‘Rewriting the history of Gallipoli: a Turkish perspective’, Honest History, 25 July 2017 updated

[This piece draws upon my article originally published in the Turkish daily newspaper Taraf (Istanbul), 18 March 2014. An earlier English translation by Hikmet Pala was uploaded to my Academia page. Secondly, the article adapts material later published in English as chapter 9 of Australia and the Great War: Identity, Memory and Mythology (2016), edited by Michael JK Walsh and Andrekos Varnava. The chapter was called ‘Mustafa Kemal at Gallipoli: The making of a saga, 1921-1932’. (Update 23 August 2017: the article is now available on Academia.) Thirdly, the article takes account of recent developments in Turkey, as noted in my joint piece with Brad West, in The Conversation in April 2017, and on the Honest History site. Finally, I would like to thank David Stephens for his careful reading, suggestions and editorial help in the final version of this paper.]

***

The history of the Gallipoli campaign has been contested in Turkey for many decades. The commemorations of the Ottoman naval victory of 18 March point to Staff Lieutenant Colonel Mustafa Kemal (later Atatürk) as ‘the only man, the only commanding officer’. Yet, this official narrative contradicts Atatürk’s own almost contemporary version, where his role was minimal on that day.

On the other hand, Mustafa Kemal later tried, for political and career reasons, to highlight his role in the land operations commencing 25 April. While he was fairly unsuccessful in his efforts to appoint himself to a decision-making position within the Young Turk regime, historians on the Allied side (Bean, Churchill and General Aspinall-Oglander), turned him into ‘the Man of Destiny’. The myth grew in the turbulent international relations of the early 1930s and has been consolidated since.

Parallel, however, to the glorification of Mustafa Kemal have been shifting narratives of the Gallipoli campaign as the army of Muslims defending the House of Islam against the Crusaders, the men wearing crosses. There is evidence that this Islamist narrative is growing in importance in today’s Turkey. Finally, in the background of Gallipoli commemorations there has always been the elephant in the room, that is, the Armenian Genocide. This event commenced on 24 April 1915 and its place in Turkish history is still debated.

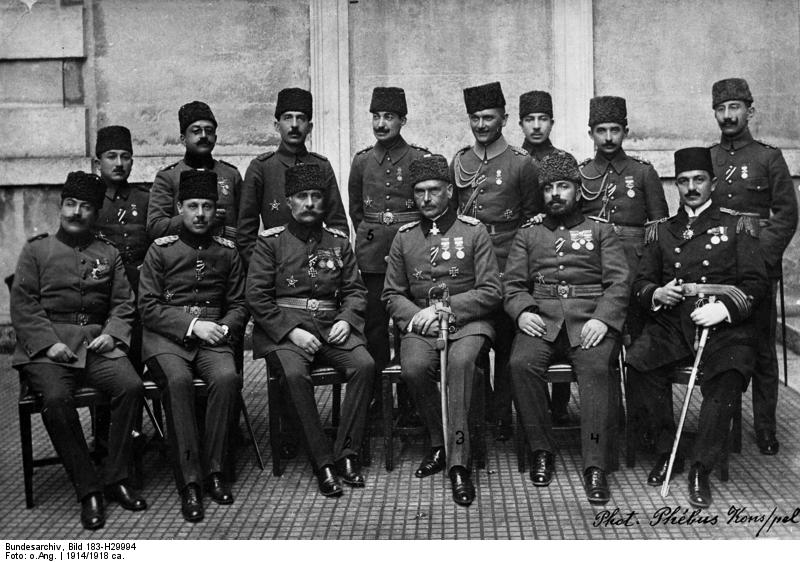

Senior Turkish and German officers, January 1916, after the Gallipoli campaign. Mustafa Kemal is not present. (Bundesarchiv)

Senior Turkish and German officers, January 1916, after the Gallipoli campaign. Mustafa Kemal is not present. (Bundesarchiv)

From right to left standing: Abdi Bey (?); Lt. Colonel İsmet (Ministry of War, Operations Section, later adopted surname İnönü, second president of Turkey after Atatürk); Aide First Lt. Asım (Gündüz); Aide of Liman von Sanders, Major Erich Prigge; Chief of Staff to 5th Army, Lt. Colonel Kazım (İnanç); Chief of Staff to 1st Army, Lt. Colonel Şükrü Naili (Gökberk); 2nd Army Chief Medical Officer, Colonel Dr. Refik Münir (Keskindil) Bey; 1st Army Chief Medical Officer, Lt. Colonel Dr. İbrahim Talî (Öngören).

