Edwards, Clive T.

‘With respect to John Burton’, Honest History, 10 September 2014

Rob Foot’s article (‘The curious case of Dr John Burton’, Quadrant, November 2013) denigrates the character and contribution of John Burton by reference to incidents that were not central in either the historical context or in the context of Burton’s life.

Historical context

Burton became head of External Affairs in 1947. He was 32. Japan’s occupation of Vietnam, Burma, Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia, all colonial territories, had just come to an end. The respective colonial powers, France, Britain and Holland, had deserted the region in the early days of the Pacific War. Britain had made it clear to Australia that the nation was on its own but that Britain expected Australia to continue to contribute to the allied war effort in Europe.

Up until the early 1940s Britain had essentially determined Australia’s foreign policy. Curtin and his successor Chifley saw conflict between Australia’s own distinct interests and that of Britain and both wanted a greater emphasis on Australia’s national interest in the formulation of Australian foreign policy. This switch needed a catalyst and the appointment of Burton as Secretary of External Affairs filled the bill.

The significance of Burton’s appointment quickly became apparent. The colonial powers assumed that they would return to their former colonies and resume business as usual: a foreign elite extracting wealth for the benefit of the colonial country, largely ignoring the plight and aspirations of the majority of the local people. Burton saw it differently. He was aware of the nascent development of indigenous political leadership in Indonesia and played a constructive role in the acrimonious but successful independence struggle there. This was a major preoccupation of Australian foreign policy in the late 1940s. It gets a brief, one sentence, incidental mention in Foot’s article (p. 51) and yet it had important implications for his central theme, the security relationship between Australia, Britain and America.

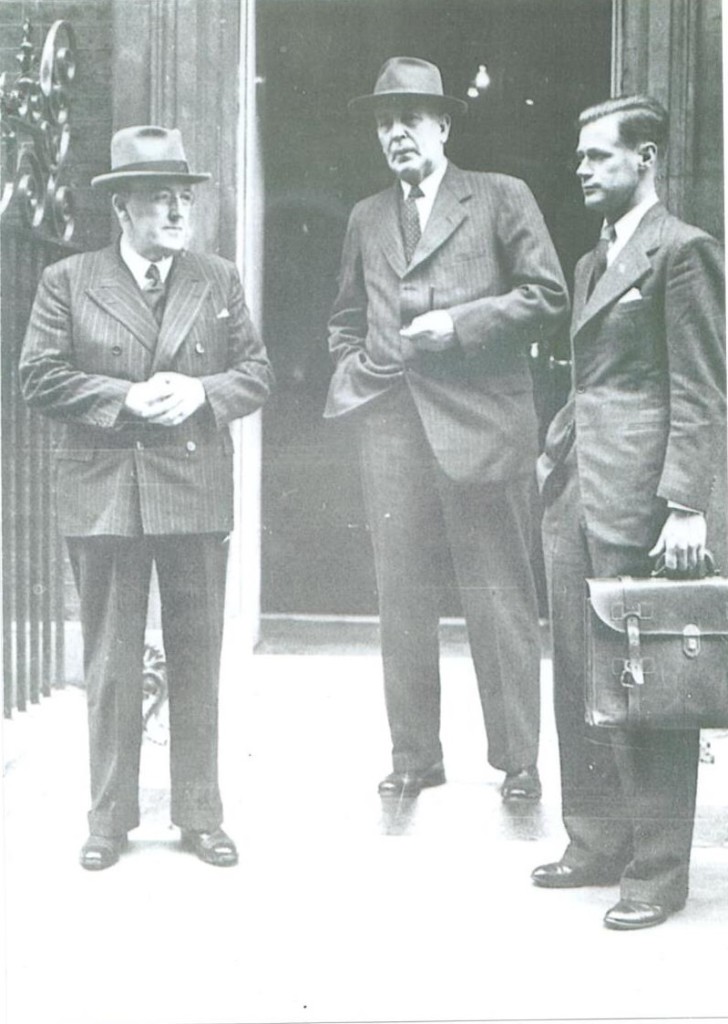

JA Beasley, Australian High Commissioner to London, Chifley and Burton, 10 Downing Street, 1948 or 1949 (supplied: Pamela Burton)

Burton had the ear of Evatt and quickly organised a successful appeal to the United Nations Security Council. This was designed to halt a Dutch invasion of Indonesia. Can you imagine how the intelligence community in Britain and Holland responded to this assertion of independence by what they continued to regard as essentially a British possession? Can you see them continuing to provide Australia with intelligence gathered by Britain and Holland which was designed to return the colonial powers to their pre-Pacific War status and which would have provided information on the growing support within those former colonies for indigenous leaders such as Sukarno in Indonesia? That information could have been used by Evatt and Burton to strengthen the case at the United Nations for granting independence to Indonesia. If the flow of intelligence to Australia dried up at this time, one can well understand why. Foot notes that the flow of intelligence to Australia did dry up but does not mention a word of this background.

