David Faber*

‘Anzac Day, Gallipoli and the Great War: a futurological retrospective’, Honest History, 7 May 2015

Why are we liable/to die for survival?/Why is our nation/fighting? Mick Hucknell, ‘Simply Red’, 2011

The end of the soldier is not, as is sometimes falsely said, to die for his country; it is to kill for his country. JA Hobson 1902

History teaches, but it has no students. Antonio Gramsci 1921

The historian’s rightful task is to distil experience as a medicinal warning for future generations, not to distil a drug. Having fulfilled this task to the best of his ability, and honesty, he has fulfilled his purpose. He would be a rash optimist if he believed that the next generation would trouble to absorb the warning. History at least teaches the historian a lesson. BH Liddell Hart 1930

History is a story. Not a very nice story, but better than no story at all. Aunty Jack

________________________

Preamble

I think an historian owes an audience a brief account of where the historian is coming from, an anticipation of his perspective. My first engagement with what CEW Bean christened ‘the Anzac tradition’ came when I was a child of about six, when a Liberal-voting uncle, nicknamed ‘Digger’, knowing that I was interested in history, put into my hands an old comic book treatment of the Gallipoli story.

That comic was my Iliad. I was amazed to think that my own people, the Australians, had been involved in such world historical events. Like the classical Greek poem, the comic taught me that war was terrible and fascinatingly dramatic. By the age of eight I was nonetheless enlisted in my father and grandmother’s opposition to the war then raging in Vietnam, to which a cousin of mine was conscripted. My grandmother had also inherited a scepticism about the Boer War, which makes me a fourth generation peacenik.

I think that peace is almost always the best option, although I acknowledge exceptions like the American Civil War against slavery, the Spanish Civil War and World War II against fascism, and certain national liberation struggles. But war to me always seems traumatic and not to be lightly engaged in. Professor Tim Takaro, Canadian health scientist and student of ‘the war on terror’, has stated ‘the human cost of war makes war untenable in modern society and we should figure out better ways to solve our problems’.[1] Difficulty is, this was already a common belief in early twentieth century, liberal Europe, yet political considerations still saw the Great War break out.

1915 and all that

In the era before that war, vested strategic and commercial interests, such as those behind the Dreadnought naval arms race between imperial Britain and Germany for control of the high seas and thus the world, profited from state investment in expansion and military preparedness. This burdened the taxpayer and stifled social programs fiscally. State funding of the arms industry as a vested interest in imperialism, itself a dynamic of overseas collocation of capital, was denounced by the progressive social liberal economist, JA Hobson, in his pre-war classic Imperialism. This analysis was developed further by Rosa Luxemburg in her 1913 work, The Accumulation of Capital, and was taken up Lenin in his wartime Imperialism: the Final Stage of Capitalism.

Potsdamer Brucke, Berlin, c. 1900 (Wikimedia Commons/W Titzenthaler)

Potsdamer Brucke, Berlin, c. 1900 (Wikimedia Commons/W Titzenthaler)

Turn-of-the-century Europe was half in love with the idea of a salutary bloodletting to dispel the ‘stagnation’ of peace. Young socialists like Mussolini and Gramsci thought war would revolutionise bourgeois society and so they welcomed it. Gramsci quickly repented of this aberration; Mussolini went on to accept French money for Allied propaganda in favour of Italian intervention in the war, becoming an anti-socialist fascist out of pique at his expulsion from the Socialist Party.

Is our era so very much different as to be able to afford complacency? As Hugh White argued in Adelaide in August 2014, the global strategic situation exhibits disturbing similarities of chauvinism and brinkmanship, for example, between the United States and China in the South Seas, with neoliberal and neoconservative hawks calling for a clash of civilisations with Iran and the entire Islamic world. One of the tests of historical significance is contemporary relevance: does a past experience resonate with present concerns and future implications? By this test the Gallipoli episode of the Great War is disturbingly significant.

‘It is sweet and seemly to die for one’s country.’ This saying was a classical expression of Roman official culture which was bequeathed to the British Empire, of which Australia was a constitutional dominion in 1914. Accordingly, Australia had no legal right to stay out of the war.

