Michael Piggott*

‘Mouldering away: how long a journey for our National Archives?’, Honest History, 16 June 2021

[See also this post on the campaign to save the Archives. HH]

As many Honest History supporters will know, in recent months the media has published and broadcast stories supporting improved funding for the National Archives of Australia (NAA). The champions have included academic historians Michelle Arrow and Frank Bongiorno (The Drum, Canberra Times), journalist Paul Daley (The Guardian) and writer and commentator Gideon Haigh (The Australian). Bodies such as the Australian Academy of the Humanities and the Australian Society of Archivists have issued statements.

As well, David Fricker, the Archives’ Director-General, already known through the ‘Palace Letters’ court cases, has enjoyed favourable coverage highlighting the urgent need to preserve rapidly deteriorating audio-visual records, though he has been publicising urgent preservation needs for several years.[1] Behind this topicality is a review into the NAA by David Tune, a retired Finance Secretary, and one of his 20 recommendations in particular, that the Archives receive $67.7m of extra funding over seven years for the ‘digitisation of the high priority (at-risk) records’.[2]

In the past, archives reviews have been led by a senior official from the Prime Minister’s Department (AL Moore in 1964) an eminent Canadian archivist (Dr W. Kaye Lamb in 1973) and the Public Service Board (AR Begbie and RJ Minns in 1981). There have been legislation reviews (the Archives Bill, late 1970s; the 1983 Act, late 1990s). Now, reviews focus on ‘efficiency’, a Don Watson weasel word[3] the Tune report uses repeatedly. Thus: ‘Over the past 5 years, the National Archives has absorbed the budget efficiency and savings measures, finding efficiencies in its operations through reforms, down-scaling of services and improved management of its leasing and storage arrangements, and reduction in staffing levels through multiple voluntary redundancy programs (p. 10)’. Indeed, NAA staffing fell from 470 in 2012 to 384 in 2018, and by closer to 25 per cent if we bring the period up to 2021.

The Tune review was set up in early 2019; the reasons why are not publicly known. We can assume they were not as benign or instrumental as the Archives’ own rationalisation on its website, which began, ‘In recognition of these significant challenges and opportunities, in 2019 the Australian Government initiated …’. Tune himself stated that his aim was to:

consider and make recommendations on the enduring role of the NAA in the protection, preservation and use of Commonwealth information; how the NAA might best perform this role; and what powers, functions, resources, and legislative and governance frameworks the NAA needs to effectively and efficiently undertake this role in the digital age (p. 20).

Reviews and inquiries usually include tactical political motives, sometimes even the motives of the target agency. I happen to know that, when Finance was circling the Archives in the late 1990s, a successful invitation from the Archives to the Australian Law Reform Commission to review the Archives’ 1983 legislation saw the threat at least temporarily disappear. With Tune, some of the context is clear, and includes representations in 2018 from the Archives Advisory Council to the Attorney-General about improved funding and updated legislation.

School visitors to the Archives (NAA)

Now, these are not new issues and there seems little urgency beyond funding. Politically, of course, reviews buy time. And when the report is submitted, one needs to consider the recommendations – carefully, and fully, consider them, and indeed, consult further – so as to reassure powerful interests (aka ‘key stakeholders’). With the Tune review, completed in January 2020, it took another 14 months and an FOI request by Senator Patrick, to force the report to be made public.

Once it became public, the report was disingenuously welcomed with all the right words by the relevant Minister, Senator Amanda Stoker, in a statement where she confided, ‘I look forward to working with the National Archives, the experts and all the stakeholders as we continue this journey’.[4] And the government’s response? At what point along the journey will that be issued? In a Senate Estimates hearing on 27 May 2021, the Minister said, ‘I don’t expect it’s an awfully long way away, but I won’t give you a precise date’. When Senator Raff Ciccone asked, ‘Are we expecting a response this year?’, she answered cryptically, ‘Yes’.[5]

***

In the same month that Senator Stoker was being quizzed in Parliament, the government’s 2020-21 Budget was announced. It left NAA on basic rations, with none of the additional funding recommended by Tune. The Archives had received one-off funding in the past (for example, to start digitising 850 000 Second World War personal service files[6]), but the cruel so-called efficiency dividend remained. In response, NAA redoubled efforts to publicise the case for better government funding and launched an appeal for donations, having formed a members’ group earlier in the year. We wish it well but, as this is new territory for the Archives, it will need to think about three issues.

