The Divided Sunburnt Country series

‘Divided sunburnt country: Australia 1916-18 (18): The Prime Minister is determined to carry on’, Honest History, 26 November 2016

The referendum (plebiscite) had been held on 28 October. Prime Minister Hughes was the guest of honour at the Lord Mayor’s banquet in Melbourne on 9 November. He spoke at length – and with passion if the text is any indication.

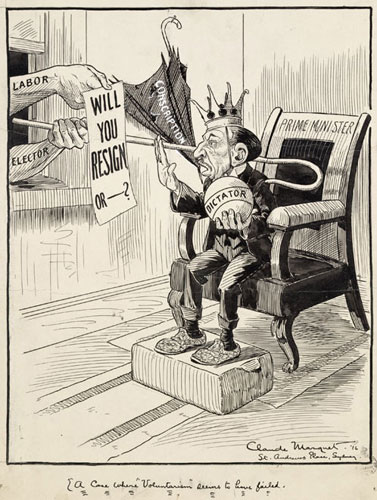

Hughes after the plebiscite, Claude Marquet, Australian Worker, c. January 1917 (Wikimedia Commons)

Hughes after the plebiscite, Claude Marquet, Australian Worker, c. January 1917 (Wikimedia Commons)

Although the referendum result had not yet been formally declared, the prime minister began, it was clear that the government’s proposal had been defeated, albeit narrowly. There was a majority against of less than 80 000 out of 2 ¼ million votes. (The final margin was 74 000.) ‘The citizens of the Commonwealth, then, looked at as a whole’, said the prime minister, ‘are divided into two camps of almost equal size’.

As many commentators did at the time and since, Hughes distinguished between attitudes to conscription and to the prosecution of the war.

The result of the referendum settles one point, and one point only – that we may not have recourse to compulsion in order to provide reinforcements for oversea service during the war. It does not in any way affect our existing powers under the Defence Act, although it does limit the extent to which these ought to be exercised; and, of course, it cannot affect in any way Australia’s obligations to the Empire during this war. (Cheers.) The people, misled by gross misrepresentations, have declined to entrust the Government with the powers asked for.

He also saw the result as significant for the future of democratic government.

Certainly, this refusal on the part of a free people to make sacrifices to defend their freedom will be used as a proof of the unwisdom of submitting great national issues directly to the people (hear, hear) but, while we regret the decision, considering the odds against us, there is no need to be discouraged. (Cheers.)

We must remember that this is the first time in history the whole people have ever been asked to make the many and great sacrifices which war entails. When we recall the fact that practically one half of the electors were prepared to make them, and that a considerable majority would surely have done so if they had not been deliberately deceived by false statements, we have no reason to say that Australia as a nation has proved herself unworthy. (Great cheering.) I venture to say that there are few, if any, nations who would have come through such an ordeal with greater credit. (More cheers.)

The government had to accept the verdict, ‘”but I feel certain that very many Australians already regret a vote which now, when it is too late, they see has brought joy into the camps of our mortal enemy, and made evident to all what is the policy of those mainly responsible for the anti-conscription campaign”. (Hear, hear.)’.

The reader can almost see Hughes bouncing from one foot to the other in his characteristic style as he warmed to his task. In front of this sympathetic audience, he was able to let rip.

What must be the feelings of tens of thousands of loyal Australians who, misled by the outrageous misrepresentations of designing men, voted “No” when they read in this morning’s press the enthusiastic approval of their action by the German press? Professor Manes, in an article in the “Volkische Zeitung”, says “The result is the sharpest condemnation of the whole policy of Mr Hughes, who is the most noisy and abusive Prime Minister of the enemy countries. It means the complete defeat of the loudest advocate of a commercial war against Germany. It means that the Australian force cannot be maintained at its previous strength, and it means that the other dominions cannot consider the introduction of compulsion.”

Several papers declare that the result amounts to the defeat of Germany’s most prominent opponent amongst the dominions, and that Australia’s example will be followed by the other dominions. Is there one man or woman who voted “No” and who loves Australia who does not feel humiliated and ashamed to see in what light their action is regarded in Germany? (Applause.)

These words of commendation from those whose hands are red with the blood of our Australian soldiers, these words of jubilation from the slayers of women and children, these marks of approval of those inhuman monsters who have with fiendish malignity inoculated British prisoners with foul diseases, must burn themselves into the very soul of every true Australian.

