Frank Cain*

‘The Petrov Affair and fake documents: another look’, Honest History, 15 March 2017

In a previous edition of Honest History, David Stephens referred to fake news and the seeking by Dr HV Evatt, then Leader of the Opposition, of the truth behind Russian documents connected to the Petrov Affair 1951-55. David’s essay is worthy of enlargement as follows.

Operation Venona

The history of the Petrov Affair commences early in 1948 with the launch of ‘Operation Venona’ by the United States Army’s Signal Security Agency (SSA) at Arlington Hall, Virginia, near Washington. The intention was to decipher many thousands of Russian diplomatic cables the SSA had collected in the United States and elsewhere, including Australia. The Australian involvement sprang from the opening, thanks to Dr Evatt’s participation as Minister for External Affairs, of a Russian embassy in Canberra in November 1943.

Petrov (Herald Sun)

Petrov (Herald Sun)

The Australian Army’s collection of cables to and from Moscow between 1943 and 1949 amounted to 4000 cables in five-figure codes. The Army sent them to Arlington for translation, but only 400 could be deciphered. The Russians were warned by an American that their codes were broken and Venona was shut down in 1948. The closure of Venona left 30 000 messages unread but, with the expansion of the Cold War, Russian espionage techniques came under closer scrutiny and US decoding recommenced in 1949.

The Venona operation was supposed to be highly secret, but there was leaking of the names of Australians, such as Ian Milner, a former diplomat, and Walter Clayton, a communist collector of information for Russia. These could have been planned leaks which contributed to the increasing disfavour into which Australia was sliding, due to an American perception that Australia was judged to be too radical.

There was particular dislike in Washington towards Dr Evatt for his introducing an independent Australian foreign policy which included building a bridge of diplomacy to the Russians and opening the Russian embassy in Canberra. The US ambassador in Canberra condemned the Chifley Labor government by sending disparaging reports to the State Department; he was joined by his Naval Attaché sending equally unfavourable reports to the Defense Department.

The outcome of these American actions was that in June 1948 the Pentagon banned the transmission of all classified information to Australia. The British feared the loss of US technology for their missile testing range at Woomera. Chifley and the British Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, agreed on 16 March 1949 that Australia would establish the Australian Security Intelligence Organization (ASIO) as a way of regaining American support.

Elections were held in December 1949, resulting in the replacement of the Chifley Labor government by the Liberal-led Menzies government. The new government had ASIO pursue the alleged ‘nest of traitors’ said to have existed in the External Affairs Department when Dr Evatt was minister in the 1940s.

Petrov’s defection and his fake papers

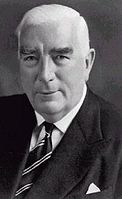

Menzies (Wikipedia)

Menzies (Wikipedia)

Vladimir Petrov arrived in Sydney on 5 February 1951 to go to a position as coding clerk at the Russian embassy in Canberra. In April 1954, he defected and produced embassy papers including numerous names connected with Venona. Prime Minister Robert Menzies was a Cold War warrior, who had tried unsuccessfully in 1950-51 to ban the Communist Party. He used the Petrov defection to call a sudden election just for the House of Representatives, and then a Royal Commission into espionage.

Some Venona names had leaked, but obtaining additional Venona names from the Americans to bring before the Royal Commission was unlikely. That problem was solved by Petrov appearing with his papers containing Venona names gleaned from documents in the Russian embassy. The names he produced included some Russian code names.

Historians have long considered the Petrov papers to have had an element of fakery, especially as almost half the documents were written by Australians. One of the two papers written in Russian was named the ‘Moscow letters’ and was dated January to November 1952. This material contained 39 Australian names and was purported to be instructions to the spy master in the embassy, now Petrov himself.

Petrov, this reticent ex-coding clerk with limited English language skills, was instructed to expand his operations by ‘timely collection of data’ and to recruit ‘lawyers of your acquaintance’ for duties. Most absurdly, he was to place ‘trusted agents’ in the Australian spy force in Russia so these people would be exposed as non-genuine agents.

