Barrie Dyster*

‘Grieving for Gallipoli: a reflection for the centenary of the 1918 Armistice’, Honest History, 23 September 2018

The centenary of the end of the Great War is an opportunity to reflect on the world-wide impact of the conflict. Romain Fathi recently placed the whole war in its international context; here Barrie Dyster does something similar for the Gallipoli campaign and links his argument to the future of Remembrance and Anzac Days as occasions for commemoration.

It should be obvious – but is frequently not appreciated in Australian official commemoration – that the years 1914-18 were important not just for Australia and Australians but for many other parts of the world and their people, as the literature shows. For example, Vicken Babkenian and Peter Stanley have written about the Armenian genocide, which began almost simultaneously with the 25 April invasion, while Stanley has written about Indians at Gallipoli. Ayhan Aktar has described how the Turkey of today is using the history of 1915.

British and Irish casualties at Gallipoli were almost three times Australian casualties and Ottoman casualties were nine times Australian casualties. And the words ‘Lest We Forget’ uttered in Australia do not always extend to New Zealanders at Gallipoli. Every child who visits the Australian War Memorial will hear that more than 60 000 Australian soldiers and sailors died in World War I but how many will learn that the war took the lives of almost seven million civilians and ten million military personnel world-wide?

An understanding of global impacts is what should come out of Remembrance Day 1918, says Barrie Dyster. More importantly, he asks, ‘will we be able to carry the global perspective of Armistice Day 2018 over into the Anzac Days of the future?’. Or will future 25 Aprils in Australia still be all about Us? HH

***

A significant event in 1990

Bob Hawke was the first Australian prime minister to lead a pilgrimage to Gallipoli. In 1990, he took 52 veterans of the campaign, along with about 60 journalists, to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the Anzac landing.[1] The ceremonies at Anzac Cove and at Lone Pine, however, were smaller than the third event that Hawke and his entourage attended on 25 April 1990.

Çanakkale Martyrs’ Memorial from beneath (Forgetyousawthis.blogspot)

Çanakkale Martyrs’ Memorial from beneath (Forgetyousawthis.blogspot)

The Çanakkale Martyrs’ Memorial at Cape Helles on the southern tip of the Gallipoli peninsula is an impressive structure visible from every Istanbul-bound ship that enters the Dardanelles. Here, on that Anzac Day nearly three decades ago, President Turgut Özal of Turkey played host at a meeting of former enemies. Margaret Thatcher flew from London to be present. The Governor General of New Zealand flew from Wellington. The French Secretary of State for Veterans’ Affairs was there. Troops from five nations – Turkey, Britain, France, New Zealand, Australia – stood at attention, as did detachments from India and from the newly united Germany. Canadian veterans travelled with the British delegation; a regiment from then-independent Newfoundland had served on the peninsula in 1915.

Mrs Thatcher attended for a reason: more than three times as many men died on Gallipoli wearing British uniforms as died in Australian uniforms.[2] France was represented because, by Jeffrey Grey’s estimate, ‘the French Corps Expeditionnaire d’Orient lost more dead than the Australians and New Zealanders combined’.[3] What impact, if any, has participation at this multinational event had on Australian official commemoration of Gallipoli in the 28 years since? What has been the effect, too, on the long-term reportage of the scores of journalists who came with Hawke?

Looking back to three events on 25 April 1915

The truth is that there were three substantial landings at daybreak on 25 April 1915, not just the one landing we Australians celebrate. The Anzac landing was not the biggest, the bloodiest, the most successful, or even the least successful of the three.[4]

The British came ashore at Cape Helles. Regiments from across England, from the Scottish borders, from south Wales, from three of the four provinces of Ireland (the Connaught Rangers turned up later in the year), waded through shelving water onto beaches strung with barbed wire. There were fairly clear sight-lines for the Ottoman defenders’ rifles and artillery. So many heavy-laden men failed to get through the shallows, the wire or across the beaches to partial shelter, that those commanding the Lancashire Fusiliers, aghast at the carnage and awed by the deeds of their comrades, recommended (successfully) the award of six Victoria Crosses. Six crew members of the naval vessel River Clyde also won VCs as they ferried soldiers to shore that morning.[5]

British troops at Gallipoli (Pinterest)

British troops at Gallipoli (Pinterest)

Meanwhile, troops under French command attacked a garrison at Kum Kale, directly across the Dardanelles from Cape Helles and near the site of ancient Troy. The French neutralised guns and shattered regiments that otherwise might have harried the British from the rear. Their task done, the tired French crossed the water only two mornings later to fight beside their allies at Cape Helles.[6]

