‘The most important book on Australia and the Great War’, Honest History, 7 October 2018

Peter Stanley reviews Peter Cochrane’s Best We Forget: The War for White Australia, 1914-18

The Great War centenary has seen a goodly trickle – though not the flood we anticipated – of books about Australia’s part in the Great War. We have seen important books on the operational side of the war (Meleah Hampton on the Australians on the Somme, say, or Lucas Jordan on ‘stealth-raiding’) and on the experience of war (Greg Raffin exposing the 1st Battalion protest to scrutiny or Joan Beaumont and her co-authors in Serving Our Country revealing the war experience of Indigenous communities).

Yet, no one (not even Beaumont in her prize-winning 2013 Broken Nation) has fully answered the biggest question of all: why did Australia become involved in such a ruinous conflict, seemingly without a second thought? The conventional answers to that question have been ‘because as a part of the British Empire Australia had no choice, and anyway went willingly’ or ‘no one could have known what the war would bring’. Both of those responses are true, but only up to a point.

Yet, no one (not even Beaumont in her prize-winning 2013 Broken Nation) has fully answered the biggest question of all: why did Australia become involved in such a ruinous conflict, seemingly without a second thought? The conventional answers to that question have been ‘because as a part of the British Empire Australia had no choice, and anyway went willingly’ or ‘no one could have known what the war would bring’. Both of those responses are true, but only up to a point.

Peter Cochrane is an independent scholar who has published widely on aspects of Australian history, including penetrating books on Simpson and his donkey and New South Wales colonial politics, and a couple of historical novels. Now, his Best We Forget is, quite simply, the most important book on Australia and the Great War to appear in the course of the war’s centenary.

Australians’ racial anxieties and antipathies in the late colonial and early federal period are, of course, well known and documented, as are their effects in making a White Australia one of the earliest and most durable creations of a national parliament, and in sending successive Australian governments off in the ‘search for security in the Pacific’, as one of the most substantial scholarly studies of the period was entitled. So what is new about Peter Cochrane’s book?

Cochrane shows that key members of successive Australian governments decided in the decade before 1914 that, when war came (as all expected it would), Australia would go ‘into this conflict for our own national safety’, as Billy Hughes said in 1919. That ‘national security’ was not conceived with a remote and notional German threat in mind, but with a conviction that a ‘race war’ would begin in the Pacific and that Japan would become an enemy.

Cochrane’s work endorses and elaborates the research of John Mordike, who in two books, An Army for a Nation (1992) and We Should Do This Thing Quietly (2002), showed how Australian politicians were willingly co-opted at imperial conferences before 1914 to commit troops to the Empire. These decisions remained unknown for some 80 years. Mordike’s argument, warily regarded or even rejected by more cautious historians, is complemented by Cochrane’s book. And we need to acknowledge the strength of Douglas Newton’s 2014 book, Hell-Bent, on the Australian decision to accept (and indeed anticipate) the Empire’s war in 1914, a work which likewise confirms and corroborates much of Cochrane’s argument.

Cochrane avers that his title Best We Forget is ironic. It is certainly ironic that, in over a century of writing about the Great War in all the dimensions in which we have, we – Australians – should have missed the essential facts as Peter Cochrane has found them. His argument is, in essence, that Australians’ racial anxiety toward Asia in general and Japan in particular in the decade before 1914 made Australia’s political leaders prepared to underwrite an imperial war in the hope of securing British support for the security of a White Australia.

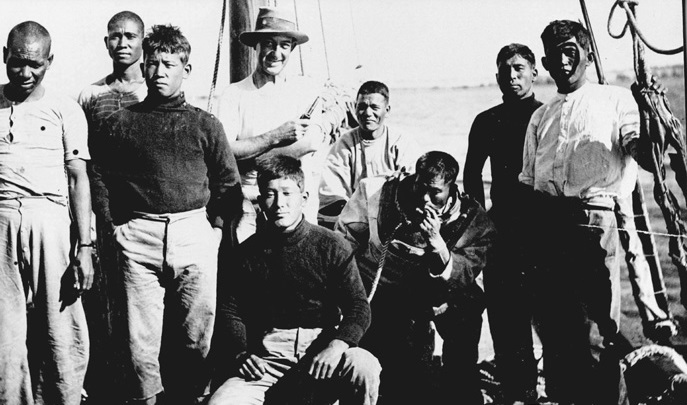

Japanese and other pearl divers, Broome, c. 1915 (AnzacPortal)

