‘Robert Macklin’s Castaway is an interesting and informative read in a modest-sized, though wide-ranging, book’, Honest History, 10 September 2019

Steve Flora reviews Castaway: The Extraordinary Survival story of Narcisse Pelletier, a Young French Cabin Boy Shipwrecked on Cape York in 1858, by Robert Macklin

As a reader with an inherited Euro-North American prism through which to view the world, I confess the need for something familiar to entice me to journey into other cultures. A familiar hook is a European lost on a distant shore and whose story reveals new information leading to an expanded appreciation of another culture (echoes of Swift’s Gulliver technique). Macklin’s work on the life of Narcisse Pelletier provides all this and more on multiple levels.

Prima facie, this is the story of a young person who, when betrayed and abandoned by one of his own people, is shown mercy and acceptance by ‘savage heathens’ who give him the opportunity of a new life. He is a real Robinson Crusoe with documents and photographs and scarring to prove his tale, which is a bridge between a lost Aboriginal world and the present for those of us that need such.

Prima facie, this is the story of a young person who, when betrayed and abandoned by one of his own people, is shown mercy and acceptance by ‘savage heathens’ who give him the opportunity of a new life. He is a real Robinson Crusoe with documents and photographs and scarring to prove his tale, which is a bridge between a lost Aboriginal world and the present for those of us that need such.

By intertwining the work of other historians, personal observation, original research and primary documents going back to Narcisse Pelletier, or Amglo (Pelletier’s Aboriginal name), this work is more than just the story of a 19th century castaway. The book presents an eye-opening history of European encroachment and ultimate takeover of what has become known as Queensland. Macklin also includes a quite detailed (if unedifying) history of the Native Police Force in that state. Simultaneously, through the experiences of the young Narcisse/Amglo, he reveals the story of the ways of life of the Aboriginal native peoples of the region before and during the early stages of the European takeover.

Castaway is an addition to the collection of histories of Europeans becoming dependent upon the original inhabitants of various lands and being shown much better treatment than a stranger in more ‘advanced’ societies could expect. Ultimately, the story is a tragedy, both for Narcisse Pelletier and for the Aboriginal people he came to know. In becoming part of the tribe, he lost touch with his original life and culture, even when he was eventually reunited with them.

As well as Macklin’s braiding together of the strands of both personal, regional and national histories, he has produced a substantial document recording the course of the Frontier Wars which flared across much of Queensland for nearly 75 years. A clear description of the course and effectiveness of the divide and conquer strategy used in Australia and most other colonial settings is part of the narrative.

Macklin’s work could have also been subtitled ‘Contrasts’ as, from beginning to end, it addresses contrasts between cultures, world views, personal ambitions, virtue and greed. Alternating chapters present the passage of time from Narcisse/Amglo’s point of view and that of the more impersonal historical perspective.

There is even a brief reveal of mid-19th century French social and political history from the stories of Narcisse/Amglo’s French family members. The castaway’s experiences during 17 years with the ‘Night Island People’ are similarly used to present the social customs of the Aboriginal inhabitants of the northern coastal area of Queensland. That adds up to multiple points of contemplation regarding various areas of the world, all encompassed in a modest- sized book.

Macklin packs in a lot of information but does not overdose, one example being an interesting note about Booby Island which was ‘where a permanent iron box was held fast to a rock. It contained letters deposited by passing ships of all nations to be conveyed to their respective addresses by succeeding vessels.’

There are almost poetic descriptions of the geography and cultural sites of northern Queensland. These lend a strong literary aura to the history and are blended with a skill lending greater depth to both. The second chapter is almost an ode to the landscape and its Aboriginal peoples.

Castaway does not neglect to mention those European settlers who did try to cooperate and live with the native peoples of the region, with the story of the Archer family of Durundur Station and the mutually supportive Dalla people a highlight. Unfortunately, such instances are rare in the context of the forced replacement of one culture by another, a process not encouraging of understanding and empathy.

