‘Great War chaplains after the tumult and shouting’, Honest History, 4 August 2015

John A. Moses* reviews Linda Parker’s Shellshocked Prophets: Former Anglican Army Chaplains in Inter-War Britain

_______________________________________

At a time when all denominations are being pilloried for the misdemeanours and crimes of their respective clergy and lay workers, especially against children, it is refreshing to read a study of clerical decency, altruism and entrepreneurial endeavour on behalf of human welfare generally. As ‘vessels of clay’, that is, mere men subject to all the usual human frailties, clergy can exhibit the qualities that the laity were educated to expect of them. Jesus had, after all, admonished His disciples when He was washing their feet to emulate Him as ‘one who serves’ (Luke 22: 27 and John 13: 12-16).

Of the 3030 Anglican chaplains who served in the army during the Great War, scarcely any could have returned to ordinary parish duties unchanged in their views on the Church’s role in the nation. Many had reflected on the big theological issues, such as how could a benevolent God allow such slaughter and destruction among nations that were all assumed to be worshippers of the same God?

Army chaplain tending British graves, c. 1915-18 (Wikimedia Commons/Daily Mail postcard)

Army chaplain tending British graves, c. 1915-18 (Wikimedia Commons/Daily Mail postcard)

Indeed, post Versailles, what was now to be the role of the Church in a rapidly changing society and especially in relation to the State? Here, of course, the established Church was centrally challenged. The Church of England had for centuries been used to attacks, direct and implied, from Rome and other churches for being largely a ‘theological debating society’; after the Great War it became a repository of revolutionary ideas for social renewal. The fact that the Anglican Church does not function as an ecclesiastical dictatorship, but allows reasonable debate and encourages local initiatives in each diocese, enabled some clergy who had been stirred up by their front-line experiences to come out as real social activists, not to mention theological stirrers.

Traditionally, the Church of England was a notoriously conservative form of organised Christianity. The Reformation had left Ecclesia Anglicana with an identity crisis and it had begun to become confused, both theologically and institutionally. After the turmoil between 1549 and 1662, when the Henrician legacy had been resolved, there finally came the Elizabethan Settlement which located the Church in a legally unique position between Popery and Calvinistic Protestantism. Internally, although the Church was ‘established’ by law, it continued to be a theological debating society.

Despite this the Church had developed a considerable missionary enterprise and led the campaign against slavery. As well, by the later 19th century, it became the cockpit for competing theologies which served – and still to this day serve – both on the one hand to cripple the Church’s witness, for example, as is still the case in the Diocese of Sydney,[1] but at the same time to stimulate adventurous ecumenical outreach and renewal, as occurred between the 17th and 19th centuries with the extension of dioceses overseas and the revival of religious orders, both for men and women, not to mention prison chaplaincy and the foundation of grammar schools. In short, the Church was considerably more than the ‘Tory party at prayer’.

Of course, the big question addressed so diligently in this book by Linda Parker was how did Ecclesia Anglicana, in its self-perception as being the Church of the world’s greatest empire, cope with the enormous social and political changes produced by the Great War. It is here that the former chaplains came to the fore. Their front-line experience had challenged them to query the relevance of the Church in its traditional form to the needs of a radically changing society.

Padre with wounded man being brought in on a light railway, c. 1918 (Flickr Commons/National Library of Scotland)

Padre with wounded man being brought in on a light railway, c. 1918 (Flickr Commons/National Library of Scotland)

Above all, now the working class had found its political muscle in the Labour Party. This came as a welcome development to the already existing concern of many clergy to intensify ministry to the industrial proletariat (for example, through the Church Social Union 1889-1919 and the Church Socialist League 1906-24).[2] Britain, like all countries post 1918, underwent serious internal upheavals. Extensive strikes, culminating in the general strike of 1926 and the threat of revolutionary action during the Great Depression, signalled to the dullest of clergy that the Gospel message of liberation was meant for the here and now and not just for the hereafter; hence the emphasis on the ‘social gospel’. Energised by their war-time experience, returned chaplains embraced the need for change.

