we too are free to ‘post-coordinate’ them, to draw on them to suit our own interests.

First, however, we should consider the compiler-editor’s interests. In the late 1970s, McMullin identified Elliott as singularly significant in the pantheon of Australian World War I identities, and 40 years later the superlatives endure. In the Introduction to Pompey Elliott at War, McMullin wrote, ‘No Australian general was more revered by those he led or more famous outside his own command’ (p. 1), and ended the Epilogue with the observation that ‘Australians influenced the destiny of the world in 1918 more than any other year before or since, and Pompey Elliott was front and centre in this climax of the conflict’ (p. 492).

There had been earlier superlatives, if now largely forgotten, like those by Alec Hill in his Australian Dictionary of Biography entry (‘his grasp of the situation and capacity for quick, decisive action was supreme’), Monash (on Elliott’s Villers-Bretonneux counterattack: ‘the finest thing yet done in the war by Australians’), Serle in his Monash biography (‘one of the AIF’s greatest aggressive commanders who also most considered his men’s protections’) and CEW Bean in the Official History (Elliott’s ‘unrivalled hold … on the loyalty of his men’). Now in the new century, thanks to Henry Rosenbloom at Scribe, a small group of supporters in Ballarat and elsewhere, and the war centenary, a new readership can learn of an exceptional military leader and larger-than-life personality.

Although Elliott’s many commendable qualities were there early, and palpable in his pre-war years at the University of Melbourne, in the Boer War and at the Bar, the four years of the Great War made (and tragically un-made) him. Thus the narrow but understandable focus of Pompey Elliott at War. Through the book’s 25 chronological chapters, McMullin’s quick introductions to the quotes and occasional footnotes deftly present Elliott’s own recorded experience of Gallipoli, the Western Front (and occasionally Egypt, England and Scotland).

This was quite a time for Elliott, as a battalion then brigade commander: fighting, recovering from and preparing for action; taking care in appointing officers; organising, liaising, rallying, arguing, getting wounded; helping read and planning to counter the enemy’s intents. All the time he was pouring his heart out to his wife, venting frustration in diary entries and in official reports, too, getting angry at ill-discipline, weakness and lack of appropriate recognition, exulting in enemy defeats and his men’s victories, and reacting in equal measure to deaths and death.

Elliott as a Brigadier-General (National Anzac Centre)

Elliott as a Brigadier-General (National Anzac Centre)

Secondly, the 1105 excerpts in Pompey Elliott at War allow us to rearrange the documents to suit other themes of interest. Here the letters Elliott sent to his wife and children come into their own, their importance already reflected on by McMullin in the introduction and, in relation to the children, in his lecture ‘Vigour, rigour and charisma: the remarkable Pompey Elliott, soldier and senator’ in a Senate series in 2002.

I suspect that the Elliott letters would be unrivalled as a resource for a case study of an Australian marriage in early 20th century Australia. They convey deeply expressed longing, grief, anger and the rest. Separation and the real possibility of death can indeed prompt heartfelt frankness. One gets the added impression that Elliott never stopped believing his luck when Catherine Campbell agreed to marry him in 1909 – a union which resulted in two delightful healthy children – and this triple-A alpha male, anything but the taciturn Aussie, put it all down on paper.

Of course, it did take war to bring the letters into existence, and wife and daughter to cherish then release them to the Australian War Memorial and now Ross McMullin to commit them to posterity. The War and Emotions people within the Centre of Excellence for the History of Emotions would know exactly how to re-mine them.

***

As a print publication, the volume has few flaws. The copy editing is of a high standard. The illustrations support the text. Physically it handles well and is bound properly; opened in the middle, it sits flat. Only the index left me occasionally confused; for example, the way terms were ordered under Elliott’s name was not obvious or easy to use. Finally, some individuals mentioned only by surname in letters and reports lacked editorial elaboration and were left incomplete in the index.

As case in point is ‘Capt Street’(text) but ‘Street, Maj.’(index), the replacement Brigade Major foisted on Elliott in 1917 and mentioned almost a dozen times by Elliott or McMullin. The relationship was a failure, ending in April 1918 when Street mis-communicated orders, a blunder discovered and corrected only just in time and which could have resulted in ‘a massacre’ (p. 356). By cross-checking with the biography, we learn this man was GA Street. So he must have been the same Street the now Senator Elliott alluded to in April 1921 during a debate on the Air Defence Bill; Elliott referred to a wealthy ‘social butterfly’ who ‘could not sleep in anything rougher than silk pyjamas at ten guineas a suit’. This was also the Street who became Minister for the Army and perished in an air crash near Canberra in August 1940.

***

As final thoughts, I want first to consider again the sources which support this book. Because Elliott was such a diligent, expressive and honest diarist, correspondent and report writer, this gathering of pure grade historical evidence captures his character in some senses better than any biographical estimate, though the sources enabled such estimates too. Indeed, as McMullin has explained in the Introduction and elsewhere, it was the existence and richness of the sources which first stimulated the idea of a biography.