During the Great War of industrial death Horace’s happy thought was denounced as ‘the old lie’ by that most modernist of poets, Wilfred Owen, who died in battle on the very eve of the Armistice in 1918. Despite Owen, the words were still being celebrated in Adelaide – in Latin as Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori – in 1919, the year of the Versailles Conference for a ‘peace to end all peace’, when the victor of Jutland’s wife, Viscountess Jellicoe, unveiled the Commissioner of Public Works’ Honour Board in the Torrens Building in Victoria Square on 27 May.[2]

Earlier, when the first casualty reports came through from Gallipoli in May 1915, the nationalist historian Ernest Scott records in his Australia During the War that they ‘had thrown into mourning homes in all parts of the country’. Personal grief had been the wages of the Australian government’s hasty offer of an expeditionary force for service anywhere under imperial command, an offer made in the days immediately preceding the fateful and agonised decision of the metropolitan liberal Asquith Cabinet to intervene in the July Crisis in support of beleaguered France against Germany, as Douglas Newton shows.[3]

Trooper CW Collins, 9th Light Horse, Wanbi, SA, killed Gallipoli, 29 November 1915, aged 27 (Australian War Memorial P07160.001)

Trooper CW Collins, 9th Light Horse, Wanbi, SA, killed Gallipoli, 29 November 1915, aged 27 (Australian War Memorial P07160.001)

Newton’s book is an implicit historical case for war powers reform, as called for by the Greens, to give Parliament a voice in the declaration of war, which in this country is still, as in 1914, a prime ministerial prerogative liable to be exercised with little if any consultation. Newton pays tribute, as author of the tragic view of the Anzac tradition, to one of my mentors, Bill Gammage, who taught me that war can be approached empathetically and humanistically, without jingoism. This is the approach I take as a subscriber to the Honest History school of national historians. It is politically pointless to confuse jingoism with the Anzac tradition. This merely hands it over wholesale to the jingoes.

Ethical rejection of militarism must go hand in hand with appreciation of the place of the Anzac tradition in popular culture; otherwise we court rejection as a mere radical fringe. To constructively criticise, one must first seek to understand. Negative criticism of the tragic version of war from the point of view of ethical absolutes – as a victimist response to universal soldiering – simply doesn’t cut the mustard, since nothing human is alien to the true historian and warfare is endemic to humanity. Nor, by contrast, does the sarcastic dismissal of ‘the poet’s view’ of the Great War, as one British historian has stigmatised it. This rationalises the loss of a generation as the acceptable price of liberal democratic ‘freedom’ over ‘Prussian militarism’. The poet’s view is, after all, the human point of view of the individual as such, for whom war is absurd personal immolation. Only from the community point of view can war be understood and sceptically rationalised.

To return to events a century ago, by Wattle Day, 7 September 1915, when the men were still on the Dardanelles peninsula, the Governor-General was in Adelaide, inaugurating the nation’s first Anzac cenotaph. The imperial pro-consul Munro Ferguson, a failed Scottish liberal imperialist politician responsible for integrating the King’s Australian Dominion into the imperial war effort, was an enthusiastic recruitment officer and a patron of Prime Minister Billy Hughes, a Labor defence hawk from way back before the war.

The cenotaph was commissioned by the Wattle Day League, a ladies auxiliary of the Australian Natives Association, a white nativist nationalist outfit catering to middle class, white, Australian-born British subjects. It was built by Walter Torode, who also built the Stock Exchange and Elder Conservatorium and was a developer in the hills and southern parkside suburbs. The original intention was to mount this human scale monument with a stand of bronze rifles, a device subsequently employed at Salisbury and elsewhere. But Torode and the ladies thought better of doing something which might appear militaristic when peace returned. So they decided to crown the tableau of the obelisk with a bowl of flowers and the light of the Southern Cross. The monument now stands near the intersection of South and West Terraces, surmounted from circa 1935 by a bulky stone cross.

It can be seen then that Anzac Day has, from the first, featured competing tendencies between militarism and rites of public grieving, the latter owed by officialdom to those who accept the invitation to military service, arguably the most ancient and extreme form of community service. From the first, commemoration has been seen as a duty owed by the public to the community and its military volunteers and conscripts.

The authorities have had from the first to be circumspect about the recruiting function of Anzac Day. Hence the routine observation that Anzac Day is not about the glorification of war but the appreciation of service and sacrifice. There is some truth in this. There ought to be more.

