Kristen Alexander*

‘Captives of war make a compelling story of World War II’, Honest History, 22 October 2017

Kristen Alexander reviews Clare Makepeace’s Captives of War: British Prisoners of War in Europe in the Second World War

Clare Makepeace’s grandfather was one of the 10 000 or so men of the 51st Highland Division, captured at Valéry-en-Caux, in the Normandy region of northern France, on 12 June 1940. Like many former prisoners of war, Andrew Makepeace rarely spoke of his experiences of captivity. From a young age, his granddaughter realised his silence concealed something that words could not encompass and she ‘struggled to reconcile this: how could my kind, gentle, patient grandfather have gone through things so dreadful they had rendered him mute …?’ As she grew older, she and other family members questioned him, but Andrew Makepeace let slip only snippets.

During his final years, Andrew talked more and more about the war with an old friend with whom he had been called up, served, and shared captivity. But he still resisted his family’s entreaties to tell his story. His excuse for not recording his experiences was that he could not add to the many existing accounts by World War II’s ex-prisoners of Europe – and he had read many. More modestly, he claimed that, in comparison, his war would be uninteresting. His granddaughter continued to urge him to break his reticence. Then, he finally revealed the truth behind his silence: ‘Why would I record my story? … It would just be one long tale of humiliation.’

During his final years, Andrew talked more and more about the war with an old friend with whom he had been called up, served, and shared captivity. But he still resisted his family’s entreaties to tell his story. His excuse for not recording his experiences was that he could not add to the many existing accounts by World War II’s ex-prisoners of Europe – and he had read many. More modestly, he claimed that, in comparison, his war would be uninteresting. His granddaughter continued to urge him to break his reticence. Then, he finally revealed the truth behind his silence: ‘Why would I record my story? … It would just be one long tale of humiliation.’

In the face of such bitter uncommunicativeness – or early deaths – many children, grandchildren and more distant family members decide to fill the gaps. Some read around the subject as much as they can. Others write the former prisoner’s story themselves. (See, for example, the journey of discovery of the son of a prisoner of Japan.) Clare Makepeace was no different. In an attempt to understand something of her grandfather’s experiences, and to make sense of them, she turned to histories of captivity.

But rather than pen a de facto memoir or family biography, the young cultural historian took her investigation further; it became the starting point for her doctoral thesis on the ways in which British World War II prisoners of war in Europe made sense of their captivity. From urgent curiosity through to scholarly enquiry, Makepeace’s personal response to her grandfather’s incarceration resulted in a perceptive thesis (“A Pseudo-soldier’s Cross”: The Subjectivities of British Prisoners of War Held in Germany and Italy during World War II, Birkbeck, University of London, 2013).

Many early career researchers put aside their doctoral research as they survey other subjects and seek to answer different questions. Makepeace’s broad scholarly interest lies in the emotional cost of war to individuals during conflict and its aftermath, and she focuses upon the wider tropes of emotions in war and memories of conflict. So, she has not turned entirely from studying the effects of captivity and the way in which prisoners respond to them. The result is Captives of War: British Prisoners of War in Europe in the Second World War, the first cultural history of British prisoners of Germany and Italy in World War II.

It is important to note that, while this monograph may have ultimately arisen from Makepeace’s unanswered questions about her grandfather’s captivity, objectivity has not been sacrificed. Both thesis and Captives of War are meticulously researched. At all times, Makepeace demonstrates insightful interpretation, penetrating analysis and academic rigour. I must stress that Captives of War is not Makepeace’s thesis. While there are commonalities, the two works are very different. Her research continued, her thinking evolved, and there are a number of new chapters. Captives of War is a much more profound, complex and mature work than the thesis.

In Captives of War, Makepeace does not seek to explain wartime imprisonment and what the men did during their years of confinement. That has been done before, and in great detail. (In the Australian context, for instance, Peter Monteath’s authoritative P.O.W. comes to mind.) Rather, her central research questions revolve around how British captives responded emotionally and psychologically to internment, how they coped, how they made sense of their experience, and how they came to terms with it.

In seeking answers, Makepeace scrutinises their ‘interior and intimate worlds’ through the contents of what she collectively terms ‘personal narratives’, their wartime letters, diaries, artworks and log books. She is astute in her inferences, in interpreting the thoughts, feelings, motivations, and sensibilities behind the words of her cohort. While she is dispassionate in her analysis, the intimacy of her source material often allows her to present a poignant account of captivity.

Captives of War covers not only captivity by Germany but also by Italy. Moreover, while escaping from captivity is one of many responses to it – and is usually presented as the dominating feature of wartime incarceration, particularly in German prisoner-of-war camps – it figures only slightly in this work. Instead, Captives of War dissects the subjects the men most often turned to in their correspondence and private jottings: how they were captured, what it was like to be imprisoned servicemen, negotiating camp life, home and their eventual homecoming, and their psychological state.

