‘Australian resilience in 1929-32 has relevance to post-Pandemic Australia, as Joan Beaumont’s strong synthesis shows’, Honest History, 5 September 2022

Claire EF Wright reviews Joan Beaumont’s Australia’s Great Depression: How a Nation Shattered by the Great War Survived the Worst Economic Crisis it has Ever Faced

Joan Beaumont’s wide-ranging account of Australia’s Great Depression is a welcome synthesis and general history of this important episode in Australia’s past. Beaumont examines the ‘worst years’ of the Depression (1929-32), with the central theme of resilience: ‘how did Australians survive?’ Although Beaumont’s focus on resilience has been criticised elsewhere (for example, by Marilyn Lake) as ‘conservative’, the question is, I believe, a good one. History is often told as a series of crises and structural breaks with tradition, with less attention to less dramatic but equally interesting matters of endurance of institutions and cultures despite immense upheaval.

Joan Beaumont’s wide-ranging account of Australia’s Great Depression is a welcome synthesis and general history of this important episode in Australia’s past. Beaumont examines the ‘worst years’ of the Depression (1929-32), with the central theme of resilience: ‘how did Australians survive?’ Although Beaumont’s focus on resilience has been criticised elsewhere (for example, by Marilyn Lake) as ‘conservative’, the question is, I believe, a good one. History is often told as a series of crises and structural breaks with tradition, with less attention to less dramatic but equally interesting matters of endurance of institutions and cultures despite immense upheaval.

Beaumont begins where her previous work left off: the end of the First World War. The global context for Australia’s Great Depression was a world uneasy with a post-War world order. The round-robin of war debts, overproduction of commodities, disintegration of the gold standard and devolving of economic co-operation in favour of nationalism and protectionism, all exposed the fractures of the global economy well before (and well after) the stock market crash of 1929.

In Australia, in the wake of damages wrought by our first major conflict, national economic policy in the 1920s pursued ‘men, money and markets’: men in the form of targeted immigration programs to replace the folks lost in the War; money from London capital market bond issues to pay for new ‘visionary schemes’ of public infrastructure; markets through the development of domestic manufacturing as well as imperial preference markets for Australian exports.

Although these initiatives had noble goals, they were only moderately successful, with inadequate planning and overleveraging meaning that Australia was seen as an increasingly risky borrower. The expansion of the economy had stalled by 1927, and on the eve of the Wall Street crash the price of Commonwealth stock and the price of wool and wheat was falling, while the external interest bill was rising. James Scullin’s Labor government came to power days before the October 1929 stock market crash and was immediately faced with a ‘toxic mix’ of angry unions, increasing unemployment, and national debts of a scale that severely restricted policy options. The recession soon slipped into the Depression.

Beaumont argues that the Scullin government had little capacity to mitigate the most disastrous outcomes of the Depression. Automatic stabilisers combined with the government’s constrained capacity to borrow, and some specific misguided decisions were to blame, with rising unemployment leading to a decline in tax revenue and shrinking global demand for Australian exports reducing tariff and excise revenue, worsening already pretty terrible budgetary problems. The modern welfare state was in its infancy, with concepts of expansionary fiscal policy – of the sort implemented by the Rudd government in the 2007-08 global financial crisis – still developing (Keynes’s General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money was not published until 1936).

Although eventually Federal government support came in the form of the ‘susso’ or sustenance system and various infrastructure relief works, it often fell to the State governments, as well as various religious and charitable organisations, to fill the gaps in the social safety net. Community and family resilience was supported through municipal committees, trade unions, cooperative stores, associations of the unemployed, returned soldiers organisations, school groups, philanthropists and charities and churches. Communities enabled people to pool resources and employ inventive strategies of self-help while families provided the emotional stability that was often the essence of individual resilience. This section is where much of the new research lies, with archival work providing an excellent contribution to existing social, local, and family histories of the Depression.

Beaumont also examines how the Depression impacted on a range of groups and discusses the way relative regional prosperity and policy options accrued unevenly based on resources, climate, population density, industrial structure and so on. The working class male unemployed – the common image of the struggles of the era – peaked at up to one third of all union members in the third quarter of 1932. South Australia and New South Wales were particularly hard hit, with the building, construction and manufacturing industries recording the worst levels of unemployment.

Scullin Ministry sworn in, Government House, Canberra, 22 October 1929 (Wikipedia/WJ Mildenhall). Fenton second from left, Lyons third from left, Theodore fifth from left, then Scullin; Forde fourth from right, Beasley far right.

Meanwhile, the collapse of commodity prices had a ruinous impact on rural communities, and those at either end of the age (under 21 or over 55) spectrum fared comparatively worse. Women outside family units, homeless folks, those in working-class suburbs, and non-white Australians (both Indigenous and new migrants) are highlighted as those who were particularly vulnerable to the vicissitudes of economic crises.

