Peter Stanley

‘Honest History: possible, desirable, necessary? Eldershaw Memorial Lecture to Tasmanian Historical Research Association, Hobart, 12 August 2014’, Honest History, 4 November 2014

Good evening ladies and gentlemen, colleagues, friends, and especially members of Peter Eldershaw’s family. I thank the Tasmanian Historical Research Association for the invitation to deliver this lecture, an opportunity to contribute to the discussion of history, and particularly Australian history and what it can mean here and across the nation and beyond. I’m conscious of the distinguished historians who have preceded me in this place and hope that tonight’s lecture is worthy of them. I’d also like to acknowledge the original custodians of the land on which we gather.

I stand here in at least two capacities: as a scholar of Australian and specifically Australian military-social history, something to which I have devoted my career, so far, and as the President of the group Honest History. It’s with the idea of honest history that I mean to deal in this lecture, though my background and experience as an historian means that I will return to military history as the substance and exemplar of the idea, the more so because we are now marking the centenary of the Great War, and it colours our thoughts about the honesty of our history.

I’m grateful to the Tasmanian Historical Research Association for giving me the opportunity to speak tonight, because it allows me to reflect on and consider the phenomenon that is Honest History. But I’m sorry that I don’t have more to say specifically about Tasmania, its past and its archivists and historians, among whom we remember Peter Eldershaw. I suppose that, in that the idea of Honest History is, or ought to be of universal concern, then the idea is as relevant to Tasmania as anywhere. But I would like to acknowledge that Tasmanian archivists and historians have been notable protagonists of the idea of Honest History, even before the term was coined. I’m conscious of, for example, the way Tasmanian archivists and historians – and particularly family historians – challenged the notion of the ‘hated stain’ of convictism and over the past fifty years recovered and used surviving convict records to reveal a part of the island’s history that previous generations would have preferred to have left unexplored and unspoken.

In that connection, of course, the work of Peter Eldershaw as Principal Archivist at the State Archives and as a founding member of the Tasmanian Historical Research Association embodies the idea of Honest History. Peter’s determination to find, identify records (and if necessary rescue and requisition them), to preserve, list, and make them available, and to write with regard to evidence rather than reputation offers an admirable and still relevant example to those who follow. Today, Hamish Maxwell-Stuart’s work, to me, continues to manifest the values that Peter Eldershaw expressed. In writing about Tasmania’s convict past he insists on relying on evidence rather than on either romantic or gothic myth in looking at the reality of convict settlements.

Tasmanian historians have also been among the most fearless in acknowledging the fact of frontier war. They include Lyndall Ryan and Henry Reynolds, historians whose honesty has got them into hot water with petty critics unwilling to face the truth of colonial violence and conquest. I’m conscious that Marilyn Lake’s book A Divided Society, on Tasmania in the Great War, was not only the first ‘state’ study of that war’s effects on society, but that she exposed the divisions, strains and tensions of that time – and at a time (1975 – sixty years after the war) when some of the protagonists were still about.

Among Tasmania’s military historians I would single out Craig Deayton, whose history of the 47th Battalion, Battle Scarred, dealt more openly with the dark side of the Great War than is usual in a battalion history, or UTas MA candidate Andrea Gerrard, whose thesis on Indigenous men in the AIF powerfully unites Indigenous and military history to produce novel and challenging conclusions. So Tasmania does not need to be schooled in producing history that can be regarded as being Honest History before we coined the term. But the term perhaps requires explanation and certainly discussion, because its existence challenges us all.

Honest History launch, Canberra, 7 November 2013: Peter Stanley introduces Paul Daley (Honest History)

Honest History launch, Canberra, 7 November 2013: Peter Stanley introduces Paul Daley (Honest History)

In a recent issue of the professional journal History Australia I offered a ‘short history of Honest History’ – necessarily short because the group only coalesced in 2012 and formed and launched its website by the end of 2013. In the nine months since much has happened, both in the little world of Honest History and in the larger world of Australian history. This evening I want to both reprise that discussion of the origins and growth of Honest History and offer some observations from its vantage point. (As one of my fellow Honest History office-bearers says, I speak from Honest History, not for it.)

I should make clear my position from the outset. I make a good living from writing military history. I may present myself as a military-social historian and have taken positions and offered interpretations that might be seen as critical of the traditional understanding of the Anzac legend, but there’s no escaping the fact that I’m commenting on Anzac and what it means from the inside, as it were. I worked at the Australian War Memorial for 27 years and for the last twenty of those years was the Memorial’s senior staff historian, associated with the creation of half a dozen of its permanent galleries, some of which are for the moment still in being. So I might be seen as a Pharisee of the Anzac religion, a high priest or even theologian.

I think, though, that if I am a theologian I might be seen as a practitioner of liberation theology, or one of those New England agnostic bishops who think it probable that Jesus was either actually his sister or at least nominated Judas as his Vicar on earth but there was a mix-up with the papyrus. Now that I’m not only no longer a public servant, I’m more free to speak my mind. This I now proceed to do.