A kilometre or so inland, the incursion at Cape Helles stalled. On 6, 7 and 8 May a renewed push came from the stalemated front line. It was called the Second Battle of Krithia, and the landing was then known in retrospect as the First Battle of Krithia. Krithia was a village further up the road to Istanbul. Indian, Nepalese, New Zealand and Australian troops joined in with the British, and with the African and European units that made up the French forces. (The English war correspondent Ashmead-Bartlett wrote: ‘I doubt whether, even at Leipsic [1813], so many different nationalities have been brought together on the same battlefield’.)[7]

There was no progress at Krithia; a third battle began a month later. Anzacs did not take part on that occasion, but British, French, Indian and Nepalese contingents tried again. After six more weeks, the invaders gave up; Krithia remained beyond reach. During that time, the artillery neutralised at Kum Kale had been replaced and the French, in particular, who occupied the Allied flank closest to the Dardanelles, were shelled regularly.

Remembrance in Britain and Ireland

Families far and wide across the British Isles mourned men who did not return from Gallipoli. That campaign was remembered by their fellow citizens, however, largely for the supposed incompetence of politicians and commanding officers. There had been so many military successes and failures in earlier centuries, and so many failures and successes soon to come, that the suffering of British soldiers on Gallipoli faded into the background.

Regiments that fought on Gallipoli did hold services of remembrance in the towns that housed their barracks. In Bury, above all, a mill town outside Manchester, the home of the Lancashire Fusiliers, the Sunday following 25 April was ‘Gallipoli Sunday’, when the Fusiliers would put on a two-hour military display before marching with local dignitaries and other civilians into the parish Church of England. And one of the peninsula chaplains, the vicar of Eltham, in London’s south-east, dedicated a side-chapel in his church to commemorate the campaign. He preached a memorial sermon each April.[8]

Irishmen had made up a significant minority of British forces. Unless the Irish returned to the six counties of Northern Ireland they did not enjoy the consolation of public honour, for the rest of Ireland had won its bitter independence once the War was over. The word ‘Gallipoli’ entered the lexicon of the Republic as a synonym for the heedless sacrifice of lives to the rejected Empire. It was only in the 1990s that President Mary Robinson authorised the formal recognition of those who served in the World War I.[9]

Many Australians also hold tenaciously to the contempt felt by many Britons and by the Irish for the quality of British leadership. Contempt often carries over into condescension, if ever a thought has been given, for the fighting men of the British Army. In view of this attitude, how can the scale of the British and Irish casualties be made in future an active part of every Australian ceremony on 25 April?

Remembrance in France

Toy soldiers in French Foreign Legion uniforms as at Gallipoli (PiersChristian)

Toy soldiers in French Foreign Legion uniforms as at Gallipoli (PiersChristian)

And then there is the French Army. Awareness of Gallipoli would be hard to find in France. The Western Front, understandably, has filled the nation’s horizon. Only a small number of Frenchmen, anyway, had been spared, or wished to be spared, from the battles at home. The majority (how large a majority?) of French troops on the peninsula were from Africa, some from North Africa, some from West Africa. Units of the Foreign Legion also fought at Kum Kale and later.[10]

Algeria had been prised away from the Ottoman Empire in 1830. Ever since the Crimean War, Algerian fighting units in the French Army had been nicknamed ‘les Turcos’. Tunisia became a French protectorate in 1881. Most of Morocco became a French protectorate only in 1912, but men from there sought employment in the French Army before that date. But as the historian John Horne has suggested, ‘despite initial plans it proved impossible to use [les Turcos on Gallipoli] … because they would be fighting against fellow Muslims and possibly occupying the holy sites of the Middle East’.[11] The one-third of the Corps Expeditionnaire d’Orient that came from North Africa was composed of European colonials settled in Algeria and Tunisia. Formal alienation and occupation of land in Algeria for use by Europeans coincided with the same process in Western Australia, Victoria, South Australia and New Zealand, whence many of the French troops’ Anzac allies were recruited.

