ISSN:2202-5561 © Honest History Inc. 2013

Neither rosy glow nor black armband – just honest

Honest History: what’s it all about?

‘There is much more to Australian history than the Anzac tradition; there is much more to our war history than nostalgia and tales of heroism. Honest History is being set up to get those two messages across.’ This was the key point in our first e-newsletter in May.

This e-newsletter further introduces our website, Honest History, which we plan to launch later this year at www.honesthistory.net.au . Meanwhile, our e-newsletters will keep readers up to date with the development of the website and associated activities and give a taste of the sort of material we hope to include on the site.

This edition of the newsletter is located on a ‘raw’ version of the site. We have already loaded basic content onto the site but still have lots of work to do to load dozens of references and extracts into the Resources section before launching the site proper, we hope in November. You can find our first two newsletters here (No. 1) and here (No. 2).

Just as memory validates personal identity, history perpetuates collective self-awareness. (American historian, David Lowenthal)

Honest portrayal of the POW experience

Peter Stanley says there is a lot more to war history than stories of blokes in khaki fighting battles in faraway places. Being a prisoner of war seems about as remote from fighting as you can get. As the German soldier says to the captured British Tommy in the 1968 POW movie, Hannibal Brooks, ‘Zee war for you is over!’

The non-warlikeness of POW life is one reason why this part of our history has been neglected. This was a key message from the conference, ‘Prisoners of war: the Australian experience of captivity in the 20th century’, held in Canberra on 5-6 June. The conference was sponsored by the Commemorations Branch of the Department of Veterans’ Affairs and organised by Professor Joan Beaumont and her colleagues at the Australian National University, in collaboration with the Australian War Memorial. More than one hundred people attended.

The twenty or so conference presentations threw light into some dark corners of POWdom, politely shattered some myths and revealed some unsavoury facts. All of the papers were strong on archival and other evidence, as myth-busting needs to be, even though the original myths are usually remarkably evidence-free.

A highlight was the paper from Seumas Spark (Monash University) which exposed an official World War II army policy on repatriated Australian POWs of the Germans and Italians. Surrender rather than death was dishonourable, according to General Blamey, even if sometimes surrender was inevitable. While this view was not publicly expressed, the army hierarchy did all it could to avoid publicising the returned POWs for fear that people would regard them as heroes.

Australian ex-prisoners of war go home ca. 1945 (source: © State Library of Victoria image H98.103/4187 via Trove)

Christina Twomey (Monash University) reported that 1950s Australian attitudes to compensation for POWs of the Japanese were affected by official views that the prospect of compensation payments might discourage soldiers from continuing to fight and that actual payment might be seen as rewarding those who had given up too soon. Other speakers mentioned the embarrassment, even shame, felt by POWs at the time of captivity and after.

Aaron Pegram from the Australian War Memorial skewered the legends of escapes from German POW camps in World War I, pointing out that only 39 Australian POWs (or less than one per cent of Australians in the camps) and an even lower proportion of British prisoners escaped. Only two of the Australian 39 returned to the front after escaping. (These findings come from Aaron’s Ph. D research; meanwhile, he has been appointed Historian, First World War Centenary Projects, at the Memorial.)

Melanie Oppenheimer (Flinders University) and Kate Walton (University of Queensland) showed how POWs’ families relied on the Red Cross to provide news of their loved ones and to convey comforts and food to them. Kate also described the role of a global network of POW families in exchanging news.

Joan Beaumont presented evidence that Australian officers fared better on the Thai-Burma railway than other ranks; officers had positioned themselves within the Anzac legend but the privileges of officers sat uneasily with the egalitarian elements of the myth. Australians and British prisoners on the railway died at about the same rate.

Lucy Robertson (University of Adelaide) explored crime in Changi prison and how officers’ efforts to preserve law and order damaged officer-other ranks relations. Jennifer Lawless (New South Wales Board of Studies), Peter Monteath (Flinders), Peter Stanley (Australian Defence Force Academy) and others presented many interesting aspects of the POW experience while the conference also heard from Korean War POWs, Ron Guthrie and John MacKay, and oral history pioneer, Tim Bowden. Australian War Memorial Director, Brendan Nelson, gave a spirited address over dinner.

It was especially inspiring to hear from so many younger historians, focusing forensically on a part of our national story that has lacked this type of scrutiny. Honest history is in good hands.

Eureka: have we found it?

