Lest We Forget has come to mean ‘Remember’, or even ‘Remember, or else!’, in relation to the commemoration of men and women killed in war. The phrase was originally meant as a warning against imperial over-reach. Today, however, it comes up more often on days where what looks like patriotism is on display: these men and women died ‘for us’, we are told, or ‘to defend our values’. Their dying was a patriotic act, so remembering them must be patriotic also. Really? Following is a repost of our note of December 2018 about On Patriotism, by journalist and author, Paul Daley. Reading the repost, we were particularly struck by the review of Daley’s book by Fiona Capp in Fairfax papers: ‘Daley takes the jingoism out of patriotism to leave us with a national wellspring of which we can all be proud’. This Anzac month, as the drums of war sound, we can expect a lot of jingoism. HH

***

‘Paul Daley’s On Patriotism: an appreciation from a fellow-traveller’, Honest History, 16 December 2018 updated

This is not really a book review, though a book has set it off. The book is Paul Daley’s On Patriotism, actually an essay (15 000 words or thereabouts) in book form, part of the wide-ranging On … series, put out by Melbourne University Publishing.

Why is what follows not a review? Essentially, because Honest History has been a fellow-traveller with Daley since 2013 and we are too close to him and his work to be unbiased. Yet, On Patriotism rings so many bells for Honest History that this article just had to be written.[1]

Why is what follows not a review? Essentially, because Honest History has been a fellow-traveller with Daley since 2013 and we are too close to him and his work to be unbiased. Yet, On Patriotism rings so many bells for Honest History that this article just had to be written.[1]

Daley’s wide-ranging appreciation of what is notable in Australian history, and his particular feel for Indigenous Australian stories, reflects Honest History’s own emphases. For example, The Honest History Book (2017) was divided into sections, ‘Putting Anzac in its place’ and ‘Australian stories and silences’ (all the non-khaki strands that have often been strangled by the bloated Anzac legend). Among all the non-Anzac strands, though, the Indigenous-invader conflict has been central to The Honest History Book and to the whole Honest History enterprise. ‘That invasion of 1788 and its consequences [Alison Broinowski and I said right at the end of the book] deserve far more of our attention today than do the failed invasion of the Ottoman Empire in 1915 and our military ventures since.’

Daley has also been an advocate for many of the same causes as Honest History, while matching the highest standards of the journalist-writer’s craft. And he writes as well as or better than most of our contributors, using appropriate language to drive points home, while applying plenty of well-turned and elegant phrasing.

Even before we got the Honest History venture under way, Daley featured in one of our ‘founding documents’, articles which made points that we wanted to pursue. This was a 2013 discussion (Daley, Clare Wright and the ABC’s Jonathan Green) on imagining Australia without Anzac.

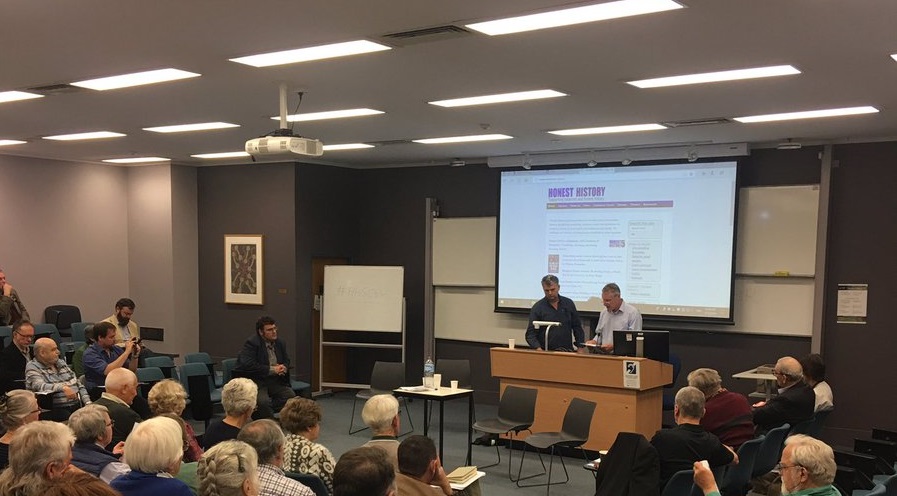

Daley then launched the Honest History website in November 2013. More than five years on, the website links to around 50 items under Daley’s name, mostly his articles in Guardian Australia. So, it was not surprising that, when we held a symposium to mark five years of Honest History, one of the highlights was the Canberra launch of On Patriotism by the ABC’s Michael Brissenden. The book contained a dedication, ‘For Honest History’.