Troops from south of the Sahara were called ‘Senegalese’. Dakar in Senegal had been an intercontinental trading port for several centuries. In 1895, the metropolitan power created a federation called French West Africa. The colonies of French Sudan (present-day Mali), Guinea and Cote d’Ivoire were joined with Senegal under a Governor-General resident in Dakar. In 1904, the colony of Dahomey (present-day Benin) was added to the federation, as were the ‘military territories’ of Mauritania and Niger. ‘Senegalese’ landed at Kum Kale on 25 April, and on the peninsula in the following days.[12]

The French Secretary of State for Veterans’ Affairs attended the 75th anniversary gathering at Cape Helles, but people representing African successor nations seem not to have been present. L’organisation internationale de la Francophonie has been an entity continuously since 1970. Algeria, independent after decades of mortal struggle, has no truck with the organisation, but Tunisia, Morocco, Senegal, Mali, Guinea, Cote d’Ivoire, Benin, Mauritania and Niger are members.[13]

Tunisia, Morocco and Cote d’Ivoire have embassies in Canberra (the nearest offices of other West African francophone countries are in Tokyo or New Delhi).[14] Their diplomats may wish to be included in Australian commemorations on Armistice Day, although only the West African countries have any reason to remember the Gallipoli landings on 25 April. And, although not very many immigrants have yet come to Australia from the Sahel and the Maghreb, would it not deepen our understanding of events to be reminded that Anzacs and Africans fought side by side at the Second Battle of Krithia, and for the rest of the year suffered equally on the peninsula?

Indians at Gallipoli

Indians at Gallipoli (SBS)

Indians at Gallipoli (SBS)

The 7th Indian Mountain Artillery Brigade came ashore at Anzac Cove that morning in April. It is thought that some of these men climbed further up the ridge by nightfall than anyone else as they searched for vantage points to place their guns. Indian units in various capacities – and Gurkhas – spent time with the Anzacs and in other sectors of the campaign. General Birdwood, commander at the Cove, was accompanied by the Ceylon Planters’ Rifle Corps. Families across South Asia grieved for men lost or wounded at Gallipoli.[15]

Troops from India attended the ceremony at Cape Helles in 1990. Would any of the South Asian governments nowadays wish to commemorate a British Imperial venture? On the other hand, people who have migrated from the sub-continent to Australia might want to be included in the solemnities on Anzac Day.

New Zealanders

‘Anzac’ would not be a word, just a strangled cry, if it were not for the NZ of New Zealand. Australian authors studying the evolution of ‘the Anzac legend’ are scrupulous not to speak for New Zealand. Ken Inglis reminded us that memorials across the Tasman differed from those here. Jenny Macleod has described a very different history for the enshrinement in New Zealand of 25 April as a day of reflection. Many New Zealanders define themselves as not being Australian. The late Duncan Waterson, professor of history at Macquarie University, reported his father’s proudest moment as a New Zealand soldier in the Great War – the defence of a train-load of New Zealand beer against marauding Australians.[16]

Most of the time we Australians complacently ignore the New Zealand presence. When the Anzac Bridge was built a few years back, channelling traffic over an arm of the Harbour into the centre of Sydney, the authorities forgot to install a statue of a New Zealand soldier to face his Australian counterpart at the north-western entry. We Australians bandy about the word ‘Anzac’, resonant as the crack of a stockwhip thanks only to the letters NZ, as if it embodied transcendent qualities found in our Australian nation alone.

New Zealand memorial, Chunuk Bair, Gallipoli (Gallipoli.com.tr)

New Zealand memorial, Chunuk Bair, Gallipoli (Gallipoli.com.tr)

Before 1914, residents of both Dominions looked for work in each other’s country. When war broke out these men might well have gone to the recruitment office in whatever city they happened to live at the time. The man in Australian uniform most decorated on Gallipoli, Captain Alfred Shout, VC, MC, Mentioned in Dispatches, was born and raised in New Zealand. He migrated to Sydney in 1905, already married and the father of a child. He would have been matched by volunteers who had moved in the opposite direction.[17]

New Australians from the Empire

Apart from those who found themselves on the Australian side of the Tasman there was a larger cohort of accidental enlistments in the Australian Imperial Force. EM Andrews has argued that 27 per cent of those in the first contingent of the AIF to go overseas had been born in Britain or Ireland.[18]

In normal times, many of these migrants would have arrived as youngsters with their parents. But the preceding quarter-century had not been normal. Because of a severe depression in the 1890s and a slow recovery, more people left Australia in 1892 and 1893 than entered it, net immigration was very low in the four years following, and was consistently negative from 1898 to 1906 inclusive. Even in 1910, the net gain had only risen to 30 000. Then in 1911 and 1912, the figures jumped to 70 000 and 90 000, higher than any year ever before.[19]

Closer research should reveal how many of the Australian Anzacs were recently arrived young men, desperate to go home to fight. One recently arrived man was John Simpson Kirkpatrick, the Simpson who carried wounded soldiers on a donkey. He came to Australia no earlier than 1910, from Tyneside in the far north of England. He would have spoken with the kind of accent familiar to viewers of the TV series When the Boat Comes In; some Diggers nicknamed him ‘Scotty’. We know from a peace-time letter to his family that Simpson predicted they would see him again in 1915. A later letter said he was on his way home to protect his womenfolk from the Germans massing just across the horizon of the North Sea. From later letters still, we know how angry he was when the troopship dropped its passengers in Egypt rather than taking them all the way to England.[20]