From right to left sitting: Ministry of Navy, Chief Staff Officer, Navy Commander Hüseyin Rauf (Orbay); CO of the Southern Sector at Gallipoli, Brigadier Gen. Mehmet Vehip (Kaçi); Commander of the 5th Army, Field Marshal Liman von Sanders; CO of the Northern Sector at Gallipoli, Major General Esat (Bülkat); Ministry of War, Chief Medical Officer, Brigadier General Dr. Süleyman Numan; CO of Istanbul Military Garrison, Colonel Cevat.

Commemorating the naval victory of 18 March 1915

I vividly recall a night in 2014, the 99th anniversary of the naval victory of 18 March at the Dardanelles. We anticipated that we would be subjected, through the mouths of statesmen, to the bombast of heroism on various TV channels. As the top politicians spoke in their stately manner, black and white pictures would be displayed, culminating with Kemal Atatürk emerging like a sun in the background. The official line about Atatürk’s military genius and bravado would be repeated, presenting him as the saviour of the country, winning us the battles of Gallipoli …

On 18 March 1915, the allied British and French fleets launched an attack to pass through the straits of the Dardanelles. Ottoman artillery units and navy attempted to prevent this through batteries of heavy artillery and howitzers strategically located on both sides of the straits and with the aid of eleven lines of sea mines. These dispositions achieved their goal and the naval defence of Gallipoli was one of the most significant victories of the Ottoman side throughout World War I.

At that time, the 19th Infantry Regiment under the command of then Staff Lieutenant Colonel Mustafa Kemal (later Atatürk) was based in Maydos (later renamed as Eceabad). In 1916, when then General Mustafa Kemal was appointed to the Eastern Front, the History of War Commission in Istanbul commissioned him to write a report on the Arıburnu battles. He told the story of 18 March in the introduction of his report:

On that day, Cevat Pasha, the commander of the Fortified Zone [at the Dardanelles], requested my presence and asked to see me at Kilitbahir [Fortress on the European side]. Following my arrival and meeting him, again he asked me to accompany him – along with the Inspector-General of the Shores and Straits Admiral [Guido von] Usedom – to visit coastal artilleries and fortifications on the European shore [of the Dardanelles] and to choose convenient locations to position additional mobile batteries. We obliged. We accompanied Cevat Pasha, the commander of the Fortified Zone, and proceeded to Kirte, [Krithia, an evacuated Greek village on the southern side of the Gallipoli peninsula]. Upon reaching our destination … we observed that the enemy navy approached to the entrance of the straits, targeting their bombardment to Kirte and Alcitepe [Achi Baba], where we were caught under fire. To enable Cevat Pasha to return back to his GHQ [on the Asian side of the Dardanelles], we reverted to Maydos. The battle of that day took place solely on the sea, ending up with the defeat of the enemy forces. Other than some enemy battleships bombarding the shores, no notable engagement on land happened.[1]

Tour buses, Gallipoli, April 2017 (author). The sign says, ‘Martyr! We are following your example.’

Tour buses, Gallipoli, April 2017 (author). The sign says, ‘Martyr! We are following your example.’

The forgotten heroes of 18 March

So, Mustafa Kemal’s narrative of 18 March shows that he was merely watching the enemy attack and the artillery defence through his binoculars. If we need to look for ‘heroes’ for 18 March, we are better off looking at Cevat (later Çobanlı) Pasha, the commander of the Fortified Zone at Dardanelles, and German Admiral Guido von Usedom, who was entrusted by Enver Pasha, the Minister of War, with the special mission of defending the Straits, that is, the Dardanelles and the Bosphorus (Istanbul). In fact, these two men prepared the plans, laid the mines, commanded the forces, and defended the Dardanelles on 18 March 1915.