To be patted on the back by Germany is to feel the hand of a leper upon one’s face. Can any loyal Australian who voted “No” now doubt that they have played the game of Germany?

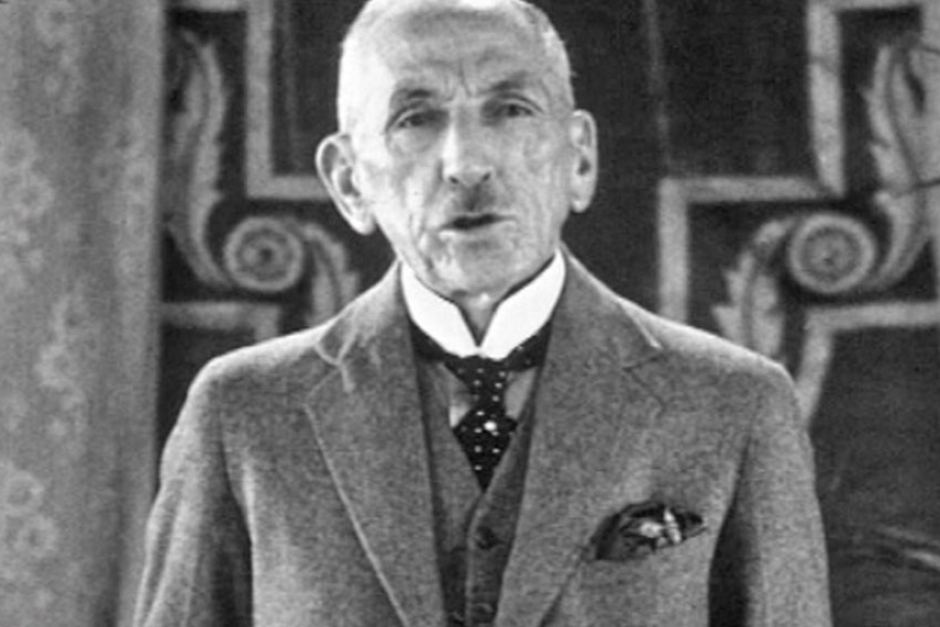

Video still of Hughes delivering a speech (ABC News)

Video still of Hughes delivering a speech (ABC News)

Hughes then turned to link the motivations of the leaders of the ‘No’ side to the people who were leading the coal strike that was at that time causing great disruption. There was an implication, too, that the Industrial Workers of the World were behind both the defeat of the referendum and the coal strike. IWW members were under arrest for arson and murder. (We will have more soon on both the coal strike and the IWW.)

Hughes was still confident that he had the support of most Australians.

I believe that the great mass of the people of Australia are loyal to the Empire, and are resolute to fight on the side of Britain and her allies to the end. (Cheers). I said during the campaign, and I repeat it now, that something more than the mere question of compulsory enlistment for reinforcements was involved in the referendum.

It is perfectly plain that there is in this country a number of persons who are opposed to this war, who are against the Empire, who will do all they can to prevent Australia doing her duty as a part of the Empire. The strikes and upheavals, political and industrial, we see around us are the manifestations of a deliberate policy which aims at destroying society as it now exists. They are the work of men who, calling themselves by many names, or by no name, are in effect anarchists; assisting them for their purposes is a certain section who are, as I have said, against the Empire.

This is the situation with which Australia is faced. Fighting abroad for our liberties against the great enemy of liberty, Germany, we are menaced at home by men who seek to stab the Empire in the back; by men who are against this war for liberty imposed upon the civilised nations by the great military despotism of Germany; by men who seek to force upon us an intolerable tyranny, and to make government impossible.

What must be the duty of any Government worthy of the name under such circumstances? It is to carry on the war with vigour, to prove to the Empire and to the world that the heart of Australia beats true; that it owes its existence to the Empire, and realises that only through the decisive defeat of Germany can the Commonwealth maintain its liberties and its destiny. (Applause.)

After discussing arrangements for men currently in camp in anticipation of conscription proceeding, the prime minister concluded along the lines of ‘Watch this space’. The path to a second plebiscite was already being mapped out.

We propose to press on with that policy upon which we were elected, both in regard to the war and to matters arising out of the war. We shall endeavour, despite the limitations imposed by the people’s verdict, to enable Australia to play her part creditably on the field of battle. (Cheers.) So long as the people of Australia support us, we shall endeavour to carry out what we believe to be the great and over-powering desire of the citizens of the Commonwealth.

