‘Part I: Defending Australia from the Pink Peril (1973)’, Honest History, 2 September 2014

From a lecture given in Australian History III, Australian National University, July 1973. It was later printed in Woroni (ANU) 16 July 1973, then in National U (National Union of Australian University Students) 23 July 1973, then reproduced on Joe Hill and The Never Say Die Collective (blog) on 17 May 2014.

Related: Introduction; Part II; Part III

In this lecture I want to lead you away from the notion of the Aborigine as a passive recipient of history, as no more than a victim. Instead, we shall recognise the Aborigine as an active agent in European history since first contact.

There has been some improvement in historical writing about Aborigines during the last five years. Books such as CD Rowley’s The Destruction of Aboriginal Society and Peter Biskup’s Not Slaves, Not Citizens are fine examples. The Aborigine in Australian history is no longer entirely ignored. They are not actually fitted into the mainstream and so remain an interesting sidelight. But they are there. Despite this improvement, we have a long way to go.

If it is true that Aborigines are back in history courses, it is equally true they are there under sufferance, and most usually only as victims. They are seen as people to whom things happen, as people for whom we should feel sorry, as a people who need defending and for whom excuses must be found.

This condescension manifests itself in two principal ways. First, there are those who set out to demonstrate how badly Europeans treated the Aborigines. This is not a difficult task since there is a superabundance of evidence, much of it in official papers.

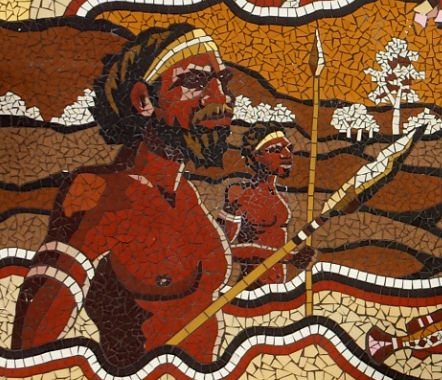

Respect Unity Peace mosaic: detail depicting Pemulwuy and Tedbury, Gough Whitlam Park, Earlwood, NSW (Gallipoli Centenary Peace Campaign/Danny Eastwood & Steven Vella)

Respect Unity Peace mosaic: detail depicting Pemulwuy and Tedbury, Gough Whitlam Park, Earlwood, NSW (Gallipoli Centenary Peace Campaign/Danny Eastwood & Steven Vella)

Secondly, there are those writers who, whenever faced with a piece of violence carried out by the blacks dig around in search of a piece of white provocation.

It is time to stop both these approaches.

In this lecture I shall turn the whole business on its head to look at the Aborigines as Australian patriots, fighting a justifiable war of resistance against the European invaders of their homelands.

Now, that is easy enough to say. But it is not very easy to ‘think’. It is not easy for a European to think himself through into this position. While I was researching this lecture I spent three days hoping I would not come across any more accounts of Aborigines killing white babies. It was not until the fourth day that I could accept the fact that killing babies was ‘a good thing’. What are the alternatives? Should the Aborigine have left them to die after killing the parents? Should they have waited for them to grow up and then kill them?

This immoral squeamishness is the least of the problems facing anyone, black or white, who wants to write the history of the Australian Aborigine as an actor and freedom fighter.

Before presenting a short history of Australia from the viewpoint of Aborigines defending their country against an invader, I need to spotlight several serious inadequacies in the account.

First, there is the question as to whether ‘history’ itself is appropriate to the retelling of the life and actions of people who did not operate on our timescale. I mention this as a serious objection to the way in which I shall present the material I have brought together.

The way in which the information is organised in terms of the time-scale is directly connected to another major problem which will have to be faced by historians dealing with Aborigines. I have arranged the material in terms of the Gregorian calendar because that is the way the people who left written records organised their materials. Because the Aborigines did not leave any records of their responses or their plans of campaign, I have to rely on snippets from their enemies.

