‘Democratic opposition to war: the 1916-17 anti-conscription campaigns – impacts and legacies (Keynote address, Brunswick-Coburg Anti-Conscription Commemoration Campaign Conference, 20 May 2017)’, Honest History, 13 June 2017

The conscription referendums as a turning point in Australian politics

I welcomed an opportunity to place the campaigns against conscription in 1916 and 1917 in context, and I look forward to hearing more substantial contributions throughout the day. I congratulate Michael Hamel-Green and his team for organising this conference, especially here in Brunswick, which played an important part in the campaigning.

John Wren (Age)

John Wren (Age)

Frank Anstey (1865-1940) was the federal MP for Bourke from 1910 to 1934, having previously been the state Member for Brunswick 1904-10. He was the only declared free-thinker in the overwhelmingly Catholic political machine of John Wren, and, much later, a co-investor. John Curtin (1885-1945), a lapsed Catholic and never in the Wren cohort, was closely associated with Anstey on many issues. He campaigned vigorously against conscription and was imprisoned, briefly, for failing to register for enlistment. Frank Hyett (1882-1919), an effective trade unionist, secretary of the Victorian Railways Union and an able cricketer, also campaigned with Anstey and Curtin; he died in the influenza pandemic just after the war. All three men lived in Brunswick.

Maurice McCrae Blackburn (1880-1944), educated at Melbourne Grammar and Melbourne University, also played an important role in the 1916 and 1917 referendum campaigns. Blackburn was state MP for Essendon 1914-17, and he lost his seat for his opposition to conscription. He returned to the Victorian Parliament in 1925, then in 1934 succeeded Anstey as federal MP for Bourke.

Expelled by the ALP in 1941, Blackburn became the only MP to vote against conscription in World War II and was defeated in the 1943 election. We will hear from Carolyn Rasmussen about Maurice and Doris Blackburn later.

Going to war

One of the most disturbing elements of Australia’s colonial history, rarely mentioned and almost never discussed, is the enthusiasm of colonists in the 19th century for participating in military adventures overseas, either as enthusiastic amateurs or by sending infantry and naval ships.

Australian colonists were first involved in the Maori Wars in New Zealand (1845-46, 1863-64); there were volunteers in the Crimean War (1854-56), in the Indian Mutiny (1857-58), and for both sides in the American Civil War (1861-65); then a contingent from New South Wales went to the Sudan (1885). Then followed the Boer War (1899-1902) and the Boxer Rebellion in China (1900-01), where – Wikipedia informs me – duties included providing members for firing squads. Were they volunteers or conscripts in this role?

Why this enthusiasm for involvement in war? There seems to have been some compelling sense that Australia’s colonists, at the end of the earth, would be forgotten unless they were seen to be involved: ‘Australia will be there’.

The Old Fort, Queenscliff, 1860 (Wikipedia)

The Old Fort, Queenscliff, 1860 (Wikipedia)

This attitude was matched by the enthusiasm shown for the building of forts to protect Australia from Russian invasion: Queenscliff in Victoria, Fort Largs in South Australia and Battery Point, near Hobart. The forts were to ensure that the Russians did not invade; I concede that this objective was successfully achieved.

No doubt a sense of adventure was another powerful factor for our eagerness to be involved. Later came an expectation that if we offered support to powerful friends, they would come to our aid if we were in trouble. This has been a continuing theme in our foreign policy and the rationale for our fighting in Malaya, Korea, Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan.

Every Western intervention in the Middle East in the past century (except for the creation of Israel in 1948, and this is still bitterly contested) has failed. It is wildly optimistic to assume that military action against Islamic State will be any more successful.

As Alison Broinowski writes in The Honest History Book (NewSouth, 2017), ‘Settler Australia had war in its genes … Australians have fought in 16 wars, half of them in Asia, but only once in defence of the continent itself against imminent invasion from Asia.’

Chronology

August 1914. Outbreak of World War I. Australia was automatically involved as part of the British Empire.

September 1914. Australian election, won by ALP. Andrew Fisher prime minister for the third time.

March 1915. Allied invasion of Turkey/Ottoman Empire at Gallipoli, followed by the landing of the ANZACs on 25 April.

October 1915. Fisher resigns. William Morris Hughes becomes Labor leader and prime minister.

December 1915-January 1916. Evacuation of Gallipoli

April 1916. Easter Rising in Dublin

July 1916. Battle of Fromelles

July-September 1916. Battle of Pozières

September 1916. Hughes expelled by NSW Branch of the ALP.