Men of the 1st Battalion making wooden latrines (‘thunderboxes’), Gallipoli, August 1915 (Australian War Memorial C019121)

Men of the 1st Battalion making wooden latrines (‘thunderboxes’), Gallipoli, August 1915 (Australian War Memorial C019121)

The Anzac story needs to be told as a cautionary tale, not one of martial glory. Battlefields are filthy places. It’s not just a matter of the corpses. In the absence of a proper latrine system, tea chests were used on Gallipoli. The place smelt of faeces. During the summer, fat flies congregated on food. Eighty percent of the Anzacs had dysentery; not a lot of dignity and glory in that. One of them, Trooper Ion Idriess of the 5th Light Horse, commented in a letter, in which he described the swarms of flies, that ‘of all the bastards of places, this is the greatest bastard in the world’.[4]

Understanding this first wave of Australian war grief and its successive iterations in the century of total war – which the Marxist Hobsbawm rightly christened ‘the Age of Extremes’, 1914-91 – is essential to understanding popular and official culture in this country, Australia. Accordingly, the cultural left cannot afford not to have a voice in the commemoration of Anzac Day. This is a process which may be said to have begun with the publication decades ago of Bill Gammage’s classic evocation of the Australian soldier’s experience of the Great War, The Broken Years, and came to a certain maturity with publication a few years ago of Reynolds and Lake’s What’s Wrong with Anzac? the Militarisation of Australian History.

There are many queries which must be addressed. For example, Anglophone secondary commentaries rarely mention that a French division of Foreign Legion, Arab and Senegalese troops served on Gallipoli and, when reinforced by a second division, outnumbered the Australians on the peninsula.[5] The fact is never mentioned here. [Though note this. HH] And why is it, as visiting British historian Hew Strachan has recently noted on the ABC’s Q and A, that the emphasis is traditionally on the sideshow of Anzac, when the Australians went on to participate with tragic distinction in the main game on the Western Front, spearheading the final successful push against the Hindenburg line under Monash, a Jewish civil engineer from Melbourne? One historical reason was the relief felt at the time at the ‘successful’ blooding of settler colonial troops. The British race had evidently not degenerated in the colonies, but emerged from antipodean acclimatisation serviceable, virile and manly.

The guns of August

Why is the Great War ‘the turning point in modern history’, the ‘great catastrophe’ of the twentieth century, from which all tribulations sprang,[6] the war to end all peace? How was it that imperial Europe, in the springtime of capitalism and currency stability known lovingly as la belle époque, came to unleash its firepower and manpower upon itself, precipitating what The Economist described days into the war in August 1914 as ‘perhaps the greatest tragedy of human history’,[7] which an obscure Italian priest called ‘the Great European War’,[8] which saw 65 million troops mobilised and all quarters of the globe invested?[9] How did a schoolboy assassination in Sarajevo cause so little and precipitate so much? And how did the trauma of industrial and trench warfare, anticipated during the American Civil War, come to irreversibly fix in the popular mind the bloody cost of war for generations?

Because, of course, as in Australia, the great bulk of a generation of military age were mobilised. Because more than 20 million soldiers and civilians perished and another 21 million were wounded and upwards of 20 million died of the global influenza pandemic of 1918-19.[10] Why did this outbreak of insanity lead to Australian participation in the greatest amphibious operation in history to that time, the invasion of European Turkey? These are the questions we must answer to understand Gallipoli and the birth of the Anzac tradition.

The Europe of 1914 was an imperial continent which may be said, with a grain of salt, to have been divided into two armed camps. In the Age of Imperialism, the phenomenon was not without its earnest critics, like the economist and progressive liberal social critic, John Hobson, mentioned above, but the critics were in a minority in the days of Rider Haggard and King Solomon’s Mines, which was a bestseller with 5000 copies purchased in two months in 1885.[11]

Brick mission building, Belgian Congo, c. 1900-15 (Wikimedia Commons)

Brick mission building, Belgian Congo, c. 1900-15 (Wikimedia Commons)

Even ‘little Belgium’, invaded by Germany in August 1914, was an African imperial power of particular ferocity in the Congo, as was well known but conveniently forgotten by the jingoistic press at the time.[12] The roots of this system of alliances, which eventually split the diplomatic Concert of Europe, went back half a century to the unifications of two nations, Germany and Italy, over the ashes of the French Second Empire and the socialistic Commune of Paris of 1871.

