‘The unauthorised biography of a legend’, Honest History, 15 September 2014

Frank Bongiorno reviews Carolyn Holbrook, Anzac, the Unauthorised Biography, NewSouth, Sydney, 2014. See also speeches by Stuart Macintyre and the author at the Melbourne launch of the book.

_________________

It is surprising, when you consider how many words about Anzac are published even just every April, how much we still do not know about it. Popular military histories of Australians at war there are aplenty but they rarely have much to say about the history of Anzac itself as a national mythology. And, when they do venture into this territory, they frequently do little other than repeat the clichés to which we have all become increasingly accustomed.

Charles Bean and Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett, Imbros, 1915 (Australian War Memorial A05382)

Charles Bean and Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett, Imbros, 1915 (Australian War Memorial A05382)We still, for instance, have neither a general history of Anzac Day nor, despite some valuable studies of aspects of his life and work, a major biography of Charles Bean. Ken Inglis’s Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape has a towering status in the historiography, not only because of its high quality and its author’s position as the modern pioneer in the field of Anzac history, but also because it is one of the few places one can go for the kind of breadth, in terms both of periodisation and perspective, we so desperately need. Then, Alistair Thomson’s Anzac Memories: Living with the Legend, Graham Seal’s Inventing Anzac: The Digger and National Mythology and Bruce Scates’s Return to Gallipoli: Walking the Battlefields of the Great War also have what Keith Hancock called ‘span’, alongside their particular concerns with cultural memory, popular culture and battlefield pilgrimage respectively.

But, in general, bold synthesis and broad brushstrokes have not been a feature of historical writing on Anzac. Until now, at any rate, for Carolyn Holbrook’s admirable Anzac: The Unauthorised Biography, provides a valuable overview of the life of the Anzac Legend from its origins up to the present. It is perhaps less ambitious in its scope than the term ‘biography’ might imply, being essentially a series of connected essays concerning what some historians, novelists and politicians have done with Anzac. There is little on Anzac Day itself, or on the popular culture of Anzac, art, music, education, or commerce, although the book does commence with a brief discussion of the egregious exploitation of Anzac by a prominent beer company – a matter taken up at greater length in James Brown’s Anzac’s Long Shadow: The Cost of Our National Obsession.

But what the book does, it does well. There is an early chapter explaining why the Boer War did not form the basis of the kind of national legend that later emerged from Gallipoli. There was a lack of major battles to celebrate, relatively few Australians were directly affected by it, and the war degenerated into a sordid affair in which a British imperial bully ground a much weaker enemy into submission by burning Boer farms and locking women and children in concentration camps. But there were hints in the emotional response of Australians to certain phases of the conflict that they ‘craved the test of war that would make legitimate their claims to nationhood’ (p. 31).

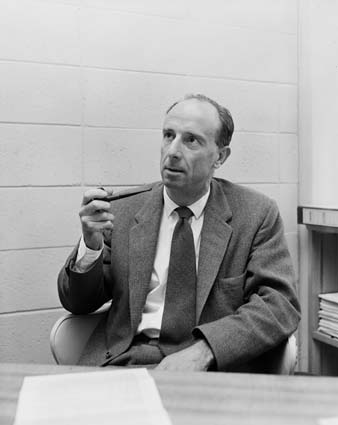

A fine chapter follows in which Holbrook compares the historical writing of Charles Bean with that of Ernest Scott, the professor of history at the University of Melbourne who wrote the domestic volume of the Official History, edited by Bean. Where Bean understood the war as having revealed the Australian racial character in a way that challenged Australia’s subservience to Britain, Scott simply saw the war as an Australian contribution to the wider imperial cause of defeating Prussian militarism. So, where Bean’s experience as a war correspondent and historian meant that he had, to an extent, ‘prised himself loose from the British embrace’ (p. 47), Scott, an English migrant, was merely confirmed in his imperial loyalism.

Holbrook also usefully shows that Bean had to work hard to remedy Scott’s sloppiness and partisanship when Bean dealt with Scott’s work in draft form. Scott had been a pioneer in the use of original sources to study the exploration of Australia before World War I but had declined into mediocrity by the 1930s as he followed his path from Fabian socialist and feminist to pillar of the Melbourne establishment and knight.