The narrative of Mustafa Kemal simply indicates that Cevat Pasha was on the European side of the straits on that day and reached his headquarters on the Anatolian side in the afternoon. In the absence of Cevat Pasha all coastal artillery units were commanded by Staff Lieutenant Colonel Selahattin Adil. He was the Chief of Staff of the Fortified Zone Command. He handed over the command to Cevat Pasha at 14:00 hours. Yet, do we ever mention the name of Selahattin Adil during our 18 March commemorations?

We also hear a lot on these occasions about the legendary minelayer Nusret. Yes, the Nusret did lay mines parallel to the shore at the Bay of Erenköy in the morning of 8 March, causing catastrophic damage to the enemy fleet ten days later. Thanks to these mines, the enemy battleships Irresistible and Ocean were sunk and three more battleships were put out of action. Recently, it was established also that the Bouvet sank due to artillery fire coming from Ottoman coastal artillery.[2] Rightly, we hear about Captain Hakki of Tophane, the captain of the Nusret, and Major Hafiz Nazmi, the commanding officer of the Mine Group Command in the navy. But no one mentions the critical roles played by German military personnel on the Nusret that day, such as the mine specialist Lieutenant Colonel Geehl, the torpedo specialist Senior NCO Rudolf Bettaque, and the navy engineer Captain Reeder, who managed to run the Nusret’s engines without releasing dark smoke through her funnel. This made it less visible to enemy reconnaissance.

German officers at Gallipoli

Tombstone of Lieutenant Hans Woermann, German Military Cemetery, Tarabya, Istanbul (author)

Tombstone of Lieutenant Hans Woermann, German Military Cemetery, Tarabya, Istanbul (author)

Leaving aside the Ottoman officers who contributed to the victory but who are not mentioned, our Turkish ‘national history’ deems the German officers non-existent. On 18 March, while there were 79 dead and wounded among Ottoman forces, the loss in the German camp was 18 soldiers. So, for every four Ottoman losses, there was one German loss too. In the same fashion, the loss of German artillery Lieutenant Hans Woermann is glossed over. In his memoirs, Colonel Hans Kannengiesser, the commander of the 16th Army Corps at the Suvla battles in August 1915, describes the funeral of Lieutenant Hans Woermann, as follows: ‘As befitting an officer of the Turco-German Alliance, the Salâ[3] was recited from the mosque’s minaret [in Çanakkale] and, his body wrapped under the Turkish flag, his face was turned by a Hodja towards Mecca as he was buried’.[4] Ottoman officers did not hesitate to show their respect to the comrades-in-arms who died in defence of the Ottoman fatherland. Dismissing the dead of their allies and ‘crying only after their own dead’ is a skill unfortunately developed by the historians of the Turkish Republic!

Turkish myths are highlighted, however. Whenever the naval battle of Gallipoli is told, the story of Corporal Seyit is recounted. There are outrageous claims made, almost as if the entire Allied navy was stopped by this Corporal Seyit, who is said to have carried a heavy shell on his back and rammed it into the muzzle. In this way, the history of a modern battle is being reduced to a legend, in fact, turning the whole victory into a laughing stock.

Corporal Seyit carrying a wooden replica of the famous shell (Wikipedia)

Corporal Seyit carrying a wooden replica of the famous shell (Wikipedia)

It is unfortunate that the stories have not also been recorded of the German soldiers who fought within the Ottoman army during the Gallipoli campaign. Near the beginning of World War I the number of German staff and military personnel was around 1100, but towards the end of 1918 this figure reached 18 000 to 20 000. Although initially the memoirs of a few officers were published, including those of Field Marshal Liman von Sanders, the commanding officer of the 5th Army, the notorious bombardment of Potsdam in 1945 destroyed the German military archives and prevented comprehensive academic research being done on this topic. The archives of the Turkish Chief of Staff in Ankara have a large collection of German documents on World War I, but they are not available to readers. Perhaps, when the military control on history writing is lifted in the year 2065 (!), researchers will gain access to these documents.

‘Turkification’

Since the 1930s, there have been a few turning points in rewriting the history of the Gallipoli campaign. At first, the victory of the good old Ottoman Imperial Army was ‘Turkified’, and Arab, Armenian, Greek, Jewish and Kurdish soldiers and officers were cleansed from the official history. There was a conscious effort to impose the idea that all the participating soldiers and officers of the Gallipoli campaign were ‘pure ethnic Turks’.