October 1916. First conscription referendum

November 1916. Hughes forms ‘National Labor Party’ supported by Opposition, then organises Coalition with Joseph Cook’s Liberals.

Hughes badge, c. 1917 (MOADOPH)

Hughes badge, c. 1917 (MOADOPH)

February 1917. Hughes remains as prime minister as leader of the Nationalist Party of Australia.

April 1917. The United States enters the war.

May 1917. Australian elections. Hughes and the Nationalists win 55 per cent of the vote.

November 1917. Lenin seizes power in Russia, which then, in effect, withdraws from the war. (Treaty of Brest-Litovsk March 1918.)

December 1917. Second conscription referendum.

November 1918. Armistice in Europe.

Hughes and the debauching of Australian politics

In the first 15 years after Federation there was a high level of co-operation, civility and openness between figures such as Barton, Deakin, Reid (up to a point), Chris Watson, Andrew Fisher, and Joseph Cook. There were ideological differences but election campaigns were conducted in a temperate fashion. As I read them, Deakin and Fisher would never make promises, claims or accusations that they could not substantiate. The party system was not firmly established, conservatives were divided between Free Traders and Protectionists, personal alliances were contingent and constantly changing.

The prime ministership of William Morris Hughes (1915-23) marks a turning point in the way Australian politics was run. Hughes forced Fisher out of the Labor leadership, split the ALP, founded the Nationalists (not to be confused with the current Nationals) and then proved to be a constant wrecker.

Hughes’ handling of the two referendums shows him at his worst. Allied troops had been withdrawn from Gallipoli in January 1916. Australian forces were still located in Egypt but most divisions were transferred to the Western Front, suffering heavy casualties at Fromelles and Pozières (July-September 1916). It was in this context that ‘Billy’ Hughes decided that Australia could only increase Australia’s contribution by imposing conscription.

Hughes’ enthusiasm for conscription for overseas service was supported by four of his Ministers but most members on the back bench, and in the trade unions, disagreed bitterly. Hughes lacked the numbers in the Senate (even with Opposition support) to amend the Defence Act 1903 to allow conscription for overseas service. (In 1916, the Australian Senate had 36 members, six from each state, elected by ‘first-past the post’ for six-year terms. In the normal course, half the Senate was elected every three years. However, the 1914 election had been a double dissolution and, in 1916, 31 of the 36 Senators were members of the ALP.)

By way of compromise Hughes proposed a referendum (in effect, a plebiscite but described as ‘referendum’ in the documentation) to measure public opinion on the subject. It would have been essentially advisory and not a ‘Constitutional referendum’ which amended the Constitution. It is a moot point as to what the High Court would have ruled if ‘Yes’ had won but the Senate had still rejected Hughes’ Bill.

The question at the first referendum (28 October 1916) was highly loaded, with the use of emotive language. It asked Australians:

Are you in favour of the Government having, in this grave emergency, the same compulsory powers over citizens in regard to requiring their military service, for the term of this War, outside the Commonwealth, as it now has in regard to military service within the Commonwealth?

The referendum result varied across the states. Western Australia (69.7 per cent) had the highest ‘Yes’ vote, followed by Tasmania (56.2) and Victoria (51.9). South Australia (57.6) voted ‘No’ strongly, followed by New South Wales (57.1) and Queensland (52.3).

Anti-conscriptionists selling photographs of Archbishop Mannix, Melbourne, 1917 (AWM P11677.001)

Anti-conscriptionists selling photographs of Archbishop Mannix, Melbourne, 1917 (AWM P11677.001)

In the course of the referendum campaign, Hughes effectively lost the support of Caucus and the Party machine, so in November he walked out (‘ratted’ as the Party still has it) with 24 Caucus colleagues, including four Ministers, and formed his own National Labor Party, retaining the prime ministership with Opposition support. In February 1917, Hughes created the Nationalist Party of Australia, in a merger with his former political adversaries in the Liberal Party.

As it turned out, after the May 1917 federal election Hughes commanded the support of 24 of 36 Senators. Half the Senate was up for election and Hughes’ Nationalists, with 55.4 per cent of the Senate vote, won all 18 seats.

The second referendum of 20 December 1917 asked:

Are you in favour of the proposal of the Commonwealth Government for reinforcing the Australian Imperial Force overseas?