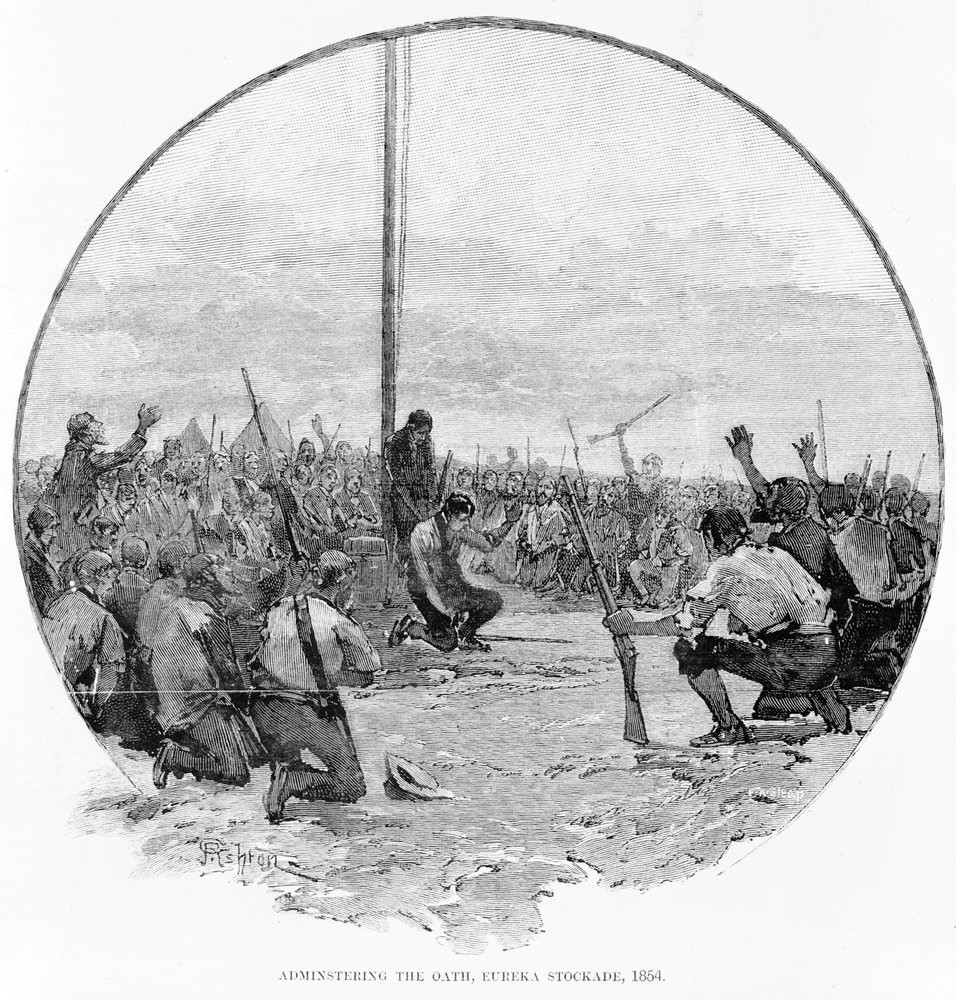

The forces of law and order killed more white civilians at Eureka than in any other incident in our history. Perhaps that explains why the attention paid to Eureka has ebbed and flowed so conspicuously since 1854. Eureka has been an awkward part of our national story. Does it deserve a larger place?

Administering the oath, Eureka Stockade, 1854: wood engraving by FA Sleap,, 1888 (source: © State Library of Victoria image IAN01/08/88/supp/16 via Trove)

The brief battle at Ballarat on the early morning of 3 December 1854 claimed the lives of at least 22 diggers and five troopers. The colonies lived uneasily with what had happened. By 1904, however, distance allowed HG Turner in his A history of the colony of Victoria to give a detailed and balanced account, recognising the impatience of the miners along with the ‘admitted injustice’ they suffered and the ‘brute force’ employed against them.Thirty years later, though, LC Jauncey (The story of conscription in Australia, published in 1935) complained of Eureka that ‘this important phase of Australian history has slipped out of sight’ when it should have been a model for battles against authority. By 1962, Marjorie Barnard in A history of Australia dismissed the events at Ballarat in two pages, concluding that ‘[a] great deal, perhaps too much, has been made of Eureka. . . The pathetic little rebellion was a very minor occurrence. It was heroic and doomed to failure.’ TH Irving in A new history of Australia (edited by Frank Crowley, 1974) also managed only a few paragraphs.Manning Clark devoted more than a dozen pages of his A history of Australia (Volume IV, 1980) to Eureka but was ambivalent about its significance. Democratic tendencies on the goldfields had led to fear in the cities and the miners’ ‘dream of a glorious future for humanity had fallen on stony ground in Australia’. On the other hand, Thomas Keneally (Australians: origins to Eureka, 2009) used the rebellion to mark the divide between his volumes, painted cheerful pen-pictures of those involved and concluded that Eureka and the concessions it drew from government amounted to ‘an exhilarating time for Australian patriots’.

