‘Reply to Marilyn Lake’s review of Best We Forget: The War for White Australia, 1914-18’, Honest History, 16 November 2018 updated

Marilyn Lake’s review of Best We Forget: The War for White Australia, 1914-18 appeared in Australian Book Review, August 2018. It was featured as ‘Review of the Month’.

Marilyn Lake’s review of Best We Forget: The War for White Australia, 1914-18 appeared in Australian Book Review, August 2018. It was featured as ‘Review of the Month’.

There are paragraphs in the review which discourse on matters of nation, race and war, but where Lake engages with argument in Best We Forget she is mostly wrong and thus, mostly, misleading.

It is my belief that uncomplimentary reviews should generally be ignored but, consistent with the European tradition, polite silence can be set aside when a review thoroughly misrepresents the work in question. I want to address four of Lake’s propositions.

I: ‘Not primarily…’

At the outset Lake suggests that I’m arguing Australia went to war in 1914 ‘not primarily to support the Mother Country in fighting German militarism, but rather to secure the goals of White Australia’. Here is evidence to the contrary:

The primary objective, of course, was the defeat of Germany, the survival of Britain and the empire, and the maintenance of those strategic, economic and sentimental ties that most Australians cherished. (p. 9)

Yet Lake persists, claiming that I go on ‘to make the case’ for an argument I have not proposed. Numerous quotations from Best We Forget might serve the purpose but here is just one more:

Government and the Opposition were entirely committed, by bonds of blood and culture, to Britain’s fight against Germany, understanding the dire implications for Australia should the war be lost. But they were also frustrated, hugely so, by Japan’s rise to power under the aegis of Britain, and by what appeared to be no real understanding – still – in London of Australia’s peril. For Britain, the enemy was Germany. For Australia it was Germany and, inevitably, Japan. (p. 176)

Here and there I refer to the ‘underlying strategic context’, to the ‘strategic dilemma’ and to the ‘story behind the story’, but nothing, it appears, will unsettle Lake’s conviction.

II: What is ‘lost to memory’?

The Anglo-Japanese alliance of 1905 was seen positively – in Britain (Wikipedia/Punch)

The Anglo-Japanese alliance of 1905 was seen positively – in Britain (Wikipedia/Punch)

The second misreading is one of those compounding errors that begins with a false assertion and from there can only get worse. Lake claims as follows:

To make his case, Cochrane summarises many decades of historical scholarship on the White Australia policy, documenting racial preoccupations that, he asserts, somewhat tendentiously, have been “lost to memory”. This is an odd claim in many ways, because perhaps one of the few things most Australians remember from our national history is that among the first measures passed in 1901 by the new Commonwealth was the race-based Immigration Restriction Act, which established the White Australia policy.

Let’s just work through the sequence of errors here, perhaps best described as a compounding travesty:

- Nowhere in Best We Forget do I summarise ‘many decades of historical scholarship on the White Australia policy’.

- Nowhere in Best We Forget is there the suggestion that the White Australia policy was or is ‘lost to memory’. The entire book hinges on the understanding that White Australia was vivid in the minds of Australians in general and their leaders in particular.

- And nowhere in Best We Forget do I suggest that the ‘racial preoccupations’ of ‘most Australians’ were ‘lost to memory’.

My phrase ‘lost to memory’ appears in the Introduction, where I pose a number of questions which subsequent chapters address. It is easy for a reviewer to contend by way of selective observation and to generalise where only the particular will do, but an honest evaluation of ‘lost to memory’ would at least attempt to appreciate that phrase in the context of the paragraph in full. I wrote as follows:

Why have the racial preoccupations that shaped Australia’s preparation for and subsequent commitment to war been lost to memory? Why has the obsession with the Pacific and race purity, with Japan in particular – an obsession stretching from colonial times to the Paris Peace Conference of 1919-20 and beyond – escaped recall? Why has the racial dimension of the strategic thinking of Australia’s leaders been lost to posterity? Why does our collective remembrance contain not the faintest notion that the nation’s war was, in no small part, a war for white Australia? (p. 3; emphasis added)

‘Lost to memory’ is a reference to what Best We Forget is about: ‘the racial dimension of the strategic thinking of Australia’s leaders’, notably their obsession with Japan. ‘Lost to memory’ is referencing ‘the war for White Australia’, not the well-remembered White Australia policy. This is an argument about the racial dimension that figured powerfully in the preparation for the war and the prosecution of war, and how and why that has slipped from popular memory. Lake moves from one false claim to another. She is lost in the general (‘most Australians’, ‘racial preoccupations’) and blind to the particular.

At another point in her review, Lake seems to think the book is about motives for enlistment. She writes a long paragraph on enlistment, arguing as follows: ‘But of course it was not just, or even primarily, “race fear” that persuaded Australians to enlist, it was also “race pride”’. The paragraph goes on and on about why ‘young Australians’ enlisted.