So, the cosmopolitan character of the Ottoman army – essentially a multi-ethnic and multi-religious Imperial army – was intentionally ignored. As ‘Turks’ were said to have comprised the entire army, German officers were also treated as a type of undesirable persons. They had no place in our glorious Turkish history! Also, the narratives of the 1930s were reconstructed in such a way as to make the Gallipoli campaign a precursor of – almost a period of preparation for – the Turkish War of Independence: the presence of Mustafa Kemal on the Gallipoli Peninsula was used to connect the Gallipoli campaign of 1915 to the War of Independence that started in May 1919.

Pilgrims, Gallipoli, April 2017 (author)

Pilgrims, Gallipoli, April 2017 (author)

The glorification of Mustafa Kemal 1915-32[5]

Although Mustafa Kemal did not become Atatürk (‘father Turk’) until late 1934, his glorification began well before that. The saga of Mustafa Kemal at Gallipoli was first shaped abroad and then imported into Turkey. Contrary to the general understanding that exists today, Mustafa Kemal was not known to the Ottoman public during the war and his name was mentioned only once in the Ottoman press at that time. After the Gallipoli campaign, Mustafa Kemal tried, fairly unsuccessfully, to use his career at Gallipoli to advance his political ambitions. He had begun to develop an image of himself as the saviour of the nation, particularly compared with men whom he thought of as his domestic rivals, such as Enver Pasha, the Minister of War, as well as the German military command in Istanbul.

Mustafa Kemal was not mentioned at all in two important post-Gallipoli ceremonies in Istanbul and his further self-promotion efforts were mostly blocked by Enver Pasha. Mustafa Kemal wrote two short accounts of the Gallipoli campaign, a prosaic treatment in 1916 of April-July 1915 (referred to previously in this article), then, in 1918, a more boastful write-up of the events of August 1915, although the latter remained unpublished during his lifetime.

Paradoxically, it is on the Allied side where Mustafa Kemal features more noticeably and, even then, this does not occur straight away. Mustafa Kemal first appeared in Anzac military intelligence reports on 26 or 27 April 1915, when an Ottoman Armenian POW captured in the first days of the war named him as the commander of the 19th Division. Apart from this entry, he does not feature much in British or Anzac intelligence reports.

Pilgrims, Gallipoli, 2017 (author)

Pilgrims, Gallipoli, 2017 (author)

Andrew Ryan, a senior political officer at the British High Commission in Istanbul immediately after the war, recalled in his memoirs (published in 1951) that in April 1919 Mustafa Kemal’s name had conveyed nothing to him. In 1919 also, a group of British officers (the Mitchell Committee) visiting Istanbul and Gallipoli interviewed many high level Ottoman officers about the wartime operations on the Ottoman side of the trenches. Mustafa Kemal’s name only came up twice in the Mitchell report, both times misspelt.

By this time, around May 1919, Mustafa Kemal had moved to Anatolia to organise the Turkish national resistance against the invading Greek army. After the victory against the Greek forces and the fall of Izmir in September 1922, he no longer needed a reputation from the Dardanelles. He had become a national hero, indeed saviour of his country and the founding father of the Turkish republic in 1923.

The losing side at Gallipoli was not finished with Mustafa Kemal, however. The Australian and British histories of the Gallipoli campaign began to shape his legend. Charles Bean, war correspondent at Gallipoli and now the Australian official historian, played a special role. He argued that Mustafa Kemal’s actions had been vital to Ottoman success. This respect for the enemy and its commander probably made the Anzac defeat more honourable. As British historian Jenny Macleod puts it, Bean could justify the loss only by dignifying the enemy: ‘perhaps to fail against an admirable leader and admirable race is palatable’.[6]

Bean had visited Gallipoli even before the Mitchell Committee, spoken to Ottoman Major Zeki from the legendary 57th Regiment, and heard from him of Mustafa Kemal’s role on 25-27 April. The Australian boosting of Mustafa Kemal proceeded from that point, commencing with the publication in 1921 of the first volume of the Official History, where Bean referred to Kemal’s ‘swift determination’ and ‘a formidable force under a formidable leader’.