What then are we to make of Eureka? Clare Wright has written extensively on the events at Ballarat and is about to publish The forgotten rebels of Eureka, about the women of the rebellion. In 2006, she compared Eureka with Anzac

The problem with Eureka – what makes it such a thorny perennial – is that the combat was between us and us. Civilians took up arms against the state. . .

So will we ever celebrate Eureka Day? Come the republic, perhaps. But it’s plain to see why Gallipoli is a magnet for conservative politics and Eureka is a lightning rod for nonconformist causes. Where the Anzac legend supports paternalistic nationalism, Eureka symbolises independence of thought and action. Where the Australian government and armed forces were longing for imperial recognition of their valour on foreign battlefields, the goldfields population were self-consciously making their own destinies. . .

We would do well as a nation, respectful of the past and hopeful for the future, to ground our collective self-awareness in multiple, complex histories.

I would like to live in a country that is courageous enough to do that.

So would most of us. ‘Multiple, complex histories’ is just what Honest History supports.

I believe that the 1854 Eureka Rebellion – a collective uprising against oppressive taxation – should be reclaimed by both sides of politics as our driving legend. (Andrew Leigh MP, Battlers and billionaires (2013))

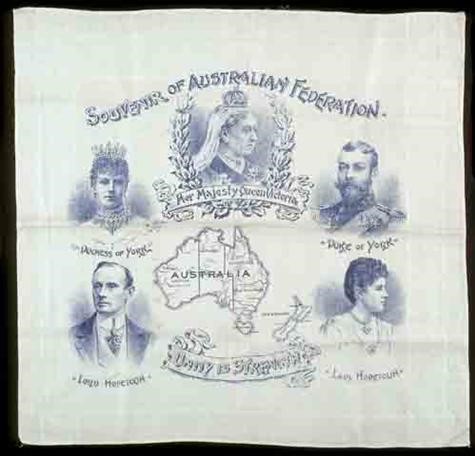

What was the dream, federationally speaking?

Chris Masters, in his recent ABC program, The years that made us, said that World War I destroyed ‘the Federation dream’, which he described as ‘a fair go nation with equality for all’. What did the Australians of 1901 think? Did they have a dream, what was it and what happened to it? We’ll start with some newspaper editorials from January 1901. They reveal pride and a recognition that a new nation had been born, albeit a British one. ‘The greatest day in Australian history has come and gone, and yesterday a new power was added to the galaxy of nations’, said the leader writer of the Goulburn Herald, and there was this from the Adelaide Advertiser : ‘Six self-governing colonies, by a voluntary act, and on lines laid down by themselves, are welded into a nation, one of a family of nations that compose the British Empire’.

‘First and foremost’, agreed the Melbourne Argus, ‘the Commonwealth embodies the matured resolve of the people of Australia and Tasmania to become one nation under the British flag. Much further north, the Morning Post in Cairns reported local feelings.

A national spirit was thoroughly aroused, and one and all, young and old, appeared to realise that they had taken an important stride amongst the nations of the earth, advanced still higher the honor and importance of the Empire, and at last achieved the goal for which the ablest leaders in the land had striven for the past twenty years.

‘We enter on the new year and the new century a united Australian nation’, summarised the Sydney Morning Herald, devoting a number of closely-printed pages to describing the new nation. Under the heading, ‘The occupations of the people: general conditions’ and drawing on the work of the New South Wales government statistician, TA Coghlan, the paper described changes in the years since 1880: all classes enjoying material comforts to match those found in the best American and European cities; easy and cheap communication in cities; salaried classes better paid than in Britain and tradesmen’s wages comparing favourably; two-thirds of tradesmen working the eight hour day; minimum wage rates in several colonies; distribution of wealth and property unparalleled elsewhere in the world; low unemployment.