Then there was Lance Corporal Leonard Keysor, who won a Victoria Cross in Australian uniform by catching Ottoman grenades at Lone Pine and lobbing them back before they could explode. A Londoner, Keysor had spent ten years in Canada before he arrived in Sydney in 1913 to visit his sister. The fielding skill that won him the medal would have been the result of practice on English cricket fields, while his bushcraft would have been acquired in Canada. Keysor survived Gallipoli and the Western Front and spent the rest of his life back in London.[21]

Some of these backpacking Anzacs might have stayed in Australia if war had not intervened. At this moment, however, they were young men working their passage around the world, making do among strangers in a strange land. They had taken themselves away from the familiarity and routines and social structures of their homeland. They were adventurers. They exemplified perfectly the stereotype (created by admiring war correspondents) of fit, resourceful and irreverent Anzacs.

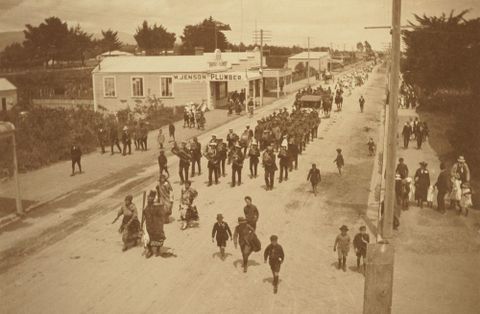

Armistice celebrations, Levin, New Zealand, 13 November 1918 (NZ at War)

Armistice celebrations, Levin, New Zealand, 13 November 1918 (NZ at War)

On the other hand, the locally born among those who sailed from Australia early enough to be at the April landings were, in many cases, already members of the colonial militia. Alfred Shout had been to the Boer War and joined the 29th Infantry Regiment of the Citizens’ Military Force soon after arriving in Sydney. John Monash had been in artillery and infantry corps in Melbourne for almost 30 years.[22]

Members of the militia were likely to answer the call promptly, and we know they were enrolled in preference to the less experienced, especially as the hope lingered that the war might be short if the most suitable people were selected. These men had chosen to spend leisure time in square-bashing and bivouacking. Their experience of rifles had been gained, or honed, by instructors, rather than by shooting rabbits and roos. They understood hierarchy and the uses of discipline. The Australian born who came ashore on 25 April must have been among the most militarily minded men in Australia.

Australian Anzacs did, of course, contrast themselves legitimately with troops in the British Army. British soldiers were long-term employees. British officers represented an entrenched class system, which did not include Jewish engineers such as Colonel Monash, or a carpenter and joiner such as Captain Shout. Australians had volunteered for the militia and they had volunteered for the army. The difference was stark, but less extreme than was conveyed by the adulation, or the dismay, that was expressed by British observers at the time and which grateful Anzac publicists then gold plated. James Brown has lamented in Anzac’s Long Shadow the way that the Digger myth of spectacular amateurism has ill-served both the armed forces and the Australian citizenry’s responsibility for men and women in uniform and after uniform.[23]

It would be interesting to test a possible paradox – that those Anzacs born north of the Equator were the most likely to fulfil the Digger stereotype of innate improvisers. We might imagine larrikin Limeys landing at Anzac Cove in April under and beside Aussies of a marked military bent. We could then at least free ourselves from the complacent simplification of untrammelled Antipodeans outfacing downtrodden Poms.

Changes since 1990: Turkey and Australia

The ceremony at Cape Helles on 25 April 1990 would be a rather different one if it were to be organised today. For one thing, Pakistan would have to stand beside India, and African countries too. President Erdoğan regularly visits countries across the north and west of Africa; he has been to Senegal, for example, in 2013, 2016 and 2018.[24] We and our allies would have to learn – and use – the term ‘Çanakkale’, and may even have to modify our attendance at Anzac Cove. How have things changed?

As the 20th century went on, an amicable relationship developed between Turkey and Australia. For Turkish authorities, the Gallipoli campaign was a striking if costly success, establishing the reputation of Mustafa Kemal as Atatürk, the founder and strong man of a brand new nation. A shared narrative emerged of a gallant encounter between two secular societies, stripped of ideology, and hallowed by a mutual respect of war graves. It helped that substantial tourism to Gallipoli, and a sense of entitlement in Australia, are both fairly recent phenomena.