What is the phenomenon of Honest History and how did it come about? In what we might now have to call the First History War, during John Howard’s term as prime minister, you might recall that articulate conservative ideologues were encouraged to confront and oppose versions and visions of Australia’s history that they found unsatisfying and, indeed, illegitimate. You might recall this period – one of the most unpleasant clashes occurred over Keith Windschuttle’s misguided criticisms of the work of Lyndall Ryan and Henry Reynolds and the casualty statistics of the frontier war in Van Diemen’s Land became one of their battle-sites. Those criticisms, which so often missed the wood for the trees, were bruising for individuals and damaging to the collective practice of history. They might have made us check our footnotes more closely – always a caution to me, because my motto is that ‘every error you find is surely the last you made’ – but ultimately unproductive because they stunted imaginative, empathetic, bold and truthful history-making. There is a word for historians who make no errors: it’s ‘unpublished’.

Other individuals and institutions offering different versions of Australian history felt their ire. Many would rather forget this dark period, and certainly do not relish re-living it; though we seem to. It may well be seen that the group known as ‘Honest History’ has coalesced at a time that may be seen as the ‘Phony War’ of what, depressingly, may become the ‘Second History War’. With the election of Tony Abbott’s government and particularly following the appointment of a combative conservative Christopher Pyne as federal Minister for Education, it seems likely that a second round of debate, discussion and argument will consume Australians who care about how their past is represented and interpreted. This time around, those who seek a principled, historically justifiable and balanced approach to interpreting the past may find resources and support thanks to the formation of the discussion and lobby group Honest History, whose supporters will no doubt soon find themselves drawn in to whatever skirmishes and clashes will come.

Honest History is a voluntary group that coalesced in Canberra early in 2013 and quickly attracted supporters and participants all over the country. Its initial organising committee included as secretary former public servant Dr David Stephens, Michael Piggott (former Melbourne University archivist), Richard Thwaites (former ABC correspondent) Dr Sue Wareham (of the Medical Association for the Prevention of War) and Professor Marilyn Lake, formerly of this parish, now of Melbourne University. I accepted the invitation to become president, on what turned out to be the spurious grounds that the role would be largely ceremonial. The group invited ‘supporters’ willing to be seen in its company and soon attracted many distinguished historians and others, including Michelle Arrow, Joan Beaumont, Frank Bongiorno, Judith Brett, Pamela Burton, Anna Clark, Ann Curthoys, Joy Damousi, Tom Griffiths, Stuart Macintyre, Mark McKenna, Tony Taylor, Christina Twomey, Ben Wellings, Richard White, Damien Williams and Clare Wright. Collectively they represent a spectrum of gender, age, experience, expertise, interest, approach and ideology, but all have endorsed the idea of speaking for a vision of Australian history, as Honest History’s mast-head puts it ‘neither rosy glow nor black armband … just honest’.

At first promoted by more-or-less monthly e-mail newsletters, from late 2013 Honest History has been represented by a website (honesthistory.net.au), which was launched by author and Guardian Australia journalist Paul Daley at Manning Clark House in Canberra in November. The website, created by several volunteers (engaged retired folk of the kind who make such a contribution to community organisations, in Canberra as elsewhere) reflects the group’s commitment to diversity and open debate. It now includes over 800 items – articles, papers, and links to historical resources – with an emphasis on making challenging and diverse views available. It features ‘Jauncey’s View’, a rotating blog, named after the outspoken Australian economist Leslie Jauncey and his wife Beatrice, neatly allowing Jauncey bloggers to cross gender lines without complication.

The Honest History site continues to grow organically, with blogs, book reviews, articles, multimedia and relevant links contributed by supporters. Its entries are indexed under various headings, extending far beyond the categories ‘Anzac’ or ‘war history’ (where the push originated), encompassing social, economic, diplomatic, cultural and environmental history, and ‘the use and abuse of history’. Honest History will, we hope, particularly support secondary history teachers seeking a wider range of perspectives in grappling with the new and challenging national curriculum. (If academic historians and museum curators are the fighter aces or shock troops of the History Wars, secondary history teachers are its spear-carriers; often as bemused about what the fight is about as any hoplite or conscripted legionary.[1]) These resources include papers or items by or about commentators and historians of all kinds, conservative as well as those espousing the liberality and diversity Honest History represents – you can find the Townsville champion of the Anzac legend Mervyn Bendle there as well as Marilyn Lake. Diversity is the strength of Honest History. It is already attracting both visitors and criticism, not least from Mervyn Bendle – a sign of success, I think.

Honest History does not see itself as just a website. It hopes in future to engage in and host discussions, both in person and online, and offers a rallying point or a source of support, a resource that may come to be especially useful to those considering Australian history over the course of the coming centenary of the Great War. Its supporters, those informed or encouraged by its diverse and iconoclastic attitude to the interpretation of the past, will be important not just for the practice and presentation of Australian history but for Australia’s public discussion of its past. Honest History’s supporters hope to make their collective voice heard in discussions already canvassed in its newsletters and website and in public forums. It is a loose coalition – a broad church – and its supporters, and even members of its organising committee do not necessarily agree on everything.