Two more self-criticisms relate to the way in which I have written up the data I have found. I make virtually no distinction between tribes. I proceed on the racist assumption that all Aborigines are the same. All historians continue to write in this manner because we pay no attention to anthropology or pre-history. In this connection it is worth reflecting upon the following: how many Aboriginal tribes can you name? And how many Amer-Indian tribes can you give?

The last of my self-destructing objections is that I have been guilty of what Claude Levi-Strauss would describe as ‘primitive thinking’. I have uncovered a body of new data and to interpret them I have merely stood the old interpretation on its head. No native would be so unsubtle. But like most twentieth-century middle-class Europeans I am a long way from the art required to think in complex, fluid, dialectical ways. My mind has been reduced to a railway track and it takes me a very long time to see what is obvious to a savage.

I should make one further disclaimer. It would be untrue to suggest that I am the first person to have thought of writing about the Aborigine in this way. An amateur historian in Queensland in 1959 began an article on the Black war in that colony by describing one incident as ‘[t]he first place at which the Australian native struck a blow in the defence of his country’. But after spending 20 pages detailing the continuance of this defence he concluded: ‘The inborn savage instinct of the black to attack a stranger has been responsible for many deaths of settlers …’

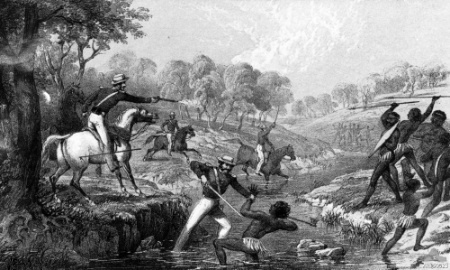

Mounted police and blacks, 1852; depicts the killing of Aboriginals at Slaughterhouse Creek by British troopers (Wikimedia Commons/Australian War Memorial)

Yet most scholars have managed not to think about the war at all. In 1947, Professor AP Elkin proclaimed that ‘unlike the Maoris of New Zealand, they did not think of fighting for their country’. Having said this, he immediately proceeds to the following:

Between 1842 and 1844, however, there seemed to be an uprising of Aborigines from Port Phillip on the south to Wide Bay in south-eastern Queensland. Incidents occurred along the frontier with such frequency that observers thought they must be planned.

What has happened is that Elkin was so full of the old notion that Aborigines did not fight for their country that he cannot perceive the importance of the evidence he produces.

One of the hoariest arguments is that the Aborigines would have obtained land rights if they fought for their land. This claim ignores the fact that, wherever they did fight, all they got was to be exterminated. It is also another example of an argument which shifts the responsibility for suffering onto the victim.

At last, it is time to begin to describe the campaign of defence.

The struggle for the liberation of Australia

In order to defend Australia, it was necessary to scare off the enemy’s advance scouts. The first European was Jansz in 1606 and at least one and possibly nine of his men were killed in the first blow struck for Australia’s independence. Seventeen years later, another Dutchman, Carstensz, was forced to withdraw when 200 local troops attacked his landing party in North Queensland.

The pirate Dampier was hounded away on both his voyages in 1688 and again in 1699. So ashamed was he by his retreat that he attempted to conceal his own fears by slanders against his conquerors. The expedition of the English invaders under Cook was subject to assault by fire when their vessel was being repaired. The use of fire was to be an important weapon in the arsenal of the Australians. It could be used against flocks of sheep, against crops, against houses, and against families without endangering the lives of the freedom fighters.

Similar tactics were employed against the agents of aggression when they proceeded overland. In this aspect of the campaign, various stratagems were employed. Frequently, the defenders would offer themselves as guides and lead the invaders into areas where their incompetence would soon seal their fate. This was how Leichhardt was defeated. More usually, straying scouts would be speared, as occurred with Oxley in 1818, Eyre in 1841, Gilbert in 1845, Kennedy in 1848 and Giles in 1873. Harassing tactics were employed to slow down the enemy’s advance, as in the case of Mitchell who was so distraught that he built a fortress to protect himself.