Handkerchief – Australian Federation, Linen 1901 (source: ©Museum Victoria, reg. no. SH001011, via Trove)

The Herald concluded: ‘That life may always be as pleasant, as hopeful, and as prosperous for the masses under federation in the years to come as it seems to be at the birth of our great and promising nation is a desire that every patriotic Australian must surely entertain.

What did the Great War do to the new nation’s dream? How did the 1901 rhetoric about the birth of a nation within an Empire compare with the rhetoric attending the Gallipoli landing in 1915? We’ll look at these issues in Honest History.

All years make us who we are. . . History favours the dramatic. It’s so much easier and attractive to tell stories about what happens on battlefields. . . Australia is framed by war rather than forged in war. . . Anzac is important but it’s not the only story. (Chris Masters, The Drum , ABC, 21 June 2013) See also here.

When America looked to Australia: HB Higgins and the minimum wage

Australian history has not always been about our need to retain great and powerful friends. There have been times when the rest of the world looked to us as a role model and pioneer. A new article from Marilyn Lake traces the important role of Henry Bournes Higgins in pioneering minimum wages and places him firmly within an international Progressive tradition prior to World War I.

HB Higgins (1851-1929) (source: Australian Dictionary of Biography: NLA pic an 21399820-39, Australasian Federal Convention, Melbourne, 1898)

Lake sees Higgins as ‘a key participant in the reciprocal intellectual exchanges that defined the transnational Progressive world of labour reform’ in the years after his ‘Harvester Judgement’ case in 1907. Higgins visited the United States in 1914, meeting jurists Louis Brandeis, Felix Frankfurter, Learned Hand and Roscoe Pound, social activists Elizabeth G Evans, Josephine Goldmark and Margaret D Robins, President Wilson, former President Theodore Roosevelt and other luminaries.

Higgins’s article for the Harvard Law Review, ‘A new province for law and order’, was influential in US legal circles. Goldmark, researching for Frankfurter, advised him that ‘[t]he best examples of the benefit to society and to workers arising from the short workday are found in Australasia’.

Higgins’s work was reflected in US cases down to the adoption of the minimum wage as federal law in the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 under President Franklin Roosevelt. ‘More generally [Lake writes] Higgins’ innovative jurisprudence encouraged the work of Brandeis, Frankfurter, Holmes, Pound and others in developing a “new body of law” in industrial relations that would put “the human factor in the central place”.’ (The internal quotes are from Pound.)

Higgins resigned from the Commonwealth Arbitration Court in 1920 after a dispute with Prime Minister Hughes over the Court’s jurisdiction. Frankfurter had written to Higgins in 1917 that ‘the great work you have done establishing traditions and a body of experience will survive’ and in 1918 Frankfurter wrote in the New York Times of ‘the experiments and legislation’ of ‘progressive countries’ including Australia.

Lake’s own comment is less sanguine.

The war was. . . destructive for Australia as a nation, which lost not only many thousands of its young men [including Higgins’s own son], but a sense of itself as an independent pioneer in passing advanced legislation, succumbing instead to the revitalised forces of conservatism and imperialism. Higgins was despondent. “Hughes is ruining our Australian experiments”, he lamented to Frankfurter in 1921.

The impact of World War I on Australia is a key concern of Honest History. We are interested in not just what Australians did in the war but what the war did to Australia and Australians.

Of course, war does often help nationality; so would the eating of babies satisfy hunger. (HB Higgins to Felix Frankfurter, 12 December 1914)

Darwin bombing keeps on giving: commercialised commemoration

The newish Director of the Australian War Memorial, Brendan Nelson, reckons that 1942 is one of the two most significant dates in Australian history. He may well be right, to judge by the articles in Australia 1942: in the shadow of war, edited by Peter J Dean and published earlier this year by Cambridge University Press. The articles in the book describe Japan’s plans, the Allied response and the tense atmosphere in Australia in that crucial year.

Most interesting for this reviewer was Alan Powell’s piece on the Darwin air raids of February, 1942. Powell shows how the commemoration of this event has been woven into the fabric of Territory history and, specifically, into its tourist industry. He considers commemorations in decade intervals from 1942. In 1952, there was a brief ceremony. Ten years later, the Northern Territory News reported a ceremony attended by just 200 people. By 1972, the numbers were down to 100.