If these defensive alliances, with their escape clauses in case of aggressive war were not absolute straight-jackets, still they were designed to stabilise matters and they involved rigidity. Liberal ‘democratic’ France and autocratic Russia were bonded in an entente or ‘understanding’, later (1904) involving Britain. This was a matter to Germany’s great concern, threatening it with a war on two fronts in Central Europe, and which it countered with an alliance involving Austria-Hungary and Italy.

That Germany was overtaking Britain economically and industrially and challenging her naval supremacy only heightened the sense of existential threat, triggering a first response psychosis in both countries and with the allies France and Russia. So, while the German General Staff under von Schlieffen plotted to invade North-western France through the Low Countries and take Paris before the Russian steamroller over-ran Prussia, a resurgent France plotted to invade Germany by way of retaking Alsace and Lorraine, which it had lost in 1871.

It should be remembered that the anti-semitic Dreyfus Affair (1894-1906), which divided and radicalised the Third Republic, centred on the leaking of French plans to the Germans. There was plenty of paranoia to go round. Germany’s continental empire was matching the far-flung British Empire demographically and was gaining on Great Britain in economic power and military potential.

In 1883, at the height of the Age of Imperialism, Britain had a 37.1 per cent share of world trade in manufactures. By 1913 this had slid to 25.4 per cent. In the same period Germany’s share rose from 17.2 to 23 per cent. This was all part and parcel of the normal processes of capitalist development but it did nothing for British confidence in the future.[13] Economic competition and the arms race went hand in hand. British fear of German continental hegemony and Germany’s regressive tax base, unfitted to sustaining military expenditure, tipped both towards war sooner rather than later.[14] It is ironic, not to say tragic given Germany’s current patronage of austerity, that she now enjoys the predominance Britain fought two world wars to forestall. Was it all worth the immolation of a generation to deprive Germany of its natural weight in Europe?

Belle époque Europe was ‘civilised’, industrialising and urbanising at an unprecedented rate, but, as Keynes was to comment, the veneer was to prove skin deep, the confidence complacent. It was a time of schemes of arbitration between nations and even international governance. It was a hierarchical class society of monarchies and parliaments, with the aristocracy still ensconced in the military, society and the state. As one recent historian has commented, this worst and best of times was not unlike our own, globalising and with expectations of peace persisting long term, but wracked towards its end by international crises.[15]

These were the years of the birth of mass literacy and the nationalist mass media, which just goes to show that a little knowledge is a dangerous thing. Cities were insalubrious, working hours were long and conditions hard. In liberal parliamentary Britain and Italy for example, troops were regularly called out to quell industrial and rural unrest. In Italy there were nationwide agrarian and bread riots and a monarchical military quasi-coup in the commercial capital of Milan in 1898. There was an anarcho-socialist uprising in Barcelona in 1909, provoked by colonial warfare. These were years of cultural irrationalism, when Freud analysed the sewers of the soul and the French engineer turned ‘syndicalist’ and later fascist sympathiser George Sorel, in his Reflections on Violence, irresponsibly theorised worker rebellion in uproar motivated by myth.

John Buchan, 1915 (Wikimedia Commons)

John Buchan, 1915 (Wikimedia Commons)

The new century opened with the British Empire mired in an expansionary colonial war in South Africa, when Churchill and Baden-Powell accomplished feats of derring-do, in emulation of the imperialist public schoolboy adventure novels of JA Henty and the Scot, John Buchan, once of the imperialist Lord Milner’s South African ‘kindergarten’ and subsequently author of the 1915 espionage propaganda novel The Thirty-nine Steps.[16]

Henty in particular flourished at the time of the late nineteenth century public schools movement, when team sports were all the rage, viewed as paramilitary exercises, rather than, as the late great Bill Shankley of Liverpool FC fame was to describe them, as ‘socialism without the politics’. It was this sort of ‘boys’ own’ literature, wherein the middle class subaltern typically won his spurs and earned the respect of his aristocratic superior, that made the young TE Lawrence (immortalised during the Great War, between the wars and during World War II as ‘Lawrence of Arabia’ by a wartime media eager to celebrate gallant political warfare which was not mired in the mud and stagnation of the trenches) want to grow up as an imperial hero.[17]

It was no accident that the tabloid press whipped the populace up to war hysteria upon the relief of Mafeking during the Second Boer War (16 May 1900), occasioning a doggerel ode by the worst poet in the English language, William McGonagall (famously mock-revived by Spike Milligan and The Goons), despite Liberal Opposition Leader Campbell-Bannerman’s pacifism in the House of Commons.