But before these scouts appeared there was a long period in which the invaders huddled around Port Jackson and waited for ships to bring them supplies so that they could survive. They were not robust and many of them died. Moreover, they had little idea how to hunt or gather food, they could not fish effectively and they were not very skilled at their own activities of raising crops.

The resistance in the Port Jackson area was led by the great warrior, Pemulwoy. In the 1790s his name struck fear into the hearts of the invaders and he killed several of them himself. In 1797 he led a magnificent raid on the Toongabbie outpost and attacked the punitive party sent out to capture him. He was captured but managed to escape. In 1802, he was shot. The invaders showed their barbarous natures, as well as how much they feared him, by pickling his head and sending it to Sir Joseph Banks in London. The resistance movement was carried forward by Pemulwoy’s son, Tedbury, who led attacks as late as 1809.

The White War: Tasmania

For the first 40 years, the main battles were waged in Tasmania. These commenced in 1804 immediately the Europeans appeared. Cattle were systematically speared and in 1807 a party from the white camp on the Derwent was driven back to its base and heavy casualties inflicted. This limited skirmishing continued into the early 1820s when a Port Jackson patriot, known to the invaders as Mosquito, was transported to Van Diemen’s Land. Within a few months of his arrival, Mosquito had performed two invaluable services. First, he had organised a group of demoralised Tasmanians who were living by begging and prostitution into a formidable fighting force which then conducted a series of brilliantly executed raids.

He was able to achieve this because of his second great accomplishment. From his acquaintance with the invaders at Sydney, he had learnt that as soon as their muskets had been fired, they were helpless until they reloaded. Mosquito was able to take advantage of this tactical information in the months of his campaign. He had demonstrated that weapons do not mean everything and that a disciplined and well-led force of the people can always find new means of defeating their enemies.

Mosquito was captured through the treachery of a Quisling known as Tegg. Tegg had been promised a boat if he betrayed his countryman but when he kept his part of the deal, the whites once more demonstrated their treacherous natures by refusing to keep theirs.