What ‘young Australians’ were thinking about enlistment, and how ‘race pride’ may have figured in their thinking, is quite simply outside the parameters of Best We Forget. It is irrelevant. What Australia’s leaders were saying about enlistment – in the chapter called ‘War and Peace’ – is another matter. But Lake shows no interest in that.

III: ‘History will never beat myth.’ No?

Handmade illuminated address from returned soldiers in Brisbane, presented to Prime Minister Hughes in 1919, thanking him for his work ‘for the preservation of a White Australia’. The address is reproduced in Peter Stanley, The Crying Years, pp. 220-21 (WM Hughes Papers National Library of Australia, MS 1538, series 16.3, file 4868 entitled ‘Illuminated address to WMH from the Brisbane RSL sub branch October 1919’)

Handmade illuminated address from returned soldiers in Brisbane, presented to Prime Minister Hughes in 1919, thanking him for his work ‘for the preservation of a White Australia’. The address is reproduced in Peter Stanley, The Crying Years, pp. 220-21 (WM Hughes Papers National Library of Australia, MS 1538, series 16.3, file 4868 entitled ‘Illuminated address to WMH from the Brisbane RSL sub branch October 1919’)

The third false claim is as misguided as the litany of errors in the second. Lake cites my reference to the late John Hirst’s belief that ‘history will never beat myth’ and from there proceeds to argue that this is my position, claiming that I seem ‘to concede defeat in the face of popular “storylines”’. She cites what she calls my ‘lament’:

Contemporary politics, he laments, plays a larger part than scholarly history, a “decisive” part, in shaping popular memory.

The misreading here is entirely at odds with the argument in Best We Forget and, indeed, with the purpose of the book.

Most readers will note the epigraph at the beginning of my book, the words of a great historian, Inga Clendinnen: ‘In human affairs, there is never a single narrative. There is always one counter-story, and usually several, and in a democracy you will probably get to hear them.’ In the final chapter, on the politics of popular memory, I quote that Clendinnen passage again. I argue that in democracies there is plenty of room for contention and controversy and for history to win out, at least in the long run. I say this:

But in democracies, at least – where we are still free to argue, even if the rhetorical forces of romance and sentiment outweigh the forces of critical restoration – there is room for contention and controversy, for argument about what is the more appropriate or valid narrative for a modern nation, a mature nation. What that nation remembers can and does change, but only with vigorous debate and only when the conditions are ripe for change. Uncomfortable truths are not easily resurrected, but this can happen with the eruption of formerly unheard or marginalised voices, or with the piecemeal accumulation of scholarship over time. Or both. (pp. 223-24; emphasis added)

In other words, my take on history and national mythology is entirely contrary to what Lake is telling the readers of Australian Book Review. The vital sentence should be clear, but I will repeat it:

Uncomfortable truths are not easily resurrected, but this can happen with the eruption of formerly unheard or marginalised voices, or with the piecemeal accumulation of scholarship over time.

I do not concede defeat in the face of popular storylines. History can and does win out, but it’s no easy battle, as the quotation in full suggests.

The point of my argument is hard to overlook. We saw in 1988, for instance, the rallying of marginal Aboriginal voices and others against the Bicentennial celebrations. We saw how they combined with the work of distinguished historians over previous decades, and the recovery of so much Indigenous and cross-cultural colonial history that popular memory was transformed. 1988 became a flash-point. The nation began to see another story, another ‘story behind the story’, history contending openly and widely in the popular domain, and perhaps even prevailing over popular storylines.

1988 protest (GreenLeft)

1988 protest (GreenLeft)

Similarly, it is my view that several generations of cumulative scholarship on race fear in this country – what I’ve called ‘the core historiography’ – will impact on the popular memory of World War I. It happens to be the main reason I wrote the book. Best We Forget is itself a chapter in history’s rejoinder, as the questions I pose on the penultimate page suggest:

Should we continue to commemorate and celebrate the First World War in the ways that we do, blinkered and sanitised, free of its racial context and racial core? Or should we see the war for what it was – not only a war against Germany and its allies, but a race war which prefigured the nation’s arduous transition to an acceptance that all of us, regardless of colour, share a common and equal humanity? (pp. 228-29)

IV: The complicity of historians

Lake claims that I have not acknowledged the complicity of historians ‘in ceaselessly shoring up’ the perpetual commemoration of the Anzacs. Here is more of Lake on this subject and my supposed ‘lament’:

In his concluding chapter on the politics of popular memory, Cochrane, the embattled historian, seems to concede defeat in the face of popular “storylines”. Contemporary politics, he laments, plays a larger part than scholarly history, a “decisive” part, in shaping popular memory. But perhaps it is the conceptual opposition drawn between history and memory – or history and myth – that is part of the problem, as it disavows the complicity of so many historians, in the present as well as in the past, in ceaselessly shoring up, in the author’s final words, the “perpetual commemoration of the Anzacs”.

Lake’s critique of ‘the conceptual opposition drawn between history and memory’ is commendable. The problem is, it does not apply here. On the contrary.