Burton was aware that the days of colonial rule in Asia were finished and that Australia would have to learn to live with newly independent countries in Asia. To that end, he judged that there was a need for Australia to be acquainted with emerging political leaders in Asia, a stance well ahead of prevailing attitudes in Australia. In many of our neighbouring Asian countries, the main independence movements were socialist or communist, or a mixture of both. For example, in the late 1940s Lee Kuan Yew was a leading member of a party that was socialist and included several avowed communists.

One might easily infer from Burton’s interest in these movements that he was sympathetic to communism. That would be incorrect. Burton was interested in the full range of independence movements in Asia, their relevance to the mass of the population in the respective countries, their viability and, most importantly, the implications they carried for Australia’s security. After all, Sukarno was an Indonesian nationalist, not a communist, and Burton saw the long-term relevance to Australia of supporting Sukarno over the Dutch. If you accept Foot’s characterisation of Burton as sympathetic to communism and most likely a Soviet spy, you have to explain this dichotomy, for at that time there was a separate, growing communist movement in Indonesia.

Chifley, Evatt and Burton realised that the Pacific War had irrevocably changed Australia’s world view. They made the decision to sharpen the focus on Asia in Australia’s foreign policy. They were pioneers of what very gradually became a more central feature of Australian foreign policy. They judged that their stance was in Australia’s long-term national and security interest and Australia earned a substantial amount of political credit in South East Asia in these years, a point that has been widely acknowledged.

Burton was an Australian nationalist first and foremost, not a lackey of Britain or any other country. He would have been every bit as suspicious of Russian motives in Asia (in Indonesia, for example, and in China) as he was of British or Dutch motives. This picture of Burton is very different from that painted by Foot.

Lifetime context

Burton left the External Affairs department in 1951 but he had really packed his bags when Menzies took over at the end of 1949. Burton left Australia in the early 1960s and spent the best part of his next 40 years building an international reputation in the field of international relations. He held chairs in London and America until he was well into his seventies. He played a leading role in the development of a new field of study, international conflict resolution, and his numerous books are now standard references for courses in this field at universities around the world.

Burton taught postgraduate students in both countries. It would seem remiss of both London and Washington to allow a Soviet agent such access and influence. Burton’s life should be seen in total. It ought not be distorted and denigrated by incidents which were peripheral and for which the best that can be said in most instances is that they amount to no more than innuendo and assertion.

Burton has not yet been accorded the attention he deserves as a very significant Australian who made path-breaking contributions in public life in Australia and in the academic field internationally. His day will surely come.

The last section of Foot’s article is highly speculative and very disparaging. Foot asserts that Burton was most likely a Soviet agent. Burton was close to both Chifley and Evatt. He would have had access to a level and range of intelligence much higher than that available to Milner or any other officer in the then External Affairs department. Had he been a Soviet agent, he would of necessity have sought asylum in Russia in 1950 if not earlier. He did not.

Burton’s character was at odds with this line of argument. He was always a ‘big picture’ man. This is exemplified by his awareness that colonialism in Asia was at an end, his role in the Indonesian initiative and his subsequent research. At the 1939 Bergen Conference referred to below, he met two Japanese researchers who told him that anti-economic depression action taken by the allied countries that denied Japan access to resources (minerals, rubber and other primary products) and markets in South East Asia would force Japan to expand militarily into Asia. Burton saw the implications of that prospect for Australia and on return to London a few days later apprised the Australian High Commissioner, Stanley Bruce. Bruce wrote to warn Menzies, who in turn replied that Japan was a close and loyal ally. Burton had grasped the big picture and put it in an Australian context. In his 1939 note to Bruce, Burton pointed out that if Japan did go to war, the crucial sea trade links between Australia and Britain would likely be disrupted and there was a need to start planning for that possibility.