***

How did Honest History come to emerge in Canberra at this time? The influences operating upon it are worth reflecting on.

Several strands coalesced to provide the impetus to form what has become Honest History. First, it drew on the campaign run in Canberra from late 2010 against the proposal for the erection on the shore of Lake Burley Griffin of huge concrete monoliths commemorating the two world wars. This campaign resulted in the formation of a coalition of peace and heritage activists, historians and citizens, the Lake War Memorials Forum, who saw the proposal (by a private company, the Memorial(s) Development Committee) to build the memorials wither under the assault of critiques drawing on an intimate grasp of the relevant heritage legislation and a deep residual respect for what the Australian War Memorial (which the proposed memorials would duplicate) represented. This campaign brought the coalition’s key members into contact.

The Lake War Memorials Forum’s campaign succeeded partly because of its members’ willingness to make common cause with seemingly unlikely allies – the Burley Griffin Society, the Medical Association for the Prevention of War and individual military historians. By late 2012, when it seemed likely that the campaign against the memorials was likely to prevail, some members of the coalition’s informal organising committee began discussing ways to mount a critique of the Anzac legend through a television documentary funded by a competitive grants program. The application failed, but the research and discussion underpinning the submission seemed worth finding a continuing presence for the critical views animating its proponents.

Underlying the development of the idea of Honest History was, of course, the evolution of the centenary of the Great War (aka the ‘Centenary of Anzac’) and the Department of Veterans’ Affairs ‘Century of Service’ program. It grew out of a bipartisan (but heavily ideologically freighted) commission headed by former prime ministers Malcolm Fraser and Bob Hawke (and a couple of make-weights to represent ‘community’ sentiment). The Fraser-Hawke commission recommended a range of ways by which the centenary of the Great War might be marked. Closely managed by senior officials in the Department of Veterans’ Affairs, it was mulched through a number of consultative committees providing advice (not always heeded) which produced the program announced by Julia Gillard’s government in 2012. The program was basically accepted and implemented by the Abbott government, albeit with an augmented budget, despite its general budgetary retrenchment.

This is important, because there’s a common assumption that conservative governments foster adulation of Anzac (as Hobart saw when John Howard accorded Alec Campbell, the last Anzac and a life-long socialist, a state funeral). But the adulation began, if anywhere, with Bob Hawke’s 1990 pilgrimage to Gallipoli – the last one with live Anzacs – and with Paul Keating kissing the ground at Kokoda in 1992. Anzac worship became entrenched with John Howard’s pilgrimages to the Western Front, Hellfire Pass and Isurava, and his adoption of Les Carlyon and later Peter FitzSimons as court writers-about-military history – but the important point is that an uncritical, nationalist celebration of Anzac has been a bipartisan approach for over twenty years.

Honest History launch, Adelaide, 9 October 2014: Melanie Oppenheimer and Michael Piggott (Honest History)

Honest History launch, Adelaide, 9 October 2014: Melanie Oppenheimer and Michael Piggott (Honest History)

And remember, behind all of these influences we need to reflect that Australia has been at war – though not exactly a nation at war – since the attack on the World Trade Centre in September 2001, and certainly since the commitment of Australian troops to wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, conflicts about which Australians remain ambivalent. While the salutary example of the Vietnam War has rightly deterred all from projecting their opposition to the war onto those serving, unease over the fact of Australia’s participation in these conflicts has led many to question the congruity between the Anzac legend and the promotion of wars that many people see as unjustifiable and unwinnable.

All of these strands figured in prompting a small group of historians and citizens to propose a body taking an interest in, and indeed expressing concern about the ways in which Australian history is being practised or presented. The group debated the need for and the rubric under which they might offer a coherent contribution to public debate. Though at first unduly focused on a critical view, especially of the excesses of what Geoffrey Serle called ‘Anzackery’ – the uncritical adulation of Anzac (a useful term Honest History has helped to resurrect and propagate) – gradually a more positive idea emerged.[2]

Through debate (most of it carried on by e-mail) the idea of a lobby group ‘Honest History’ coalesced, and with it the slogan ‘not only, but also’. This has come to be expressed as not only Anzac, but also other aspects of Australian history; in war history, not only soldiers but also civilians; the home front as well as the battlefront; victims as well as slouch-hatted heroes; the negative effects of war as well as the familiar rhetoric of what war ‘gave’ ‘us’. Honest History’s essential contentions are that that diversity in history is desirable, and that the simplistic idea that there can or must be one view of Australian history (whatever that may be) should be resisted. Its proponents are reluctant to accept that school students need to be ‘taught’ about Australian history (instead of forming their own justifiable understandings based on the evidence). Honest History eschews dogma and is comfortable with heterodoxy. It has no 39 Articles, still less a catechism or a test of orthodoxy. It supports no single ‘line’ and remains open to where the debate about Australian history will go – as long as debate occurs.