Turkey and Australia signed a migration agreement in October 1967, allowing for assisted passages for Turkish families. It was in 1971 that Turkish students in a south-western Sydney high school (I think it was Bass Hill) asked if there was a place for them in the school’s Anzac Day ceremony. There was.[25]

Atatürk (centre) and his minister, Şükrü Kaya (right), key players in the saga of the ‘Those heroes’ words

Atatürk (centre) and his minister, Şükrü Kaya (right), key players in the saga of the ‘Those heroes’ words

Such a comforting coexistence was capped in 1985 by setting in stone, at Anzac Cove and outside the War Memorial in Canberra, words attributed to Atatürk. The text ends, ‘your sons are now lying in our bosom and are in peace. After having lost their lives on this land they have become our sons as well.’

David Stephens and Burçin Çakir have shown that we cannot be sure that Atatürk ever uttered or wrote a word of this eulogy, and they have also shown that the most poignant sentence of all – ‘There is no difference between the Johnnies and the Mehmets to us where they lie side by side in this country of ours’ – was the result of ‘embroidery’ by an Australian Gallipoli veteran while he was arranging the translation of the Turkish original. Regardless of this text’s origins, it has worked its magic and has wonderfully strengthened magnanimous sentiment in Australia.[26]

In October 2005, Danna Vale, then Minister for Veterans’ Affairs, proposed an Anzac Cove theme park for the Mornington Peninsula. People who could not travel to the original location would get some sense of its terrain by visiting the coastline of Bass Strait.[27] This was a thought bubble that burst immediately, but it left behind an arresting counterfactual. From the landing at Cape Helles, the invaders had been expected to sweep up the road to Istanbul. If Ottoman forces had stormed the cliffs at Portsea, at the other end of the road to Melbourne, and had been repelled with immense loss of Australian life on three separate occasions without ever reaching Frankston (an analogy with the three Battles of Krithia), how many of us in later generations would have accepted, and how many of us would have deplored and resisted, Turkish claims to sacred custody of Portsea?

The Ottoman and Turkish background

Individual and collective grief is likely to be more immediate in the land where the campaign occurred. The journalist Tony Wright reported a few years ago that fellow passengers on a ferry crossing the Dardanelles sang together the lament for the dead at Gallipoli called Çanakkale, a little as we might all join in Waltzing Matilda.[28]

We have taken for granted the permanence of a secular or ‘laicised’ Turkey, and the implicit ability of the military to intervene whenever there is a challenge to a secular state. That assurance disappeared in July 2016. Part of the army rose against President Erdoğan and was put down by other parts of the army. For a complex of reasons, domestic and regional, a deep undercurrent of religious feeling has reached the surface of Turkish public life.

Until the new Turkish state abolished the rank of ‘Caliph’ in 1924, Istanbul could have been thought of as the de facto capital of the Islamic world. Ottoman sultans had adopted the title of ‘Caliph’, which was first borne by Muhammad’s immediate successors, but now might be loosely translated as ‘Defender of the Faith’, a claim justified by imperial protection of the annual haj or pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina.[29]

Sultan-Caliph Abdülhamid II (Britannica)

Sultan-Caliph Abdülhamid II (Britannica)

In and after 1877, the Ottoman Empire came under sustained attack from Christian powers, from Russia above all, and suffered the secession of Romania, Serbia, Montenegro, the incorporation of territories into the Austrian and Russian empires, Britain’s capture of Cyprus and its strengthened control over Egypt, and the imposition of a protectorate by France over Tunisia.

Sultan-Caliph Abdülhamid II sent out diplomats across the Muslim world, firstly to Afghanistan and India. Religious leaders from Crimea to Kashgar, from the Uzbek lands to Aceh and the Comoro Islands (between Madagascar and Mozambique), responded courteously to him. But they could offer no material support.[30]

It was in July 1908 that a group dubbed the Young Turks, backed by the officers of the Ottoman Third Army in Macedonia, forced the Sultan-Caliph (still Abdülhamid II) to concede parliamentary democracy and a more westernised system of laws.