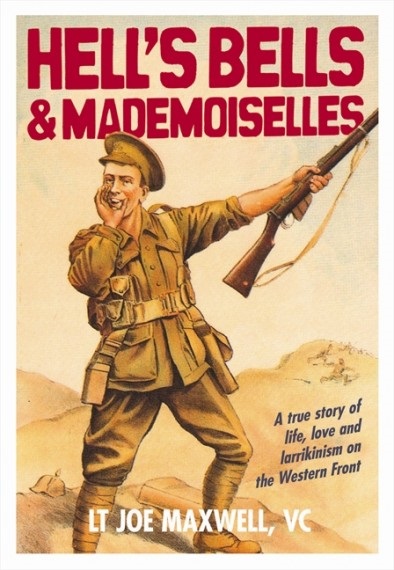

Holbrook shows that the burst of British and European war literature that occurred from around a decade after the end of the war, of which Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front was the most prominent example, did affect Australian reading habits – the books sold in large numbers – but did not have much impact on Australian war literature itself. Still, Holbrook is surely right to point out that Australian books such as Joe Maxwell’s Hell’s Bells and Mademoiselles, HR Williams’s The Gallant Company and GD Mitchell’s Backs to the Wall were by no means crude celebrations of military heroism in the vein of WH Fitchett’s pre-war Deeds that Won the Empire.

These books did not boast of the protagonists’ victories over the Turks or Germans (even if they did tend to boast about their victories over the women of Britain and France while they were on leave) and they did not imagine that the nation ‘was born at Gallipoli’ (p. 89). Yet neither were they the type of modernist war literature that was by then appearing in Britain and Europe, and which stern critics such as Nettie Palmer thought Australians should be writing.

When an Australian author did write a novel that contained sufficient literary sophistication and psychological depth to satisfy Melbourne’s chattering classes – Leonard Mann’s Flesh in Armour – the punters shunned it. Australian war novels did usually assert the worth of Australian manhood; they had that much in common with Bean. And while Australian readers apparently liked some of the modernist-influenced writing on the war coming out of Europe, they did not want such books from their own returned men. For Australians, the war could not be presented as meaningless; it had revealed the nation’s worth to the world, through the manly exploits of its troops.

It is a real strength of this book that it is sensitive to the different varieties of nationalism that have come into play in representing the war. The chapter on the radical nationalist historians of the mid-20th century – Brian Fitzpatrick, Russel Ward, Ian Turner (born in East Malvern, not Nhill as suggested by Holbrook) and Geoffrey Serle – is a sensitive discussion of the ambivalence these historians felt towards Anzac and the Great War’s legacy. Ward, in particular, in his classic work The Australian Legend, accepted Bean’s claims concerning the influence of rural values on the First Australian Imperial Force (AIF) and did his best to show that the convicts, bushrangers, pastoral workers and gold miners of the 19th century had morphed into the Anzacs and Diggers of the 20th, in their common attachment to mateship, anti-authoritarianism and a range of other ‘typically Australian’ traits.

But the problem faced by Ward, Turner, Serle and others, who were socialists or communists, and who saw bush mateship as a proto-socialism, was that Anzac acquired a reputation as a conservative legend; the political Right seemed to have a stronger grasp on it than the Left. In the end, these historians could not help but be disappointed by Anzac and it took a slightly younger historian, Ken Inglis, to raise a fresh set of questions about the topic – questions that were disconnected from the particular ideological concerns of the radical nationalists.

Holbrook sees age differences as important here. Ward, Turner and Serle all had World War II service and saw World War I as ‘their fathers’, brothers’ and uncles’ war’. Inglis was too young to serve in World War II, his father too old to fight in World War I. ‘In Ken Inglis’, she suggests, ‘the war had begun its transition from personal experience to memory’ (p. 112).

My own feeling is that this explanation, although ingenious, is not fully convincing. Inglis had been involved at the University of Melbourne in the Student Christian Movement and his whole approach to Anzac since the 1960s has been shaped by his long-standing interest in the place of religious values and rituals in public culture. The old Left had, at best, a limited interest in these matters and, following Russel Ward’s argument concerning the noble bushman’s religious scepticism and anti-clericalism, tended to treat Australia as an essentially secular society. If I have a general criticism of Holbrook’s treatment of Anzac, it would be this tendency to underplay religion, spirituality and sacredness in her account of the life of Anzac.

In the final three chapters of the book, Holbrook traces the fall and rise of Anzac since the mid-1960s. After sketching the changes in Australian society and its place in the world that undermined the Anzac Legend’s cultural ascendancy in the 1960s and 1970s, she goes on to discuss some of the individuals and forces that have produced the Anzac revival.

Holbrook suggests that the historical work of Inglis and Bill Gammage was influential in reviving interest in World War I and she also gives some weight to Lloyd Robson’s writing on the 1st AIF and Patsy Adam-Smith’s The Anzacs. She rightly credits the impact Peter Weir’s film Gallipoli – for which Gammage was an historical adviser – but not, interestingly, the television series 1915 or Anzacs. These seem to me significant omissions, but not as significant as the failure to mention either the book or the television series of Albert Facey’s immensely popular memoir, A Fortunate Life.