More outlandishly, Petrov was instructed to train two embassy officials, neither of whom spoke English, to be intelligence agents. Petrov was acquainted with Madame Ollier of the French embassy, from whom he was told to obtain the French diplomatic code, no less.

It has been argued that these letters were written in Australia rather than Moscow. Two Sydney trade unionists who had visited Russia said the letters were fakes, as the material in them was so specific that it could only have been written in Australia. Dr Evatt said that the letters were fakes and could have been prepared by a Russian speaker with access to a Russian typewriter.

Photographers at the Royal Commission, Sydney (MOADOPH/Mitchell Library/Jack Hickson)

Photographers at the Royal Commission, Sydney (MOADOPH/Mitchell Library/Jack Hickson)

Menzies appointed three Supreme Court judges (Ligertwood, Owen and Philp) from Adelaide, Sydney and Brisbane as Royal Commissioners and the Royal Commission began sitting on 17 May 1954. Unsurprisingly, the 1954 elections (29 May) went well for Menzies – he won fewer votes than Labor but more seats. Petrov was not inexpensive: he was paid £10 000 in cash ($100 000 in today’s currency) on arrival in the ASIO safe house.

Enter Dr Evatt

Dr Evatt, leader of the parliamentary Labor Party since 1951, appeared before the Commission to defend two of his staff named in the papers. However, when Evatt tried to call Dr Michael Bialoguski, the Commissioners stopped him appearing. Bialoguski was a shadowy figure who colluded with Petrov to purchase Scotch whisky from the Sydney wholesalers with an embassy discount and sell it to the night clubs.

The highest point in this farce occurred when Walter Clayton appeared. Venona described Clayton working with the Russians in collecting material from communists for Moscow. On examination, Clayton said he knew no Russian officials and never visited the embassy. The shocked judges and ASIO officials sat fuming in court over his blatant lying, knowing that their refutations required the use of Venona information which was not forthcoming. These novel circumstances explain why the Commissioners could make no recommendations for prosecutions against the suspects.

The Commissioners referred to Venona, however, when remarking of Ian Milner, who had handled some documents, that he was culpable on the basis ‘of information we have seen’. In 1996, all the Venona messages were publicly released by the Americans. The deciphered Australian cables were collected together as the ‘Fifth Venona Release Volume 3 of 7. October 1996’, containing 330 pages. (There is background material on the Venona release here but apparently not the Canberra material.)

The Royal Commission ended on 19 May 1955 and Dr Evatt provided a close analysis of the Commission’s report on its parliamentary tabling in October. Evatt’s scrutiny included his announcement of having written to VM Molotov, the Soviet Foreign Minister, in February 1955, claiming Petrov’s documents were fakes and seeking a joint investigation of their authenticity. He was immediately jeered by government members.

Evatt (Wikipedia)

Evatt (Wikipedia)

Evatt was a friend of Molotov through meetings in the United Nations and elsewhere, but he was asking too much of Molotov. Molotov could not put Russia’s intelligence gathering to open examination and the reply that the Petrov material was a fabrication came not from Molotov himself, but from the Chief of the Press Department of the Soviet Foreign Office.

Other contradictions emerged in the Royal Commission’s report, but public support swung behind Menzies. He capitalised on this by calling elections for both Houses on 10 December 1955 and won with an increased majority. Thus was launched the Menzies era and the eclipse of Dr Evatt, who retired as Labor leader in 1960.

* Frank Cain is a Visiting Fellow in the School of Humanities and Social Sciences at UNSW Canberra. This article is drawn from the author’s Terrorism and Intelligence: A History of ASIO & National Surveillance, Australian Scholarly Publishing, North Melbourne, 2008. Frank Cain has written widely on Australian labour history and aspects of security and defence policy. For other espionage-related material on the Honest History site, use our Search engine with terms such as ‘ASIO’, ‘Blaxland’, ‘Burton’ and ‘Horner’.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.