The Divided Sunburnt Country series

‘Divided sunburnt country: Australia 1916-18 (19): The 1916 coal strike’, Honest History, 13 December 2016

‘The strikes and upheavals, political and industrial, we see around us are the manifestations of a deliberate policy which aims at destroying society as it now exists.’ So said Prime Minister Hughes, addressing the great and good of Melbourne at the Lord Mayor’s Dinner on 9 November. Central in his thoughts was the coal strike, which had commenced on 1 November was to continue for some weeks. It involved miners in New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania and Queensland. While it went on, Labor finally split, with the election of Frank Tudor as the leader of the anti-conscription, anti-Hughes group in Caucus.

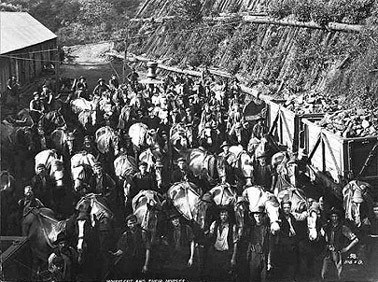

Miners and pit-ponies, Illawarra, c. 1900 (Migration Heritage NSW/NLA)

Miners and pit-ponies, Illawarra, c. 1900 (Migration Heritage NSW/NLA)

Having just lost the conscription plebiscite – though the votes were still to be finalised – Hughes, along with those attending the dinner, and his supporters across the country, saw the coal strike as a further blow to the efforts of loyal Australian Britishers to pursue the war against the Kaiser and for freedom. ‘It seems like the exaggeration of misfortune’, said the Sydney Morning Herald’s editorial writer, ‘that in the midst of war we should find ourselves at grips with a great coal strike’.

In a counter blast, the Australian Worker asked rhetorically, ‘How many of the Coal Barons and the newspaper proprietors supporting them would like to stand knee-deep in water, a thousand feet below the earth’s level, stripped to the waist, dirt-begrimed, in artificial light, breathing artificial air, for a few shillings a day?’ Like those who opposed conscription, those who supported the strikers did not necessarily oppose the war effort but they objected to what we would today call ‘collateral damage’, in this case damage to coal miners.

Industrial unrest on the home front during war is always problematic. It upsets the ‘win the war’ people at the time and it tends to be ignored by the commemoration industry decades later. To both these groups war is about everyone doing their bit and, if worst comes to worst, ‘the fallen’ dying heroic deaths and being remembered down through the years – or at least on Anzac and Remembrance Days. On the other hand, the extra effort demanded from workers under stress is likely to bring out demands for better wages and conditions. There may also be workers who take advantage of the need for their output and drive bargains that they might not have achieved in peacetime. This was the case in World War II as much as in the Great War.

In 1916, the NSW miners’ claims were long-standing and centred on a demand for a 44-hour week for miners and all colliery workers. Pursuing their demands, ‘they threatened to close down civilian industry, transport, public services, troop transports and wheat exports’, summarises Joan Beaumont. Bypassing the Arbitration Court, Hughes took action under the War Precautions Act and set up a special tribunal which granted the miners’ main demands.

A sigh of relief will be breathed everywhere [said the Sydney Morning Herald] now that the news of an immediate settlement of the coal strike is announced … The strikers have gained their point; and it is unnecessary to challenge the process by which finality has so far been reached. Now that the terrors of a possible cessation of industry, transport, and the ordinary amenities of civil life have been lifted, we must take up the old burdens and carry them on. The community breathes again. But the lesson of a strike in time of war has been set. Has it been learned?

Wallsend colliery, 1897 (Coal and community/UNCLE)

Wallsend colliery, 1897 (Coal and community/UNCLE)

Governments and people during war are always sensitive about ‘fifth columnists’ and behaviour that seems treasonous. In 1916, such suspicions were directed particularly at the Industrial Workers of the World, the IWW or ‘Wobblies’. The IWW were accused of fomenting the coal strike. ‘I.W.W.-ism is at the bottom of the trouble’, muttered the Melbourne Argus on 2 November and other newspapers made similar remarks. Hughes, too, was convinced – or said he was – that the strike was ‘the work of men who, calling themselves by many names, or by no name, are in effect anarchists; assisting them for their purposes is a certain section who are, as I have said, against the Empire’. Somewhere in that heinous coalition lurked the IWW.

There was some evidence for such claims. Some Broken Hill miners had worn badges bearing an IWW slogan, ‘If you want the 44 hour week then take it!’ Tom Barker of the IWW, who had been a leading opponent of conscription, now said the coal strike showed that ‘militant and aggressive tactics alone will get results’. His syntax was a bit scrambled but he probably meant that only militancy would cut through.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.