John Myrtle*

‘A textbook on the early history of the Wide Brown Land’, Honest History, 19 March 2021

John Myrtle reviews A House of Commons for a Den of Thieves: Australia’s Journey from Penal Colony to Democracy, by Adam Wakeling

A House of Commons for a Den of Thieves, a chronological history of the constitutional development of Great Britain’s Australian colonies, is the latest contribution to writing on Australia’s early colonial history. It is written by Adam Wakeling and is his third published historical work, the first being The Last Fifty Miles (2016), an account of Australia’s role in decisive victories in the final stages of World War I, followed two years later by Stern Justice, the story of Australia, Japan and the Pacific war crimes trials.

Transportation of convicts to New South Wales began in 1788 and ended in 1840. The colony achieved responsible government in 1856, and its first election with both manhood suffrage and the secret ballot was held in 1859. In the words of the author, A House of Commons for a Den of Thieves is the story of how the citizens of [the Australian] colonies threw off the stigma of their criminal origins and asserted their rights’.[1]

Transportation of convicts to New South Wales began in 1788 and ended in 1840. The colony achieved responsible government in 1856, and its first election with both manhood suffrage and the secret ballot was held in 1859. In the words of the author, A House of Commons for a Den of Thieves is the story of how the citizens of [the Australian] colonies threw off the stigma of their criminal origins and asserted their rights’.[1]

At first, the book focusses on the civil institutions of Great Britain, together with the governance of New South Wales as a penal colony. In Britain, the institutions of criminal justice in the eighteenth century were crude, with no professional police force and no public prosecutors, and all felonies carried the death penalty. However, not all offenders were hanged, and with insufficient gaols, penal transportation was introduced. By the late 18th century the prison population had doubled and transportation to the American colonies was no longer an option, so in 1786 the British Tory Government of William Pitt the Younger settled on New South Wales as a penal colony, with Arthur Phillip as Governor.

The First Fleet left England on 13 May 1787 and commenced landing at Sydney Harbour on 26 January 1788, with 1030 persons going ashore, of whom 736 were convicts, including 188 women, with the rest being marines, civil officers, wives and children.[2] Norfolk Island was also occupied in 1788, with the soil there being better than the soil of the mainland and within two years the Island was carrying 41 per cent of the colony’s total population.

The early chapters of House of Commons describe the social and political unrest of the Sydney colony with the malign influence of the New South Wales Corps, a regiment described by the author as the dregs of the British Army. In a lawless environment, especially when the office of Governor was vacant, they were a law onto themselves. They acquired and traded in quantities of liquor and, such was their control of the trade, that they became known as the Rum Corps.[3]

Once the colony had survived the early years of near famine and became self-supporting, a key issue was the confidence of the population in the Governor, who in the early years had autocratic powers. And each Governor was responsible to the representative of the British Government, usually the consecutive Secretaries of State for War and the Colonies, each of whom spelt out strategic considerations in Britain guiding their colonisation policy.

Fifteen years after the arrival of the First Fleet in Sydney, during 1803 and 1804, three different consignments had been sent from Britain to Van Diemen’s Land, each made up of convicts, soldiers, civil and military officers, together with a few free settlers.[4] It is the colonial settlements of New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land, and the response of the British Government to the administration of those settlements, that comprise the principal focus of A House of Commons.

The historian John Hirst was one of the first writers on the transformation of the penal colony of New South Wales into a self-governing colony and democracy.[5] Hirst contested the notion that New South Wales began as a penal colony; rather, it began as a colony of convicts in which ‘[t]he early governors were given no instruction as to the punishment of the convicts. The first job of the governors was survival; the second was economic growth, so that the colony could pay for itself.’[6] Another writer, Grace Karskens, with her magisterial work The Colony: A History of Early Sydney [7], is a notable contributor to our understanding of the early colonial period in Sydney. She, like Wakeling, provides not only details of the early settlement but also an assessment of the contribution of early governors and the extent to which they followed official British instructions to the letter.[8]