Japanese and other pearl divers, Broome, c. 1915 (AnzacPortal)

Cochrane supports his contention beyond question. Future historians of the Great War, while avoiding the easy characterisation of Australia as a prematurely ‘independent’ nation, can no longer find refuge or solace in its standing as a part of the British Empire. Australia’s membership of the Empire is part of the story, but not, as Cochrane shows, the whole explanation. ‘Popular memory’ of the war in Australia, he writes, has hitherto known ‘little or nothing of the racial dimension’ of the thinking and decisions underpinning the Australian decision to so enthusiastically commit to support the Empire. That now has to change. The next popular history of Australia’s Great War must acknowledge this fact.

One of the most important changes that Cochrane’s book has precipitated is that he shows that Charles Bean’s Official History, while perhaps not fostering outright lies, certainly presented a misleading view of events before and during 1914. It did this not least by failing to explain the importance of Australian apprehensions of Japan, despite Bean himself sharing those fears, as is clear from his published writing before the war. Did Bean really not know of the thinking that led to the decision to embrace the war so fully, or was he dissembling?

Cochrane has made the original and profound connection between Australian racial fears and its participation in the Great War. This is something that – amazingly – no-one else has done, despite the abundant literature on all of the historiographical strands from which Cochrane spins his yarn.

Cochrane’s is a most original and illuminating argument. It is perhaps more complex than it needs to be to provide a popularly accessible survey of the subject – Cochrane’s aim – but the detail strengthens his case. He takes the reader through late colonial Australia’s generalised racial antipathy, its eventual focus on the spectre of a resurgent Japan, and the anxieties of Australians conscious of their vulnerability and frustrated that Britain, their supposed protector, seemed unwilling or unable to fulfil that role.

Cochrane’s focus is ultimately to explore the question of why all this was so. His answer is to argue that the creation and dispatch of an expeditionary force (one that suffered the death of one in five of its members and the wounding of half the rest) was based not only – or not so much – upon simple imperial loyalty, but upon the quite deliberate trading of the lives of Australian citizen soldiers for an assurance that Britain would thereby undertake to protect a nervous, vulnerable White Australia, anxious over potential Japanese aggression.

Come the outbreak of the expected Great War the chief villain emerges, in the figure of William Morris Hughes, the self-proclaimed ‘Little Digger’, whose portrait adorns the book’s cover. Cochrane argues that Hughes changed his mind to seek conscription in order to demonstrate Australia’s bona fides. In this he was aided by Defence Minister George Pearce, who had been implicated in promises made at imperial conferences and who was now responsible for creating and maintaining an Australian Imperial Force.

Thus, Australia’s seemingly pointless sacrifices on the Somme and at Passchendaele were, Cochrane shows, made in order to guarantee a White Australia. The sixty thousand Australian dead Hughes famously claimed to speak for at Versailles were the premium Australia paid for what Hughes hoped would be an imperial guarantee, one that in the event was not honoured as Hughes and Pearce had hoped.

Pearce (Wikipedia)

Pearce (Wikipedia)

Cochrane’s case, if overly detailed, is clear and convincing. We can no longer continue to simply argue that ‘Australasian Britons’ simply responded to the appeal of Empire. They did – that was what made Hughes’s and Pearce’s task all the easier – but, in their motivations and – the word is unavoidable – machinations, the decisions of successive Australian governments, Labor and Liberal, committed their nation to a tragedy in order (in their view) to forestall the greater threat of an aggressive, imperialist Japan.

These governments were, of course, twenty-odd years previous, and the Australian crisis of 1942 when it came had to an extent been exacerbated by Hughes’s rhetoric and actions at Versailles. Arguably, Australia did eventually fight a ‘race war’ in the Pacific, but the losses suffered in the Great War did little or nothing to forestall it.

