‘Part III: Review of Reynolds The Other Side of the Frontier (1981)’, Honest History, 2 September 2014

Henry Reynolds’s The Other Side of the Frontier: An Interpretation of the Aboriginal Response to the Invasion and Settlement of Australia, History Department, James Cook University, Townsville, 1981, further editions later, was a landmark book in the field. McQueen’s review appeared in National Times, 11-17 October 1981.

In his foreword, CD Rowley praised those who had produced the book in a cheap format in the hope it would be widely circulated. ‘This is necessary’, Rowley went on, ‘because so far the whites have suffered no shock comparable with that affecting tribe after tribe after 1788. Before we came we had already developed the blinkers of a colonising and converting ideology. This book may (belatedly) supply part of the shock we need.’ Unfortunately, Rowley’s message sank in only slowly.

Related: Introduction; Part I; Part II

This is the most important book ever on Aboriginal-European contact. Ten years research have helped to make it so and have encouraged Henry Reynolds’s active acceptance of the subtle range of Aboriginal responses. His book is not pro-black in any sense of feeling sorry for them. Instead, Reynolds demonstrates that Aborigines were and remain the makers of their own destinies. History does not fall out of their skies: they too help to make it.

By exploring across the frontier, Reynolds has remade history as it is written. He has done the seemingly impossible by documenting the response of a pre-literate people.

The Other Side of the Frontier is so huge with ideas and so rich in detail that no review could do justice to the book or to its author, who is associate professor of history at Townsville’s James Cook University. The most that I can do here is to display a sample of what Henry Reynolds has worked so long to understand.

One of the most important parts of Reynolds’s case is that there was, and is, no such thing as the Aboriginal response. Different groups and individuals reacted according to their needs and circumstances, some with kindness and some with hostility; some with a gentleness which turned to ferocity when it was misunderstood as weakness and abused.

West Papua independence leader Jacob Rumbiak speaking at commemoration, Melbourne, 2012, for Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheenner, executed 1842 for leading Indigenous resistance to White settlement (Flickr Commons/Takver). Related article.

West Papua independence leader Jacob Rumbiak speaking at commemoration, Melbourne, 2012, for Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheenner, executed 1842 for leading Indigenous resistance to White settlement (Flickr Commons/Takver). Related article.

The guts of Reynolds’s argument depends on the flexibility of Aboriginal culture which he sees as ‘both more conservative and more innovative than standard accounts have suggested.’ By incorporating the new back into the old, Aborigines added to their inheritance, making their tradition a living process. Hence, for some young blacks, white society promised a way out of the repressiveness of a marriage system which favoured the old men.

In her opening pages of The Timeless Land, Eleanor Dark recreated the mystery and wonder brought by the sight of Captain Cook’s sailing ships in 1770. Reynolds extends the novelist’s empathy across the continent where news spread faster than explorers and straying cattle.

Friendliness was often the Aborigines’ first response because they could not imagine that their land was forfeit. As Reynolds has it, they were not aware that an invasion had taken place. He further shows that some tribal Aborigines still believe that the whites will go away. Such Aborigines agree with the Chinese historian, who, on being asked what he thought had been the impact of Christianity on Europe, replied, ‘It’s too soon to tell’.

Yet helpfulness could have had a double response with tribes providing guides so as to keep whites away from the sacred sites.

Once the fact of invasion was realised, sorcery provided Aborigines with a weapon against the materially more powerful Europeans; droughts, floods and accidents were proofs of the value of traditional culture against the occupiers. Sorcery also offered explanations for the catastrophes overwhelming black civilisation. Diseases brought by the whites were interpreted as the evil influence of enemy tribes who remained more significant to the Aboriginal scheme of things than nearby whites could ever become.

The primary question which the Aborigines had to settle was theological: ‘Were the whites human beings?’ Blacks began by recognising Europeans as their dead relatives and friends. When the whites did not remember their previous lives, Aborigines worked out that the experience of death had reduced their memory as well as their intelligence. Reynolds shows how this initial religious view of the invaders was supplemented in the Aborigines’ minds by more secular approaches.

One of Reynolds’s sources is the language coined to account for the changes brought by the whites. At first, Aborigines applied their own words for ‘ghost, spirit, eternal, departed, the dead’ to the whites. In South Australia, they ‘called white men grinkai, the term for a peeled, pink corpse’. Boots became ‘footstinkers’. One group extended its words for anything dangerous, such as snakes, to ‘alcohol, opium and medicines’.