Burton was a very proud man. He knew he had a lot to offer. He was quite aloof. He worked long hours and efficiently. He did not suffer fools or laziness and was a man of few but well-considered words. He was his own man, very independent and reluctant to rely on others. His farming experience in Canberra and Kent was in the same mould. He did not follow what his neighbours did in either location; he struck out on his own path and learnt from his own experience. He was the sort of person who stood back and summed you up. If he was interested in your line of argument he would enter the fray but often do so by turning your argument upside down and seeing what conclusions that led to, invariably a salutary exercise. It is difficult to envisage a person with that sort of creativity being a slavish, compliant Soviet agent. If officials in London, Holland and America struggled to understand an Australian nationalist in what they continued to believe was a dyed-in-the-wool British outpost, one can be confident that the same held for the Soviets.

Why did Burton go to the Soviet Union in 1939 while studying in London? Foot asserts that he was being recruited into either the MVD or GRU. He adds that, while at the London School of Economics, Burton

seems to have come under the influence of Harry Pollitt, Head of the British Communist Party. He was en route to a student conference in Norway [Bergen] when he diverted to Moscow, where he spent ten days. He later claimed to have had to sell his suit to pay for the fare, so the visit must have been of great importance. Quite possibly he went to offer his services, bearing a recommendation from Pollitt. At any event, Soviet intelligence would have been most intrigued with this bright young man from Australia who landed on their Moscow doorstep… (p. 52, my underlining highlights unsubstantiated assertions)

An alternative, less cloak-and-dagger explanation might be that Burton went to Russia to observe an alternative way of managing an economy. After all, he was pursuing a PhD in economics under the supervision of Lionel (later Lord) Robbins and capitalism was in considerable disarray in the 1930s.

The latter explanation may have had some truth but it also misses the spirit of the trip. John had recently married Cecily and this was their honeymoon. They went by boat to Leningrad. They visited Moscow, too, as tourists. Contrary to what they expected, they and other tourists were not hindered in where they chose to walk but were not allowed to take photographs. John did sell an old suit, not in Britain to get money to pay for an unexpected trip to Russia as Foot asserts, but in a government shop in Russia where clothes were bought and sold. He did not get much for his suit: 350 roubles or about 17 British pounds (1939 money).

Cecily did a lot better, selling a ‘swagger’ top coat for the rouble equivalent of 250 pounds. They used these non-convertible roubles to buy air tickets to Stockholm and, as Cecily wrote to family at the time, had three glorious days crossing Sweden to Gothenburg by the Gota Canal. From there they travelled by rail to Bergen in Norway for the Twelfth International Studies Conference. They were there on time but the conference was cancelled shortly after it began because war was declared.

John and Cecily compared Sweden and Russia and their impression was that the Swedish capitalist system, with its strong co-operative movement, delivered better outcomes: judged by housing, there seemed to be less inequality in Sweden and the quality of household products was higher and the range greater. In Russia, Cecily commented, walls were cracked, lights were broken, baths were scratchy, floors squeaked, meals were slow, plugs missing. They enjoyed Leningrad and Moscow but they were not blind, enthusiastic, uncritical supporters of the Soviet model.

Against this background it is quite salutary to re-read Foot’s account quoted above. It is fiction, not academic research. It is full of assertions (see underlines) and inaccuracies. It betrays a willingness to twist the scantiest scraps of information (the sale of a suit, for example) to fit and push a preconceived line of argument. The intent of the last two sentences of the quote is clear but sits oddly with the reality: John and Cecily were young lovers, preoccupied with each other, not an ideal time for clandestine meetings with the MVD or GRU and much less for indoctrination.

I had no difficulty getting information on Burton’s trip to Russia in 1939. Pamela Burton’s article mentions Burton’s own willingness to talk to researchers. It is the job of a responsible academic or researcher to look under every stone rather than to imaginatively fill missing gaps oneself. For every assertion Foot makes about Burton in his article, there is a valid alternative explanation that Foot either does not explore or dismisses in favour of his own prior predisposition. His focus is narrow. He ignores relevant material that would convey a very different picture of Burton from the one he seeks to promote.

__________________________________________________________________

Clive Edwards is an economist. He gained his PhD at ANU in 1965 and taught economics there until 1980. After a brief period in Federal government departments, he joined the School of Business at the University of Queensland in 1988. His main academic interests are in strategic management and international business with a focus on economic developments and business opportunities in East Asia. He was a member of John Burton’s extended family from the early 1960s.

This discussion is now closed. Our thanks to contributors.