By drawing on personal narratives created during captivity – and eschewing memoirs and late-life interviews as source material – Makepeace presents captivity as a lived experience. She evaluates what happened as it unfolded, rather than from polished remembrances, shaped-for-a-good-story narratives, and oral history interviews – many of which have been influenced by popular culture. The personal narratives of her cohort, even those of the men who had a specific readership in mind, are fresh, genuine and unvarnished. In many instances, they are raw and emotional.

Makepeace’s preference for contemporary evidence is also based on a noteworthy insight. She discovered that post-war reflections often look back from the perspective of knowing how long imprisonment lasted and, in doing so, focus on the monotony and boredom of an indefinite captivity. The personal narratives of her cohort, however, reveal that they did not experience captivity as something interminable. For them, incarceration was something that would end imminently – when the Allies won the war. This was not just wishful thinking or high hopes. It was something they believed very strongly.

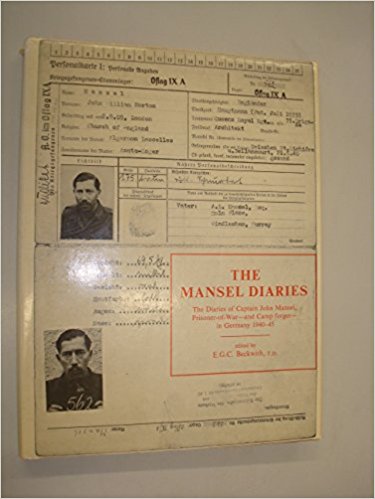

Published edition (1977) of the Mansel diaries (Amazon)

Published edition (1977) of the Mansel diaries (Amazon)

Makepeace notes that 142 319 men serving in Britain’s armed forces were captured by Germany and Italy during World War II. At least 8591 of those were Australians, identifying and registered as ‘British’ servicemen. Captives of War’s source material is rich and varied. It draws on the personal narratives of 75 British soldiers, airmen and mariners imprisoned in war in Germany and Italy. Those 75 men compiled 40 diaries, 25 wartime log books and 26 sets of letters, including the 223 letters written by merchantman Greaser Claude Bloss to his wife during the five years of his captivity, as well as the ten volumes of pocket diaries, exercise books, logbooks, and 250 letters and postcards which comprise the personal archive of Captain John Mansel.

While none of Makepeace’s cohort were Australian, they served with and were interned with Australians. Accordingly, the contents – and Makepeace’s deep analysis – of their intimate records, expose much which directly relates to the Australians, as well as to other Commonwealth and Dominion men serving with British forces.

A handful of names recur. As well as Mansel and Bloss, the reader frequently encounters Canon John King and Sergeant Major Andrew Hawarden. Accordingly, while Makepeace painstakingly establishes and competently explores the broader collective experience of captivity, the reader gains a clear sense of the individual response. In gaining access to these men’s deepest thoughts and private words, we feel we know them as personalities, not just as exemplars.

Enhancing this remarkable quantity of personal testimony is its quality. Mansel’s commentary, in particular, was perhaps the most contemplative of any of the men in Makepeace’s cohort, and revealed how he made sense of his captivity as it continued. He was also perhaps the most consistent, writing constantly in his diary. Never short of a subject, he found something of interest even on those days which had nothing much to recommend them. To the incredulous questioning of his fellows – along the lines of ‘what on earth can you write about?’ – his quiet response in the privacy of his diary was ‘that people who can find nothing of which to write have no imagination’.

Many of the cohort did fail to provide meaningful detail about life in captivity, especially in their letters home, but it was not just lack of imagination or perhaps even literary talent that stilled their pencils. Sometimes, much to the chagrin of their homefolks, as Makepeace points out, they were victims of censorship, formulaic letter constructions, and the limited space available in printed postcards and letter forms. (Makepeace provides an image of a letter form and postcards so the reader can see how little room was available to prison-camp correspondents.)

In the case of prisoners with partners at home, letter-writers were also obliged to include a certain proportion of billet doux-type content to satisfy and reassure loved ones of their continuing affection. Much space was also devoted to ensuring the writer’s continuing presence in his loved ones’ lives.

The richly varied personal testimony produced by Makepeace’s cohort is remarkable but, regardless of the quality of any source material, there are often limitations; Makepeace highlights the inadequacies of the personal narratives. For example, descriptions of capture are often fleeting and barely elaborated upon in letters. The more detailed, narratively-shaped accounts which are the province of diaries are usually written after a lengthy transit, delayed arrival in a permanent prison camp, and a period of introspection and sense-making.