Who is welcome to join Honest History? Actually, Honest History does not have ‘members’, but invites anyone to contribute to its website and the debate that Honest History sees as essential to a healthy public culture. Honest History’s reception seems a promising sign that historians, and indeed anyone with an interest in the ways history can be practised and represented, think that there is a need for such a group.

Honest History stands for the idea that history should not be something officially endorsed or imparted, still less one interpretation endorsed or enshrined by powerful agents in our society, whether they be the federal government or one of its agencies, or a corporation with a reach based on newspaper, television or multi-media ownership. Even if the History Wars do not resume – and we can be hopeful rather than optimistic – we may have need of the ideas that Honest History articulates and the vision which it expresses: not only, but also.

One of the perils of becoming involved in a ginger group such as Honest History is that if you’re not careful you end up presenting a face to the world that can be seen as negative, carping, picky and generally grumpy; however well- intentioned and pure in motive. Every blog, tweet, review, conference presentation or keynote address is, unless you’re prudent, an opportunity to bang a drum. This, as you would expect, does not go down well in the long run.

Honest History as a group has anticipated and acted to head off this fate. If you look at its website you’ll see a great range of contributions – reviews, blogs, op-ed pieces, discussions and analyses – written by a range of writers, not all of whom would necessarily agree with each other.

But at times such as this – and I mean during the present centenary – drums may need to be banged. Even though one of Honest History’s pleas is that we try to broaden our conception of what Australian history is and how we conduct and relate to it, I am of course an historian of war above all, and I feel a need to reflect on how Australians see their military history. I want to offer those reflections with an eye cocked at the centenary of the Great War that is breaking over us even now, with the inflection that here it is presented as the centenary of Anzac.

First, I want to name the day. There’s been a growing trend to capitalise the word – capital A-N-Z-A-C. This is, I think, significant. There’s no historically justifiable reason to capitalise ‘Anzac’ when it’s used to mean ‘the idea of Australians and New Zealanders’ experience and memory of war’. ‘Anzac’ began as an acronym used by clerks’ in an office in Cairo early in 1915, and it was and remains an acronym when referring to the military formations in the world wars that rejoiced in the title of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps. But Anzac became a word soon after 25 April 1915 – Cove, spirit, legend, Day; Anzac the place and Anzacs the people – and as a word it doesn’t need capitals. I don’t have the time to document this, but the evidence, while somewhat ambiguous, is incontrovertible en masse. From the title of Charles Bean’s 1922 official history of Australia and Gallipoli, The Story of Anzac, to the legislation controlling the use of the word (passed in 1916) Anzac quickly became and largely remained a capital-A-small-n-z-a-c word.

That has changed in the past decade, and now it’s as often rendered in capitals as in a mixture. Why, and what’s the point? Why? Essentially because (I think) people and organisations believe that putting the word in capitals acknowledges its importance. This was certainly the reason given by the management of the Australian War Memorial in the last decade of my time there, a policy that it’s recently reversed: I hope a sign of keeping it in proportion. It was historically fallacious, but it was essentially an emotional reason, a sign of the way that Anzac is seen in Australia as what Ken Inglis called a ‘secular religion’. (Today a lot of usages employ a hybrid. By rendering the word Anzac and day in capitals graphic designers, who are creative but not the most historically sophisticated people, have a bob each way.)

I suggest that capitalising Anzac represents a seemingly increasingly common attitude of reverence for the day and what it signifies. Anzac Day is changing and always has: the capitalisation of the word signifies, I suggest, an undue reverence, much as the ancient Hebrews capitalized the name of JAWEH and how archaic Bibles talked about the Lord your GOD. I call this capitalized word the ‘shouty ANZAC’, and I’ll leave its implications for discussion.

This may all sound pedantic: who cares whether we use capitals or not in writing ‘Anzac’? Isn’t it more important (as I’ve argued about whether we use Kokoda Track or Kokoda Trail) that we know what it means? Yes, of course: but it’s a pretty important word and concept for Australia, and the different uses indicate important differences in attitude. And, as we consider the looming centenary, we can see that there is a need for the idea of Honest History.

Australia is taking the centenary of Anzac – known to the rest of the world as the centenary of the Great War – more seriously than most nations. The federal government began planning it earlier than anyone, in about 2008 as I recall from my time as a public servant, and Australia appears to be investing more in it per head than any other nation, a total of about $175m in government money and perhaps as much again in corporate sponsorship, assuming that companies come good on their pledges. And this at a time of drastic budgetary retrenchment by the federal government.

The present centenary program, big on commemorative gestures (such as the risible planned ‘re-enactment’ of the departure from Albany of the first convoy in 1914) is long on ephemeral events but short on substantive and especially critical history. The sense that the centenary, and especially the officially endorsed or funded program, was likely to entrench a parochial, nationalist and sentimental view of the Great War began to attract concern among those who favoured a less parochial view of the experience and memory of war. Even more, some worried that the ‘Century of Service’ proposed by DVA (essentially because DVA’s veteran clients were all but Great War veterans and felt left out of a commemoration that did not recognise their service) would focus public attention unduly on a four-year festival of ‘memorialisation’, to use the bastard Americanism that has come into vogue.

