‘A Museum of Australian Policing: That’s a good idea, but what stories will it tell?’, Honest History, 9 April 2022

In one of the flurry of pre-Budget news drops, the Home Affairs Minister, Karen Andrews, announced recently that the Federal Government will commit $4.4m to fund a ‘Museum of Australian Policing’. Her press release boasted of this as an ‘Australian first’. Literally that may be so, although there are already a number of Australian police museums that have been telling policing stories for some time (Brisbane, Melbourne, Sydney).

At the price tag of $4.4m I don’t expect we will be seeing much of a building; that benchmark has been set by the $500m dedicated to an un-needed redevelopment of the Australian War Memorial. But the announcement of a new museum prompts a more important question: what stories will this museum tell, or will it remain stuck in the familiar narrative of ‘investigative triumphs’, as trumpeted in the Minister’s press release?

A decade ago, at a time when health and politics still allowed a relaxed visit to China, I visited the Beijing Police Museum. It’s self-evident propaganda value notwithstanding – it’s always easier to see these things in a location other than one’s own – the museum is not a bad way to get a sense of modern policing, and some of the transitions along the way.

A corner of the Beijing Police Museum (koryogroup.com)

A corner of the Beijing Police Museum (koryogroup.com)

By Chinese institutional standards the museum is described as small. But it’s still four storeys of exhibition halls, displaying an impressive range of artefacts, behind an imposing Western classical façade with four massive Ionic columns. Two motifs stand out: the triumph of criminal investigations and the achievements of Beijing municipal police in maintaining public order. The six-metre high sculptured ‘Column to the Soul of Police’ is a signal that ‘the People’s Police are the atlas to support the security and the peace of the People’s Republic of China’. The eight by 18 metre ‘Memorial Wall to the Martyrs’ is a dedication not to the citizens lost at Tiananmen in 1989 but to the ‘public security martyrs’ of the Beijing Police. A first day cover bearing the signatures of ‘public security delegates’ to the Fifteenth National Congress of the Communist Party of China is another reminder that this is a museum of a particular kind of policing, whatever its investigative and preventive methodologies may share with other modern police.

So, what kinds of stories will this ‘first’ Museum of Australian Policing tell? If we really want to understand investigative triumphs, we also need to know about the conditions that make them so. These include the rules of law that govern evidence and its exclusion, the fallibility of technologies that purport to tell the truth, the techniques of interrogation that produce truth as well as error. And, since all these things are shared across modern policing, we can’t know anything about their distinctively ‘Australian’ character unless we know about the kind of police we have, how they are governed, whether and to whom they are accountable, and what we can do when things go wrong in law enforcement.

Will it help us understand the process of interrogation better if we know that the Western Australian Attorney-General prosecuting Yungala for murder in 1881 threw in the case after discovering that a ‘voluntary statement’ had clearly been coerced – ‘you tell them what to say and then they say it – is that it?’ he asked the arresting constable.

How will the Museum tell the story of ‘third degree’ tactics in Australian criminal investigation – the sort of stuff made famous in American movies? Those tactics were brought to account in an inquiry by Federationist and constitutional lawyer, Sir John Quick, in a 1930 hearing of disciplinary charges against a Canberra police sergeant. The sergeant was dismissed over evidence of his ‘good cop, bad cop’ routine in a brutal extraction from a 20-year-old youth of a confession to a minor stealing offence.[1]

Darryl Beamish, Estelle Blackburn (supporter and advocate) and John Button at the Supreme Court of Western Australia celebrating Beamish’s exoneration on 1 April 2005 (44 years after conviction), following Button’s exoneration on 25 February 2002 (39 years after conviction) (Wikipedia)

Darryl Beamish, Estelle Blackburn (supporter and advocate) and John Button at the Supreme Court of Western Australia celebrating Beamish’s exoneration on 1 April 2005 (44 years after conviction), following Button’s exoneration on 25 February 2002 (39 years after conviction) (Wikipedia)

What will the Museum make of the false conviction and long imprisonment of New South Wales man Frederick McDermott, that came to an end only when a Royal Commission concluded that the trial had miscarried, in spite of confirmation by the High Court; or of Darryl Beamish, the deaf mute Western Australian man who served 15 years for a crime he didn’t commit, the conviction quashed more than four decades late in a stunning reversal for police investigators?

What room will the Museum have for the story of Arrernte man Rupert Max Stuart leading to his capital conviction in 1959 on the basis of confessional evidence, resulting in a death sentence only set aside after vigorous civil society agitation that challenged the reliability of such evidence? Will the Museum help explain to its visitors the triumph of investigation that produced a conviction of Lindy Chamberlain, and the means by the triumph was reversed? What story will it tell there of the use of forensic evidence, driven by the confirmation bias of investigating police and a prosecution team, that a mother must be guilty of an infant death, in spite of plausible alternative explanations?

And will we learn how it was that a court of appeal in Western Australia in 2020 was able to find that Scott Austic had been convicted in 2009 and served 12 years imprisonment on evidence that showed ‘credible, cogent and plausible evidence’ of being planted?

Will the Museum of Australian Policing help us to understand these things? It should – but it’s not a good start when we are offered at the outset tabloid stories of ‘triumphant investigations’. If it is a museum worthy of the name in a democratic society it will find a way to tell stories of failure as well as success – and importantly how a free society can bring bad stuff in its own institutions to light, and to account.

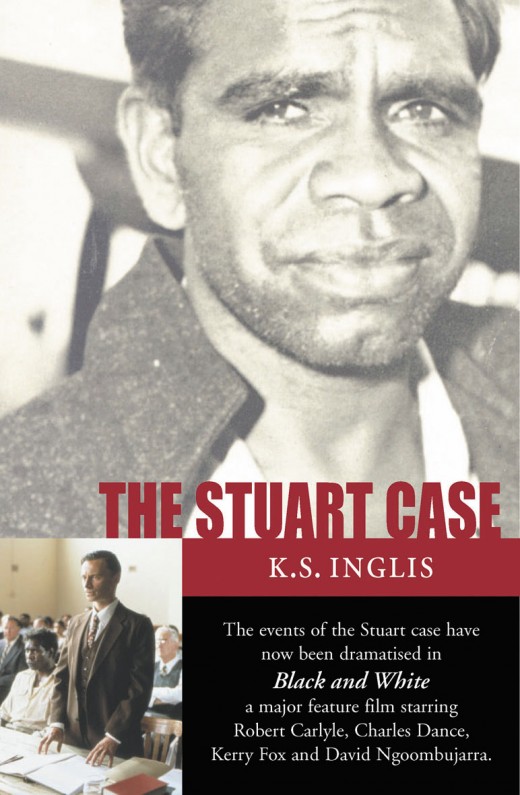

Cover of 2002 edition of Ken Inglis’s 1961 book, The Stuart Case (Black Inc.)

Cover of 2002 edition of Ken Inglis’s 1961 book, The Stuart Case (Black Inc.)

*Mark Finnane is Professor of History at Griffith University and Director of the Prosecution Project at that university. Among other positions, he was a Chief Investigator in the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence in Policing and Security (2007-13) and was Director of that Centre in 2009. He is the author of more than 100 articles and books on policing, punishment, and criminal justice.

Endnote

[1] Mark Finnane, ‘The third degree’, 41 Criminal Law Journal (2018), 295.

Yes, so many possibilities of what COULD be exhibited and dissected and explored beyond such an institution just being a display space for uniforms, weapons, handcuffs and tasers. But (just like the AWM) I imagine that the hard and structurally embarrassing aspects of Australian law enforcement history will be avoided.