The second time around, New South Wales (58.8 per cent), Queensland (56.0), South Australia (55.1) and Victoria (50.2) voted ‘No’, while Western Australia (64.4 per cent) and Tasmania (50.2) voted ‘Yes’.

I point to the paradox that Hughes loses both referendums but his Government is re-elected in a landslide in 1917 (7 per cent swing, 54.2 per cent of the total vote). My assumption, and it is no more than that, is that a significant number of women voted ‘No’ in the referendums but for Hughes in the election. They did not want their sons, husbands and brothers to be conscripted, but did not much care for the ALP.

Hughes unleashed the forces of sectarianism, digging a huge divide between Catholics and non-Catholics which lasted for decades. He broke the ALP, leading his Ministers (only one of them a Catholic) off to the Right. A spectacularly low point in Hughes’ career was using his numbers to expel the MP for Kalgoorlie, Hugh Mahon, from Parliament in November 1920 for attacking British policy in Ireland. Between 1916 and 1941, Labor had only two years in Government, at a time when Scullin faced the overpowering force of the Great Depression.

Hughes was a vicious campaigner. He would say anything. This ‘winner take all’ approach has dominated Australian politics for much of the century since the 1916 Labor split. Truth? It hardly mattered.

I can only think of four good things to be said of Hughes:

- He recognised that the British High Command was made up of duds and objected to Australian troops being under their direct control.

- He refused to allow the death penalty for deserters.

- He brought down the government of Stanley Melbourne Bruce in 1929.

- In the 1930s he was not just the first, but the only, senior Australian politician who recognised the radical threat of Hitler and that he could not be appeased.

There were some eerie similarities between Hughes and David Lloyd George: both were of Welsh descent and both were wreckers of their parties.

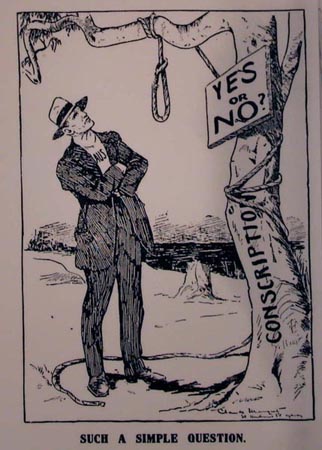

Anti-conscription cartoon, Australian Worker, 1917 (John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library/Claude Marquet)

Anti-conscription cartoon, Australian Worker, 1917 (John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library/Claude Marquet)

1916 and Ireland

The 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin marked the beginning of years of turmoil and bloodshed in Ireland, which was not resolved by the creation of the Irish Free State in 1922, and which went on until 1923. The political and personal divisions of the Civil War continued until the 1970s. The impact of the Easter Rising on Australia’s conscription votes is a subject of continuing controversy.

Archbishop Daniel Mannix was identified as a passionate advocate of Irish Home Rule. Less prominent in the 1916 Referendum, he was perhaps the dominant figure in the ‘No’ campaign in 1917, and was much attacked by Hughes. However, Mannix’s actions may have encouraged Protestant clergy to take a more active role on the other side in the ‘Yes’ campaign. The Catholic Archbishops of Sydney and Perth, both Irish born, also encouraged a ‘Yes’ vote but Catholic enclaves such as Koroit in Victoria voted ‘No’ overwhelmingly.

Gallipoli as Australia’s creation myth

Alan Bond hailed his win in the 1983 America’s Cup as being ‘the greatest Australian victory since Gallipoli’. Many Australians have come to feel the same way.

I have always resisted the dangerous belief, revived by John Howard and keenly promoted by Tony Abbott’s ‘Team Australia’, that Gallipoli is Australia’s great creation myth – White Australia’s, that is – and that the Anzac tragedy brought us together as a nation.

The Honest History Book, mentioned earlier, edited by David Stephens and Alison Broinowski, contains thoughtful essays analysing the significance of Gallipoli and the Anzac legend as a kind of civic religion in Australia. It convincingly demonstrates, too, that the noble statement attributed to Kemal Atatürk, paying homage to the war dead of both sides, is a fabrication, dating from 1953.

In World War I, Winston Churchill became convinced, after initially preferring a Baltic intervention, that an attack on Gallipoli would lead to speedy capture of Constantinople – as the West still called it, although the Muslim world called it Istanbul from 1453 – causing a domino effect. The Ottoman Empire would collapse, pressure would be taken off Russia, rising nationalism would break up the Habsburg Empire and the war would soon be over. The major players in the Gallipoli drama were all shaped by their personal history. They were victims of their own delusions too.