As I said at the beginning, this is not really a review, but readers who have got this far are urged to buy, read (and re-read) Daley’s book ($14.99 paperback or less than that electronically). Unlike much of the military history literature that the book implicitly takes a stand against, it is not long-winded, turgid and laid on with a trowel, but concise, brisk and subtle. (Carlyon, FitzSimons, Kieza, Perry and the like, take note.)

Unlike these authors, too, Daley does not deal in what has been called ‘prosthetic memory’, which American historian, Jay Winter, summarised recently (at the inaugural Ken Inglis Memorial Lecture in Canberra) as a means by which people in and around the commemoration industry make emotional connections with past events and people – events and people that they do not and cannot remember – as a way of filling gaps in their own lives.[2]

The Australian War Memorial, to take one example, offers lots of prosthetic memory. It oozes from numerous speeches, is force-fed to visiting children, and one almost expects to find a piece of it for sale in the Memorial shop, perhaps attached to a magnet, Memorial-shaped and made from wood taken from a descendant of the Gallipoli Lone Pine ($9.99). Even the traditional phrases, Lest We Forget and We Will Remember Them, are redolent of prosthetic memory: can we forget or remember something we have never known?

The Memorial recently offered a virtual reality version of the Battle of Hamel, putting audiences ‘at the heart of this key action alongside the Australian and American soldiers who fought there’. You could choose to be an infantryman, a pilot, or tank crew. Taking part in this show would have done wonders for prosthetic memory: ‘it was just like being there at the time’, one can imagine people saying.

There is more of the same at the Monash Centre at Villers-Bretonneux in France. ‘The experience’, according to the Centre’s website, ‘is designed so visitors gain a better understanding of the journey of ordinary Australians – told in their own voices through letters, diaries and life-size images – and connect with the places they fought and died. A visit to the Sir John Monash Centre will be a moving experience that leaves a lasting impression.’ Almost like you were there in France a hundred years ago; a prosthetic memory to take home to Australia.

Michael Brissenden launches Paul Daley’s book, Honest History symposium, Canberra, 8 November (Twitter/@taniazora)

Michael Brissenden launches Paul Daley’s book, Honest History symposium, Canberra, 8 November (Twitter/@taniazora)

What Daley offers, on the other hand, is a way of grounding ourselves in something truly Australian, finding ourselves in a place where we belong, not in the artificial spaces of Anzackery spawned in another hemisphere. He wants us to connect to ‘a continent so storied, one with a spirituality and civilisation history as deep as it is ancient’. He wants non-Indigenous Australians to ‘accept the invitation [from Indigenous Australians] to stop, think about and proudly accept that this is all part of a narrative bringing their lives and those of their ancestors into perspective too’ (pp. 103-04).

Billy Griffiths, in his book Deep Time Dreaming, quoted Arrernte-Irish-Kalkadoon man, the late Charles Perkins, a distinguished activist and public servant, saying something very similar. A good Australia, Perkins said, will be ‘when White people would be proud to speak an Aboriginal language, when they realise that Aboriginal culture and all that goes with it … is all part of their heritage … [A]ll they have to do is reach out and ask for it.’ Daley’s book helps us reach out.

The book is full of paragraphs that made this reader say things like, ‘Right on!’, ‘Yes, exactly!’ and ‘Hear! Hear!’ but here are just a few:

In the Australian quest to determine who and what we are, did our political and cultural leaders ever draw on this [Indigenous] inner wellspring of complexity and beauty for a character or – better still – a story of formative nationalism to project outward to the world? No. Instead, they’ve confected a national foundation myth around two experiences drawn from overseas: 1788 and Anzac (pp. 52-53).