Then came Winston Churchill. He had been bruised by Gallipoli as First Lord of the Admiralty and investigated by his peers in the Dardanelles Commission. He was anxious to refashion history in his own favour. He coined the term ‘Man of Destiny’ for Mustafa Kemal and – in volume 2 of The World Crisis 1911-1918 – gave him a central role in the events of April and August 1915. In order to explain the defeat at these critical moments, Churchill tried to rationalise the defeat by glorifying the enemy. And in 1923, the very year Churchill’s account was published, Mustafa Kemal became President of the new Turkish republic, destined to be a key player in Balkans and Near East politics, in which Britain had a close interest. Churchill may have been looking forward as well as back.

Churchill was not an official historian, though he was intent on justifying his actions in government. The British official history was slow to get under way but began to make progress under General CF Aspinall-Oglander early in 1925, when Bean and Churchill’s accounts had already been published. Aspinall-Oglander’s account of Mustafa Kemal at Gallipoli looked very much like Churchill’s. It was to be included in the second volume of the official history, due for publication in 1932, but there was to be some diplomatic messaging first.

Relations between Britain and Turkey at this time were not good. Official British records show that the Foreign Office in the autumn months of 1931 put polite pressure on Aspinall-Oglander to make his treatment of Mustafa Kemal even more laudatory. The ‘doctored’ words were duly included in the final version of the volume and a specially bound copy was presented to Mustafa Kemal in May 1932. With British support, Turkey entered the League of Nations a little later.

Sir George Clerk, British Ambassador in Ankara, who in May 1932 presented President Mustafa Kemal with his specially bound volume of the ‘doctored’ official history (Wikipedia)

Sir George Clerk, British Ambassador in Ankara, who in May 1932 presented President Mustafa Kemal with his specially bound volume of the ‘doctored’ official history (Wikipedia)

Mustafa Kemal would have particularly liked this (post-Foreign Office intervention) paragraph in the epilogue of the volume:

Seldom in history can the exertions of a single divisional commander have exercised, on three separate occasions, so profound an influence not only on the course of a battle, but perhaps on the fate of a campaign and even the destiny of a nation.

So, the legend of Mustafa Kemal at Gallipoli was shaped in Sydney and London first and imported into Turkey later. It found a wide market there and continued to shape Turkish official historiography until at least 2014. But has this begun to change?

‘Islamisation’

In the years immediately after 1915, pro-Islamists such as Mehmet Akif Ersoy – the lyrics of the Turkish National Anthem came from him – wrote poems and articles presenting the Gallipoli campaign as a kind of ‘resistance of Islam against the Infidel’. However, in the official narrative of national history, the Gallipoli campaign was never treated as an ‘invasion of Crusaders into the House of Islam’.

In recent years, though, perhaps since the mid-1990s, the municipal mayors elected from Islamist political parties, hiring coaches and taking residents and school children to tours to Gallipoli, have brought a new twist to the writing and presentation of history, and started disseminating for these groups a concept of ‘the Islamic army resisting the Infidel’, as opposed to the former narrative of ‘the Glorious Turkish Army’ (which is the version that secular-nationalist groups still receive).

Now, for these Islamist people, tours to the Gallipoli peninsula, the war memorials and graves are being treated as a kind of ‘pilgrimage’. As Brad West and I noted recently, approximately one million Turks every year visit Gallipoli, and around ten per cent of the Turkish population has been on some kind of ‘martyr tourism’ trip to Gallipoli.[7]

The Gallipoli campaign [we said] has, in recent years, become part of the culture wars in Turkey associated with the rise of political Islam. This has seen Gallipoli increasingly referred to in relation to an Islamic jihad, and as an invasion of crusaders into the house of Islam.[8]

During the spiritually oriented tours, we see a newly invented epic war saga befitting the stories of ‘The Battles of His Grace Ali’.[9] For example, the 38 centimetre diameter projectiles fired from HMS Queen Elizabeth to the Turkish trenches were said to have been seized in the air by the Islamic saints who were supposed to be patrolling constantly over the peninsula. Or a white cloud comes down from the blue sky and a British regiment vanishes mysteriously.[10] Islamic mythology has no limits.

Since 2012, the ruling AKP’s Istanbul party headquarters has organised an annual ‘Breaking the Fast Day’ program comprising ‘the Menu of the Martyrs’ at the Gallipoli Martyrs’ Memorial in the Holy Month of Ramadan. By launching this program, a deliberate attempt is being made to increase ‘Islamic sensitivity’ in relation to the Gallipoli campaign. The program consists of thousands of attendees breaking the Ramadan daytime fasting period with rye bread, cracked wheat soup and water, followed by reciting the Qur’an, and poems of a nationalistic and inflated heroic nature.

