Rod Olsen reviews Douglas Newton’s Hell-Bent: Australia’s Leap into the Great War

‘War is nothing but a continuation of politics with the admixture of other means.’ (Clausewitz)

‘War is unlike life … It’s a denial of everything you learn life is. And that’s why when you get finished with it, you see that it offers no lessons that can’t be learned better in civilian life.”[1]

_____________________________

Douglas Newton has made a very timely and extremely important contribution to our understanding of how Australia came to be a combatant in 1914. Newton states bluntly that Australia’s involvement was inevitable, given its place and status within the then British Empire, but he poses a series of thought-provoking, even provocative, questions to readers including:

What if Australia offered troops and its new navy to the United Kingdom unconditionally and at Australia’s expense, even before the British Government had decided to enter the war?

What if Australia’s offer of troops was made as the British Cabinet was split between neutralists and interventionists over the need at all for Britain to intervene in a continental war?

Newton answers these questions over the next 255 pages by means of deep research and analysis, evidenced in 68 pages of detailed footnotes and five pages detailing the particular archival and other primary sources he accessed in producing such an illuminating work.

Although I am only an amateur historian I thought I had a reasonable understanding of the outbreak of the Great War. Anyone who studied Modern History at high school in New South Wales in the 1950s and early 1960s invariably had the same question in the Leaving Certificate examinations, along the lines of ‘”Europe was a powder keg in 1914 and Sarajevo lit the spark.“ Discuss the causes of World War I.’

Prime Minister Joseph Cook and new Governor-General Munro Ferguson, St Kilda Pier, Melbourne, on Munro Ferguson’s arrival in the then federal capital to be sworn in, 18 May 1914 (State Library of Victoria; the information accompanying the photograph is incorrect but details can be gleaned from the press)

Prime Minister Joseph Cook and new Governor-General Munro Ferguson, St Kilda Pier, Melbourne, on Munro Ferguson’s arrival in the then federal capital to be sworn in, 18 May 1914 (State Library of Victoria; the information accompanying the photograph is incorrect but details can be gleaned from the press)

Newton’s book has revealed to me the paucity of my understanding of World War I, which has been based on my Modern History Honours studies back in ‘the good old days when children received a proper education’. For example, Newton highlights the fact that in 1914 the Australian prime minister did not have the right to communicate with his British counterpart. The Commonwealth of Australia and its federal government began on 1 January 1901. Yet such was our status in the Empire that our PM had to write to the King’s Governor-General (then it was Sir Ronald Craufurd Munro Ferguson, GCMG) to ask him to raise matters for Australia with the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Lewis Harcourt. Newton makes clear that it was our then governor-general, not our elected prime minister, who sent the cablegram to Harcourt, offering unconditionally all Royal Australian Navy ships and 20 000 soldiers to the ‘Mother Country’ – unconditionally but paid for by Australia – 40 hours before the British Government entered the war.

Newton explains that the federal ministers in discussion with Munro Ferguson saw Australia as competing with Canada and New Zealand to see which Dominion had its offer of troops accepted first by the British Government. Our response was complicated by the fact that from July 1914 Australia was in the middle of a federal election. Commonwealth Liberal Party Prime Minister Cook and some other ministers were campaigning across the country by train, as were Opposition Leader Fisher and some of his Labor parliamentary colleagues

Even more revealing, Newton details the circumstances in which the federal government had started planning, between 1912 and 1914, for ‘an expeditionary force to wage war beyond the country’s shores’. I had wondered how we were able to send troops to seize what was then German New Guinea, just six weeks after the Empire’s entry into World War I. A great-uncle of mine served with the ‘Australian Naval and Military Force’ that occupied Rabaul, then the capital of German New Guinea, on 11 September 1914. This unit was disbanded when the first Australian Imperial Force (AIF) was established. (Like so many other men, my great-uncle then enlisted in the AIF. He was killed in the Battle of Fromelles in July 1916.)