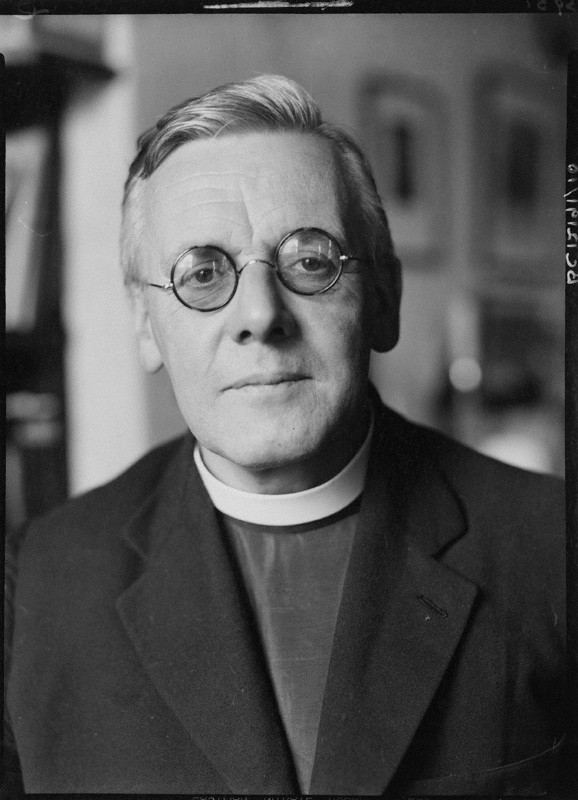

Cosmo Gordon Lang, Archbishop of York 1908-28, and of Canterbury 1928-42 (James Woodward)

Cosmo Gordon Lang, Archbishop of York 1908-28, and of Canterbury 1928-42 (James Woodward)

Linda Parker has been remarkably diligent in investigating the Church of England’s response to all these challenges. Her coverage of the sources, both secondary and primary, has been exemplary and she has made a welcome addition to studies of British social history in the interwar period, thereby correcting some of the skewed interpretations of earlier writers such as Robert Graves and Alan Hodge (The Long Week End, 1940). Her literature review is most comprehensive and refreshingly critical. So, Parker’s work is both a corrective and a revelation. It brings home with considerable force the peculiarity of Anglicanism, say in contrast to the Church of Rome, the Orthodox and the so-called nonconformist British-based churches.

Chaplain GA Studdert Kennedy MC, known as ‘Woodbine Willie’ because he handed out cigarettes to wounded soldiers (Hymntime)

Chaplain GA Studdert Kennedy MC, known as ‘Woodbine Willie’ because he handed out cigarettes to wounded soldiers (Hymntime)

Above all, this peculiarity was expressed in the kind of men who presented themselves for ordination. Some were vigorously evangelical, others were equally vigorously Anglo-Catholic. Both kinds of men served as chaplains during the war. Each group was deeply affected by the experience. The front line not only brought competing denominations together but also served to break down intra-Anglican divisions to some extent. One can still, however, identify, on the one hand, citadels of extreme evangelicalism such as Wycliffe College, Oxford and Oak Hill College, London, which line up with the militantly evangelical institution of Moore College in Sydney. All of them are examples of theological flat earth societies.

On the other hand, there are Anglo-Catholic colleges such as Keble College and St Stephen’s House in Oxford and the College of the Resurrection in Mirfield, Yorkshire. These radically different types of institutions mirror the classic divisions within Anglicanism, indeed a situation with which the Church has had to live. It was and is not all negative, however. Out of these historic divisions after the Great War emerged priests who had been chastened, sensitised and broadened sufficiently to cause them to become proactive in confronting a very much changed world.

It needs to be stressed, of course, that the great hopes for national renewal after the Great War, especially on the part of the former chaplains, were illusory because of the diffuse nature of the reception of the Christian Gospel among the servicemen. Linda Parker is right to emphasise the point. It is fair to observe that Christianity had seeped into British culture differently – as one must expect when one compares the nature of Christianity in other countries. Obviously, in places like France and Poland, Christianity equated mainly with Romanism; in Germany the impact of the Lutheran Reformation resulted in a more or less creative and abrasive religious dualism.

In England, on the other hand, the Reformation heritage was diffuse, despite the fact that Anglicanism retained its position as the established church. This heritage ensured that free thinking became synonymous with being English. It is impossible to envisage an England that was and is not diffuse in its religious tendencies.

Perceptive clergy after the Great War were well aware of this and, as Linda Parker points out, their efforts at revival had to take account of this diffuseness. But this circumstance prevented any possibility of a national conversion about which some clergy may have cultivated starry-eyed hopes. The reality frustrated any such dramatic result. Zealots among the returned chaplains did, however, set out to make the church more relevant in a number of spheres. These included industrial relations, the welfare agency called Toc H, clergy training, liturgical reform, public morality where contraception was a hotly debated issue, and pacifism. In each of these areas the driving force was former army chaplains. Their objective through their activism was to penetrate the rapidly changing British society with the humanising message of the Christian gospel.