Well, with all due respect to Francis, I don’t think I can take it any further. I can’t say, ‘honestly’, that Burton was a communist. I can’t ‘honestly’ say the evidence indicates that he was. All I can ‘honestly’ say is that my sense (or ‘feeling’)from the whole of the evidence I have examined is that it remains very much a live possibility. Further researches may confirm that sense, or they may refute it. Whichever way it might go, I will report it ‘honestly’. I don’t see how else an honest historian could be expected to proceed.

My thanks for a most stimulating discussion.

I thank Rob for his response, and of course the details.

However, again, Honest Feelings is not Honest History, and being neither prepared to go further than a ‘feeling’, or Professor Ball’s ‘probably’

I am reminded of the court room scene from The Castle in regards to the Constitution

“It’s Mabo, It’s Wik, Its just the vibe’ (sic…I might not remember this exactly, but readers will take my point”

A ‘feeling’, (and one so very hostile to any notion of Burton’s politics and philosophies, one that certainly dismisses all Burton’s work/ideas), is not the basis for an allegation of ‘treason’.

What would be Honest History is that Rob writes

“Why I think Burton was a Soviet Spy”.

This is not the same as it being ‘true’.

This should be clear, as Rob is very alone on this assessment.

Horner does not say it in the official history, neither do any of the other scholarly literature. Only Professor Ball has said anything like this.

If Horner did not put this front and centre of his History, but Rob does,

I leave to readers to decide where they will look for answers – Professor Horner or Quadrant.

Thank to Rob for this discussion.

All the best.

F

Thanks again to Francis for his response.

Despite Francis’ prodding, I am reluctant to go much further than saying my ‘feeling’ is that Burton was a communist. Certainly, officials in both Washington and London (including Ernest Bevin, no less) considered him to be at least a fellow-traveller. But he was not a party member. ASIO’s field officers consistently reported that while the CPA regarded Burton as a kindred spirit, and particularly useful on the Korea issue, he was not a member of the CPA. That seems likely. The MVD preferred where possible to work through agents who were not party members, as these could be assumed to be under suspicion or surveillance by their national security agencies. For this reason, the MVD instructed the Canberra Resident, Makharov, to be careful in his use of the spy network’s leader, Wally Clayton, who, as the CPA’s security chief, was too well known a communist to become engaged in any but the most important acquisitions. (That said, the MVD’s two principal agents in External Affairs, Milner and Hill, were in fact party members, although both were undercover members; that is, not known to members even to other members of the party. So the rule was not absolute. Interestingly, Burton knew that Milner was a communist.)

Rumour and reputation are one thing, though, and direct evidence is another. Unlike Francis, I think ‘The Alternative’ is clear evidence of a communist belief system, and it was assessed to be such at the time both by ASIO’s analysts and reviewers in the press. His propagandisinng for China and North Korea during the Korean War, his support for the communist journalist Wilfred Burchett, and his evident sincerity (according to ASIO) in doing so, suggest he was a conviction agent, not a mercenary or opportunist. Later in life, he showed himself no fan of democracy (see his article in ‘Dissent’, Spring 2004), preferring what seems to me (and I’m afraid I can put it no higher than that) a model of governance derived from the writings of the Marxist Antonin Gramsci.

None of which, though suggestive, is conclusive, so it leaves me with my ‘feeling’, rather than anything more concrete.

As to the identity of Burton’s controller, I agree with Professor Des Ball who has suggested it was probably Zaitsev, the GRU Resident in Canberra. Zaitsev was a senior GRU controller, who had run Richard Sorge, Moscow’s principal agent in Tokyo, until the latter was exposed and executed by the Japanese. Zaitsev was in Canberra from 1943 to 1947, and, as Prof Ball has argued, it is probable that such a senior GRU officer could only have been there for the purpose of running a very high value agent, namely Burton. Unfortunately, GRU communications were never decrypted (unlike the MVD messages exposed by the Venona project) so we have no means of verifying this proposition from Soviet sources.

I don’t find it surprising that Burton should never have disclosed that he was an agent. Ian Milner went to his grave in Prague denying he was an agent, but the Venona decrypts demonstrate unambiguously that he was.

I am not in a position to comment on Professor Horner’s ‘failure’ to conclude that Burton was an agent. Prof Horner is an eminent historian and his researches and conclusions are his own.

Could I express my thanks to HH for providing a platform for this important discussion.

I thank Rob for his response. I note his genuine co-operation and citing of digital collections too. I will return to these. I will make these comments and then leave it there.