As Newton reveals, Australia was a different country before World War I. Initially, there had been opposition to the proposal by the first General Officer Commanding our military forces in 1902-04 for a mobile force of 9000 troops for ‘imperial missions’. Australia had sent 20 000 troops to the 1899-1902 Boer War, suffering almost 600 dead and leaving many Australians with a distaste for foreign wars. Following Japan’s defeat of Russia in their 1904-05 war, Australians became fearful of imagined Japanese military moves on our country. The federal government had British Field Marshal Lord Kitchener of Khartoum visit Australia to ‘advise on defending the Australian continent’. The incoming Labor government accepted his report in April 1910, including the introduction of compulsory military training. Following the 1907 Colonial Conference, Australian government policy secretly included military cooperation between Great Britain and the Dominions.

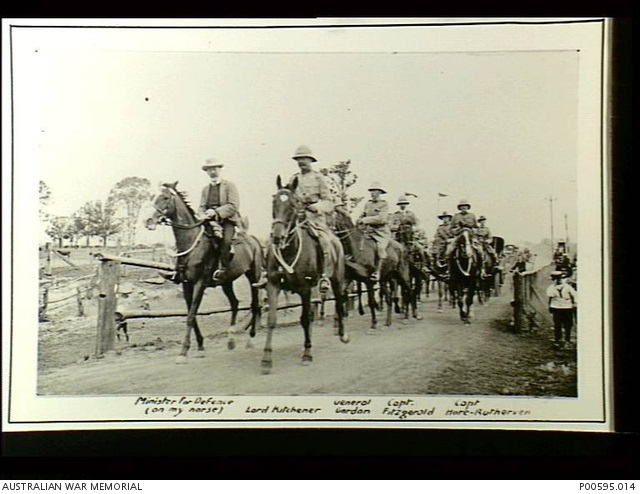

Lord Kitchener, riding near Liverpool, NSW, during his visit to Australia in January 1910, Defence Minister Joseph Cook to his left (Australian War Memorial P00595.014)

Lord Kitchener, riding near Liverpool, NSW, during his visit to Australia in January 1910, Defence Minister Joseph Cook to his left (Australian War Memorial P00595.014)

As the then Defence Minister, Cook had introduced legislation in September 1909 that required all boys aged 12 to 18 to undergo military cadet training and boys aged 18 to 20 (adult status voter age was 21 then) to undergo more intensive military training. Earlier the first Labor government began the Royal Australian Navy’s development with an order of destroyers from Great Britain. The later ‘Fusion’ Liberal Prime Minister Alfred Deakin expanded this order to add three light cruisers, two submarines and a battle cruiser. There was an understanding between the government and the British Admiralty that our ships would revert to British command in time of war.

All of these military developments meant that, in Newton’s view, Australia would inevitably follow Great Britain into war. However, as Newton spells out in great detail, the Governor-General sent our offer of troops and our navy before the British Government had decided to enter the war. From his very extensive use of primary sources, such as the papers of British Prime Minister Asquith, Newton details the struggle between those in Asquith’s government seeking neutrality and those, like First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, pushing for war. Indeed Churchill tried to force the Government’s hand by keeping the Royal Navy at war stations following a ‘test mobilisation’ instead of the usual summer manoeuvres, a provocative move indeed. As Newton points out, this move encouraged Russia and France as they jointly discussed war mobilisation. On Wednesday, 29 July, Colonial Secretary Harcourt sent a ‘[War] Warning Telegram’ to all Dominions and Colonies. Newton quotes General Henry Wilson, British director of military operations, on the dispatch of the telegram: ‘I don’t know why we are doing it, because there is nothing moving in Germany’.

The naval moves provided encouragement to those in both Australia and London pushing for war. This was ramped up when the Governor-General was able to manoeuvre the defence minister into agreeing to hand over our warships to the British Admiralty. HMAS Australia returned to Sydney to refuel and load munitions, in plain view of photographers and others around Sydney Harbour, in readiness for sailing to Hong Kong to join the Royal Navy’s China Station.