In many cases, existing marginalisation was exacerbated by failures of government policy with, for example, Indigenous people prevented from accessing welfare support, and women subject to unequal wages and a lack of support in the event of divorce. On the other hand, large businesses like BHP and people in the middle and upper-middle classes were spared the worst of the Depression’s effects, with the stock market recovering in a matter of months. Through all of this, Beaumont convincingly argues that it is difficult to generalise about Australia in the Depression, though this somewhat contradicts her aim to present a ‘national’ history of the crisis.

Reviews of Beaumont’s work as a general history have followed the predilections of the reviewers and I am no different. My key concern is the extent to which Beaumont’s economic story of the Depression contributes to the considerable, albeit half a century old, literature on the matter. Beaumont points to her reliance on Schedvin’s authoritative Australia and the Great Depression (1970) and tendrils of this book and Gregory and Butlin’s edited collection, Recovery from the Depression (1988), can be found throughout her narrative: internal structural weaknesses in the Australian economy that preceded the 1929 Wall Street crash; the failures of government macroeconomic policy; currency and international capital flows; paying for national debt; the importance of global trade; and the development of Australia’s manufacturing industry. Beaumont’s focus on the importance of understanding regional and local economic outcomes echoes GD Snooks’ Depression and Recovery in Western Australia (1974), though it covers much broader territory across the continent.

For the most part, Beaumont surveys the economic history literature, adding little new information, critique, or perspective on this work. There are occasional glimpses of what could be possible in an economic-historical reappraisal of the Depression, with Beaumont’s discussion of charitable and voluntary work highlighting its importance as a form of work, a policy alternative, and a source of economic resilience in crisis. Historians such as Melanie Oppenheimer have highlighted the importance of volunteering as an economic activity and, reading Beaumont’s book, I was struck by the extent of work yet to be done in economic history to analyse volunteering as a form of work and labour.

Beaumont connects this material to the social and community aspects of the book but does not provide any new insights on the broader shape of the Depression, nor recovery. This misses a key opportunity to contribute to existing economic history literature, though it is an important reminder that there are forms of economic resilience other than those suggested by mainstream economic theory and that we ignore them to our detriment.

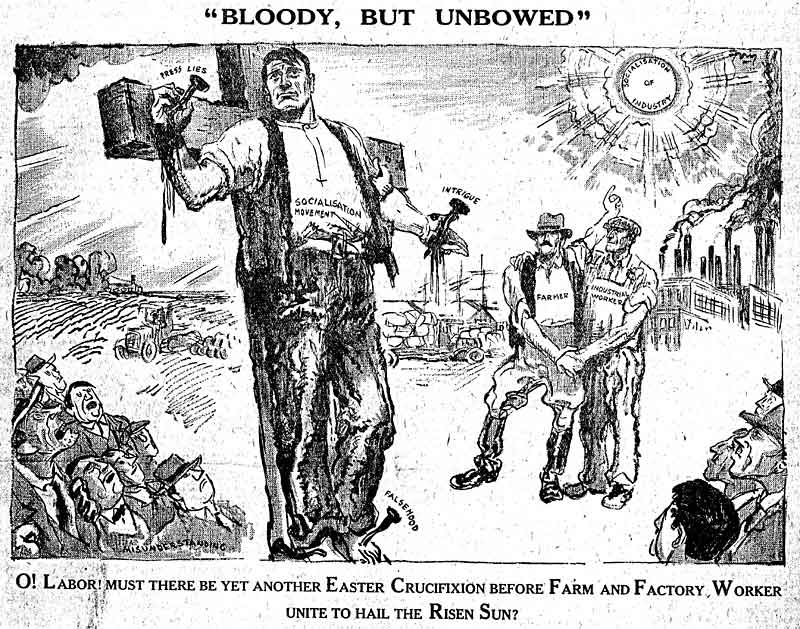

Cartoon in support of the socialisation movement of the early 1930s, artist unknown (RedFlag)

To repeat, the main strength of Australia’s Great Depression lies in its synthesis. While most of Beaumont’s economic story does little to add to major work on the subject from the 1970s and 1980s, her ability to range across economic, political, social and race histories provides a compelling narrative. In the age of increasingly narrow specialisms, more of this integration is sorely needed. The connection of economic and other Australian histories is also particularly welcome. Treating the Depression as a purely economic issue, or indeed an entirely political or social one, weakens our understanding of the past.

This is also a history very much connected to the present. The continuing COVID-19 pandemic and the chaos wrought by the crisis itself, as well as the fracturing of federalism in favour of state and local government solutions, has echoes of the Great Depression. Connecting history to present concerns is enriching to our discipline and (I hope) to our social and political discourse.

*Claire EF Wright is an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DECRA) Fellow (2022-25) at the University of Technology Sydney, working on the first history of Australia’s corporate women across the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. She is the author of Australian Economic History: Transformations of an Interdisciplinary Field (ANU Press, 2022).

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.