The change came after Territory self-government in 1978. In 1982, the Territory government organised a much more elaborate ceremony and, Powell notes, the theme of the commemorations by this time had become the heroism of locals rather than the panicked shambles that had marked the original event. This trend continued through the nineties.

In 2002, the sixtieth anniversary of the raids, the Territory government assisted 800 veterans and their families to visit Darwin, with commensurate benefits to local business. Ten years later, in 2012, the commemoration reached new heights, with the government putting $10 million towards building a multi-media ‘Defence of Darwin experience’ (plus smart phone app), forty commemorative events, including a black-tie ball, a commemorative AFL match, and ‘A minute’s warning: a one-off wearable art production showcasing creations inspired by the bombing of Darwin’. Not surprisingly, the then prime minister responded by making 19 February a new ‘national day of commemoration’.

‘Apart from the five commemorative ceremonies’, Powell concludes, ‘nearly all of the planned events were principally concerned with tourism, commercial opportunity and/or politics’. There is much more to commemoration in the Top End than the ‘perpetuation of ritual’. Might the same be said of other commemorative exercises elsewhere?

But wait, there’s more. . .

Jack Waterford has written trenchantly in the Canberra Times about the growth in the Gallipoli souvenir industry, everything from shavings of the Lone Pine to ‘the Legend of Gallipoli watch’, in a limited edition of 1915 copies at $399.50 each, complete with inscription ‘Australia was born on the shores of Gallipoli’ and image of John Simpson Kirkpatrick (whose exploits were recently reduced to human dimensions by people not connected with the souvenir industry).

For the more cashed up, however, there are tours on luxury liners which will stand off Anzac Cove at dawn on Anzac Day 2015. Imagine experiencing the breaking of dawn at Gallipoli …’, advertises one tour, costing more than $15 000 per person. ‘This is Anzac Day, on the shores of Gallipoli, where our soldiers sacrificed their lives for ours, exactly 100 years before.’

This tour operator has signed up former Chief of Army, Ken Gillespie, and former Chief of the Defence Force, Chris Barrie, to provide the commentary. ‘Drinks are complimentary whilst onboard, your suite’s fridge will be stocked to your taste.’ There is no indication yet whether Victoria Bitter and its former CDF are running a rival venture.

Using and abusing history

The use and misuse or abuse of history will be a strong theme of Honest History. We condemn the abuse of history but we vigorously support its honest use to support policy options.

‘Honest history is the weapon of freedom’, allegedly said Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. (One could compare this aphorism with American policy since 1990.) Schlesinger’s fellow dweller in John Kennedy’s Camelot, Richard E Neustadt, co-authored Thinking in time: the uses of history for decision makers. Richard Nixon (according to Henry Kissinger) wandered the White House at night, conversing with the portraits of his predecessors, seeking tips.

More recently, a new biography of Vladimir Putin describes him as ‘the man who rifles Russian history for inspiration’. Observers made similar remarks about the John Howard whose father and grandfather fought on the Western Front and the Paul Keating who revered Kokoda and lost an uncle at Sandakan.

In June, David Mathieson wrote an article for The Guardian about the politics surrounding a memorial in Madrid to the Spanish Civil War and claimed, ‘Explaining the past to shape the future is a basic tenet of any mature political process’. Meanwhile, the Erdogan government in Turkey is reshaping the Gallipoli story as an Islamist crusade.

Mathieson oversimplifies. Prior to explanation comes fact selection and interpretation. Use becomes abuse when leaders and governments distort and embellish facts to suit current political purposes. The American anthropologist, Paul Shackel, says, ‘Public memory is more a reflection of present political and social relations than a true reconstruction of the past’. Shaping the past helps shape the present and the future. A political process where that happens frequently is not mature, as Mathieson claims, but just crafty.

Young people and the Anzac tradition today

Young Australians have differing views on Anzac and related matters. Robert Selth asks in Woroni, the student newspaper of the Australian National University, ‘Is there not something harmful in the way we increasingly require acknowledgment of the ANZAC “spirit” as an essential component of Australian identity?’

Tom Joyner from the University of Sydney writes, ‘As long as we still dogmatically bandy around the tired emblem of the ANZACs, it certainly won’t be the last time Australia is led blindly into the kind of conflict better left to countries who still don’t think the Vietnam War was a mistake.’