In 1914 there was another anarcho-syndicalist uprising, this time in Italy, known as Red Week. It came in protest at the liberal nationalist right turn of the Giolitti government, which weakened the Ottoman Empire, for two centuries considered ‘the sick man of Europe’, by invading Libya in 1911. (This was an adventure bitterly opposed by the Socialist Party and others but supported by the Catholic Church.)

Again in 1914, Ulster was on the brink of civil war, when military officers at The Curragh mutinied rather than enforce Home Rule against Loyalist paramilitaries in a rebellion connived at by the Conservative Party and the House of Lords. This was at the time when suffragettes were being force-fed by Home Secretary Churchill and Asquith was reluctant to extend the vote to women. All of these things, taken together, occasioned what historian George Dangerfield called ‘the strange death of liberal England’, corrupt, bedraggled and unmourned.[18]

Meanwhile, in Berlin the Imperial Diet was like the Russian Duma, only consultative. Russia, of course, had been weakened by war and revolution in 1905. Bestsellers around Europe began to presage a conflagration and talk of espionage and invasion: bellicose straws in the wind.

In Australia before the Great War the same ‘boys’ own’ imperial literature as infected metropolitan Britain flourished in a context of militarisation of education and social and political preparation for national and imperial defence. In 1905, in keeping with the theory of the democratic nation in arms pioneered by the revolutionary Jacobin liberal French Republic, the liberal-conservative Deakin ‘Fusion’ Government brought in universal compulsory cadet training for boys aged 12-14 and for youths aged 18-20.

This scheme was known and widely detested as ‘boy conscription’ and it lasted until 1909. Then, on New Year’s Day 1911, a Labor government brought in compulsory military training for males aged 12-26. This ‘universal’ system was widely evaded. Of the 350 000 boys aged 10-17 liable for training in 1915, about half never registered or were exempted.[19]

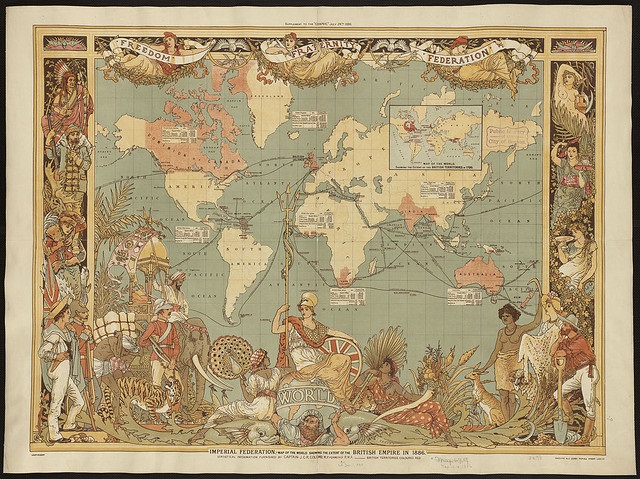

Map of the world showing the extent of the British Empire in 1886 (Wikimedia Commons/JCR Colomb)

Map of the world showing the extent of the British Empire in 1886 (Wikimedia Commons/JCR Colomb)

From 1900 to 1930, to say nothing of the colonial era,[20] early twentieth century Australian culture was saturated with British imperial propaganda, especially in our schools.[21] It was a time of saluting the flag at assemblies and Empire Days, when pupils, in the words of one woman of the interwar generation ‘got the British Empire for breakfast, dinner and tea, morning, noon and night’.[22]

If not all Australians were taken in, still many were brainwashed. A scholar of the Vietnam generation, Patsy Adam Smith, recalls that many veterans of the Anzac generation were so indoctrinated that volunteering, as they did en masse, was an expression of second nature which they could not rightly rationalise. It was very much a case of ‘a man’s gotta do what a man’s gotta do’.