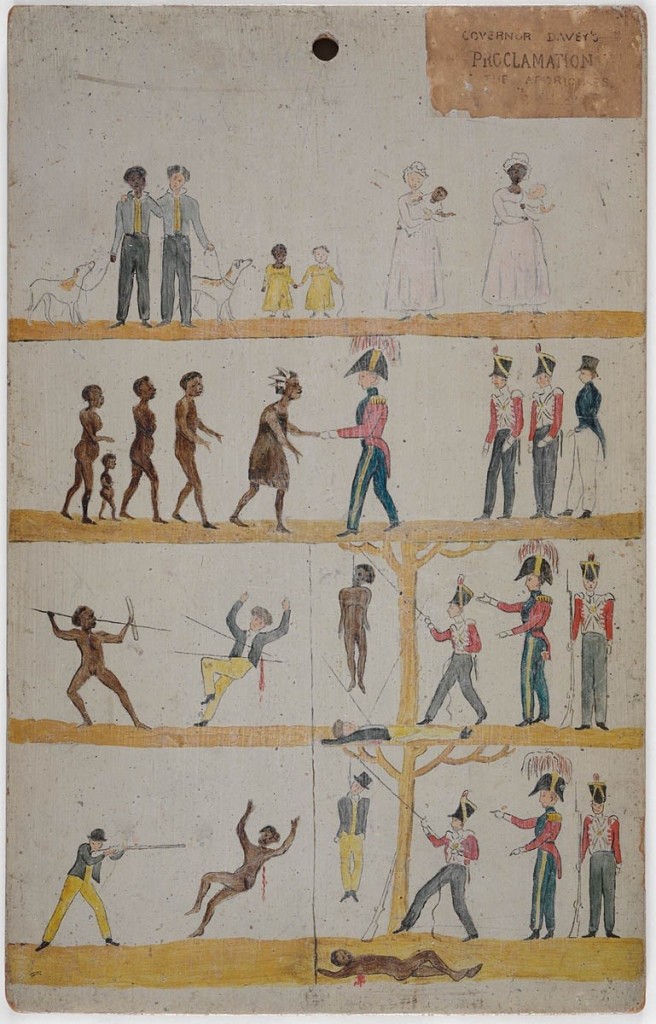

Lieutenant-Governor George Arthur’s proclamation of c.1828-1830 to the Tasmanian Aborigines; intended to publicise government policy, it was reproduced on boards and hung on trees (Wikimedia Commons/State Library of NSW)

Lieutenant-Governor George Arthur’s proclamation of c.1828-1830 to the Tasmanian Aborigines; intended to publicise government policy, it was reproduced on boards and hung on trees (Wikimedia Commons/State Library of NSW)

As the 1820s proceeded, the lessons that Mosquito had taught were improved upon and tactics devised for wearing down the invader. ‘Decoys were used, often women who led parties of white men into carefully laid ambushes. Attacks were feigned on insignificant targets to draw off men from neighbouring properties and leave their own premises exposed for plunder.’ New leaders emerged, including ‘Black Tom’ Birch who was described by a Hobart newspaper as a ‘civil or internal rebel’.

Another leader was Mon Buillietta, the chief of the Big River tribe. A report to the British Colonial Secretary described him as ‘a splendid and much feared warrior’; he displayed the characteristics of an extreme nationalist. His exploits were recorded in the songs of several tribes. Tribal chronicles recorded Mon Buillietta’s hatred of the white race and his pledge to ‘kill every white man and soldier’ and regain tribal territories.

Fire was used extensively throughout 1827 as a particularly potent weapon against the increasing number of sheep and cattle. The next year’s fighting was the most intensive and extensive so far. A different Hobart newspaper deplored that ‘the sons of the greatest Empire in the world’, having beaten the fine armies of France, were now being held to ransom by a handful of ‘black barbarians’.

In many areas, the invading farmers were forced to surrender their holdings because of continual harassment. There was a slight let-up during the winter but a Spring Offensive was launched with such good effect that the British Governor told his superiors that there was a plan ‘to destroy, without distinction of sex or age, all the whites who should fall within their power’.

So desperate had the Governor become that he proclaimed Martial Law and promised a Reign of Terror. These measures availed him little and in 1830 he asked for a further detachment of troops and for the immediate transportation of 2000 convicts. In the 1820s the local forces had lost approximately 100 troops in battle while the invaders had lost more than twice that number. It was for this reason that they decided upon their futile Black Line which cost them well in excess of £30 000 and netted two local people – an old man and a child.

Some further indication of the success of the resistance movement at this time can be gained from the comment in the Hobart Town Courier early in 1838, by which time the remaining Tasmanians had been deported to islands in Bass Strait. The paper commented that, as a result of this deportation, ‘[t]he large tracts of pasture which have been so long deserted owing to their murderous attacks on the shepherds and the stock-huts will now be available’.

Although ultimately vanquished by their ruthless opponents, the Tasmanians waged a long and heroic struggle for their homeland and thereby pointed the way to the strenuous resistance that confronted the Europeans as they moved northwards and further inland throughout the following hundred years.

1840s: general uprising

We have already noted that Elkin referred to a massive struggle in the early 1840s. In fact, this uprising was only a highlight of campaigns waged for over 20 years in the south-eastern corner of the mainland. In this protracted warfare, the patriots directed much of their attention towards the destruction of the flocks of sheep, correctly realising that in this manner they would hurt their enemies much more than if they killed only their shepherds.