To end, a disclaimer: I read parts of this salutary book in manuscript, am thanked by the author in his acknowledgments and contributed a puff to its publisher (as did half-a-dozen other historians). Despite having tipped my hand, as it were, I do not consider that I am disqualified from offering a review of it. (Nor do we. HH)

* Professor Peter Stanley of UNSW Canberra is one of Australia’s leading historians of the Great War. As well, in 2008 he published Invading Australia: Japan and the Battle for Australia, 1942, in which he explained the long roots of Australian apprehension of Japan, and in 2017 The Crying Years, a history of Australia’s Great War that could have benefitted from Best We Forget.

On reading John Mordike’s reply to Peter Stanley’s above review of Peter Cochrane’s, Best We Forget: the War for White Australia (2018), I decided to offer the following thoughts.

Telling us that the Great War centenary has only seen a ‘goodly trickle’ of books, not the expected flood, Stanley’s review not only pulls Cochrane’s book out of the trickle, but describes it as ‘the most important book on Australia and the Great War’.

Measures of these matters no doubt differ. So, helpfully, Stanley offers us his measure, even though it is unbelievable: ‘Cochrane has made the original and profound connection between Australian racial fears and its participation in the Great War. That is something that – amazingly – no-one else has done …’. This is wrong. As Mordike says, his work made that ‘original and profound connection.’

Clearly, Cochrane’s book is a culling of secondary sources for a popular audience. While the work is leavened with a smattering of easily accessible primary sources, its secondary nature is unmistakable. It also rests on the questionable assumption of a ‘core historiography’, as Marilyn Lake’s review of Best We Forget (ABR, August 2018, no. 403) also perceives. The fireworks in Humphrey McQueen’s polemical writing has no doubt inspired Cochrane’s. The main primary source-based works apart from Mordike’s that seriously underpin Cochrane’s key themes are those relatively few he lists in the bibliography by Charles Bean, David Sissons, Neville Meaney and David Walker. We will also come to two essays by me that foreshadow the subject of his ‘War for White Australia’. There is the argument that Cochrane has created the illusion of a ‘core historiography’ to pump up his project.

Remarkably, then, Stanley, a ‘Past Pres.’ of Honest History, with its rather robust mission statement – of ‘supporting the balanced and honest presentation and use of Australian history’ – does not know a secondary source history when he sees one. Patently, his review subordinates to Cochrane’s work the important and splendid primary historical research of others including in Douglas Newton’s Hell-bent: Australia’s leap into the Great War (2014) and Meleah Hampton’s Attack on the Somme: 1st Anzac Corps and the Battle of Pozières Ridge, 1916 (2016) https://sydneyreviewofbooks.com/contributors/greg-lockhart .

Stanley’s most startling lapse of judgement, however, is that he misses the unsurpassed originality and general importance in post-1945 Australian military historiography of Mordike’s two books. Grounded in a comprehensive and meticulous reading of original primary documents in British and Australian records his books are: Army for a Nation: a history of Australian military developments, 1880-1914 (1992) and, indicating in the subtitle the ‘original and profound connection’ Stanley now attributes to Cochrane, ‘We should do this thing quietly’: Japan and the great deception in Australian defence policy 1911-1914 (2002).

Manifestly subordinating the importance of Mordike’s work to Cochrane’s, Stanley then says Cochrane has ‘endorsed and elaborated’ it – we won’t ask exactly how. Anyway, Stanley sums up Mordike’s work himself : it ‘showed how Australian politicians were willingly co-opted at imperial conferences before 1914 to commit troops to the Empire. These decisions remained unknown for some 80 years.’ This is a welcome statement. At the same time, Stanley’s review of the Cochrane still mutes the major change from imperial to national perspective that Mordike’s research embodied in Australian military writing, and Cochrane does not sufficiently focus. It also completely misses Mordike’s originality in the key area it unwisely attributes to Cochrane: the integration of Australian racial fears into the evolution of defence policy in 1911-1914.