As the casualties of the Great War mounted, and the divisive conscription referenda of 1916 and 1917 came on, the militarisation of childhood in Victorian primary schools faltered.[23] But as late as the Vietnam years I recall a playground conversation at Somerset Primary School in Tasmania about the relative liabilities of being a boy or a girl. Girls it was agreed ‘had’ to endure childbirth, but boys ‘had’ to go to war. I had a cousin conscripted to Vietnam at the time.

Gallipoli

With North-western France occupied and the Germans dug in outside Paris, British statesmen and grand strategists looked East to unlock the deadlock. For Britain as a naval power the question was how to bring the Royal Navy into play as a strategic factor. An earlier plan to turn the Western Front by landing in Danish Schleswig or on Germany’s Baltic coast was discarded. The Gallipoli project, reviving long discarded designs, began as ‘a brilliant idea’ in the fertile brain of First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill. (Professor Robin Prior considers very plausibly nevertheless that Prime Minister Asquith was the real culprit for chairing a War Council which approved an airy grand design to take Constantinople without proper scrutiny. Married to society political hostess, Margaret Asquith, who had some charming views about colonials, Asquith had his mind on an affair with one of his daughter’s girlfriends.)

Churchill, a lineal descendant of Queen Anne’s field marshal, John Churchill, first Duke of Marlborough, was, however, the Minister who got the wind beneath his wings about the Dardanelles proposition. Like his illustrious ancestor, whom ‘Winnie’ devoutly admired and wrote about, the First Lord was frankly manic depressive. Collaborators and admirers knew him as an ideas man whose judgement was periodically alternately brilliant and faulty, due to his cyclothymic manic-depression.[24]

John Churchill, First Duke of Marlborough (Flickr Commons)

John Churchill, First Duke of Marlborough (Flickr Commons)

The D-Day Mulberry harbours which so facilitated the amphibious invasion of Normandy in 1944 turned out to be one of Churchill’s better ideas. (FDR said, ‘He has a hundred [ideas] a day and about four of them are good’.)[25] Gallipoli was not one of his good ideas. Typically, it was overblown. The Russians had requested in late 1914 a diversion to relieve pressure on the Eastern Front, but not the winning of the war by the capture of Istanbul by their allies, the Russians having laid claim to the Straits themselves.[26]

Churchill, on the other hand, not only envisaged keeping the Russians in the war by opening up a better supply route to them, but widening the route to encourage Bulgaria, Greece and Italy into the war to attack the Habsburg forces from the South-west and South,[27]thus deepening Germany’s two front dilemma. Indeed, the Gallipoli enterprise, in seeking to resolve the historic Eastern Question and knock the Ottomans out of the war with one blow, dismembering their empire to Britain’s advantage and Germany’s detriment, represented an escalation of the war in a search of a military solution.

It would have been better if the Great Powers, having mauled and stalemated one another in Flanders fields to the tune of a million dead, had taken their cue from the Hague Conference which founded what became the Women’s International League For Peace and Freedom. The conference opened three days after the Gallipoli landing and sought a negotiated truce with a view to an enduring peace.[28] Had the combatants taken this line, they could, at the very least, have fought another war (if they were so inclined) with a clearer understanding of what modern armed conflict was like.

Instead, a generation was sacrificed to a world war which, when it ended, gave rise, as Marshal Foch predicted, to another war within a generation. And gave rise to an unjust and unstable Middle East with which we are still politically and militarily embroiled on prime ministerial initiative unfettered by any parliamentary declaration of war.

* Dr David Faber, a Tasmanian-born historian, was a Visiting Research Fellow at the University of Adelaide, 2011-14.

[1] See Shawn Conner, ‘”Human cost” of war on terror must be considered: SFU prof’, Vancouver Sun, 25 March 2015, reporting Simon Fraser University report on casualties in Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan Body Count, released March 2015.

[2] The direct quote is by the soldier-scholar Arhibald Wavell. It is cited as the keynote to David Fromkin, The Peace to End All Peace: Creating the Modern Middle East 1914-22, Henry Holt and Co, New York, 1989.

