‘Labour and the Great War from a dozen perspectives’, Honest History, 4 August 2014

Ernst Willheim* reviews Frank Bongiorno, Raelene Frances and Bruce Scates, ed., Labour and the Great War: The Australian Working Class and the Making of Anzac, Australian Society for the Study of Labour History, Special edition, Labour History, 106, May 2014

_________________________________________________________________

Why did so many ordinary working men flock to enlist for the Great War? What role did the leaders of the Left play to encourage or to resist the outbreak of nationalism, patriotism and militarism? Is the Anzac legend a celebration of sacrifice or a conservative evocation of nationalism and militarism? Why, a century later, do so many young Australians make the pilgrimage to Anzac Cove? These timely essays raise (but do not necessarily answer or explain) these and many related questions about the Anzac legend and the Australian working class.

The contributions by Douglas Newton (‘At the birth of Anzac’) and Mark Cryle (‘Natural enemies?’) present starkly different pictures of the roles played on the one hand by Labor’s political leaders, enthusiastic supporters of the war effort, and, on the other, opposition by the industrial wing and radical and leftist journals. Why the difference?

In contrast with the desperate efforts of socialist and social democratic organisations in Europe, through the Second International and domestically, the Labor Party in Australia was an enthusiastic early supporter of the war. Labor leader Andrew Fisher’s unqualified commitment to defend Britain ‘to the last man and the last shilling’ – a commitment made at a time when the British Cabinet was still divided – is well-known. That commitment was made in the heat of an election campaign. Labor was undoubtedly sensitive to a charge of disloyalty.

Robin Archer (‘Stopping war and stopping conscription’) contends that, unlike in Europe, there was no flurry of efforts in Australia to prevent the outbreak of war. The Australian Labor Party had little interest in and involvement with the Second International. Was it merely a question of expense or is the explanation deeper? Why did the Australian Labor Party lack the strong anti-militarist spirit of the German, French and British leftist parties? In sharp contrast to the mass anti-war demonstrations in Europe and to the clear denunciations of the move towards war coming from European Labour leaders, Australian Labor leaders made no attempt to denounce the pending war or to rally opposition to the war.

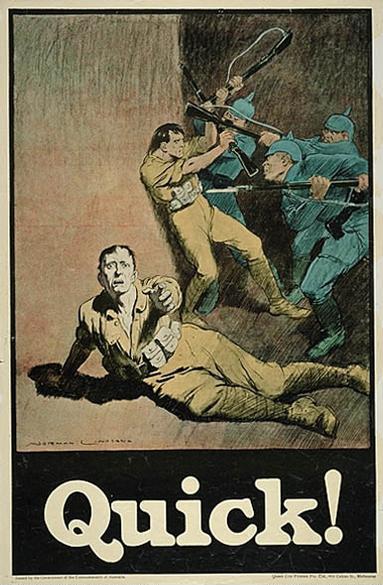

Propaganda cartoon by Norman Lindsay, c. 1918 (Wikimedia Commons)

Propaganda cartoon by Norman Lindsay, c. 1918 (Wikimedia Commons)The essays point up the sharp difference; this reviewer would have wished though to see deeper investigation of the reasons for it. Was one reason that the Australian party lacked the theoretical base, the intellectual and ideological rigour of the leftist parties in Europe? Was such strong support for war really in the interest of the working class?

Archer offers the interesting suggestion that the political strength of the party in Australia meant it had more at stake, making it more difficult to resist popular enthusiasm for war. Some may see a parallel with the apparent inability of the Labor Party today to take a principled stand on refugees.

An alternative view would be that political strength could have provided the base for principled leadership. Was the Labor Party’s subsequent opposition to conscription something of a paradox? Or was it, as Archer suggests, possible precisely because of that political strength? Alternatively, was the failure to counter popular enthusiasm for war a failure of leadership? Just as Australian Labor’s failure to organise any anti-war effort stands in stark contrast to the anti-war efforts of European leftist parties, so Australian Labor’s opposition to conscription contrasts with the failure of European leftists to oppose conscription.

As might be expected in a collection of essays, unanimity of judgment is absent. Cryle identifies articles and editorials in trade union and other radical and leftist journals taking unequivocally anti-war positions. The radical press sustained vigorous criticism of war profiteering, militarism and the need for class solidarity. The industrial wing of the labour movement expressed discontent with the parliamentary wing. Bearing in mind the apparent contrast between enthusiasm for the war effort on the part of the political leadership and the anti-war writings by the industrial wing, analysis of these apparently contradictory positions would have been welcome. How widespread was the anti-war movement? Was there serious dissension between the political and industrial wings of the labour movement? How was such dissension played out?

Clearly the essays have been written in isolation from each other. Individual contributors have not sought to consider or comment on the different views and emphases of their co-contributors. The absence of any co-ordination left this reviewer somewhat unsatisfied. Comparison of contrasting views is made difficult by the absence of any index, an obvious weakness in an otherwise valuable publication.

An interesting essay by Nathan Wise, based on unedited diaries of those who served, examines tensions in working relations at the front line, including different motivations and different attitudes to military service. Some men with specialised skills took pride in their work but hated the ill-informed demands of arrogant officers. Others saw manliness in evading the demands of officers and took pride in dodging work.

Anti-conscription cartoon by Claude Marquet, Australian Worker, 13 December 1917 (Newspaper Collection, Courtesy State Library of Victoria; Migration Heritage NSW – Powerhouse Museum)

Anti-conscription cartoon by Claude Marquet, Australian Worker, 13 December 1917 (Newspaper Collection, Courtesy State Library of Victoria; Migration Heritage NSW – Powerhouse Museum)There is considerable breadth in the topics covered. Melanie Oppenheimer’s essay contrasting the humanitarian ideals of the Red Cross with its enthusiastic promotion of militarism also links the creation of the Anzac legend with Australian women Red Cross volunteers and the sale by the Red Cross of a militaristic pamphlet, ‘Australia at the Dardanelles’. Val Noone contends that Daniel Mannix’s strong opposition to the first conscription referendum was influenced in large part by his living in working class West Melbourne. Although mention is made of support for conscription by Protestant clergy, there is no comparable analysis of the influence, if any, of Protestant working class on Protestant clergy or of the influence of Protestant clergy on their working class adherents.

Essays by Nick Dyrenfurth, Phillip Deery and Frank Bongiorno, and Bruce Scates and Melanie Oppenheimer take aspects of the story through the subsequent decades. Nevertheless, despite the subtitle, ‘The Australian Working Class and the Making of Anzac’, there is little consideration of the impact of the war on working people in Australia and on working class families whose menfolk were at war, of the effect of bereavement on working class families or of the political involvement of returned soldiers, most of whom were, as several writers note, from working class backgrounds.

One irritating stylistic feature for the non-specialist reader is the frequent detailed, almost encyclopaedic reference to and summaries of earlier writings, to the extent that an author’s own themes are almost lost. Nevertheless, at a time of excessive concentration on the battlefields of Gallipoli, these essays on the working class and Anzac are very much to be welcomed. As always, there is more to be done.

_________________________________________________________________

* Ernst Willheim is a Visiting Fellow in the College of Law at the Australian National University. He was previously a senior government lawyer. His professional expertise is in public law (constitutional law, international law, human rights, indigenous issues).

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.