According to the historian Eugene Rogan, ‘within the military there were clear splits between the officers, who were graduates of the military academies and had liberal reformist leanings, and the ordinary soldiers who placed a higher premium on the loyalty they had pledged to the sultan’. In 1909, soldiers in Istanbul rebelled against their officers and convinced the sultan to abandon the changes conceded the year before. Within a week, the Third Army marched from Macedonia, squashed the counter-revolution, unseated Abdülhamid and replaced him with his younger brother.[31]

When the Ottoman Empire entered the Great War the Young Turks, however, recognised the power of religion. They welcomed the sultan’s pronouncement of a jihad, a call on Muslims everywhere to rally to the Caliph of Istanbul. Domestically, it was intended to unite speakers of Turkish, Arabic and Kurdish behind a profound common cause. Internationally, it was intended to arouse, or at least to immobilise, the huge Muslim populations inside the empires of Britain, Russia and France. The Sultan-Caliph invoked the Koran, the caliphate and the world of Islam. The British invoked ‘God, King and Country’. Chaplains were embedded in the Ottoman forces, just as they were in the armies of the Allies.[32]

The French authorities, it seems, did not trust their ‘Turcos’ to fight wholeheartedly against the guardian of the holy places, so did not send them to Gallipoli. Indeed, some North African Muslims, made prisoners on the Western Front, passed through German detention camps into the Ottoman army. Many of the Senegalese must have been Muslim too, but the French took little heed of that. The Senegalese led the charge on shore at Kum Kale.[33]

The British were also very jittery about pan-Islamism. King George V immediately secured endorsement of the war against Germany from all the Muslim rulers across India. Fear energised and complicated British dealings with the Arabic-speaking world but Great Britain could not do without the Indian Expeditionary Force, a significant proportion of which was Muslim. In October 1914, the Expeditionary Force waited outside Basra for war to be declared, and it fought in Iraq (‘the Mesopotamian Campaign’) until October 1918. Over that time almost 600 000 Indian soldiers engaged Ottoman forces in Iraq. It is not known (yet) if the almost 10 000 Indians on Gallipoli were carefully culled to reduce the complement of Muslim participants there.[34]

The religious turn nowadays in Turkish politics is encouraging substantial reinterpretation of the past. The Çanakkale campaign, the victor’s name for it, is increasingly being presented as a providential and costly rout of unbelievers. The Ottoman language, an amalgam of Arabic, Persian and Turkish, written in a distinctive script, vanished from use with the end of the Empire, so it takes great scholarly and bureaucratic effort to translate Ottoman records and letters. The scrutiny of such material gathers pace. It will inevitably be available for narratives that pre-date – and ignore or confront – the laicised 20th century aftermath of Çanakkale that, it was long thought, had made obsolete the history of what went before.[35]

Pilgrims to Gallipoli from rural Turkey, 2017 (Ayhan Aktar)

Pilgrims to Gallipoli from rural Turkey, 2017 (Ayhan Aktar)

The Islamic State movement has hijacked the word ‘caliphate’. The revival of this concept has drawn out attempts to define and embody it differently. Some prominent Turks have been urging Erdoğan to retrieve Istanbul’s religious primacy.[36] The Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia has alleged, mischievously, that Erdoğan intends to usurp the title of Caliph.[37] That would involve, first of all, Kurdish agreement, a big ask. In recent decades scores of thousands of Uighurs have been welcomed as refugees in Turkey, but the deepening of commercial ties with China, at the other end of the new Silk Road, is transforming the Turkish authorities’ attitude to these fellow Muslims.[38]

On the other hand, after sharing victory in the 2018 Malaysian election in May, Anwar Ibrahim visited Turkey in June, calling Erdoğan’s own election result ‘a victory for the Islamic world in portraying a modern and progressive face of Islam that embraces change while not compromising on the values of our faith and the fundamental teachings of the Holy Prophet’.[39]

As the regime in Turkey struggles to keep its feet in a volatile and contested region, what is undeniable – and irresistible – is the clear-cut triumph against the Western interlopers of the Çanakkale campaign of 1915. As Çanakkale’s reinterpretation evolves, an Australian sense of entitlement will be challenged frontally. Stricter conditions may be applied to access to the battlefields, and applied as well to the decorum expected of visitors. Attendance at the Çanakkale Martyrs’ Memorial may be advisable, may even be required. Yet, once visitors reach the Martyrs’ Memorial, it is a short walk to the French war cemetery at Morto Bay, where 3236 soldiers have their own graves, and it is estimated that the bones of another 12 000 men, unidentified, rest there as well.[40]

Can Australia cope with a fresh perspective on Gallipoli?

Who will tell us of these changing circumstances, and who will help us through them? We Australians are parochial folk. Media coverage of this year’s Commonwealth Games shocked many Australians, and presumably every overseas visitor. Where were the competitors from the other 60 Commonwealth nations? Did only Australians win medals? It was all about Us, Us Australians. For that matter, the commemoration of Anzac has been, for most people, whether popular writers or scholarly writers, mainly about Us.

Help is at hand. But only until the end of the year. On 11 November 2018 we will remember that the Great War ended 100 years ago. It will be a day of global grief and global relief. Will it be remembered that way in Australia? Throughout this year we have been recognising tragedies in 1918 in which Australians participated. Will this clear the decks for Armistice Day, freeing us to recognise that grief engulfed vast numbers of the world’s population? Or will we continue as before?