Most of Makepeace’s cohort are officers, so her focus is on experiences in central facilities, rather than in often harsher work and satellite camps. This was more by accident than design, arising from the available source material. Makepeace drew the majority of her personal narratives from public archives, particularly the Imperial War Museum. Officers wrote more than half the collections of letters she consulted.

Makepeace also found that reflective diaries and log books were also more likely to be written by commissioned and senior non-commissioned officers. She posits a number of reasons for this: officers and senior NCOs were not obliged to work; better standards of education; class-related differences in attitude. Irrespective of why officers created more personal narratives, historians can only use private records which have been made available to them. If public appeals or entreaties to veterans’ associations fail to elicit collections of personal evidence, public archives are the logical place to turn.

But what happens if family record-keepers do not deposit treasured personal records with these institutions? What if they decide the records would be better kept within the family? This is a dilemma which every family record holder must resolve: in retaining personal records within family archives, stories remain untold, unexplained, and outside the collective experience.

British prisoners of war, World War II (Daily Mail)

British prisoners of war, World War II (Daily Mail)

Captives of War may be officer-centric, with little reference to the experiences of enlisted men in the work and satellite camps, but this is by no means a fault. Indeed, Makepeace soundly analyses both the personal perspective and universality of the collective experience in the 248 German and 72 Italian central prison camps, and contextualises contemporary personal narratives by official reports such as War Office records, camp histories, Red Cross reports and records, liberated POW interrogation questionnaires as well as medical diaries, reports, and contemporary psychiatric research which probe the peculiar mental challenges of captivity.

Makepeace draws many important conclusions about the nature of captivity and how men respond to it. In Chapter One, she explains the way in which the majority of her cohort were captured and concentrates on how they made sense of that event. Of particular importance for self-esteem, military pride and perception of their own masculinity was that prisoners of war showed in their narratives that they were not personally responsible for their defeat and captivity. Their regiment, for example, may have surrendered or been captured, but they had not given up the fight and had no part in their capture.

In Chapter Two, Makepeace establishes that her cohort needed to make sense of their incarceration, whether for themselves at the time, or with a particular readership in mind, such as a partner. One way they did this was by representing themselves through their wartime personal narratives as continuing to live normal lives with routines, hobbies, interests, and aspirations for the future. They recorded how they managed their days, filled their time, and notched up individual and collective achievements, such as sporting successes and well-received theatrical productions. This active time management justified the time away from combat and reinforced that they were not wasting their lives. Their catalogues of accomplishments also helped make sense of their lives and gave some meaning to them, particularly for those who planned for their post-war lives by studying.

As well as establishing a ‘normal’ life which in many ways replicated their pre-captivity lives, Makepeace’s cohort noted the strange idiosyncrasies of captivity, such as new words, camp money, food and menus. In doing so, despite continuing links to home and past lives, the men created and recorded a distinct captivity identity. Part of that identity was built around the nickname they adopted, ‘kriegie’, a contraction of the German Kriegsgefangener, ‘war prisoner’. But this identity, while indicating adaptation to and bonding within captivity, was not necessarily representative of that state. When they referred to kriegie life, it was always with humour and self-mockery; paradoxically, they both accepted and derided their kriegie existence.

Makepeace displays this dual perspective well. As well as describing determined adaptation, she exposes acts of defiance, in reality and in the privacy of their personal narratives. For example, in the post-Great Escape climate where the Germans distributed posters declaring that ‘Escaping is no longer a sport’, one naval wag responded by captioning a drawing of Popeye-the-sailor-man striding through broken barbed wire: ‘Sez who?’

Chapter Three, ‘Bonds between men’, details relationships within the crowded homosocial environment. Here, Makepeace argues that, although the men bonded on a broader level and even adopted a kriegie identity, they did not create group solidarity. As well as detailing how the men negotiated communal living, Makepeace scrutinises cross-dressing as part of a theatre culture. She also looks at female impersonators who step beyond the proscenium arch, stimulating admiration and desire and, in some instances, possibly transgressing the boundaries of male heterosexual desire. What is particularly surprising is that the contemporary personal narratives illustrate considerable understanding, tolerance and expediency towards expressions of prison-camp sexuality. (One of my favourite images is that of Stalag 383’s ‘Pinky’ Smith in full drag. So popular was this camp photograph that 14 000 orders were placed for it.)

Andrew Makepeace (far right) as a prisoner of war (Warfare Historian; an illustration in the book)

Andrew Makepeace (far right) as a prisoner of war (Warfare Historian; an illustration in the book)

Drawing on important items of material culture such as letters, photographs, and parcel contents, Chapter Four examines how the men looked homeward in order to draw emotional strength. It highlights that, in many instances, POWs experienced a changed relationship with their loved ones. As prisoners, they were no longer the head of the household, responsible for their family’s welfare. Moreover, instead of providing for their dependants, they themselves were now in positions of dependency reliant upon comfort parcels and letters from home.