It would be easy for me, were it not for certain circumstances which will be obvious to all[1], to amplify very considerably the outlines of the policy which I have ventured to set before you tonight, but I think that the record of the Ministry which I have the honour to lead is one which has earned the commendation of a very large section of the people of Australia. Along the lines of that policy we intend to proceed. We believe that the bulk of the people of Australia desire such a policy, and as long as we are permitted to give effect to it we shall carry on. (Cheers.)

When we find that to be impossible we shall appeal to the people. (Loud cheers.) We shall appeal to the people in such a way that not a section of the Parliament, but the whole Parliament will come before them. (Loud cheers.) I hope that when we meet here again we shall meet in peace, and with the knowledge that during the most trying time in the history of the Empire Australia did her duty and did it well.

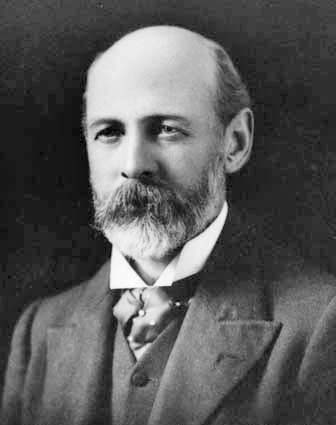

Joseph Cook, former leader of the opposition, who became Minister for the Navy in February 1917 (Alchetron.com)

Joseph Cook, former leader of the opposition, who became Minister for the Navy in February 1917 (Alchetron.com)

Earlier in the day, a meeting of the Melbourne City Council had unanimously resolved as follows: ‘That this council expresses its appreciation of the action of the Prime Minister (Mr. Hughes) in his patriotic services during the referendum campaign, and his efforts to send help to the Commonwealth soldiers on active service in defence of the Empire’.

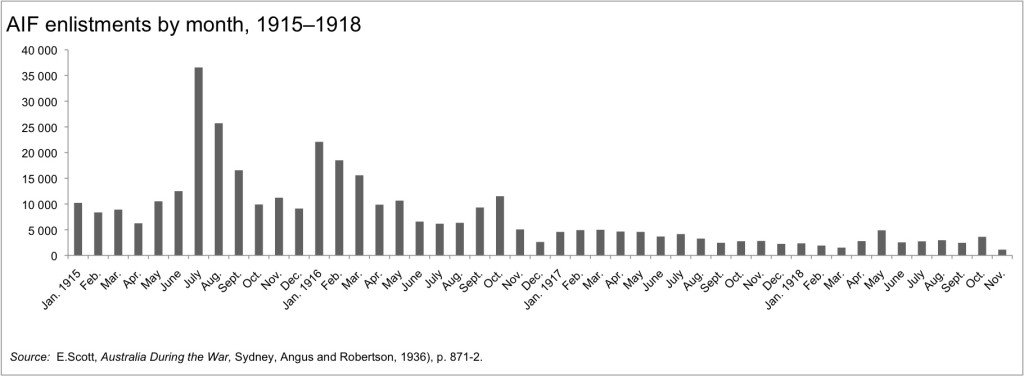

Meanwhile, as if to confirm the need for conscription, voluntary enlistments were falling in November 1916 to 5055, less than half the level of October (11 520). They did not reach the November 1916 level again for the rest of the war (see the graph below).

See also a recent article from Joan Beaumont on the first conscription referendum (plebiscite) and Hughes’s tactics. Beaumont makes an important point:

[I]f the Yes campaign had prevailed, making the Australian Imperial Force a conscript army, Australia might not have developed such a resilient mythology about the men who did volunteer. And our leaders today might be telling a very different story about the place that the Anzac legend, a cult of the volunteer, plays in our national identity and memory of war.

Courtesy of Joan Beaumont: see her Broken Nation, Appendix 2, using figures from Ernest Scott

Courtesy of Joan Beaumont: see her Broken Nation, Appendix 2, using figures from Ernest Scott

Note

[1] Hughes had been expelled from the New South Wales branch of the Labor Party in September, though he was still technically Labor prime minister when he spoke on 9 November. He and his supporters walked out of the Labor Caucus on 14 November and formed a National Labor government. This became the Nationalist government in February 1917, including opposition leader Joseph Cook and some of his Liberal colleagues. The Nationalists then won the election in May 1917.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.