Anzac Day has become our time of contemplation of all our overseas wars. The Great War brought sorrow to many continents, and to people of many faiths. The Gallipoli campaign was a microcosm of the whole. Australia is now home to people from all continents. Will we be able to carry the global perspective of Armistice Day 2018 over into the Anzac Days of the future?

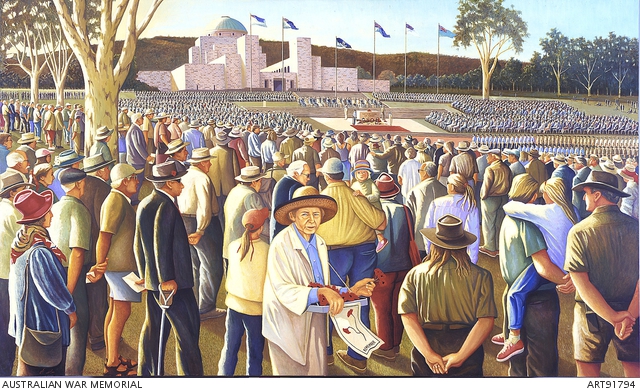

Remembrance Day 2001 (Australian War Memorial/Bob Marchant)

Remembrance Day 2001 (Australian War Memorial/Bob Marchant)

* Barrie Dyster taught Economic History at the University of New South Wales between 1974 and 2014. Sarah Shrubb provided editorial assistance with this article, for which the author and HH are most grateful.

[1] The Age (Melbourne), 26 April 1990; Carolyn Holbrook, Anzac: The Unauthorised Biography (NewSouth, Sydney, 2014), p. 157.

[2] Calculations of the casualties among the Allies on Gallipoli can be found in Robin Prior, Gallipoli: The End of the Myth (UNSW Press, Sydney, 2009), p. 242.

[3] Jeffrey Grey, The War with the Ottoman Empire (Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 2015), pp. 44, 200 (footnote 2).

[4] Accounts of the three Battles of Krithia can be found in Harvey Broadbent, Defending Gallipoli: The Turkish Story (Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2015), ch. 4-6; Prior, pp. 131–55; Tim Travers, Gallipoli: 1915 (Tempus, Stroud, Gloucestershire, 2002).

[5] Geoffrey Moorhouse, Hell’s Foundations: A Social History of the Town of Bury in the Aftermath of Gallipoli (Henry Holt and Co., New York, 1992).

[6] Broadbent, pp. 87–9; Eugene Rogan, The Fall of the Ottomans: The Great War in the Middle East, 1914–1920 (Penguin, London, 2016), pp. 146, 151–2; Travers, pp. 62–3.

[7] Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett, The Uncensored Dardanelles (Hutchinson, London, 1928), p. 86.

[8] Moorhouse.

[9] Jeff Kildea, Anzacs and Ireland (UNSW Press, Sydney, 2007), pp. 15, 18, ch. 2.

[10] Ashmead-Bartlett, p. 86; Anthony Clayton, The Wars of French Decolonisation (Longman, London, 1994), p. 4; Leonard V. Smith, Stephane Audion-Rouzeau & Annette Becker, France and the Great War, 1914–1918 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2003).

[11] John Horne, ‘Why we don’t hear about the 10,000 French deaths at Gallipoli’, The Conversation, 24 April 2015, https://theconversation.com/why-we-dont-hear-about-the-10-000-french-deaths-at-gallipoli-40014 , viewed 16 September 2018.

[12] Robert Aldrich, Greater France: A History of French Overseas Expansion (St Martin’s Press, New York, 1996); Harvey Broadbent, Gallipoli: The Fatal Shore (Viking Penguin, Melbourne, 2005), pp. 84–5, 119–20; Myron Echenberg, Colonial Conscripts: The Tirailleurs Senegelais in French West Africa, 1857–1960 (Heinemann, London, 1990).

[13] ‘Welcome to the International Organisation of the Francophonie official website’, https://www.francophonie.org/ , viewed 3 July 2018.

[14] ‘Foreign embassies and consulates in Australia’, https://protocol.dfat.gov.au/Public/MissionsInAustralia , viewed 3 July 2018.

[15] Broadbent, Gallipoli, pp. 49, 64, 95–6, 114, 136; Cecil Malthus, Anzac: A Retrospect (Whitcombe & Tombs, Christchurch, 1965), p. 47; Phil Taylor & Pam Cupper, Gallipoli: A Battlefields Guide (Kangaroo Press, Sydney, 2nd edn, 2000), p. 159; Travers, p. 270.