1. Clarity of role and message

For decades, most if not all of the national cultural institutions have been grouped for portfolio and policy purposes under ‘arts’, a combination of supporting literature, performing arts, and bodies like the Australia Council, plus what is increasingly grouped as ‘the GLAM sector’. Currently, for example the library, gallery, portrait gallery, museum, maritime museum, democracy museum, and the film and sound archive all come under the Office for the Arts,[7] part of Minister Paul Fletcher’s Communications, Urban Infrastructure, Cities and the Arts portfolio.

Campaign to save the Archives: publicity (ArtsHub)

Campaign to save the Archives: publicity (ArtsHub)

By contrast with those institutions, the Archives is part of Attorney-General’s, the Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies is part of Prime Minister and Cabinet, and the Australian War Memorial is part of Veterans’ Affairs. Yet these last three also preserve parts of Australia’s cultural heritage, are part of the memory of the national and help tell the Australian story.

Since archives was separated from libraries, government has never had a settled idea how to categorise archives as an administrative function and portfolio responsibility. In 1961, the Commonwealth Archives Office (CAO) was established apart from its parent the National Library, and the Archives has since been moved between dozens of ministries, with two broad functions predominating – arts/cultural heritage and administration/finance. The CAO started 60 years ago as part of Prime Minister’s and has been with Attorney-General’s since Tony Abbott’s victory in September 2013. Nevertheless, for some arts programs, such as the National Collecting Institutions Touring and Outreach (NCITO) Program, NAA is considered an arts agency.

Of course, as is obvious from its 1983 legislation, the Archives has essentially two roles, a cultural heritage/memory of the nation role and a government recordkeeping role. In recent decades, the Archives has deliberately chosen to expand this second role to embrace information management and cyber resilience. Some people see this as necessary, given digital ubiquity and the collapsed boundary between ’record’ and ‘information’; others see it as a professional failure and mission creep doomed to failure. Tune devoted an entire chapter to the issue of the Archives’ role, and because a large number of agencies have responsibility for different aspects of information management, he discerned ‘a lack of clarity about requirements for information management in government and confusion about which agency is responsible’ (p. 33).

Does the public see things more clearly? For some national cultural institutions, it is relatively simple: war, maritime history, democracy, portraits, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander history, audio-visual content. These are strong tropes, easy to ‘get’, and they align with large reasonably easily identified constituencies. By contrast, the Archives’ funding appeal had a save-cultural-heritage hook and, in listing examples of at-risk audio-visual records, mentioned CSIRO experiments, nuclear tests at Maralinga, ASIO surveillance vision, audio-logs recorded by special forces soldiers in World War II, and rare audiotapes of Indigenous languages.

The NAA is the repository of massive numbers of Australian war service records (Aboutregional)

The NAA is the repository of massive numbers of Australian war service records (Aboutregional)

The messaging challenge, though, is to identify a strong emotional tie with an audience segment, preferably one politicians can’t easily ignore. Does the loss of old degrading government records make the cut? In the media and at Estimates, Minister Stoker downplayed the alarm, saying it is just part of the ‘ageing process’ because ‘time marches on, and all sources degrade over time’. Archivists have struggled for 50 years hunting for killer marketing angles and communication strategies, having learnt the dot points reposing in theory and, since 2010, enshrined in the Universal Declaration on Archives endorsed by UNESCO.[8]

Now the Archives needs what the authors of What Matters? called parables of value, well-chosen meaningful anecdotes or narratives, free of abstract data, which illuminate what is at stake in human terms.[9] It never hurts to have some compelling and current case studies either, along the lines of those compiled years ago by Horton and Lewis and now complemented by Moss and Thomas.[10]

2. Public campaigns

Of course, unless political campaigning is backed with a clear idea of what will constitute success, arguments alone rarely carry the day. The last time serious efforts were made to change government thinking about archives was the ‘Save the Census’ movement of the 1990s and it wasn’t being led by the Archives! There were several reasons for that campaign’s success,[11] but the arguments were backed by targeted political campaigning petitioning and lobbying. The users of archives in this case were not a handful of usual suspect high profile historians from the academy but over one thousand genealogy and local historical societies in every electorate, amounting to roughly 300 000 members across Australia.