[3] For a masterful discussion of Australia’s rush into the Great War, see Douglas Newton’s recent study Hell-Bent: Australia’s Leap into the Great War, Scribe, Brunswick, 2014, endorsed by doyen Henry Reynolds as an ‘instant classic’ of Australian historiography.

[4] Cited on the back cover of Gallipoli 1915, ABC Books/Commonwealth Dept of Veterans Affairs, 2002.

[5] Matthew Hughes, ‘The French Army at Gallipoli’, Royal United Services Institute Journal, June 2005.

[6] David Fromkin, Europe’s Last Summer: Why the World Went to War in 1914, Vintage, London, 2004, pp. 5-6.

[7] Ibid., p. 5.

[8] Don Antonio Cattalan, Libro Chronistorico San Vito de Leguzzano.

[9] Fromkin, Europe’s Last Summer, p. 5.

[10] Ibid.

[11] AP Thornton, The Imperial Idea and its Enemies: a Study in British Power Papermac, London 1959, 1966, p. 93n.

[12] For the exposé on ‘Leopold’s Congo’ by the Anglo-Irish British imperial civil servant Roger Casement on behalf of the ‘international community’ of the late 19th century, see Part I of Brian Inglis, Roger Casement, Coronet, London, 1973, 1974. Casement was, of course, hung for treason by the Empire he had served after he was convicted for running German rifles to Irish nationalists during the Great War.

[13] Richard Shannon, The Crisis of Imperialism 1865-1915, Granada, London, 1974, 1976. p. 12.

[14] On this implication of Wilhelmine Germany’s fiscal woes, see Fromkin, Europe’s Last Summer, p. 93.

[15] Ibid., pp. 4, 11.

[16] Re Buchan and Henty, see Thornton, op. cit., pp. 92-94

[17] For WWII publications about Lawrence see: the concise edition of Lawrence and the Arabs, Longmans, Green & Co, London & New York, 1940, by his friend the poet and autobiographer Robert Graves; HI Shumway, War in the Desert, Collins, Glasgow, 1940, 19145. For Lawrence’s own semi-fictional account of his war, see Seven Pillars of Wisdom, Penguin, 1926, 1981, characteristically praised by Churchill and Buchan as military adventure writing. For three biographies of Lawrence see: Richard Aldington, Lawrence of Arabia, Penguin, London, 1955, 1971; Desmond Stewart, TE Lawrence, Granada, London, 1977, 1979; Michael Yardley, Backing into the Limelight, Harrap, London, 1985, 1986.

[18] See The Strange Death of Liberal England, Paladin, London, 1935, 1966.

[19] Wikipedia, `Conscription in Australia’, citing the standard work, John Barrett, Falling In: Australians and “Boy Conscription’”, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney 1979.

[20] For a seminal study of the connection between British Imperialism and Australian Nationalism: Manipulation, Conflict and Compromise in the Late 19th century, see Luke Trainor, CUP, Melbourne 1994

[21] See historian of education, Bob Bessant, ‘British imperial propaganda in Australian schools 1900-30’ in Working Papers in Australian Studies 1998, Sir Robert Menzies Centre for Australian Studies, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London. See also his ‘Schools and the State’ in Bessant and Spaull, Politics of Schooling, Pitman, Carlton, 1976.

[22] Citation from memory of an anonymous elderly woman, stated to me on a bus trip from Launceston to Hobart Tasmania in 1994.

[23] See The Anzacs,Penguin, 1978, 2014 Part I ‘The beginning’, Section 1 `Why did you go to the Great War Daddy?’ and Section 2 ‘Moulding the Lads’. The reference to the wartime repugnancy of regimenting junior cadets in Victoria is from p. 16.

[24] Goodwin and Jamison, Manic-Depressive Illness, OUP, 1990, p. 359.

[25] Cited in Nassir Ghaemi, A First-Rate Madness: Uncovering the Links Between Leadership and Mental Illness, Penguin, London, 2011, p. 61.

[26] See Shannon, Crisis of Imperialism, p. 470.

[27] Marc Ferro, The Great War 1914-18, Routledge, London & New York 1969, 1987, p. 65.

[28] On the early years of the WILPF, see Gertrude Bussey, Pioneers for Peace: WILPF 1915-65, Alden Press, Oxford 1980.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.