Given the relationship between Quadrant, its original funding, its long standing associations (open and secret) with the intelligence community, and connections to the political hard right, it has a quite obvious and longstanding intellectual/political agenda of Quadrant

i.e. that all political persuasions to the left of itself (and that is quite the sweep of the proverbial broom) should do the noble thing by spontaneously combusting in perfect synchronicity, leaving the sensible people to run things properly.

But I just make this point, Quadrant is ‘not’ a scholarly journal, never has been, and is unlikely to be in the short or long term future. That is not its purpose, never has been.

If this is an area of ongoing scholarship worthy of examining, then Rob owes himself a detailed study to be published in perhaps Cold War Studies or a journal specializing in intelligence studies.

The collections Rob cited are well known (digitized). Much of the (not so recent anymore) MI5 material is also available.

On the points raised by Rob I just say this.

If Rob is seriously suggesting that he has have examined more detailed and ‘better’ material than Professor Horner (who claims full access to all ASIO files not released), then I think we might have to agree to disagree.

This material would have been enormous to say the least.

Horner would be well aware of the files Rob cited, they are public. (He did after all write a biography on Shedden) If there is basis for the claim made about Burton, and being an official history, Horner could have been backed to the hilt by ASIO and government.

He would have lost nothing. Burton had passed away. If ASIO cannot make (or support) the claim, or provide the material to Horner, and Horner is unable to even say whether Burton was even a communist, is there something seriously wrong with the Horner/ASIO collaboration?

Rob has a concrete idea and is unswerving in his assessments – how then could Horner have it so very wrong?

Or is the case that such a claim could not be supported by the ‘official’ history, but can be supported by Quadrant?

To my mind this is what is a problem.

Is Rob claiming that Professor Horner privately endorses his article?

Or that he left this all out of the official history, heavens why, with such access to ASIO material (particularly The Case), if it is so obvious, then this should have been a slam dunk (historically speaking).

If so, what is the motive for ASIO and Horner not putting in the publication what Rob argues is so obvious?

This is (for me) inexplicable.

I simply do not believe that Horner’s would do this. If Rob agrees with this assessment of Horner, then, why have Horner and Rob come to such differing assessments, and they are quite different.

I just make some observations. There were a wide range of individuals who became involved in the Friendship Society, (perhaps even a Minister of Religion and Pacifist or two). Many people in the period feared the breakdown of the wartime alliance, this was not unusual.

Being a member (or attending the activities) of a ‘front organisation’ does not necessarily mean what Rob suggests, if it did, then up until the mid-late 1960s, everyone who wrote or supported Quadrant must have been overt or covert members of the CIA – the CIA funded the Congress for Cultural Freedom – this organisation was set up to blatantly influence for the anti-communist cause with direct funding and cooperation from the CIA. This funding from the CIA was the only reason Quadrant could begin and then operate. https://jacketmagazine.com/12/pybus-quad.html

Would anyone suggest that everyone associated with Quadrant in that period was a US/CIA stooge? No. So why is it obvious about the Friendship society? There were many members, their motivations were complex. Were some communists, yes, these were open, but how does one judge the intellectual motivations of emerging peace activists (and others) through only the prism of Cold War anti-communism?

Very difficult.

Burton openly stated his philosophies, critiqued when it suited, did not adopt the Cold War line. The Alternative makes this discussion pretty bluntly.

I am glad that Rob has abandoned his claim that it made no difference to his thesis whether Burton was a communist or not, even from the earlier posts, it is clear.

The central point of Rob’s thesis is that Burton was a ‘communist’.

“Having subsequently also read Burton’s encomium to international communism (his 1954 pamphlet ‘The Alternative’) ……”

I find (and perhaps this is just where we differ) strange that Rob is saying he has only recently read this book, and because of having read it, and the Friendship society, have decided he was in fact a communist.

It seems clear (at least to me), that Burton being a communist is the central plank of Rob’s entire thesis all the way through. Far from not ever mattering, it is the very foundation.

Again (just my opinion) I find it very difficult to see that this book was a love note to communism, most see it as a stinging critique of 1950s Australian anti-communism particularly in its attitude toward Asia. Burton was certainly well out of step with the government and intelligence community of the period.

“I formed the view that he was, in fact, a communist – though he carefully refrained from ever admitting as much, almost certainly on instructions from his Soviet controllers.”