A few sheep were killed for food but hundreds of thousands were killed as part of an economic war. For example, in the Clarence River district of New South Wales, William Forster and Gregory Blaxland were driven out by this tactic. Further inland around Armidale the insurgents took advantage of the mountainous terrain to conceal sheep until they could be driven over cliffs.

One of the most spectacular of these manoeuvres occurred near the border between New South Wales and South Australia. On 16 April 1841 a party of Overlanders were attacked and dispersed by several hundred Australians who drove off some 5000 sheep. When the news reached Adelaide a punitive expedition was sent out but failed to find any trace of the sheep or of their captors.

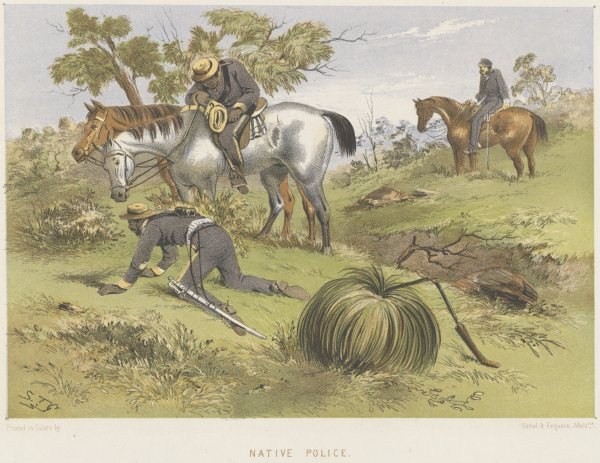

Native police 1865; ST Gill (Wikimedia Commons/National Library of Australia picture an7149195)

A second party set out early in May. This party was more successful in that they met up with their adversaries but they were less fortunate in that they were driven away by them. Towards the end of May, a third party set out with nearly 70 men. They followed a number of false leads planted on them by the local population until they stumbled upon another party of Overlanders who had been attacked, as well as upon the carcasses of 2000 sheep that had been speared systematically. The party buried the four dead whites from the second party of Overlanders and returned empty-handed to Adelaide. The bitter ashes of defeat can be seen in the report of their leader:

The cruel tribe we are now surrounded by are very numerous, and have doubtless become emboldened by having defeated three successive parties of Europeans, and having escaped punishment by any detachments.

A fourth and final punitive expedition did shoot more than fifty of the original warriors but, as the Adelaide Register pointed out on 11 September 1841: ‘It is clear, however, on the surface that no party can for the present pass safely from New South Wales territory into South Australia unless sufficiently numerous and well-armed’. To maintain the vital overland link with New South Wales, the Governor sent Edward John Eyre to establish a guard-house 85 miles from Adelaide.

Another area of constant conflict was the Eyre Peninsula. Upwards of 30 Europeans were killed there and, in the 1840s, several would-be pastoralists were driven out of the district entirely. Even the so-called Protector of Aborigines abandoned his farm and moved into town. When the military commander visited the area he described it as ‘a deserted place, more than half the houses have been abandoned, and the remainder are barricaded to protect the occupants against the attacks of the natives’.

The local defenders had taken full advantage of the isolation of the settlement to wreak punishment, as would their countrymen in the entire north of Australia for at least a further hundred years.

Queensland

When the Queensland Government held an inquiry into the success of its invasion in 1861, it was estimated that in the preceding 20 years, 250 whites had been killed in the colony. This total was far from the complete figure since, in this part of the continent heavy fighting had been going on from the first encroachments in 1824 and continued well into the twentieth century. Indeed, the first settlement at Redcliffe was shifted because of the ferocity of the attacks made by the local forces.

In the south-west corner, the tribes co-ordinated their strategies at the triennial Bunya Festivals. They also planned each particular attack, as can be seen from the assault in October 1857 at Hornet Bank Station when 11 whites were killed. Shortly before this attack, their troops had been observed in what was assumed to be a corroboree. Later, it was recognised as a training exercise. The resistance in the far west continued and was marked by spectacular events such as the capture of the township of Gilberton in 1874.