End of Fasting Day, Martyrs Memorial, 2015 (supplied)

End of Fasting Day, Martyrs Memorial, 2015 (supplied)

One of the indispensable parts of Turkish nationalistic and conservative politics is the attempt to portray Turks as the ‘downtrodden’, victimised masses, suffering from ‘poverty and deprivation’. The average Turkish nationalist would always belittle himself and his people in order to increase the dose of victimisation. In fact, the logic of it is very simple: if the soldiers of 1915 had not been fed properly, they would have lost the war! Lieutenant Colonel Cemil Conk, the commander of the 4th Infantry Division on the Gallipoli Front, wrote this in his memoirs on the feeding and provisions regime for soldiers:

Each private was issued with 900 grams of bread daily. The hot meals consisted of chicken soup, meat and bean stew, meat and chickpea stew, cracked wheat pilaf, dry broad beans and dried fruit compote. For snacks, they were issued dried sultanas and roasted hazelnuts. There was a regular distribution of tobacco as well.

This is the historical truth from contemporary evidence; it is unfortunate that it does not comply with the ideological blueprints of the nationalists of all types.

In recent years, the number of people regarding the Ottoman Gallipoli campaign as a ‘Jihad’ – a resistance to the Crusaders, the Crescent versus the Cross – has been on the increase. For instance, then Prime Minister Erdoğan said in 2013:

No one should try to say that “the Crusades were this and that!” ever again. The Crusades were not [finished] nine centuries in the past! Do not forget, the Gallipoli [campaign by the Allies] was a Crusade. Who was [fighting] alongside us [against the Crusaders] is obvious. At that time, individuals from Syria were with us. There were [soldiers] coming from Egypt, who fought with us. There were those from Bosnia, Kosovo, from all of the Balkans![11]

At this point one should recall some facts. If World War I was a war among so-called imperialist powers to reshape their zones of influence, the allies of the Ottomans were the ‘Imperialist’ Germans, Austrians-Hungarians and the Bulgarians. (By the way, all of them were Christians!) The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), the then Ottoman government, had gambled the future of the Empire on signing a secret deal with Germany on 2 August 1914. The following day, Enver Pasha, Minister of War, declared a general mobilisation. On 29 October 1914, the Ottoman navy began the shooting war by opening fire on the Russian fleet, bombarding Russian ports in the Black Sea. Here, the Ottoman state was not the aggrieved and downtrodden party, but clearly the belligerent force, the party which actually started the war.

The famous 5th Army that defended the Gallipoli Front was commanded by a German, Field Marshal Liman von Sanders. The Chief of Staff of the Ottoman Imperial Army was the German General Fritz Bronsart von Schellendorf. In 1914, moreover, the present independent Arab states of Syria and Iraq were merely Ottoman provinces. Those men conscripted to the Ottoman army were born as Ottoman citizens anyway. They were not in a position to come onto the Ottoman side voluntarily; they were merely complying with their compulsory military service. It is a fallacy to liken this war to an Islamist Jihad, when it was fought with German money, German military aid, and the active participation of the German military command, in combination with the devious and finely tuned plans of the CUP leadership.

One could argue that the Ottoman Sultan Mehmet V and the CUP government did actually declare Jihad on 14 November 1914 after the declaration of war on the Entente powers. Yes, this is true! But what distinguished the 1914 Jihad from the previous ones in the 18th century was not the terms of its declaration, but the selective focus of its targets – that is, including Entente civilians, along with armies – and the pointed exemptions for German and Austro-Hungarian nationals. This was a parody of the idea of Jihad, and one for which there was no known precedent in the Islamic world. In essence, this was a declaration of Jihad to satisfy the German Foreign Ministry.[12]

Oddly enough, the Germans believed in the declaration more than the Ottomans did. This is not surprising, when we recall that the impetus behind the declaration did not come from Ottoman religious dignitaries but rather from German diplomats. The best comment on the 1914 Jihad came from the overthrown Sultan Abdülhamid II, who was still alive and confined in one of the palaces on the Bosphorus. As he said to his daughter, Ayşe Osmanoğlu,

not Jihad itself but its name was a weapon in our hands. [In my time] whenever I wanted to intimidate one of the Ambassadors [in Istanbul], I would say “a Muslim Caliph has a word in his mouth [to be used in the last instance], I pray to Allah not to [be forced to] pronounce it. For us, Jihad was just a name. Because of not having a substance, it did not have any [executive] power either. How could [the CUP] get over it? Will the British be deceived by this [declaration of Jihad]? [13]

No doubt, the old fox knew the possibilities far better than did the ‘arriviste’ Young Turks.