Tubby Clayton 1937 (National Portrait Gallery, UK/Howard Coster)

This, of course, was ‘mission impossible’ but success was registered in some areas such as Toc H, founded by a priest named PB (Tubby) Clayton and which had set up on the Western Front a rest and recreation place for soldiers of all denominations to recover from the rigours of combat. This occurred in December 1915 at the Belgium town of Poperinghe. After the war Toc H (which means Talbot House in army abbreviation) moved to London where it still exists and has branches all over the British Commonwealth. Padre Tubby Clayton (1885-1972), born in Queensland, was the archetypical Anglican priest, interested first and foremost in welfare of men, refraining from pushing religion too hard but maintaining a chapel for reflection in all the houses, wherever they were.

A key additional field was industrial relations, covered in Parker’s chapter, ‘Chaplains, industry and society’. Here many priests worked indefatigably for improved industrial relations throughout the interwar period. Parker’s study presents a range and depth of information about how the Church sought to bring its mission to a diffuse society, to make its liturgy more relevant (Prayer Book reform) and to become, in short, the medium of social reconciliation and improvement. Of course, there can be no judgement on whether the Church succeeded. What can be said is that, largely inspired by the former chaplains, it really tried to witness to the Gospel in a rapidly changing world.

Finally, the word is that Christianity has limited relevance in present day Britain. One should remember, though, that it is a historic movement that, by all accounts, cannot be exterminated, though it may be severely reduced in its social impact. This is most evident from the history of the Soviet bloc, where the various regimes of ‘real existing socialism’ did all they could to marginalise the Church. The question is whether the materialism of English society will prove an even greater threat to Christian existence than the government-directed anti-church policies of the Soviet dictatorships were in their day. Linda Parker’s book suggests strongly that, whatever the challenges of atheistic materialism are, the Church of England will produce priests ready willing and able to resist them.

* Reverend Dr John A. Moses is a historian of Germany and Europe and an ordained Anglican priest.

[1] See the recently published monograph by Professor Brian Fletcher, An English church in Australian Soil: Anglicanism, Australian Society and the English Connection since 1788 (Canberra: Barton Books, 2015) pp. iv + 284.

[2] Cf. John A. Moses, Trade Union Theory from Marx to Walesa (New York, Oxford, Munich: Berg 1990), pp. 166-170.

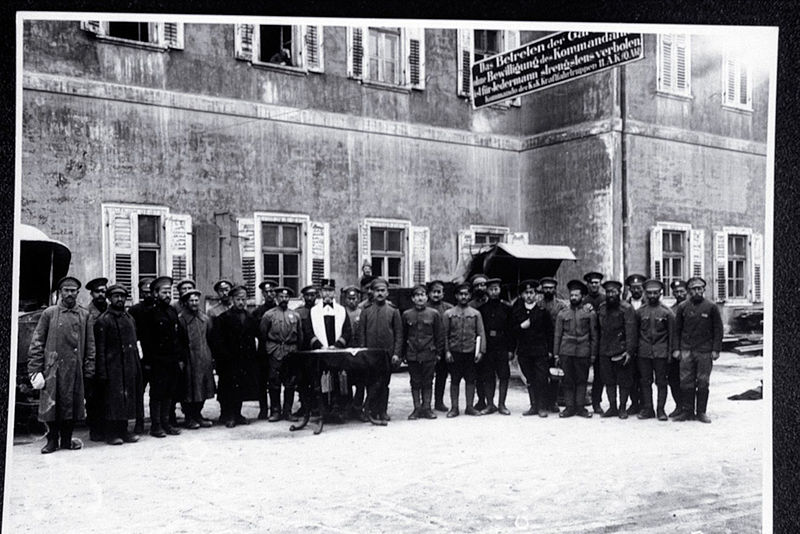

Jewish chaplain of the Austro-Hungarian army conducts Yom Kippur service for Jewish Russian prisoners, c. 1915-18 (Wikimedia Commons/Leo Baeck Institute)

Jewish chaplain of the Austro-Hungarian army conducts Yom Kippur service for Jewish Russian prisoners, c. 1915-18 (Wikimedia Commons/Leo Baeck Institute)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.