Meanwhile, the Department of Defence runs an annual youth challenge for senior high school students. Participants in 2012 were asked, ‘Has the ADF [Australian Defence Force] helped shape Australia’s national identity?’ In 2010, participants had considered whether ‘the Spirit of Anzac’ is ‘relevant to the ADF and society today’. They agreed

that the Spirit of ANZAC, born at Gallipoli in 1915, still has a great deal of inspiration to offer us – though there are elements of it that need to be adapted and changed to meet modern times. . . However, core values such as courage, mateship and determination still retain their value as civic virtues we can all aspire to today, and which help us create a better society.

Honest History wants to explore the attitudes of young historians and young Australians generally to aspects of our history, including Anzac.

Freedom’s call resonates still

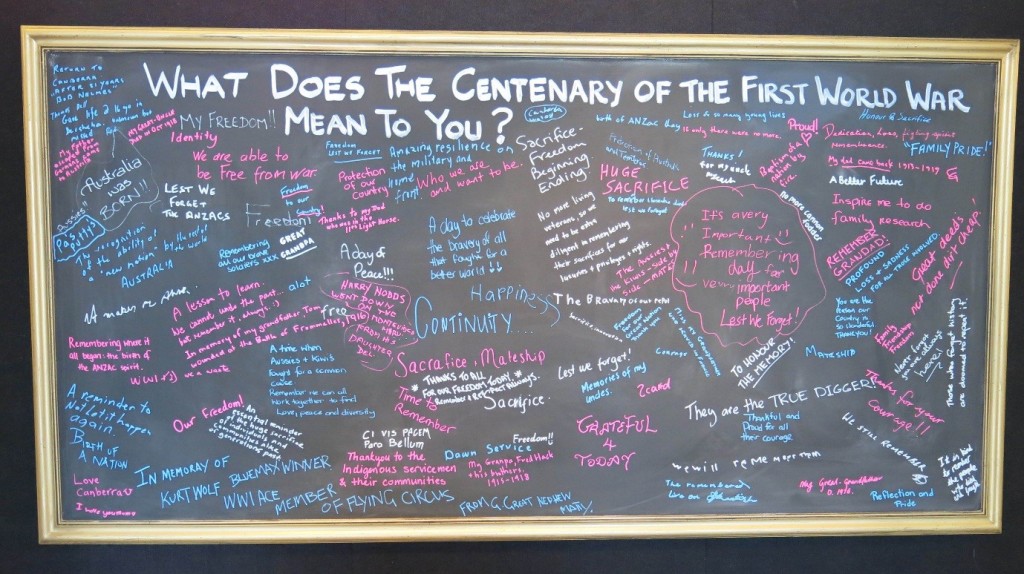

One phenomenon Honest History hopes to explore is how geopolitical (or just political) reasons for going to war are transformed, apotheosised into more abstract, sublime justifications, especially after the event and for the comfort of the participants and their often bereaved families. ‘Freedom’ features frequently in these exercises, even though pragmatically it is difficult to argue that Australia invading, say, the Ottoman Empire in 1915 or Iraq in 2002 had much to do with our freedom.

The illustrations below suggest, however, that freedom’s call still resonates. The text on the medallion is ‘He died for freedom and honour’. The second illustration is notable for the number of times the word ‘freedom’ appears.

Medallion sent by the King to the families of all service people in World War I (private collection, family of Captain SJ Campbell, 8th Light Horse, died of wounds, July 1915)

Blackboard at the Australian War Memorial open day, 6 April 2013, containing opinions of adults and children (source: ©AWM website)

Anzac Centenary Local Grants

It is not too late to try to influence the mechanisms by which $100 000 is being allocated to each Federal electorate to commemorate the centenary of Anzac. Those interested should first check out the process, including guidelines, then get in touch with their local MP to see where things are up to in the electorate. While the bias of committee memberships is likely to be towards RSL representatives, it might just be possible to influence the direction of projects in the direction perhaps of less bricks and mortar and more meaningful commemoration, even something really useful like a commemorative donation to Soldier On.

‘After all, this is a fantastic opportunity to be part of re-shaping Anzac Day’, says Honest History supporter, Sabina Baltruweit of Remembering and Healing, a peace group based in Lismore, ‘to have in-depth dialogues with the RSL of what it should be, and with all this changing the culture, at least make it more inclusive and fit for the 21st century. I don’t think there will be another opportunity like this for many years to come.’