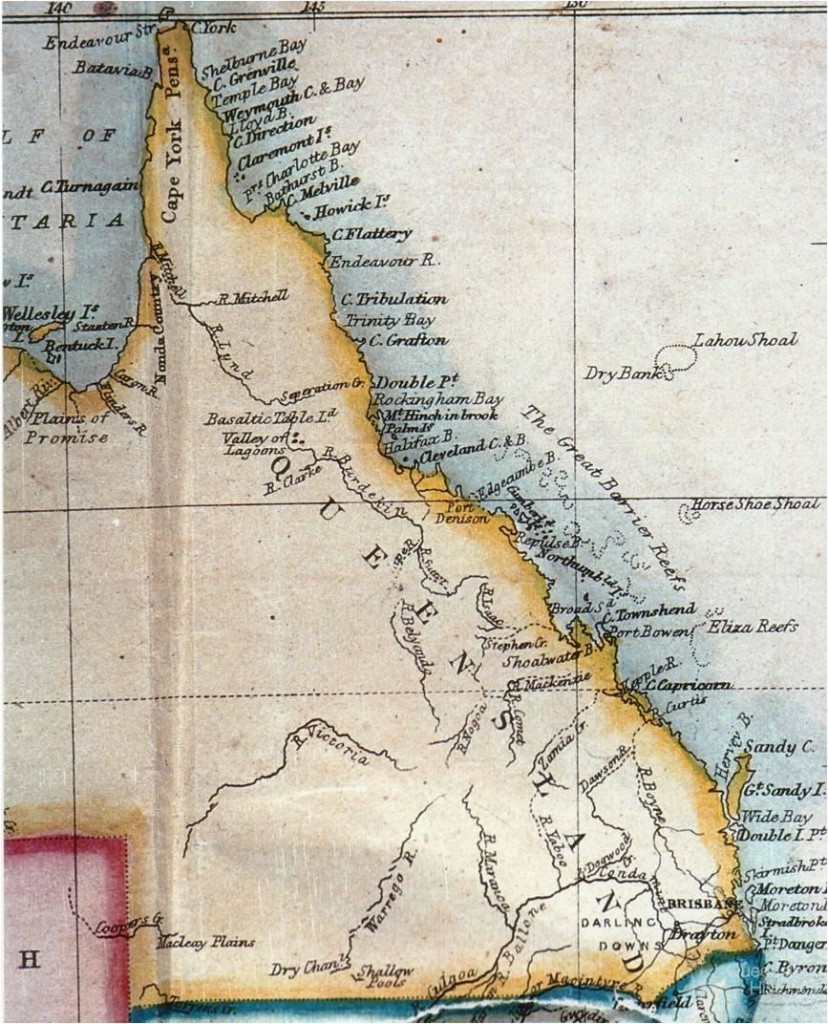

Edward Stanford’s map of Queensland 1861 (Queensland Historical Atlas)

Edward Stanford’s map of Queensland 1861 (Queensland Historical Atlas)

If there is a criticism of the book, it can stem from wondering just how much of the thoughts and feelings of Narcisse/Amglo are supported by primary texts and how much is mere speculation and projection by the author. How much did Pelletier say or think and how much is supposition? The true history can be devalued as a result. Macklin’s good intentions are evident, but does the wish to burnish the story overpower the facts? It is a possibility that Macklin himself confronts in his opening ‘Author’s Note’. Perhaps that is one of the inherent dangers in the presentation of what would, I imagine, be labeled as a ‘popular history’.

In this case, the book earns the adjective ‘popular’ because it is a well-written, interesting story that presents thoughts about the interaction of individuals and societies, valid in any time or place. Most readers might find these to be truisms, while perhaps for others they might be new revelations. Any work which tries to spread such enlightenment is vital in this time of increasing tribalism in many parts of the world.

On this reader’s bookshelf, Macklin’s work can certainly stand as a companion to Robert Hughes’ The Fatal Shore (1986), due to its historical basis, and to Bruce Chatwin’s The Songlines (1987), for its focus on often overlooked Aboriginal worldview concepts and traditions. Such oversights can happen both in Australia and elsewhere, where divisions between peoples result in misunderstandings, a scarcity of empathy and retreats into social enclaves. Histories of the clash of cultures often highlight not only what is regrettable, but also what is to be valued, what needs improvement and what should be used as inspiration.

Macklin’s Castaway contains numerous themes to contemplate and history to absorb. It is an addition to the Australian story and beyond.

* Steve Flora is the researcher behind Honest History’s Jauncey’s View series. He previously reviewed a book about maps and one about a mutiny.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.