If Rob can name the Soviet controllers, or his handler in Australia, then that would greatly enhance his thesis. They must have met, there must be records of such an obvious relationship?

Instead what we have is Spry (Burton is not a communist), Petrov (Does not name either Burton or Evatt), Horner (fails to write anything remotely – my assessment – similar to what Rob has written about Burton).

The idea that Burton never admitted anything out of loyalty to the USSR (which ceased to be in 1991), under instructions of his handler, is interesting. He remained silent for the entirety of his life and he lived into his 90s. So Rob suggests that Burton was a communist ‘sleeper agent’ throughout his subsequent academic career, retirement, and even past the end of the Soviet Union itself.

That he told no one, not a soul, no one, even after 1991?

There is of course another very strong historical assessment, Burton was not a communist, did not have a handler etc.

Yet we have what exactly, two known documents (UK) leaked to Moscow. This was hardly a secret at the time (or shortly afterwards) as Frank Cain’s work has highlighted long ago.

As for the experiences of MI5, this was an organisation with ‘British’ KGB moles at the very heart of its operations and they had little idea, or ability to weed them out. If there was any major weak link in the intelligence community it was not in Canberra, it was in London (or in the US itself as it turns out).

There is also the Spy Catcher thesis that Hollis was the KGB kingpin who got away with it – Rob is well aware that Hollis was deeply involved in advising the setup of ASIO itself.

I make no judgement on Hollis, honestly, I do not know (this is just the Spy Catcher thesis), however, does anyone seriously suggest that the Soviets did not use their sources in the UK and the US to find out all manner of information, but instead they relied on Burton to shift the balance of world power from Canberra (they got two known documents (45-49) and The Alternative in 1954?

“As Francis says, why would someone spy for the USSR if he/she were not a communist? My feeling, now, is that Burton was, and that is why he did it.”

I see no evidence for this, but I note that it is a ‘feeling’ – obviously Rob does not like Burton’s politics or style, however this does not make him a communist. Spry certainly did not share Burton’s politics, yet he did not seem to think him a communist. Spry saw communists everywhere, had the strictest watching briefs, how could Burton evade all this?

If Rob can offer a corrective to Horner’s official history (which certainly does not say what Rob says on this forum or his article, no matter what Horner was asked at his book launch) and uncover what he asserts (Burton’s party membership, his Soviet handler, and documents (outside of the well-publicized British reports x 2), explain how his ‘handler’ forced Burton to stay silent beyond the end of the USSR etc., then Rob will no doubt enjoy (and should enjoy) many prestigious journal articles and a major scholarly monograph outlining his research.

If this comes to being, then all historians of Australian political and diplomatic history will owe Rob a deep seated expression of thanks (myself included), for he will have single handed re-written the Australian Cold War from the late 40s into the 50s.

I would be the first in line to offer my hand in sincere apologies for these (genuine scholarly) criticisms.

But if we are only left with digitized files from ASIO (not the most reliable in my opinion), and Defence (Shedden deeply disliked Burton and Evatt) long available to the public, the MI5 files, a few articles in Quadrant, or a book from Quadrant publishing (in the vein of the articles), then this is little more than what has been asserted on this forum, ‘a feeling’.

History, robust, critical, even controversial history is based on deep evidence, it is not a series of subjective assertions. I have no issue of Rob saying what he says, or holding whatever view he wishes, but an opinion or ‘feeling’ is not a ‘fact’.

If we want Honest Feelings, then fine, Rob says that Burton was a communist.

But if we want Honest History, then the standard for the accuser should be (as I have highlighted here) should more rigorous.

My thanks to Francis for his considered comments. I think I can walk past the snark about Quadrant and get to the genuine issues he has raised.

First, Professor Horner’s Volume 1 of the official history of ASIO. Prof Horner was asked, at the launch of the book, about allegations concerning Burton. He made a specific reference to my 2013 Quadrant essay, and noted that he had only examined ASIO’s own records, but that the Q article indicated there was much room for further research. (He did not contest the essay’s judgements.)

Prof Horner was quite right. My essay was not only based on declassified ASIO records, but also those of the Department of Defence (which in my view are the truly critical ones), and also many files recently declassified and released to the British National Archives by MI5. There is a wealth of relevant material in the TNA at Kew which I have not yet examined.

The 2013 essay was extensively footnoted, and I am afraid that if Francis wants these citations he will have to get them from Quadrant. As I understand it, the magazine now owns that content and it is up to the magazine how it is to be released. I can advise Francis, however, that the relevant ASIO files are in the A6119 series at the NAA, and the Defence files are in the A5984 series (‘the Shedden collection’). Most of the relevant files have been digitised and are available online.