For a cultural institution to lead a campaign for improved government funding is risky. The National Library managed it in 2016 to achieve increased funding for Trove, exploiting several cultural and legal advantages not available to the Archives. It was less comfortable tolerating the highly successful and innovative ‘Last Film Search/Nitrate Won’t Wait’ campaign bankrolled by Kodak and led by the irrepressible Michael Cordell.[12] This was in the early 1980s, just before the Library lost its film archiving role to a new National Film and Sound Archive.

It remains to be seen whether the NAA crowdfunding initiative meets a dollar target to equate to a ‘success’. The Minister at Estimates was not at all embarrassed by it but, on the contrary, full of praise. Still, if it is a stunt intended to shock, it has already succeeded to a degree, making news locally and London and New York[13].

Some people, of course, will say they are already financially supporting other cultural heritage preservation. Indeed, each national institution has a donate button and a number of them – as the National Portrait Gallery did last week – make an annual appeal as the tax year ends.[14] A few folks might think it a cheek, however, including those who have had to wait years for requested records to be declassified and who recall the Palace Letters campaign and the complaint the Archives Director-General is reported to have made to Jenny Hocking about the money he had to spend to defend restricting them: ‘It’s really eating into my budget’.[15]

3. Stakeholders, constituencies and champions

Who makes up the NAA’s ‘market’?

- All Australians is the technically correct answer, as we are a parliamentary democracy with systems of rights, entitlements, and accountabilities. Or we might say the nation, as in ‘the memory of the nation’, to quote the title of NAA’s 2007 corporate history.[16]

- Or we might say the taxpayer, given the costly consequences of poor recordkeeping, so regularly documented by Auditor-General’s reports and the savings inherent in, say, a good national health record system or indeed a system which can record during a pandemic who’s been where and when.

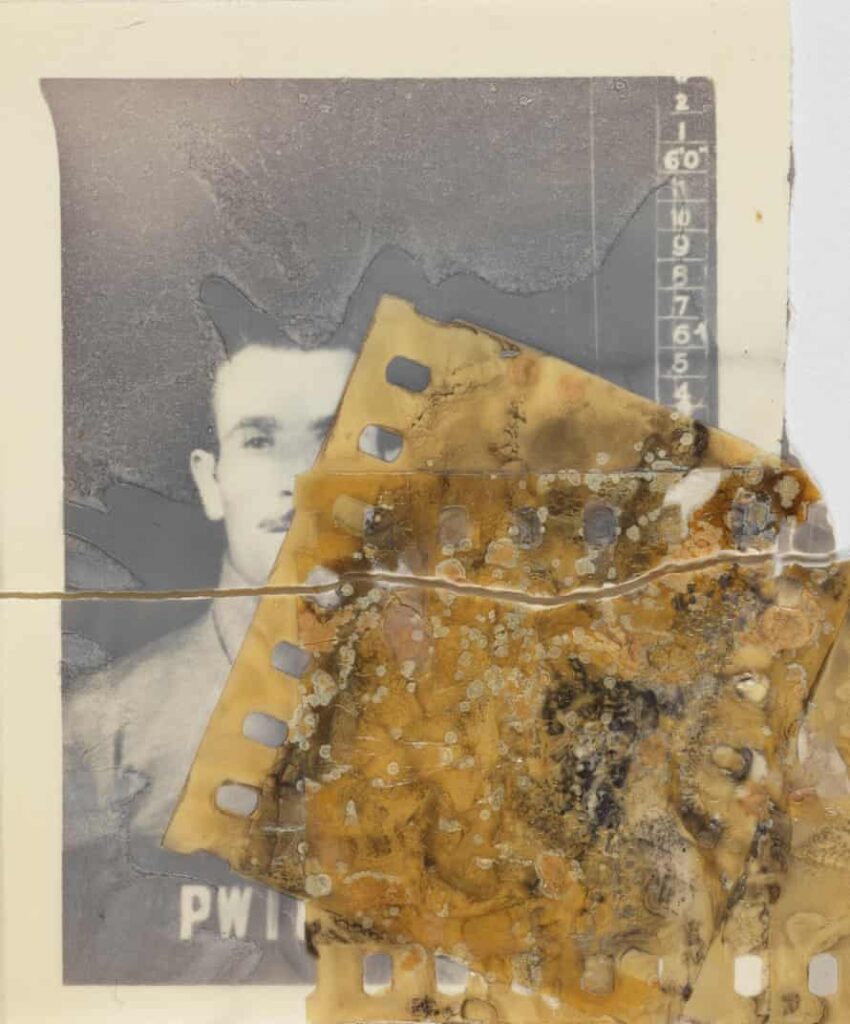

Deteriorating war records (Guardian Australia/NAA)

A more grounded response, however, notes four audience segments.