There was no way Mordike could have written Army for a Nation without that assumption. Far from fear of Germany, as the standard imperial romance maintains, his discussion revolves around the fear of Australian leaders that, unless they supported the British in their wars anywhere, the Royal Navy might not be available to defend ‘white Australia’ when the ‘yellow peril’ of particularly Japan inevitably materialised.

Subtitled Japan and the great deception in Australian defence policy 1911-1914, Mordike’s ‘We should do this thing quietly’ (2002) is an indispensable companion to Army for a Nation. In the acknowledgements to that book, Mordike wrote: ‘While writing this monograph, I have had countless hours of discussion with Dr Greg Lockhart. This time was stimulating and proved particularly helpful in developing an understanding of the fundamental relationship between “White” Australia and defence.’ By way of explanation, when we started talking I had for over twenty years been working in Asian, particularly Vietnamese history. So much in any case for Stanley’s claim of Cochrane’s ‘original and profound connection’ between those things when ‘We should do this thing quietly’ goes on to present more important primary research and develop the argument in his first book.

While Stanley misses all this, Mordike is well within bounds to reply to Stanley’s review by saying that there is ‘simply no doubt about who did the pioneering work’ on the connection between unwarranted fear of Japan and our participation in the Great War; i.e. Mordike did. And ‘what is amazing’, Mordike’s last sentence says, is that ‘other Australian historians, except for Greg Lockhart – “Race Fear, dangerous denial”, Griffith Review 32, https://griffithreview.com/articles/race-fear-dangerous-denial/ seem to know nothing about it.’

There was an exception: Cochrane, who knew something about it about it from reading ‘Race fear’, which he lists in his bibliography, and from discussing it with me. As indicated, though, unlike Mordike he mishandles his citations of ‘Race fear’ and another of my essays.

As it happens, Cochrane omits to mention ‘Race fear’ in his notes – note 19, p. 249 would have been the most fitting place, because there, to support his own discussion of Mordike’s work, he cites the endorsements of it by David Walker and Douglas Newton, both of whom, you cannot tell from Cochrane’s comment, acknowledge that their understanding of Mordike’s work stems from my critique of it in ‘Race fear’. The other point would be that, while not noting ‘Race fear’, and perhaps not fully understanding it, Cochrane uses the term ‘race fear’ frequently in his book.

My other essay, which Cochrane has read and discussed with me and then mishandled is ‘Absenting Asia’, in David Walker and Agnieszka Sobocinska eds, Australia’s Asia: from yellow peril to Asian century, (2012). This time, the mishandling involves the omission of the title – in note 20, p. 259. Therein Cochrane references ‘Greg Lockhart’s essay’ without naming it ‘in Walker and Sobocinska (eds), Australia’s Asia’ – while noting by contrast the names of other essays he uses in that volume by Walker and Greg Watters. And what has gone missing in that way? The title of a work that foreshadows and focuses the main thrust of Cochrane’s book, as I have elaborated elsewhere today: https://johnmenadue.com/greg-lockhart-on-reading-peter-stanleys-review-of-peter-cochranes-best-we-forget/ .

Even as they point to a pumped up project, Stanley might be forgiven for missing some of the fine points here. Nonetheless, Mordike notes reasonably that, in view of a glaring fact, he is ‘baffled – and upset’ by Stanley’s review of Cochrane’s work. The fact is that on 8 May 2018, some four months before Best We Forget came out, Stanley had invited Mordike to give a paper on the main elements of his work at an Australian Defence Force Academy Symposium. At the Symposium I also gave an address, which centred on the silence in the military literature to this day about the fact that ‘White Australia’ was the basis for Australian defence at any time from 1901 to 1914 and well after.

Mordike’s frustration is understandable. I am not, however, baffled and upset. I think that, while doing our best to call out nonsense, we must also dream. Because, especially when the cat is out of the bag, the evidence suggests we shouldn’t expect too much balanced and honest history – whatever that is.