Still, it is the status of Atatürk that is of particular interest. As noted above, his profile in and around Gallipoli has been toned down relative to the Islamist narrative. On the ground, there has been the recent uncertainty over the Turkish memorials, which are being renovated. It is understandable that the Australian interest has centred on the future of the 1985 Atatürk memorial at Anzac Cove, which carries words attributed to Atatürk himself. The Gallipoli Battlefields Historical Park Authority (Çanakkale Savaşları Gelibolu Tarihi Alan Başkanlığı) has officially declared that the inscription will be restored to this memorial just as it was before. However, the renovation has still raised some questions in secularist nationalist circles in Turkey, as well as abroad.[14]

Pilgrims, Gallipoli, April 2017 (author). The t-shirts say, ‘Grandpa, I came’.

Pilgrims, Gallipoli, April 2017 (author). The t-shirts say, ‘Grandpa, I came’.

The unresolved problem: dealing with the Armenian Genocide

In 2014, when I was writing the earlier version of this article, it was easy to figure out that the 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide would be burdensome for the Turkish political elite. I anticipated that a policy of ‘alleviation of mutual suffering’ would be adopted in 2015 to resist the international pressure regarding the Armenian issue. As early as 25 April 2011, then Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu spelled out the state policy:

On his arrival at Gallipoli, Minister Davutoğlu said: “Any Turk [in this place] whose heartbeat does not jump a notch, his heart tremble, the flow of blood in his veins quicken, cannot be a Turk … We will present the year 2015 to the entire world, not as the anniversary of an alleged genocide slander, but as the anniversary of the glorious resistance of a nation, the anniversary of Gallipoli defence.”[15]

So, the intention was obvious: to respond to the victimisation of the Ottoman Armenians, something that aroused pity, by balancing the sympathy: ‘Yeah, but we Turks died at Gallipoli, too’. Thus, attempts would be made to neutralise the pressure abroad and justify the causes of the Armenian massacres within the country.

Designed by the statesmen in Ankara, this narrative was readily adopted by nationalist Turkish historians. For instance, Professor Metin Hülagü, then President of the Turkish Historical Society, instantly adopted the state line and argued the following:

When mentioning 2015, people should keep Gallipoli in their minds and not the Armenian problem. If the Gallipoli Campaign did not take place, if the French and the British did not land at Gallipoli, the Armenian question would not have happened! France and Britain coming here from thousands of kilometres away, attempting to invade Anatolia, reaching the Dardanelles, then taking the Russians and Armenians on their side, then turning around and asking: “Why did you forcibly relocate them?” If they had not come, neither a war in Anatolia nor the relocation [of Armenians to the Syrian deserts] would have occurred. If the Armenians want to hold someone accountable, they should put their questions to the French, the British, and the Russians. Why are they questioning us?[16]

Unfortunately, this was exactly how the centenary of Gallipoli commemorations turned out in April 2015.[17] The main Turkish commemoration of 25 April, with international dignitaries present, was held a day before on 24 April, the centenary of the beginning of the Armenian deportations, overshadowing that event. In the two years and more since then, adopting Erich Maria Remarque’s title, it has been ‘All quiet on the Turkish Front’.