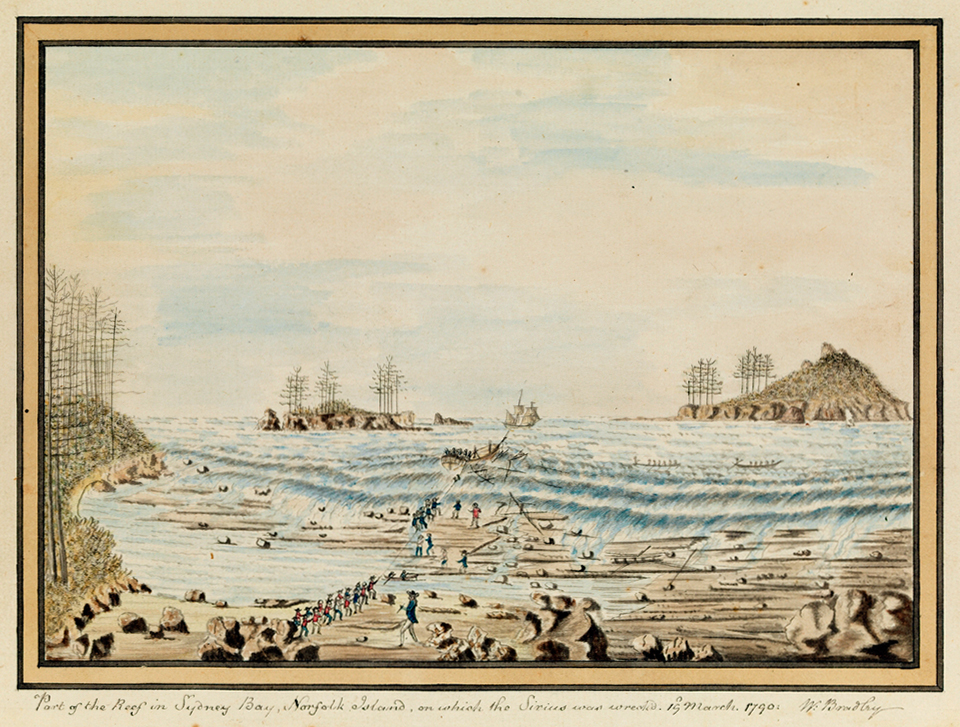

‘Part of the reef in Sydney Bay, Norfolk Island, on which the Sirius was wreck’d, 19 March 1790’, by William Bradley (dictionaryofsydney.org)

House of Commons is well-written and thoroughly researched, but some aspects of the publication, such as the lack of illustrations, limit its appeal for general readers. Overall, it is best suited to the education market, particularly for history students at senior high school level or university undergraduates. Readers are provided with good detail in the book’s index, but there are minor errors in the index, such as the listing of Lord Elgin, Lord Liverpool, Lord Stanley etc. under ‘L’ and not under their surnames. Putting that aside, for students, the two detailed appendices to the book provide valuable study guides: Appendix A: Table of Key People and Events, which covers Monarchs, Prime Ministers, Colonial Secretaries, and Governors etc. from 1780 to 1870; Appendix B: Key Documents, which lists statutory instruments of the United Kingdom and colonies in chronological order.

In summary: House of Commons for a Den of Thieves is recommended, but mainly as a textbook for students.

* John Myrtle was principal librarian at the Australian Institute of Criminology, Canberra. He has produced Online Gems for Honest History, drawing upon his extensive database of references, and has written a number of book reviews for us (use our Search engine), a study of industrial action in the Sydney media industry in 1966-67, an article on Edward St John QC, and the history of the Arthur Norman Smith lectures in journalism.

[1] A House of Commons for a Den of Thieves (back cover).

[2] Brian Fletcher, ‘Phillip, Arthur (1738-1814)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography (1967)

[3] A House of Commons for a Den of Thieves, 5.

[4] James Boyce, Van Diemen’s Land, Black Inc., Melbourne, 2009, 20.

[5] John Hirst, ‘How did a penal colony change peacefully to a democracy?’, Australian History in 7 Questions, Black Inc., Melbourne, 2014, 27. See also his Freedom on the Fatal Shore: Australia’s First Colony, Black Inc., Melbourne, 2008.

[6] ‘How did a penal colony change peacefully to a democracy?’, 33.

[7] Grace Karskens, The Colony: A History of Early Sydney, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2009.

[8] The Colony covers the contribution of five governors, from Arthur Phillip to Lachlan Macquarie.