A more grounded response, however, notes four audience segments.

- First, there are those millions of citizens and non-citizens alike who through interactions with departments and agencies – and their portals, agents and algorithms – benefit directly because, ultimately, they and their mechanisms of accountability review and redress are reliant on proper recordkeeping systems (just as aviation systems need black box flight recorders).

- Secondly, there are all those who benefit indirectly because social systems work, and work in part because their safe and efficient functioning is underpinned by Commonwealth regulations, compliance standards, protocols etc., which in turn depend on the ‘social glue’ of recordkeeping.

- Thirdly, there are the tens of thousands of official and public users of Commonwealth records young and old; not just historians – academic, official, family, and other – but a list, even if in the hundreds, which can still suggest market categories, just as can the Archives’ own curators.

- And lastly, there are the secondary consumers and beneficiaries of these myriad uses and users, ranging from people who enjoyed an archives-based history book, podcast, documentary, or exhibition, to families finding some kind of closure from a Royal Commission or a cold case resolved.

Ironically, then, the Archives is spoilt for choice if not specificity. The Tune review recommended the NAA ‘[i]ncrease its marketing and program budget so it can better reach targeted markets’ (p. 14) but didn’t name these markets. Just as blithely, in Estimates, Senator Stoker, enthusing about marketing philanthropy and new income-generating ideas, said, ‘It’s about buy-in from the public. It’s about public engagement. It’s about active citizenship, by participating and understanding what the archives do.’

A second irony emerges when we ask where the Archives’ Advisory Council, the Archives officially designated champion, fits? The National Archives is an authority established by legislation, and its Director-General has specified powers but, unlike other cultural institutions, it is not governed by a council but responsible direct to government.

The NAA does, however, have an advisory council, with a statutory role readily allowing for representation and advocacy. Sadly, this body will only be as effective as its membership, of whom eleven are appointed by the Minister, just two by Parliament. One of the latter, Senator Kim Carr (ALP, Vic.), revealed at Estimates that the government seems in no hurry to fill Council vacancies, currently running at about one-third of the membership allowed for in legislation. Sadly too, governments think twice before appointing a chair who is assertive, vocal and very well connected. We have certainly heard of Kerry Stokes; who is Denver Beanland?[17]

***

Deteriorating records (Guardian Australia/NAA)

Deteriorating records (Guardian Australia/NAA)

What then of the future? Unless there is a genuine and widespread groundswell of public support for the Archives, matched by tens of thousands of memberships and millions of dollars donated by the public, unless the Archives can hold the media’s attention, and unless some government backbenchers and independent senators become seriously agitated, my fear is the Morrison government will see off this momentary agitation. After all, it has a national health emergency, a fragile economy, and strategic security challenges to face.

Meanwhile, Senator Stoker can wait for an election to be called, wait for David Fricker’s second five-year term to end on 30 December 2021, and perhaps even anticipate a new portfolio. The doomsday deadline for the magnetic audiotapes is still four years away. To implement all the Tune review recommendations was costed at $217 million. Perhaps Tune will be quietly shelved without official response, just as was the 2019 inquiry into Canberra’s national institutions.[18]

My worst-case nightmare dreads the opposite of inaction. In this scenario, the government actually responds to the Tune report, starting with recommendation 19, and indeed develops ‘a statement of expectations … outlining areas of government interest and priorities’. Then it adopts all Tune’s revenue raising and cost cutting ideas, including having Archives increase and expand fees, and require an aggressive philanthropic and fundraising program, despite Howarth Consulting’s findings, quoted by Tune, that such programs ‘absorb between 20 to 25 per cent of an organisation’s income for overhead costs’ (p. 72).