Just less than 50 per cent of Pompey Elliott at War comprises letters to wife Catherine (‘Kate’). These brim with highly descriptive war reporting and phrases which nail a character (‘Genl Plumer … is a funny little fat red-faced man, very white hair and moustache – but he is a good general. He said he was pleased with my boys …’ p. 274). The letters are also intensely personal, some almost too personal to comfortably read. Obviously, however, this was not one- way communication. Elliott longed for letters from home, and exulted when a parcel of them, at times with photos (p. 107), arrived safely.

Cigarette card with The Argus, 1919 (EmpireCall/PBWorks)

Cigarette card with The Argus, 1919 (EmpireCall/PBWorks)

Where then is the soul mate’s voice? We can glean some of what was conveyed when Elliott replies to specific points, but what Kate wrote we cannot know, because, periodically during the war, her letters were destroyed. In a letter to Kate dated 11 November 1917, Elliott wrote that ‘I’d like to keep all your letters but I cannot carry them. I am always sad when I have to burn them’ (p. 315). Given how much Pompey must have treasured Kate’s letters the deliberate loss is hard to fully understand. Couldn’t he have arranged for their safe storage – given the bureaucratic resources at the disposal of such a senior officer – or sent them back once read? Was privacy a subconscious factor?

He recorded many other letters being received too, including from his sister-in-law, his children, Melbourne friends and former legal colleagues. Where are they? In the main collection of his papers at the War Memorial (2DRL531), there is but a solitary wallet (3/16) of letters to Elliott (‘from various family members’, 1913-1929).

In fact, collectively, what did become of the letters sent by families to their loved ones at the front? Many letters would have been lost or destroyed through the contingencies of fighting. Some may have trickled back via the AIF Kit Store, London, to Australia as part of deceased missing and captured soldiers’ personal effects. But, as far as I know, no one was diligently collecting originals (or copies, assuming correspondents from home kept them) to help the official historian, and the focus of collecting by libraries and archives has always been on letters and diaries by not to soldiers, something I need to plead guilty of myself as an archivist.

The historical value of letters to men and women at the front needs no justification now, as the use of those letters which survived the war and were kept shows. Joy Damousi’s references in The Labour of Loss to letters from Alfred Derham’s sister, mother and fiancée are a case in point. In The Broken Years, Bill Gammage wrote of the soldiers’ letters and diaries he researched that, aside from the inevitable privileging of those who, in war or peace, tended to write, over those who didn’t, ‘I believe no significant bias exists in the records’. But here we surely have a large biased absence. Is it in fact, as WEH Stanner put it in his famous Boyer Lectures, ‘a structural matter’, another ‘Great Australian silence’?

Lastly, there is the tragic nature of Elliott’s death in March 1931 by his own hand, then and for much of the remaining century considered a shameful way to die. A sense of injustice at missed promotions had dogged him during the war, exacerbated not only by his low opinion of both the key decision-makers (especially Birdwood) and those preferred ahead of him, but also by his failure ever to obtain explanations which satisfied his logic or contradicted his suspicions. This issue of ‘supersession’ ate away at Elliott into the 1920s and was never assuaged by numerous other acknowledgments, honours and achievements.

The penultimate chapter of McMullin’s biography powerfully relates Elliott’s tragic disintegration, but there is enough in his new book quoting his official and personal wartime letters to gauge the degree of anger and its repeated injudicious and counterproductive expression. Other worries, mostly connected with the Depression, also played their part. Elliott loved his men and their loyalty to comrades and unit colours, became distraught at their disfigurement and slaughter, and hated the fact that he couldn’t adequately protect them during the war nor properly help returned men during the late 1920s.

Elliott and wolf cubs, after the war (Grand Pacific Tours)

Elliott and wolf cubs, after the war (Grand Pacific Tours)

In the biography, McMullin suggests, without pushing the point, that Elliott was suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. PTSD-related suicide is no longer a barrier to inclusion on the Australian War Memorial’s Roll of Honour. The war undoubtedly caused Elliott’s death; it just took a decade longer than the Memorial’s cut-off date for inclusion of such deaths on the Roll.

In McMullin’s fine compilation there is also evidence to ‘post-coordinate’ an alternate interpretation of Elliott’s slow demise. Perhaps he was his own worst enemy, stubbornly refusing to listen to the advice of colleagues and the occasional sympathetic superior to temper his language (or at least not commit it so often to paper) and stop needlessly antagonising those who could harm him. Buy Pompey Elliott at War and see what you think.

* Michael Piggott AM is Honest History’s Treasurer and holds a number of other positions in Canberra. He has written often for the Honest History website. The Honest History Book includes a chapter from Michael on how Charles Bean has been used during the 75 years’ history of the Australian War Memorial.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.