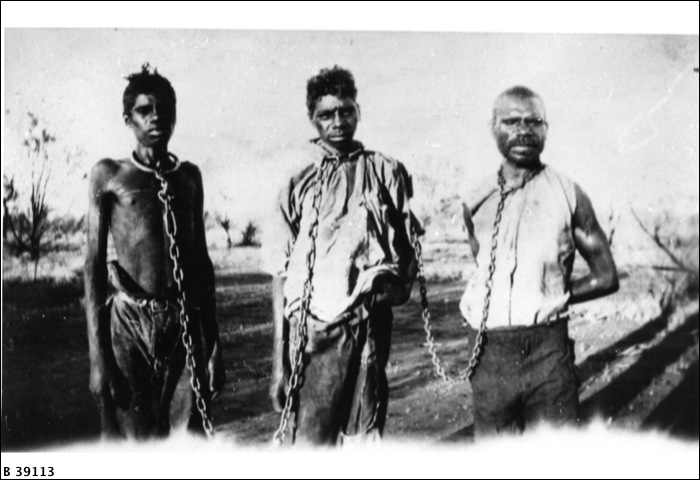

Aboriginal prisoners in chains at Coniston Station, NT, c. 1928 (National Library of Australia/State Library of SA)

Aboriginal prisoners in chains at Coniston Station, NT, c. 1928 (National Library of Australia/State Library of SA)

In a later stage, Aborigines accepted whites as beings like themselves who had to be assimilated into traditional society if they were to survive. Sexual exchange was a means to assimilation. Europeans ‘paid’ for sex with goods but these payments could never be great enough since intercourse had given the whites a kinship with Aborigines. Henceforth, what the whites possessed belonged equally to their new black relatives; or so the Aborigines believed. From the other side of the frontier, Aboriginal demands were seen as robberies. In a society where sharing is a natural order, there is no notion of thanks and so the blacks became ‘ungrateful’ as well as ‘lazy’.

Words were changed with realities and Aborigines adapted more than their vocabularies. Shortly after the introduction of dogs to Van Diemen’s Land, the Aborigines there were hunting with them. In other parts of Australia, blacks built their own stockyards for emus as well as for the sheep and cattle taken from their white relations. At one place, the Aborigines built a bridge to get sheep across a river.

Thus, blacks were willing to work but they did not appreciate why someone else had a right to take the products of their labour. Reynolds wonders why more white workers did not take the same position.

In his final chapter, ‘Other Frontiers’, Reynolds looks at contact with seamen, farmers, miners, towns and missionaries; of the last named he reports one tribesman telling a priest: ‘no more tobacco, no more halleluia’.

You do not have to agree with every point in The Other Side of the Frontier in order to be convinced of Reynolds’s basic proposition, which is transforming the whole debate about the position of blacks in white Australia.

The book’s production does less than justice to its contents. First, there is the obscurity of the publisher, who lacks the one thing which this book most deserves, namely, distribution. Secondly, there are no illustrations; the footnotes, bibliography and index are all excellent. In quite minor matters, the prose could have benefitted from an outside editor who might have abolished a slightly apologetic tone. These are counsels of perfection, readily remedied in the countless editions to come.

A third of Reynolds’s book concerns Aboriginal resistance and he conclusively destroys the comforting European story that Australia’s Aborigines, unlike American Indians and Maoris, did not fight for their lands. The legal fiction that Australia was a settled and not a conquered colony is still used to deny land rights.

The fact of Aboriginal resistance has been known even to scholars for a few years now, partly because of Reynolds’s previous publications. What his book does is to place this violence in its cultural contexts to illustrate its development and variety, showing that, at first, their ‘violence was judicial rather than martial’. Whites would not accept the rules of ‘pay-back’ and sought total domination. Widespread resistance followed. Reynolds mentions a few leaders, including a Tasmanian woman, Walyer, who should take the space now given to Truganinni. Important things are explained about Jimmy Blacksmith, that sable-skinned white bushranger.

Tunnel Creek, Jandamarra country, Kimberleys, WA (Wikimedia Commons/Whingeing Pom)

Tunnel Creek, Jandamarra country, Kimberleys, WA (Wikimedia Commons/Whingeing Pom)

Reynolds calculates that blacks killed 2000 to 2500 whites and that whites killed 20 000 blacks, nearly half of them in Queensland. This geographical imbalance does not mean that Queensland settlers were nastier. They had the advantage of coming later with more efficient guns.

In a further contrast, Reynolds notes that about 5000 Europeans from north of the Tropic of Capricorn died in the five conflicts from the Boer War to Vietnam. In another 75-year period, from 1860 to 1935, as many as 10 000 blacks were killed in fights against Europeans in north Australia.

Whites today urge blacks to forget. Blacks can’t and won’t. Reynolds reflects upon the lie of the nation of Anzacs, the country of ‘lest we forget’, telling Aborigines to do just that.

If we are unable to embrace the other side of the frontier as part of our own heritage we will stand in the eyes of the world as a people still chained intellectually and emotionally to our C19th Anglo-Saxon origins, ever the transplanted Britishers.

White Australians may find it harder to share their history than their wealth. To do so imagination and empathy will have to be extended and they are qualities which have never been greatly admired in Australian society. (Reynolds, p. 166)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.