As late as Saturday, 1 August, the neutralist faction in the British Cabinet pushed for a declaration of neutrality should war break out. Newton says the neutralists were in the majority but key people sought to outmanoeuvre them. Churchill had tried to do so by keeping the navy on its war stations, a clear signal for war identified by European governments. Foreign Secretary Grey threatened to resign if neutrality was decided. Colonial Secretary Harcourt threatened to do so if the decision was for war. Finally, the Cabinet decided against sending the British Expeditionary Force to France. The Admiralty moved first by sending out orders to call up the Naval Reserve. Then Grey managed to convince Cabinet to guarantee naval support to France should the German navy attack France’s Channel ports. Grey struck again with an allegation that German troops had entered France and Luxembourg. (Britain had guaranteed Belgian sovereignty by treaty in the 19th century.) The Cabinet resignations by Neutralists started but, as Newton emphasises, they were protests against Britain preparing to embark on war for the sake of Entente solidarity (i.e. for France and Russia). Russia had triggered a German declaration of war once the Tsar authorised mobilisation.

Crowd outside Buckingham Palace after declaration of war against Germany, 4 August 1914 (National Archives of UK)

Crowd outside Buckingham Palace after declaration of war against Germany, 4 August 1914 (National Archives of UK)

Meanwhile in Australia, despite the election being underway, Prime Minister Cook and just three cabinet ministers met with the Governor-General at 3pm on Monday, 3 August, Australian time. Patrick McMahon Glynn, Minister for External Affairs, was not invited even though he was available in Melbourne. By 6pm it was all over. Munro Ferguson telegrammed London to offer 20 000 troops as well as the Navy. Canada had already offered 30 000 troops. Even New Zealand offered troops before we did. But all this was before the British Cabinet had made any decision for war. So Colonial Secretary Harcourt, a neutralist, had to inform the Government of the Dominions’ offers while still arguing in Cabinet against entering the war.

In the end the British Cabinet never did make a clear decision for war. PM Asquith did not lead in Parliament with a cry of ‘defending liberty’ or any of the other phrases later to feature on lurid wartime propaganda posters. As Newton records, there was no formal declaration of war by Britain. Instead, the British Ambassador to Berlin ‘demanded his passport from the German Government’. At 10.30pm on Monday 4 August, London time, three privy councillors met with the King, authorising two proclamations – one on shipping, the other on contraband – which referred to a state of war. So Britain and the Empire were then at war with Germany.

I found Newton’s book a wonderfully detailed exposé of the politicking that led Britain and the Dominions into such a terrible war. Never were Clausewitz’s words more true: ‘war [in 1914] was [truly] a continuation of politics with the admixture of other means’. Sadly we seem to have learned little, because Australia has found itself at war many times since 1918 ended ‘the war to end all wars’.

[1] Robert Graff, one of very few officers to survive the sinking of the light cruiser USS Atlanta, 13 November 1942, in the Battle of Guadalcanal. The ship, already hit by a Japanese ‘Long Lance’ torpedo, was mistakenly fired on twice and sunk by the Heavy Cruiser USS San Francisco. (James D Hornfischer, Neptune’s Inferno: The US Navy at Guadalcanal, Bantam Books, New York, 2011, p. 427.)

Good review of a good book – thank you. Doug Newton’s astringent scholarship is a tonic in the time of Anzackery. One minor correction: you write “… the ‘Australian Naval and Military Force’ that occupied Rabaul, then the capital of German New Guinea, on 11 September 1914. This unit was disbanded when the first Australian Imperial Force (AIF) was established.”

Two points (as the great Hank Nelson would start): It was the ‘Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force’, and it was not disbanded when the the first AIF was established – recruiting for the AIF opened on 10 August 1914, but the AN&MEF landed at Rabaul on 11 September. It was still in German New Guinea in early 1915 but was replaced by a specially formed ‘Tropical Force’.

But the minor factual points don’t derange either the value of your review or the the book in question.