Peter Stanley writes that: ‘Cochrane has made the original and profound connection between Australian racial fears and its participation in the Great War. That is something that – amazingly – no-one else has done, despite the abundant literature on all of the historiographical strands from which Cochrane spins his yarn.’

Stanley’s comment is wrong.

I made the original connection – and it was comprehensively researched and documented – in “‘We should do this thing quietly’: Japan and the Great deception in Australian defence policy 1911-1914.’

This book was published in 2002.

Peter Cochrane’s method of citation of evidence in ‘Best We Forget’ might lead readers to think that he has analysed the primary sources; he cites those primary sources first and then cites my work from which the primary sources are taken, as a secondary source. It is unfortunate that Cochrane has chosen this style because I believe that it can lead to misunderstandings like Stanley seems to have made.

Yet Stanley’s comment still leaves questions, because, in the text of ‘Best We Forget’, Cochrane acknowledged my scholarship in analysing the minutes of the Committee of Imperial Defence and the files of the War Office to establish the Japanese connection. It is a complex issue that is only resolved by extensive research on primary sources held in the United Kingdom.

Significantly, in 1910-1911, British strategists spent many months developing a plan to use Australia’s race-fear of Japan to motivate Australia to begin costly preparations for war; the documentary trail is long and detailed. The issue that had long frustrated Britain was that Australia had formally declined participation in imperial military proposals in 1897, 1902 and 1907. Alfred Deakin’s Universal Military Training scheme, which was being introduced in 1911, was also focused entirely on the defence of Australia. The British strategists determined that they had to find a way to involve Australia in imperial military operations, the most critical issue being the early development of war materiel to equip the force. The matter needed urgent attention. Since 1909, senior officers in the War Office had been planning a contingency where British forces would combine with French forces to oppose a German advance in Belgium.

At the Imperial Conference of 1911, Prime Minister Andrew Fisher, Defence Minister Senator George Pearce and Foreign Affairs Minster Egerton Batchelor were told by the British strategists that they believed Japan was preparing to attack Australia in 1915. This was a pure fabrication, intended to frighten the Australians into developing a strong military capability which the British strategists envisaged would be deployed in Europe. But, at the same time, the British strategists took care not to mention the possibility of a European war in case such a prospect might alarm the Australians, leading them to develop a more independent national defence strategy. British Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey told the Australian delegates and others at the Imperial Conference of 1911 that Germany was ‘genuinely anxious to be on good terms with us, and we smooth over the matters which arise between us without difficulty’. The prospect of war with Germany was deliberately down-played.

The trap was set and it worked. On 17 June 1911, Pearce, overcome with fear of Japan, assured the British Chief of the General Staff Sir William Nicholson that Australia would begin the planning and preparation of an expeditionary force to fight under British control. Nicholson did not tell Pearce where he thought the expeditionary force might be deployed and the Australian did not ask. Fisher, Pearce and Batchelor thought that because they were embracing the British military strategy then the Royal Navy would defend Australia when the Japanese attack came. That is what they were led to believe. The only condition that Pearce placed on preparation of the Australian expeditionary force was that it be kept secret. Nicholson responded with the comment that: ‘We should do this thing quietly’. And it was kept secret. Even to the extent that Bean fabricated a cover-up in his official history. The unpalatable, but inescapable, truth is that the First Australian Imperial Force was conceived in deceit. Australians never knew about this until my first book was published in 1992.

Returning to Stanley’s review, I am baffled – and upset – by his assertion that Cochrane has made the original connection between Australia’s race fear and the Great War. I delivered a paper at a Great War seminar convened in the Australian Defence Force Academy in May this year. I spoke about this very issue and left no doubt that my paper was based on research that had been published in 1992, ‘An Army for a Nation’, and in 2002, ‘”We should do this thing quietly”‘. Indeed, Stanley has been editing my paper for publication. I believe this will happen before Christmas.

There is simply no doubt about who did the extensive pioneering work on this subject and when it was published. What is amazing is that other Australian historians, except for Greg Lockhart – ‘Race Fear, dangerous denial’, Griffith Review 32, Autumn 2011, seem to know nothing about it.