Geoffrey Serle 1964 (National Archives of Australia, A1200, 30709048)

At times, I wondered if, as an academically-trained historian, Holbrook was giving too much weight to the influence of other academically-trained historians, rather than looking more closely and systematically at just how Australians were becoming acquainted with Anzac in the 1980s. What was the influence of Eric Bogle’s And the Band Played Waltzing Matilda, first performed by Bogle in 1971 but only released as a recording for the first time, sung by John Currie, in the year following Gammage’s The Broken Years?

By the 1980s Anzac had, perhaps through Weir’s film especially, taken on a somewhat anti-British cast which had resonance in a post-imperial Australia. But Holbrook reminds us that this was not entirely new: ‘Australian war memory had always had an anti-British strain’ (p. 139). What was perhaps more novel – although, again, surely prefigured earlier – was the increasing emphasis on war trauma in Anzac memory, which formed a powerful alliance with nationalism to retool Anzac for our own times.

This argument about the importance of war trauma has recently been pursued in the journal History Australia by Christina Twomey at greater length than Holbrook has the space to manage here but it is a strain throughout her study of (mainly amateur) family histories of Anzac. For these family historians who often publish letters and diaries left languishing in drawers and attics for years, studying the life of a parent or ancestor is part of a process of personal discovery, as well as an opportunity to learn more about the war. Through studying their Anzacs, they believe they also learn about themselves, about who they are and where they have come from. (On this, see the remark of McGirr. HH)

The final chapter is one of the best. Based partly on interviews with former prime ministers, Holbrook shows that it is only in recent decades that the prime minister has become mourner-in-chief. There is suggested in this observation a complex recent history of political leadership and the emotions that might be further excavated. How has the revival of Anzac and the shape of Anzac memory influenced the ritual performance of prime ministerial office? How have prime ministers, in turn, shaped memory and ritual? (There are a number of prime ministerial speeches on Anzac on this website, which are accessible via the Search function. HH)

Holbrook, building on earlier work by James Curran, has certainly helped lay solid foundations for more research of this kind, suggesting that the 75th anniversary pilgrimage led by Bob Hawke was a critical turning point in the political involvement of historians in war commemoration (as well as in modern Anzac Day pilgrimage to Gallipoli, but that is a story largely beyond the scope of Holbrook’s study). Paul Keating continued the involvement, although trying, unsuccessfully, to recast Anzac as a legend focused on Kokoda and the defence of Australia in the Second World War. John Howard shifted Anzac back to a Great War focus and successfully reclaimed its cult of mateship for the conservative side of politics.

Holbrook uncovers quite a lot of new material here, and it is valuable. The 1999 addition of Kipling’s ‘Known unto God’ to the tomb of the Unknown Soldier in the Australian War Memorial, at the instigation of Geoffrey Blainey, then a member of the War Memorial Council, is a little known – and minor, yet revealing – episode in the history wars. Most of us with this kind of a bee in our bonnets about adding Christian symbolism to a grave in the resolutely classical and secular Australian War Memorial would get a peremptory brush-off, but not Blainey, and certainly not Blainey in the Howard era. Brendan Nelson apparently wanted to remove the reference and replace it with Paul Keating’s phrase from his celebrated 1993 speech at the unveiling: ‘He is all of them. And he is one of us.’ That move was recently scuttled, but Keating’s words have at least been added.

Holbrook concludes by suggesting that ‘it is time to separate myth from history: the Great War was a devastating event in which young Australians fought for the interests of a nation that was born on 1 January 1901’ (p. 217). This seems to me a part of what historians should be expected to do, but my sense is that myth-busting is unlikely to have much impact on Anzac’s place in Australian culture for the foreseeable future.

Boys lined up, Anzac Day march, Sydney, 1938 (Australian War Memorial H17131)

Boys lined up, Anzac Day march, Sydney, 1938 (Australian War Memorial H17131)

Anzac, Holbrook argues in her conclusion, needs to be understood in the context of the changing dilemmas of Australian nationalism over the course of the last century. But it is also a quest for a creed, language and liturgy which might answer a post-secular society’s need for a sense of sacred nationhood. Anzac, lending itself to a rhetoric of suffering, sacrifice and death, has been able to answer this metaphysical need in a way that Federation cannot, and never will. How, otherwise, could we plumb how or why Julia Gillard, an atheist, explains her visit to Gallipoli for the Anzac Day ceremony in the following terms: ‘I have never had the opportunity to mark Anzac Day on that sacred soil’ (p. 204).

The historians, I suspect, will continue to do their thing – hopefully, more often than not, as well as Holbrook does it here. The Anzac believers, meanwhile, will chart their own course, under the firm guidance of their priests, pastors, rabbis, mullahs and theologians.

Frank Bongiorno teaches history at the Australian National University and is currently working on a history of Australia, 1983-1991.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.