The attacks around Brisbane persisted. In the late 1840s and early 1850s they became associated with the names of Dundalli and Milbong Jemmy, both of whom were executed in 1855. Dundalli made an appeal to his countrymen from the scaffold to avenge his death by keeping up the struggle. As a punishment for this call, his hanging was bungled and he slowly strangled. As had occurred in South Australia, the government found it necessary to establish a fort at Helidon to protect its people travelling to and from the Darling Downs.

Probably the fiercest resistance was maintained in North Queensland and it was particularly successful against the incursion of gold miners in the 1880s on their way to the Palmer River fields. The terrain was ideal for guerrilla warfare. A favourite tactic was to stampede a horse team at a particularly difficult spot on the track.

In some parts of the far north, there was a virtual stand-off by the Europeans until the Second World War. The history of the Anglican Church in North Queensland reported that, as late as 1926, their missionaries had not been able to succeed with what it referred to as the ‘still war-like’ natives of the Kokoberra tribe.

The actual number of invaders killed is not known but in the 1860s it was estimated to be one in ten of all those who ventured into the outback. Certainly, there was an intense resistance for several decades, with a large number of the tactical encounters being won by the Aborigines who forced back the frontier in several places for considerable periods of time.

Although the history books have tended to leave Aborigines out after 1900, this bias does not mean that the war of resistance had ended by then. In the Northern Territory and in the north of Western Australia clashes continued into the 1930s. Many of these have become known because of the punitive expeditions which followed. These war crimes should not let us ignore the judgement of the police sergeant at Alice Springs which he voiced to the Board of Inquiry into the Coniston killings in 1928: ‘If some severe steps are not taken they will drive the pastoralists out of the country’.

About this time, Aborigines started to employ the methods of the Europeans by engaging in political protest. Deputations to premiers and letters to editors started to appear. These moves were a far cry from the attack that had been launched on the invaders across the nineteenth century but they were far from rootless attempts to imitate or compromise.

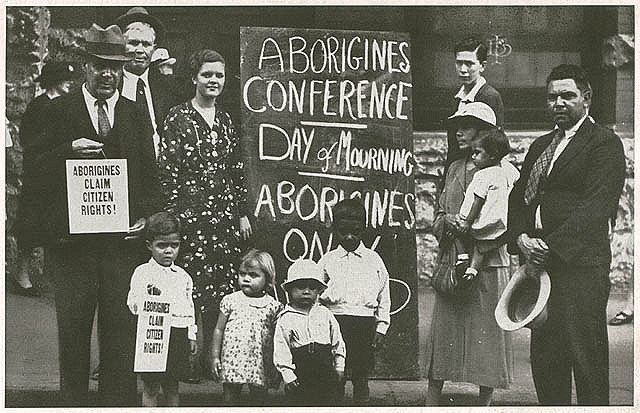

Aborigines Day of Mourning, Sydney, 26 January 1938 (Flickr Commons/State Library of NSW)

Aborigines Day of Mourning, Sydney, 26 January 1938 (Flickr Commons/State Library of NSW)

At the 1938 sesquicentenary events in Sydney, Aborigines protested against the re-enactment of Phillip’s landing and they published a monthly newspaper. The need of the Europeans to place a full-scale army in the north of Australia in the 1940s also enabled it to move freely into the regions such as Arnhem Land for the first time. Still, the resistance continued and a homestead was burnt to the ground in 1957.

Today, the resistance is spread right across the continent from the Cape Barren islanders through Redfern and on to Gove. The Black Panther Party, the establishment of the Tent Embassy in Canberra and the battles by the Gurindji have made it possible for this lecture to be prepared.

My ideas are grounded in the upsurge of Black revolt just as firmly as other historians’ ideas have been grounded in the social practice of the colonial invaders, those Lords of Human Kind.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.