In future e-newsletters and on the website: more on using and abusing history, Eureka, Federation, the National Curriculum, Constitution Day, DVA’s education program in comparative context, who is deciding the Anzac commemoration handouts, the windows in the Hall of Memory, Great War commemoration plans in the UK, memorials and memorialisation here and there.

Growing Honest History

Honest History’s support grows

Honest History has received the support of many distinguished historians and other Australians, among them Frank Bongiorno, Judith Brett, Ann Curthoys, Paul Daley, Joy Damousi, Tom Griffiths, Marilyn Lake, Stuart Macintyre, Mark McKenna, Peter Stanley, Christina Twomey, Ben Wellings, Clare Wright and many others.

This e-newsletter is going direct to 200 addresses (compared with 86 for our first edition) and we know it is being sent on to at least 170 other people. Please send it on and/or encourage people to give us their direct email address. Also, please let us know of like-minded organisations and networks with whom we should link up.

Honest History Incorporated

Michael Piggott has joined Honest History’s committee as Treasurer. He was University Archivist and Manager, Cultural Collections Group, at the University of Melbourne 1998-2008 after senior appointments at the National Archives of Australia, the Australian War Memorial and the National Library. He is the author of, among other mostly archival writing, A guide to the personal family and official papers of C E W Bean (Australian War Memorial, 1983), The coconut lancers: a study of the men of the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force in New Guinea, 1914-1921 (B Litt thesis, ANU, 1984) and most recently Archives and societal provenance: Australian essays (Chandos, 2012).

Meanwhile, Honest History is now an incorporated association (Honest History Inc.) under the Associations Incorporation Act 1991 (ACT). We will be known by our business name Honest History. Our inaugural committee is Peter Stanley (President), Richard Thwaites (Vice President and Webmaster), David Stephens (Secretary and Public Officer), Michael Piggott (Treasurer), Marilyn Lake (member), Joy Damousi (member) and Sue Wareham (member). Biodata for members besides Michael is here.

Donations anyone?

Honest History now has a bank account. If anyone would like to make a modest donation to support the Honest History project, please advise us by email (address above) with the word ‘Donation’ in the subject line and we will tell you how to do it. More sophisticated arrangements are on the way. Donations are unfortunately not tax deductible yet but we are looking at options.

Honest History at the Australian Historical Association annual conference

The AHA held its conference in Wollongong early in July. The national executive committee of the AHA considered the Honest History project and agreed that the AHA supported the initiative and would like to be kept informed and that Honest History should send any items it wishes to be considered for publishing in the AHA newsletter. Meanwhile, Honest History has started to build links with state history teachers’ organisations.

The AHA was founded in 1973 and is the premier national organisation of historians – academic, professional and other – working in all fields of history. Its members number more than 800, including universities, libraries and other affiliates. (AHA website)

Like to write for us?

Got something to say that fits within the objectives of Honest History? Can you say it in 600 words or less? Send an email to us (address above) setting out your idea in 50 words and we will look at commissioning you to write for this e-newsletter. (No payment, sorry!) Include the word ‘Pitch’ in the subject line of the email. We will also be looking for longer articles (up to about 1200 words) for the website, to launch later this year.

History will be kind to me for I intend to write it. (Attributed to Winston Churchill)

Researchers needed

If you can find your way around the internet and would like to help with some research tasks for Honest History please send us an email (address above) with the word ‘Research’ in the subject line. No pay, just a sense of satisfaction.

Comments, feedback

Like to comment on something you have seen in this e-newsletter? Like to suggest something that you want us to cover? Please send us an email (address above) with the word ‘Comment’ in the subject line. Be polite!

Distribution policy

If you are receiving this e-newsletter it is because:

- we contacted you and you agreed to be placed on our mailing list or

- someone on our list has sent the newsletter on to you or

- we have heard ‘on the grapevine’ or deduced from your public output that you might have an interest in the enterprise.

If you know of anyone else who would like to receive the newsletter direct, please let us know (contact details below).

If you have had the newsletter sent on to you and would like to get a copy direct in future, email us (address above) with ‘Subscribe Honest History’ in the subject line.

If you would prefer not to receive the newsletter in future email us at admin@honesthistory.net.au with the word ‘Unsubscribe’ in the subject line.

David Stephens

Secretary

Honest History

1 August 2013