Albany coffee shop prepares for influx of visitors. ‘Meanwhile, Albany’s Rustlers Steakhouse said 1.5 tonnes of meat was packed into the cool room in anticipation of the equivalent of “three New Year’s Eves in a row”.’ (Perth Now/Justin Benson-Cooper)

Albany coffee shop prepares for influx of visitors. ‘Meanwhile, Albany’s Rustlers Steakhouse said 1.5 tonnes of meat was packed into the cool room in anticipation of the equivalent of “three New Year’s Eves in a row”.’ (Perth Now/Justin Benson-Cooper)

The first big ‘event’ we’ll see will be the Albany re-enactment, calculated – in every sense – as both a television spectacle and as a mechanism to boost tourist visitors to the Albany region. It demonstrates what is wrong with the way the centenary is being ‘managed’, to the detriment of justifiable history. It began as an opportunistic ploy by members of Albany’s local government to gain funding and tourist income by boosting and exploiting the coincidence that in late October 1914 most of the Australian and New Zealand transports carrying the earliest contingents to the war assembled in King George’s Sound. Even though the transports barely saw the town and very few men were allowed off the ships to visit the town, Albany is claiming an intimate association with them, and more. It is even claiming to be the birthplace of the ‘dawn service’, even though it is very clear that the idea of a dawn service was first expressed in Brisbane in 1916, and the Albany dawn service got under way only in the 1920s.

The words I’d use here are mendacious and meretricious: two vigorous early modern words, ideally suited to invective. Mendacious: essentially untruthful; meretricious: ‘alluring by show of flashy or vulgar attractions … pertaining to or characteristic of a prostitute’.

I should note that Albany has ‘form’ here as a site in which history is manipulated. You might recall that in 1985 Prime Minister Bob Hawke did a deal with the Turkish government. In exchange for the Turkish government formally naming the little bay at which the Anzacs landed in 1915 ‘Anzac Koyu’, the Australian government agreed to allow a memorial to Mustafa Kemal Ataturk on Anzac Parade in Canberra and the naming of a stretch of Lake Burley Griffin as ‘Ataturk Reach’ and the entrance of Princess Royal Harbour, Albany, as Ataturk Entrance.

In 2014 Albany’s community leaders are touting the anniversary of the convoy’s brief stop in the adjacent roadstead as, they say, ‘one of the most significant places in the world with regard to the Anzac legend’. What, as significant as Gallipoli or Pozieres or Villers-Bretonneux? The word ‘Anzac’ had not even been coined in 1914: so how is Albany remotely connected to the Anzac legend? I had my say on this courtesy of the ABC’s radio program Bush Telegraph, and to read more of the contenders’ views please go to its website.

So I hope that you can see why Honest History is concerned that the Anzac centenary needs to be kept honest by interventions such as this. Not that Honest History’s views will count: ABC television has signed up to give us live telecast of whatever transpires in King George’s Sound on 1 November. Whether this has anything to do with a justifiable interpretation of what happened there a century before literally remains to be seen.

But the mendacity won’t stop at Albany, of course. We will see ceremonies and events elsewhere – surfboats off Anzac Cove, for example, or re-enactments of the ‘snowball’ recruiting marches of 1915-16 – and all sorts of historical guff, all masquerading as history. Some of it will be true and justifiable – and I acknowledge that almost all of it will be proposed in a spirit of wanting to remember, for the noblest of motives. But somehow, much of it surely will get it wrong. A great deal of Anzac history is either outright dishonest or plays fast and loose with what we might call the whole truth. As the journalist Tom Hyland recently observed, the centenary is already generating events and products that imperil the dignity and solemnity – and the historical integrity – of the anniversary.[3] We will face sports carnivals, a surf boat carnival off Anzac Cove (a bay that has neither tide nor surf), Anzac cycle races that have no historical connection to Anzac besides the name – the epitome of Anzac commercialisation, of a kind that was supposedly outlawed by the legislation to protect the use of the word ‘Anzac’). We will see concerts, commemorative medals, television mini-series and many, many documentaries (most of which I seem to be in). (This is a dilemma: should you stand aside in disdain, or get involved in the hope of influencing producers, directors and writers?) We will see new museum galleries (including massive new galleries at the Australian War Memorial, produced at the cost of beggaring every other major federal museum), the sprucing up and re-dedication of memorials, and new interpretative centres, not just at Albany, but also the wholly unnecessary one funded by the Abbott government at Villers-Bretonneux in France. Villers-Bretonneux already has the Australian national memorial and the local museum, renovated with Australian money, which will probably be killed off, like a corner shop when a supermarket opens down the road.