Attitudes towards World War I, and especially towards Gallipoli, have always been politically highly charged in Australia. In Britain, too, a major controversy erupted in 2015 over rival interpretations about justifications for the war and British involvement. Thousands of Australians each year visit Gallipoli for Anzac Day, far more than went 30 years ago. I suspect that relatively few of these visitors attempt to work out why we were there in 1915.

Why were we invading Turkey (or the Ottoman Empire, as it was then called)? Was it in response to some attack on us or threat to our survival? What issues were in contention between Australia and the Ottoman Empire in 1915? What threat did the Turks represent? None that I can think of.

It is hard to come up with a convincing justification. That the loss of life was tragic is not in doubt – but visitors to Gallipoli recognise the suffering on both sides. Gallipoli plays a central role in the national myths of Turkey and Australia, but not for Britain or France or New Zealand, which suffered greater losses, per head of population.

Gallipoli: the unmaking of a nation?

World War I knocked the stuffing out of Australia. It reinforced a sense that we were isolated, on our own, not able to cope without great and powerful friends.

Australia was a far more vital, optimistic and creative place in the 20 years before 1915 than in the two decades following it. Major reforms in 1895-1915 included Federation, votes for women, setting up Federal institutions, establishing the High Court and the Commonwealth Bank, the Arbitration system and the ‘Harvester judgment’, old age and invalidity pensions, the world’s first national Labour governments, Australian stamps and currency, exploring Antarctica, the Transcontinental railway, choosing Canberra as national capital, developments in science and education. There was a strong sense of independence and recognition of Australia as being a social laboratory.

Between 1915 and 1935, however, there was a long dip – both economic and psychological – in Australia. (Our gross domestic product per capita only returned to the 1913 level in 1938.) We became more defensive, anxious – more dependent on the British connection, derivative, and divided on sectarian lines. There was a failure of nerve. The progressive movement was crushed. Families were deformed by death, wounds, and psychological impairment.

Apart from the establishment of the CSIRO and the ABC, the inauguration of Canberra, and setting up the Commonwealth Grants Commission, it is hard to point to major reforms in that period 1915-35. The argument that Gallipoli was central to establishing a modern, confident, innovative Australia is demonstrably false. Australia deferred adoption of the Statute of Westminster 1931, which provided for Constitutional sovereignty, for fear of weakening the British connection.

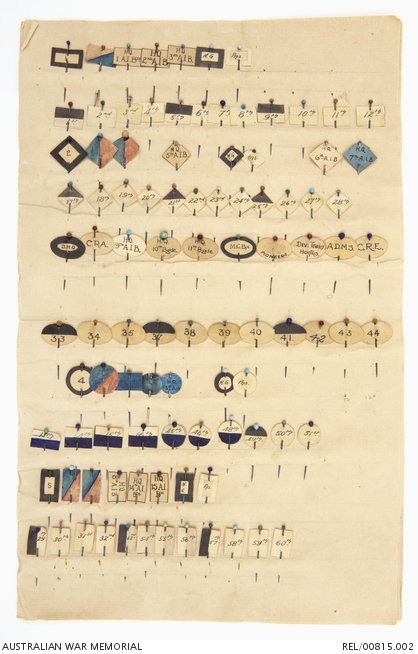

Pin flags used by Monash (AWM REL/00815.002)

Pin flags used by Monash (AWM REL/00815.002)

The reaction to the visit of the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VIII, to Australia in 1920 could only be described as hysterical. (His letters to his then mistress indicated that he hated it.) In the same year, General Sir William Birdwood, the British officer who commanded the ANZAC Corps, was honoured in the Australian Parliament – a distinction never given to Sir John Monash. The Government of Stanley Melbourne Bruce, which made Birdwood a Field Marshal in the Australian Forces in 1925, refused to promote Monash from Lieutenant General to General. (Scullin promoted him in 1929.)

Finally, overemphasis on Gallipoli has led to a failure to grasp the significance of Australia’s success story on the Western Front in 1918 – as Ross McMullin argues – in which John Monash played a central role. Field Marshal Montgomery thought Monash was ‘the best general on the western front in Europe’.

Barry Jones AC was a state and federal Labor MP, Commonwealth Minister and National President of the ALP. He has written a number of books and is one of the National Trust’s Australian Living Treasures. He is the only person to have been elected as a Fellow of all four Australian Learned Academies. Honest History thanks him for allowing us to reproduce his keynote address here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.