[16] KS Inglis, Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape (MUP, Melbourne, fully updated 3rd edn 2008); Jenny Macleod, Gallipoli (OUP Press, Oxford, 2015).

[17] Broadbent, Gallipoli, p. 198; RSL Virtual War Memorial, ‘Alfred Shout’, https://rslvirtualwarmemorial.org.au/explore/people , viewed 3 July 2018.

[18] EM Andrews, The Anzac Illusion: Anglo-Australian Relations during World War One (CUP, Melbourne, 1993), p. 44.

[19] Barrie Dyster & David Meredith, Australia in the Global Economy: Continuity and Change (CUP, Melbourne, 2012), figure 3.1, p. 59; Charles Price, ‘Immigration and ethnic origin’, Wray Vamplew (ed.), Australians: Historical Statistics (Fairfax Syme & Weldon Associates, Sydney, 1987), pp. 6, 8, 12.

[20] Peter Cochrane, Simpson and the Donkey: The Making of a Legend (MUP, Melbourne, 1992).

[21] Mark Dapin, Jewish Anzacs: Jews in the Australian Military (NewSouth, Sydney, 2017); RSL Virtual War Memorial, ‘Leonard Keysor’.

[22] RSL Virtual War Memorial, ‘John Monash’, ‘Alfred Shout’.

[23] James Brown, Anzac’s Long Shadow: The Cost of Our National Obsession (Redback, Melbourne, 2014).

[24] ‘Erdoğan’s Senegal visit to promote Turkey’s Africa policy’, Daily Sabah, 28 February 2018,

, viewed 25 July 2018.

[25] ‘Turkish migration to Australia’, Australian Embassy, Ankara, https://turkey.embassy.gov.au/anka/TurkMigration.html , viewed 3 July 2018; dinner table conversation, winter 1971.

[26] David Stephens & Burçin Çakir, ‘Myth and history: the persistent Atatürk words’, David Stephens & Alison Broinowski (ed.), The Honest History Book (NewSouth, Sydney, 2017), pp. 92–105.

[27] Mike Seccombe, ‘It’s a long way to Gallipoli – so create one here’, Sydney Morning Herald, 18 October 2005.

[28] Tony Wright, Turn Right at Istanbul: A Walk on the Gallipoli Peninsula (Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2003), p. 46.

[29] Hugh Kennedy, Caliphate: The History of an Idea (Basic Books, New York, 2016); Donald Quataert, The Ottoman Empire, 1700–1922 (CUP, Cambridge, 2000), pp. 81–3, 166, ch. 6.

[30] Pankaj Mishra, From the Ruins of Empire: The Revolt against the West and the Remaking of Asia (Allen Lane-Penguin, London, 2012), pp. 69, 88–97; Quataert, pp. 76–83; Rogan, The Fall of the Ottomans, pp. 2–7; Wilfred Cantwell Smith, Islam in Modern History (New American Library, New York, 1957), pp. 88–9, 190–1.

[31] Rogan, pp. 8–9.

[32] Broadbent, Defending Gallipoli, pp. 1–2; Rogan, p. 48.

[33] Horne; Rogan, pp. 65, 71-74, 151–2, 270–1, 396–7.

[34] David Omissi (ed.), Indian Voices of the Great War: Soldiers’ Letters, 1914–1918 (Palgrave Macmillan, London, 1999); Rogan, pp. 70–1, 243–4, 249–50.

[35] Quataert, pp. 192–8.

[36] Adam Taylor, ‘“The caliph is coming, get ready”, pro-Erdoğan politician tweets’, Washington Post, 19 March 2015.

[37] ‘Saudi Crown Prince outs “triangle of evil”’, https://www.news.com.au/world/middle-east/saudi-crown-prince-outs-triangle-of-evil/news-story/c0a722a2f46f90175fb2fe46b33e0446 , 8 March 2018.

[38] Giorgio Cafiero & Bertrand Viala, ‘China–Turkey relations grow despite differences over Uighurs’, Middle East Institute, 15 March 2017, https://www.mei.edu/content/article/china-turkey-relations-grow-despite-differences-over-uighurs , viewed 3 July 2018; Philip Wen, ‘Erdoğan out to avoid dispute’, Sydney Morning Herald, 30 July 2015.

[39] Quoted in Amanda Hodge, ‘Anwar defends praise for Turk strongman’, The Australian, 30 June 2018.

[40] ‘The French War Cemetery and Çanakkale Martyrs Memorial’, https://anzacportal.dva.gov.au/history/conflicts/gallipoli-and-anzacs/locations , viewed 3 July 2018.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.