Francis’ point about Burton being a communist is relevant. It is true that the Director-General of Security, Charles Spry, did not consider Burton to be such, and in fact he once reprimanded one of his field officers for having described Burton as ‘a suspected communist or associate of communists’ in a surveillance report. And in an earlier comment I said that it was no part of my argument that Burton was a communist.

I am no longer so sure. In a subsequent Quadrant piece (October 2015), I reported something I had not earlier known, and of which Spry was unaware – that Burton had been a member of the Anglo-Soviet Friendship Society probably from 1938 until late 1948, when he was ordered by his Minister, Evatt, to resign because his continued membership would be politically damaging. Few people other than overt or covert communists would have joined such an obvious ‘front’ organisation.

Having subsequently also read Burton’s encomium to international communism (his 1954 pamphlet ‘The Alternative’), I formed the view that he was, in fact, a communist – though he carefully refrained from ever admitting as much, almost certainly on instructions from his Soviet controllers.

As Francis says, why would someone spy for the USSR if he/she were not a communist? My feeling, now, is that Burton was, and that is why he did it.

Finally, there is no reason to think that ASIO’s files on Burton reflect anything other than the considered judgments of Australia’s counter-intelligence professionals. However, unlike their British counterparts (who had much greater experience in such things), they never openly opined that Burton was most likely an agent for the Soviet Union, although their colleagues in Defence had voiced such suspicions as early as the late 1940s. Those conclusions were not ASIO’s, but mine.

Although I am sure Rob is correct (after all not only does he say so very clearly, as we are all aware, Quadrant is known for its objective disinterested scholarly analysis, Windshuttle’s article on the ‘extermination’ of the ‘Queensland Pygmies’ by Qld. Aborigines being a particular favourite of mine),

however I do wonder…….

Rob argues it is either Soviet spy, or an idiot. Just two explanations!

Just two ummm.

Neither one favourable, both worthy of Rob’s obviously justified contempt.

Pure scholarship, no irrational confirmation bias at work, just objectivity at its finest?

I wonder, given that Professor David Horner (not a noted member of the Australian Left), was commissioned to write the ‘official history’, and claims to have had complete access to all historical ASIO information (which is certainly far more access than Rob seems to have), he not only does not uncover Burton’s treachery and treason, not only fails to unmask the evil Burton at work, he comes to the conclusion that he was not even a ‘communist’.

Is Rob suggesting that Horner, with his much greater access to the ASIO basement of secrets including ‘The Case’, has missed what is so obvious to Rob and his NAA referenced materials?

How could that be?

Would ASIO withhold such information from Horner, would Horner censor such information out of his ‘official history’?

Or is it just possible (however remote), that the basis for such allegations (evidence) was not in the files examined by Horner for his ASIO book?

I find it hard to imagine that ASIO would withhold anything of that nature on ‘The Case’ particularly if it implicated someone like Burton, I find it impossible to accept that Horner would omit any such information from any official history if there was legitimate evidence (other than hear say) to back up such a conclusion.

Horner would never do such a thing. So why does Rob maintain that he is correct and that Horner (by implication) has missed what is so obvious? Is Rob a better historian of this story than Horner?

So how do Rob and Horner come to rather different conclusions given the greater access granted to Horner?

I do wonder Rob, if one is not a ‘communist'(Horner on Burton), what other motivation is there to clandestinely ‘work’ for the USSR? You cite one document that was leaked. Where are all the rest of materials that Burton must of had access and leaked, there must be so many. It would be helpful if you can name them in order of significance. This way we can get a clearer picture of this ‘treason’?

Far from denigrating Rob’s work in a publication like Quadrant (a publication never influenced by any pre-existing political agendas), he does allude to NAA materials.

But given that this is Honest History Rob, could you provide the NAA references to the statements made in your above post? I would be most interested (as would others) to compare them to the sorts of materials cited by Horner. I doubt I will read your article in its entirety,particularly if it requires purchasing a Quadrant product, and as you have kindly outlined your main points above, the references would be helpful.

I think that would be very useful for a debate on an issue like this (and on a site like Honest History), to know if Rob is using de-classified ASIO files from the Burton and post-Burton period held by the NAA.