And, crowning it all, something equivalent to ‘a new chapter’, the Foreign Minister’s chilling description of our new relationship with Kabul.[19] In her Estimates evidence, Senator Stoker spoke of ‘the new system’ and foreshadowed ‘a new way of keeping records’.

Finally, my optimistic hope is that the faith the government has shown in experts during the pandemic is extended to its archivists. The experts are saying parts of NAA’s important collections are disappearing, but not only that. They are also saying it is more than a $67 million problem: there are issues at the top of the recordkeeping food chain as well as issues of access to and preservation of archives below.

The Archives’ legislation predates the internet, its declassification process is too slow, its influence over the bureaucracy’s recordkeeping is weak, and its staff numbers are being bled. The 2019 national institutions inquiry, led by the Prime Minister’s close ally and assistant minister, Ben Morton, noted that ‘the Archives holds Australian governments accountable to the people they serve’ (p. 9). Can there be anything more important?

The funds can be found. John Howard has said, ‘I fully accept that Australians will have different opinions of my government’s performance and of my leadership, but these views and assessments will be more compelling and persuasive when based on public records as well as media reporting and political commentary’.[20] But public records don’t look after themselves, though they do look after the people. My hope is that the people’s servants will do the right thing.

Deteriorating records (Guardian Australia/NAA)

* Michael Piggott AM is a semi-retired archivist with many years’ experience and has been Chair of the (ACT) Territory Records Advisory Council. He has a chapter in The Honest History Book. In 2020, he contributed chapters to Community Archives, Community Spaces: Heritage, Memory and Identity (Bastian & Flinn, ed., Facet, 2020) and “All Shook Up”: The Archival Legacy of Terry Cook (SAA & ACA) and wrote the Australian chapter in Archival Silences, edited by Moss and Thomas. He has written many book reviews and other pieces for Honest History (use our Search engine), including a review of I Wonder: The Life and Work of Ken Inglis, edited by Peter Browne and Seumas Spark.

[1] ABC TV 7.30, 19 June 2019 https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-06-19/magnetic-archives-at-risk-due-to-machine-becoming-obsolete/11222602

[2] https://www.ag.gov.au/rights-and-protections/publications/tune-review

[3] Don Watson, Watson’s Dictionary of Weasel Words, Contemporary Cliches, Cant & Management Jargon, Knopf, New York, 2004, p,.113.

[4] https://am.ag.gov.au/media/media-releases/government-releases-review-national-archives-18-march-2021

[5] https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;db=COMMITTEES;id=committees%2Festimate%2F261690c8-a36e-404d-a152-ef77d73ed688%2F0011;query=Id%3A%22committees%2Festimate%2F261690c8-a36e-404d-a152-ef77d73ed688%2F0001%22

[6] https://www.naa.gov.au/explore-collection/defence-and-war-service-records/digitising-world-war-ii-service-records

[8] https://www.ica.org/en/universal-declaration-archives

[9] Julian Meyrick, Robert Phiddian & Tully Barnett, What Matters? Talking Value in Australian Culture, Monash University Publishing, Melbourne, 2018.

[10] Forest Horton & Dennis Lewis, Great Information Disasters: Twelve Prime Examples of How Information Mismanagement led to Human Misery, Political Misfortune, and Business Failure, Aslib, London, 1991; Michael Moss & David Thomas, ed., Do Archives have Value? Facet, London, 2019.

[11] https://affho.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Mutch.pdf

[12] https://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-10-10/on-the-road—the-unreel–journey-to-preserve-australias-film/5804130

[13] Yan Zhuang, ’The guardians of Australia’s memory try crowdfunding,’ New York Times, 6 June 2021.

[14] https://www.portrait.gov.au/annualappeal.php?suggested=large

[15] Frank Bongiorno, ‘The wait of history,’ Canberra Times, 7 May 2021.

[16] https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/Record/4350597

[17] He is the chair of the NAA Advisory Council.

[18] Telling Australia’s Story – and Why It’s Important: Report on the Inquiry into Canberra’s National Institutions, Joint Standing Committee on the National Capital and External Territories April 2019 (Chair: Ben Morton MP).

[19] https://www.foreignminister.gov.au/minister/marise-payne/media-release/statement-visit-afghanistan

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.