Captives of War is one of the few monographs which explores neurosis in World War II incarceration. In Chapter Five, Makepeace surveys the history of prisoner of war psychology, shows how prisoners (in the parlance of the time) went ‘round the bend’, and looks at the various ways the men referred to psychological disturbances. She concludes that, while a significant minority suffered psychologically as a result of captivity, ‘little clarity and much ambiguity’ ensued, because of the lack of any firm or consistent diagnosis.

As well as covering the final months of captivity, Chapter Six looks at how the men ended their captive narratives, how and why they placed the final full stop in their personal accounts. Despite the men in many instances revealing a capture-long loquaciousness, this chapter shows the difficulties experienced in articulating feelings on release.

In Chapter Seven, Makepeace changes emphasis from captivity-created letters and diaries. Here, she studies the cohort’s return entirely through medical papers and psychiatric reports because, once liberated, her cohort ceased writing. Those reports give an important insight into homecoming and the immediate post-return years.

As with other volumes in Cambridge’s Studies in the Social and Cultural History of Modern Warfare series, Captives of War is a quality production. It is case bound, printed on ‘good’ paper, has few if any typographical errors, and contains a generous selection of 29 well-captioned images which pertinently illustrate Makepeace’s arguments.

The book’s cover illustration, a watercolour by British official war artist and prisoner of war John Worsley, is particularly evocative. With a limited palette, depicting the men trudging the snow-bound ‘circuit’, trapped by barbed wire and overlooked by a sentry tower, Worsley reveals the claustrophobic, depressing aspect of captivity. The hidden story behind the image is that it also demonstrates another mechanism of personal sense-making of captivity – art. As well, Worsley, like other captives, coped with incarceration by putting his talents at the disposal of his camp’s escape committee. He forged identity papers and constructed a life-sized mannequin which stood in for an officer during roll-call to cover up an escape. (‘Albert RN’ later starred in the eponymous film based on that escape attempt.)

Captives of War includes an extensive bibliography of primary and secondary source material and Makepeace has thoroughly substantiated her research with footnotes. There is also an excellent index. Emphasising that Makepeace has a solid foundation for her examination, Appendix Two summarises her cohort’s broad range of experience, including length of captivity, ages, marital status, and the variety of camps in which they were interned. Makepeace deftly blends academic analysis with sensitivity and, in particular, skilfully conveys complex medical and psychological terms so they are readily understandable. Captives of War is well-written and, while aimed at a scholarly audience, is accessible to more general readers.

The captivity experience does not necessarily end at release. Indeed, Michael McKernan, for one, has demonstrated in his This War Never Ends that the effects can last a lifetime. (See also McKernan’s 2015 discussion of these issues.) While Makepeace touches this aspect only lightly – as indicated above, her investigation ends shortly after liberation and homecoming – inclusion of her grandfather’s story and her response to it reflect the lifelong and intergenerational effects of captivity.

In a sense, Makepeace is representative of those who seek to fill the void of silence left by fathers, grandfathers, and uncles who did not share their experiences with their families. Through Captives of War, she provides a sense of understanding to those who do not have access to contemporary or late-life personal records because, like Andrew Makepeace, their forebears never created them and spoke only sporadically and disjointedly.

In a sense, Makepeace is representative of those who seek to fill the void of silence left by fathers, grandfathers, and uncles who did not share their experiences with their families. Through Captives of War, she provides a sense of understanding to those who do not have access to contemporary or late-life personal records because, like Andrew Makepeace, their forebears never created them and spoke only sporadically and disjointedly.

Makepeace’s enquiry is scholarly, sensitive, nuanced, and embraces paradox. She has been eminently successful in her aim to improve our knowledge of captivity as experienced by World War II’s British POWs, and, more broadly, contribute to the literature of captivity in the two world wars. Because of Australians’ membership of Britain’s forces, Captives of War is relevant to Australian prisoners of war in Europe. I have no hesitation in recommending this pioneering examination of life in captivity. It is a major work which illuminates what is known of how prisoners of war responded to, made sense of, and came to terms with their incarceration. It is also a significant contribution to the cultural history of warfare.

* Kristen Alexander is an Australian writer, author, bookseller and PhD candidate at UNSW Canberra. Her book Taking Flight, on aviator Lores Bonney, was reviewed on Honest History and she reviewed the Beyond Surrender collection on Australian POWs and Mark Baker’s Phillip Schuler.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.