Great War fever has begun in earnest in Britain. The Guardian journalist Simon Jenkins last week wrote powerfully about how the centenary has overwhelmed the popular media there. I usually disdain wholesale quotation, because I think it’s lazy, but I’m going to break my rule this evening because Jenkins offers a terrible portent:

Britain’s commemoration of the Great War has lost all sense of proportion. It has become a media theme park, an indigestible cross between Downton Abbey and a horror movie. I cannot walk down the street or turn on the television without being bombarded by Great War diaries, poems, scrapbooks and songs. The BBC has gone war mad. We have Great War plays, Great War proms, Great War bake-ins, Great War gardens … There is the Great War and the Commonwealth, the Great War and feminism, Great War fashion shows and souvenirs. There are reportedly 8,000 books on the war in print. The Royal Mail has issued “classic, prestige and presentation” packs on the war that “enable you to enjoy both the stories and the stamps”. Enjoy?[4]

And so on. This surprised me, because Australia hasn’t yet reached this depth of obsession. (And I say ‘surprised’ because Australia has been planning its Great War centenary longer and will spend more on its centenary per head than anyone). Indeed, I think that for us the ‘real’ centenary will hit in April 2015, so I say ‘yet’.

But we are still seeing despicable and deplorable manifestations of the exploitation of the centenary. Let me mention two.

Australian Associated Press has just launched what it calls ‘Australian War Stories’. This is a clever exploitation of the availability of individual service records available digitally, and the ability of digital production and marketing techniques. Some of you may recall the ersatz ‘family history’ books that were in vogue about thirty years ago that were essentially generic templates into which family names were dropped to simulate a family life and times. You’ll recognise the style: you provided the manufacturer with a few names and dates and hey presto cutting and pasting did the rest:

Australia’s pioneering families worked hard to build the colony of TASMANIA. The SMITH family arrived in HOBART in 1849 as FREE SETTLERS. They found a bustling settlement still in the grip of the convict system, some of whom also came from IRELAND.

But if you were descended from the Browns from Somerset arriving in South Australia in 1837 you got much the same text.

Australian War Stories invites us to ‘Discover the personal war story of your loved one, written for you and presented in a beautiful hardcover book’. Drawing on even more sophisticated digital techniques is even more cynical. Its pitch is that you buy multiple copies – so that the whole ‘family’ has a hardback volume ‘an heirloom your family will treasure now and for generations to come’.

Creating this instant heirloom involves some digital manipulation, in every sense. It uses a stock of standard ‘bits’ to connect ‘you’ and ‘your relative’ with a 10 000 word generic history of the war. For example: fill out the box ‘on what date did your relative enlist’ and you get the page summarising the war on that day. Tick the box ‘Gallipoli’ and you get a selection of out-of-copyright or licensed images to connect them with a generic summary of the campaign (including images of the famous Anzac ‘charge’ faked by the British photographer Ernest Brooks). AAP has the nerve to tell us that this packaged bogus history will show that ‘every person’s story is different’, even though about 90 per cent of every book will be identical. It is ersatz history, but it’s all yours for just $1795 for 15 copies (plus $25 postage).

Perhaps the most disgraceful of these exploitative events will be ‘Camp Gallipoli’, to be held across Australia and New Zealand next April, which will rent you a spot to drop your swag for up to $150, or sell you an ‘authentic’ swag in ‘1915 styling’ for $275. ‘Sleep under the same stars as the original Anzac heroes did 100 years ago’, its website entices, eat ‘great tucker’, watch Peter Weir’s Gallipoli (you can boo the supposed British officer – actually the Australian brigade major – ordering the light horsemen to their deaths), and wake in time for a dawn service: presumably seeing the very same sun that shone on the original Anzac heroes, at no extra cost. This tawdry, exploitative nonsense would be unworthy of mention, except that it’s endorsed by the Anzac Centenary Board, the federal minister for education, Christopher Pyne, the departments of Veterans’ Affairs and Defence, the RSL and Legacy.

Camp Gallipoli promotion (Camp Gallipoli website)

Camp Gallipoli promotion (Camp Gallipoli website)

I warned you of a certain grumpiness. When I read of mendacious offerings like Australian War Stories and Camp Gallipoli I think that the whole tone of the Great War centenary is wrong. What, after all, was the Great War? Was it a triumph of Australian national identity and achievement on the world stage: or was it a global catastrophe, a war in which ten million combatants died, and as many civilians? And for Australia at least 60 000 soldiers; perhaps another 10 000 post-war, and 12 000 civilians: not that we remember the civilians at all)? What is there to be celebrated in the way the war was fought? Was the supposed achievement of the Anzac legend and the greater sense of national identity worth both the cost in lives and the elimination of the progressive, democratic Australia that died in the bitterness of the conscription campaigns and the ALP split, in a nation traumatised by death, political and sectarian bitterness and division; no longer optimistic but now conservative, fearful of the forces unleashed by the war (such as Bolshevism); and, for all the pride in Anzac achievements, strangely timid in ways uncharacteristic of that confident, pre-war Commonwealth.

This is the problem. For all that Australians are motivated by a sincere desire to remember the cost of war, a genuine wish to commemorate those who died and (less often) to recall those who suffered through the war, we again and again fall for commemoration that pays lip service to the war’s destructive effects and instead emphasises the heroic and the national.