Country is a kind of memory – it is memory laid down by the lives of one’s family, by the events of one’s childhood, by the journeys of one’s ancestors, and by the tensions and conflicts of a changing world. Historical, mythological, familial and personal narratives are all layered, sedimented, in places where they happened (pp. 55-56, quoting John Carty of the South Australian Museum).

With the end of the festival of Anzac 100, which rolled to a close on Remembrance Day 2018, is it too much to hope that Australian commemoration hereafter takes a more solemn turn, away from the eulogising politicians and the sound-and-light shows? Is it too much to hope that other extraordinary elements of our continent and its history – the enduring civilisation and remarkable survival against the odds of Indigenous people; Australia’s global precociousness on women’s suffrage and workers’ rights; the tension between our multiculturalism and treatment of refugees; a wilderness that’s the envy of the world and the pioneering activism to protect it; and our country’s early role as a global multilateralist – will no longer be shrouded in the darkness of the Anzac eclipse (pp. 94-95)?

This [the Australian story based on a feeling for Country] is Australia’s truest story. It comes from the heart of our continent, not some other shore. If Australia would project this remarkable aspect of its being with half the energy it dedicates to Anzac and European arrival, how very different, how nuanced and rich, the complexion of our patriotism would be (p. 104).

In Australian major party politics today, while there are occasional outbreaks of dissent on questions of national identity, publicly rethinking either the big exclusive national celebration of non-Indigenous Australia on 26 January, Invasion Day, or the veracity of attaching national birth to 25 April, is pretty much heresy (p. 108).

We have already “broken away” and become an independent nation except in two crucial respects: we are without an Australian head of state and we have yet to anchor our vision of popular sovereignty in the continent’s Indigenous antiquity as the Uluru Statement from the Heart invites us to do. This is the true source of a more mature and independent Australia – the grounding of our sovereignty on our own soil, in the songlines and histories of an ancient island continent (p. 117, quoting historian Mark McKenna).

Paul Daley (MUP)

Paul Daley (MUP)

The book begins and ends with personal stories. The opening one, about Anzac Day in Daley’s Catholic primary school, will touch your funny bone. The closing one, about the Central Australian Aboriginal Women’s Choir, The Song Keepers, at the Sydney Opera House, singing (to much applause) German hymns in Pitjantjara and Arrernte, will leave you with some hope for a future where Australian patriotism grows from our own soil and not from the nostalgic scrag ends of military or colonialist adventures kept alive by the peddlers of prosthetic memory.

* David Stephens is editor of the Honest History website and co-editor of The Honest History Book, which includes a chapter by Daley, ‘Our most important war: The legacy of frontier conflict’.

ENDNOTES

[1] Reviews elsewhere include: Fiona Capp in Fairfax (‘Daley takes the jingoism out of patriotism to leave us with a national wellspring of which we can all be proud.’); Ingeborg van Teeseling in Australia Explained (‘Daley’s essay is a call to arms, an attempt to shake us out of our lazy stupor.’); Lisa Hill in ANZLitlovers (‘Alas, On Patriotism is pitched, it seems to me, at the converted.’); Christopher Hartney, University of Sydney, in Academia (a long review, difficult to summarise, but tending to the critical); Peter Donoughue on Not about Books (‘Persuasive in its central argument that Australian patriotism must be rooted in our ancient, indigenous past.’) Google book extracts. Daley on ABC Sydney.

[2] ‘Emotion’ (in commemoration frequently a synonym for ‘teariness’) should not be confused with ‘empathy’ (understanding). For more on prosthetic memory see: Alison Landsberg, Prosthetic Memory: The Transformation of American Remembrance in the Age of Mass Culture, Columbia University Press, New York, 2004. Landsberg argues that ‘the technologies of mass culture make it possible for anyone, regardless of race, ethnicity, or gender to share collective memories – to assimilate as personal experience historical events through which they themselves did not live’. See also Winter’s definition of ‘collective remembrance’.