Pilgrims (in commemorative t-shirts) at prayer, Gallipoli, April 2017 (author)

Pilgrims (in commemorative t-shirts) at prayer, Gallipoli, April 2017 (author)

Conclusion

I have shown how Islamisation is taking over from Turkification in the remembrance of Gallipoli. Time will tell how this trend develops. Against this background, we can also speculate about the future of the Atatürk myth and legacy. Atatürk has been the central figure in Turkish history for almost a century. Yet his role in the Gallipoli campaign was glorified after the event, largely through the efforts of the historians of his former enemies; his fame was boosted in the 1930s for diplomatic reasons – as it has been reaffirmed since the 1980s, as David Stephens and Burçin Çakır have shown recently.[18]

Now, Atatürk seems to be on the wane again, as Islamist narratives become more important in Turkish politics. Meanwhile, regardless of which narratives – secular nationalist or Islamist – prevail, the much bigger 1915 story, the sad fate of the Ottoman Armenians, remains as an unreconciled piece of Turkish – and world – history.

* Ayhan Aktar, Institute of Social Sciences, Istanbul Bilgi University, Turkey, is a National Library of Australia Fellow during 2017.

Notes

[2] See: Ayhan Aktar, ‘Who sank the battleship Bouvet on 18 March 1915? Problems of imported historiography in Turkey’, War and Society, forthcoming, August 2017.

[3] Salâ’, Salât: call for the funeral prayer.

[4] Lieutenant Hans Woermann was later re-buried in the German Military Cemetery in Tarabya, Istanbul.

[5] The following paragraphs are based on my chapter in the Walsh and Varnava collection, Australia and the Great War: Identity, Memory and Mythology, with the permission of the editors, who hold copyright; full references are there.

[6] Jenny Macleod, Reconsidering Gallipoli, Manchester University Press, Manchester, 2004, p. 78.

[7] Brad West & Ayhan Aktar, ‘How a more divided Turkey could change the way we think about Gallipoli’, The Conversation, 21 April 2017, https://theconversation.com/how-a-more-divided-turkey-could-change-the-way-we-think-about-gallipoli-74252, viewed 11 July 2017.

[8] West & Aktar. For an early Australian report of this phenomenon: Ruth Pollard, ‘Islamic rewrite of Gallipoli legend’, Sydney Morning Herald, 25 April 2013, https://www.smh.com.au/national/islamic-rewrite-of-gallipoli-legend-20130424-2if2m.html, viewed 11 July 2017.

[9] Hazret-i Ali, His Grace/Saint Ali: son-in-law of the Prophet Mohammed, known for his prowess as a warrior.

[10] For an excellent treatment of this myth, see Ian McGibbon, ‘A day to remember: the missing regiment’, NZ Skeptics, no. 52, 1 August 1999, https://skeptics.nz/journal/issues/52/a-day-to-remember-the-missing-regiment, viewed 16 July 2017.

[11] Yeni Şafak (Istanbul), 9 September 2013.

[14] For background: David Stephens, ‘Now that the Atatürk Memorial at Gallipoli is being restored … some options for President Erdoğan to consider’, Honest History, 18 June 2017, https://honesthistory.net.au/wp/stephens-david-now-that-the-ataturk-memorial-at-gallipoli-is-being-restored-some-options-for-president-erdogan-to-consider/, viewed 11 July 2017.

[15] Yeni Şafak, 25 April 2011.

[16] Bugün (Istanbul), 28 September 2013.

[17] See Robert Fisk, ‘The Gallipoli Centenary is a shameful attempt to hide the Armenian Holocaust’, The Independent (London), 19 January 2015, https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/comment/the-gallipoli-centenary-is-a-shameful-attempt-to-hide-the-armenian-holocaust-9988227.html, viewed 16 July 2017.

[18] David Stephens & Burçin Çakır, ‘Myth and history: The persistent “Atatürk words”’, David Stephens & Alison Broinowski, ed., The Honest History Book, NewSouth, Sydney, 2017, pp. 92-105.

Due to login difficulties, posted by admin on behalf of Harvey Broadbent, Balgowlah, NSW:

For me, Ayhan Aktar’s article, Rewriting the history of Gallipoli: a Turkish perspective, provided many interesting historical references, which I welcomed. One is always pleased to see what other researchers turn up, adding to the canon of documentation, even if you find yourself saying “I wish I’d seen that reference myself”! I am not interested in critiquing the article in detail, but, in general terms, his reference material for a few assertions was not substantial enough, in my view. I noticed a few assertions of the author that could be challenged. Having been subjected to this exercise in the past myself, I suppose this is common in the nature of writing history. Overall though for me, the article is valuable in bringing the contemporary aspects of the Gallipoli story into focus.