For example, while Australia as a nation is enthusiastically embracing farewells to idealistic volunteers of 1914, surf boat races to commemorate the landing on the peninsula or ‘snowball’ marches to remember the last of the volunteers who enlisted by their own free will (as opposed to the many fewer volunteers of the second half of the war, who were pressured and coerced into enlisting by a variety of economic or emotional levers) perhaps we might think of other episodes from the war that we could re-enact.

For example:

- We could enjoy re-enacting the persecution of German Australians. There were 70-odd towns with German names across the country that were made to change to ‘English’ names and then were allowed to change them back. We could make towns like Hahndorf change back to Ambleside and abuse as ‘disloyal’ anyone who objected.

- If they really can’t take the joke we could intern them. This needn’t be malicious – and it could make great reality TV. We could readily find a TV production company willing to turn the experience into a sort of Big Brother with barbed wire.

- Then there’s White Feather day, when young women approach eligible young men, present them with a white feather and berate them for not having enlisted

- We could re-enact pro- and anti-conscription meetings and rallies, though we’d need to get the St John Ambulance as a sponsor, and at Beaconsfield the two could make an explosive mix.

- Then there’s re-enactments of the food riots of 1917, or the Red Flag riots of 1919, when supporters would get into civil disturbance, which could be educational and good fun.

- Finally, what about a ‘return of the wounded day’ when people could gather to watch vintage cars carrying visibly disabled young men to hospitals. Union Jack flags will be provided but somehow no one will feel much like waving them.

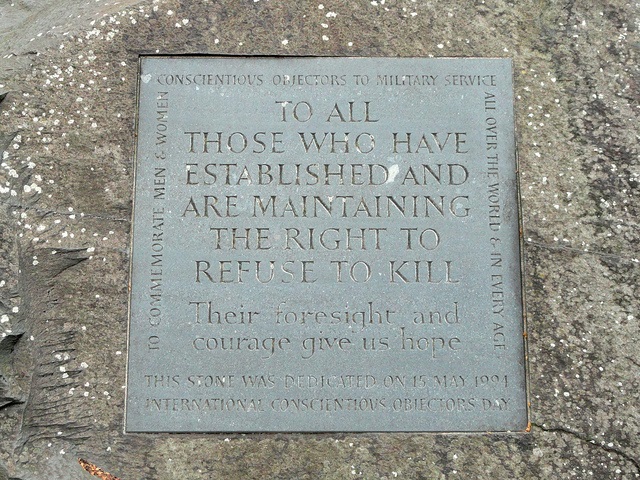

Conscientious objectors memorial, Tavistock Square, London (Flickr Commons/Peter Hughes: unchanged)

Conscientious objectors memorial, Tavistock Square, London (Flickr Commons/Peter Hughes: unchanged)

Of course this is in bad taste. That’s the point. War is in bad taste. It’s not pretty. It’s not enjoyable. It’s not fun. It wasn’t then and it shouldn’t be now.

I offer these ideas to remind you that the Great War brought division and tension to Australians at home as well as death and wounds to those who fought, and the idea of re-creating their experience is of course as grotesque as would be re-enacting other aspects of their war. I speak from experience. Just over a year ago I spent the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg among re-enactors on (or rather near) the battlefield and can report that the idea of even attempting to re-create combat, from that or any other war, is both ludicrous and futile. This is a pity, because I also discovered that I like dressing up: but while we might look the part of the past we can never actually satisfactorily reenact it. At Gettysburg I saw no fear, confusion or despair; still less horrific wounds and violent death: it was like a costume picnic with loud noises; a carnival of pretence: it was, ultimately, dishonest.

But I don’t want to merely stand in judgment on others’ treatment of Australia’s military history. If Honest History means anything it offers us a way to keep ourselves honest. In that spirit, and finally, I want to reflect on the importance of what Honest History represents for military historians like me in particular.

I came to see that one of the reasons I became involved in Honest History is because I realise that like virtually every other Australian military historian who wants to be published, I had fallen for the Faustian bargain that rules our lives. Let me explain.

As you doubtless know, Mephistopheles, the devil’s representative, presents Faust with a bargain: Faust gives the devil his soul in return for worldly knowledge and pleasure. And of course it ends badly for Faust.

We have also struck a bargain, because war history in this country is not the same as, say, economic history or transport history or medical history; or the history of colonial Australia or of the depression or whatever. As Billy Hughes’s famous (if garbled) claim suggests, war and military history in this country has been accorded a special standing. We justify it in all sorts of ways – we point to the importance of war in supposedly creating the nation, in re-shaping Australia’s relations with Britain, the United States and Asia; we argue that the place of Anzac in the national and individual psyche or the extremity of suffering and the quantum of loss gives war a particular power in the story we tell.

This may all be true. But we also know that by making these claims we are gaining a marketing advantage with which historians of trains or health or convicts can’t possibly compete. For about thirty years – and certainly since publishers began to explicitly see military history as sellable by appealing to national sentiment – military historians have found themselves caught up in this game.