The complicity of historians in national myth-making is a subject with a significant presence in Best We Forget. In the case of CEW Bean, in both chapter one and the final chapter on the politics of popular memory, there are several pages on this complicity. Here is just a moment from each of those chapters:

He [Bean] would embark upon the Official History committed to an account of the war which, it would appear, deliberately ignored the elephant in the room. He would write a history that confirmed a perfect alignment of national and imperial interests, and he would evade the strategic significance of Japanese militarisation in the shaping of Australia’s war … He would provide a great account of soldiers at war, set in a censored strategic framework. (p. 15)

And

Historians have noted that Bean’s Official History was unusual in that it was subject to no censorship. But, as Ken Inglis observes, “the author nevertheless imposed a sort of censorship on himself, by omitting nasty details”. Inglis is referring to the gory horrors of the battlefield and painful truths associated with less-than-competent leadership, but the self-censorship went far further than the battlefield. Bean would write his six volumes and would oversee the rest, never permitting more than a hint of the underlying strategic context to appear … The buried history of race fear in the scholarship of the war begins with the official historian. (pp. 215-16; emphasis added)

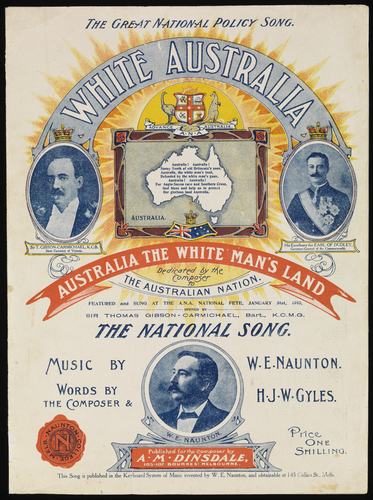

Sheet music, 1910 (Museum Victoria).

Sheet music, 1910 (Museum Victoria).

Lake’s commentary manages to mention Bean four times without in any way acknowledging how this particular ‘complicity’ – Bean’s complicity – is spelt out in the first and the final chapter of Best We Forget.

In that final chapter readers will also find evidence for the way in which other historians, apart from Bean, have been complicit in shoring up the national mythology of the First World War. The relevant argument can be found at pages 221-26.

It begins with an account of ‘the memory-makers’, select journalists, shock-jocks, politicians &c., who ‘reduce war to a powerful story of the nobility and horror of it all’ (p. 221). The text then goes on to discuss the ‘forces of critical restoration’ (p. 223) and then returns to the matter of ‘complicit’ historians. That is the arc of the argument, briefly set out for a general readership. What is on page 221 must be considered with what follows on the next page, and the one after that &c. On page 226, I refer to the opposition of ‘a small number of historians who are wedded to the narrative of imperial solidarity and the absence of Asia that prevails in popular memory’. I then provide several examples.

It is entirely incorrect for Lake to suggest that Best We Forget disavows the complicity of historians in national myth-making. On the matter of complicity, we are in broad agreement.

Peripheral matters

In her discussion of the wartime journalists who figure in Best We Forget Lake cites the wrong Murdoch. It’s Keith, not Walter. Keith and Walter were chalk and cheese. Keith Murdoch has a significant presence in the text. He figures prominently, twenty-four times in fact. Walter does not figure at all.

But this is a peripheral matter, as is Lake’s interest in the ranking of ‘things’: according to Lake, I suggest the ‘main thing wrong with the Anzac legend is that it pays no heed to the racial obsessions that drove Australian participation in the war’, yet nowhere in Best We Forget do I rank the ‘things’ that are wrong with the Anzac Legend, nor do I suggest my subject is the ‘main thing.’ The ranking of these ‘things’ is not relevant to Best We Forget.

Historians study and interrogate popular memory because it is an important instrument of power. Its claims and uses must be regularly subject to critical evaluation. That, plainly, is the purpose of Best We Forget.

* Peter Cochrane’s novel The Making of Martin Sparrow (Penguin-Viking) was also published in May this year. The Italian edition will be published in 2019. A review by Dennis Haskell considers the historian writing in the realm of fiction. Another review in Australian Book Review by David Whish-Wilson.

Notes from Honest History editor David Stephens

(1) Australian Book Review, September 2018, contains an exchange between Peter Cochrane and Marilyn Lake which canvasses some of the issues raised above.

(2) Peter Stanley’s review of Best We Forget for Honest History. Other material on Cochrane’s book.

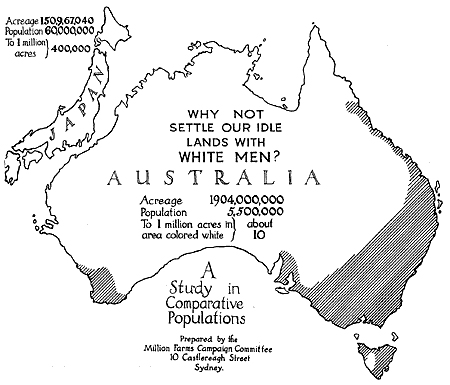

Advertising from the Million Farms Campaign Committee, c. 1921 (NAA)

Advertising from the Million Farms Campaign Committee, c. 1921 (NAA)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.