Honest History launch, Melbourne, 13 October 2014: David Stephens and Peter Stanley (Honest History)

Honest History launch, Melbourne, 13 October 2014: David Stephens and Peter Stanley (Honest History)

We have benefitted from large, well-funded and organised collections of official and private records documenting war experience. Experiences less susceptible to masses of official documentation naturally suffer by comparison. Research has followed the archive, even though the archive may not reflect the Australian people’s historical experience proportionally. (For example, think how easy it is to find individual men who served in the AIF compared to those who did not: it’s an absolutely fundamental skew, so the experience of a minority of Australians in the Great War – those who volunteered and served – has somehow become the one everyone thinks of and writes and reads about: the minority has prevailed over the majority.)

My point is that as a group Australian military historians – and I include myself in this critique – have become unthinkingly complicit in a trend which (I think) exaggerates implicitly or explicitly the importance of war in Australia’s history. War occupies a special place in our historiography. But should it?

The test of this becomes clear when we consider one of the fundamental drivers of research and publication in our field, the claim that something deserves to be published or read because it has been ‘forgotten’. It’s an easy mark to identify books in Australian military history that claim to be re-discovering or exposing or celebrating something or someone that has been ‘forgotten’. (Again, I’m complicit in this. I’ve never published a book with ‘forgotten’ in the title, but my last book was Lost Boys of Anzac, about the dead of the very first wave to land on Gallipoli who died on 25 April 1915 – ‘lost’ because their bodies actually were lost – and the effects of their deaths on their families. But note how subtly I’m advertising it: even as I lament how Anzac worship has turned us into prostitutes I’m parading my wares before you! The word you’re looking for is ‘meretricious’.)

But it’s such a common practice that this business of finding ‘forgotten’ subjects deserves to be exposed as bogus. How can we possibly claim that something actually has been ‘forgotten’? What level of ‘remembering’ constitutes something not being forgotten? A book every three years? A memorial in the past five years? A documentary film? A feature film? Sometimes the idea of ‘forgotten’ is risible: the Korean War, for example, which is called the ‘forgotten war’ every time it is mentioned so if you google ‘Korea Forgotten War’ you get 2.3 million results. Korea must now be the most remembered forgotten war in history. Sometimes ‘the F word’ is justified, as in Henry Reynolds’s powerful Forgotten War, which shows that frontier conflict truly has been erased from memory and awareness over the past century. But it would do the rest of us good to resolve not to talk about remembering or forgetting for the duration of the centenary.

Compared with other nations our exposure to war has been light, and yet we act as if it’s the most important aspect of our history and we exaggerate its traces, finding ‘forgotten’ things that were never lost and inventing other aspects (like the complete beat up of the so-called ‘Battle for Australia’ in 1942). The only time when war seriously affected a significant segment of Australia’s people – in the frontier war fought across the continent for a century – it is widely denied and ignored, despite the traces of war that remain in the disruption to indigenous society. As a society, regardless of politics, we devote massive resources to preserving, displaying, publishing and making available our military heritage, which has the effect of distorting the significance of war in our history.

Ladies and gentlemen, as I hope you can see, I am not seeking to lecture you from on high, loftily enjoining you to embrace an Honest History as a faith that has saved me. Even as I urge the tenets of Honest History upon you I am conscious that the very relationship of my field, military history in our Australia, confronts me with choices, one of which is to entice me to write history not because it is worthwhile, but because it sells. Over the next four years we will all face many opportunities to fall for the blandishments of politicians, marketeers and historical demagogues of all persuasions, including authors and even historians. I wish you well in keeping your history honest.

Thank you

Note: Since 1967 the Tasmanian Historical Records Research Association has hosted the Eldershaw Memorial Lecture at which a distinguished Australian historian speaks. Peter Eldershaw (1927-1967) was a founding member of the Association and was editor of its Papers and Proceedings until his death. He was made an honorary life member in 1958. An outstanding archivist, he played a leading role in framing the Tasmanian Archives Act 1965. This Act was a milestone in Australian archival legislation.

[1] See Stuart Macintyre and Anna Clark, The History Wars, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2003 and, for a revised view a decade on, Anna Clark, ‘The History Wars’, in Anna Clark and Paul Ashton, Australian History Now, NewSouth, Sydney, 2013, pp. 151-66

[2] James Curran and Stuart Ward reveal that Geoff Serle coined the word in his ‘Austerica Unlimited’ in Meanjin, Vol. 26, Nop. 3, September 1967, pp. 237-50; The Unknown Nation: Australia after Empire, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2010, p. 121

[3] Tom Hyland, ‘No honour in commercialisation of “Disney” Diggers’, The New Daily, 30 July 2014.

[4] Simon Jenkins, ‘1914: the Great War has become a nightly pornography of violence’, Guardian, 4 August 2014.

Peter, fine speech …. perhaps not as oratorical as Noel Pearson’s at Gough Whitlam’s in Sydney, but very fine and illuminates the whole purpose and idea behind HH extremely well.

Peter

Thanks very much for this critically self reflective piece on the task of the historian and the silences in current Australian history