ASIO files (particularly from the 50s, 60s) are hardly the most reliable records of our historical past. But if I wanted to write a hit piece on Burton, leveling each and every allegation with a NAA reference, that is where I would go.

There should be an opening quotation mark before the word constituted. My apologies.

A corrective to Mr Cocks. Page 304 of Horner’s excellent account does not reveal Spry holding that Burton was not a Soviet agent. It shows Spry averring that he was not a communist. It is no part of my argument that he was.

Spry did, however, consider Burton to be a security risk. After an examination by ASIO of Burton’s 1954 book ‘The Alternative” revealed that Burton had included confidential information derived from his time as Secretary of External Affairs, Spry in February 1955 informed the Secretary of the Prime Minister’s Department that there would be a security risk to he Commonwealth if Burton were given access to Secret or Top Secret information. This was in the context of Burton being, at that time, in contention for a position on Dr Evatt’s staff. It was agreed by the then Secretary of External Affairs and the Solicitor-General that certain passages in the book constituted a serious misuse of information obtained officially’.

The original article in Quadrant is accessible only by Quadrant subscribers. We did not link it to either the reference post for the original article by Pamela Burton or this one by Clive Edwards. The reference was given for those who wished to track it down. We have now added the link in both these reference posts. David Stephens, Senior Website Writer, HH

Mr Cocks will find every claim is foot-noted as to source (usually records in the National Archives) if he consults the original article in Quadrant.

While we all have our prejudices, and must guard against them, anyone claiming to describe and interpret past events must, if they want to be taken seriously, document and reference their sources. Unfortunately, Mr Foot, in writing about Dr John Burton, seems to have drunk from the same deeply secret well as Professor Desmond Ball. Given clear statements from informed insiders such as Dr David Horner and Col. Charles Spry (see Horner’s ‘The Spy Catchers: The Official History of ASIO 1949-1963’, p.304) that there is no evidence that Burton was a Soviet agent, (on the contrary), the onus is on Mr Foot to prove his case. For example, baldly saying ‘Spry was wrong’ is evidence of nothing other than Mr Foot’s starting position. If Mr Foot wants to keep trying to make people believe that he is not flogging a dead horse, he must do better.

Doug Cocks

I don’t think Clive Edwards’ characterisation of my piece in Quadrant could really be said to have been an honest account, so perhaps I could straighten things out for the benefit of your readers. It’s a tangled skein, to be sure, but the key sequence – and there are many others – which points to Dr Burton’s complicity in espionage, put briefly, is as follows:

• Sometime between November 1945 and January 1946 Dr Burton, whilst acting as Secretary of External Affairs, discovered that one of the Department’s senior officers, Ian Milner, had taken a UK Planning Paper of the highest security classification out of the office for the weekend.

• This was an extremely serious breach of security, as the document had been provided by the UK on conditions of strictest secrecy, and should never have been removed from secure government premises without official permission.

• Dr Burton did not report this security breach to anyone, nor (as far as can be determined) was it the subject of any formal record. He was the ultimate administrative authority in the department at that time. Milner was not reprimanded and he continued to have unrestricted access to highly classified information.

• Two years later, Dr Burton learned that the Planning Paper in question had been passed to the Soviet intelligence service at the time that Milner was in possession of it. He therefore knew that what might have been viewed as a casual security breach had in fact been a calculated act of espionage.

• Dr Burton immediately informed the Soviets that the British had detected the leakage of the Planning Paper, thereby revealing the deepest secret of the western intelligence alliance – that the Soviet cyphers had been broken. (Word of the paper’s acquisition, and its text, had been sent to Moscow only by encrypted cable.)

• The Soviets changed their cyphers soon afterwards, and communications between Canberra and Moscow became unreadable. This meant that the flow of intelligence about Soviet espionage against Australia was abruptly terminated.

• According to later investigations by both External Affairs and ASIO, Dr Burton made no attempt to investigate the leakage, but instead sought to shift responsibility onto the Service Departments (which he knew had had no access to the document in question).

• Despite the breach he had detected two years earlier, Dr Burton advised the government that Milner was completely trustworthy, and would not have mishandled any secret information to which he had access. He made no attempt to question Milner, although he could easily have done so through his own department’s representative in New York (Milner was by then working in one of the UN’s secretariats).

• Burton’s report formed the basis of the Australian Prime Minister’s letter to his British counterpart, explicitly clearing Milner of any suspicion (although acknowledging he had been in possession of the leaked paper).

• Neither Burton nor Chifley was aware that it was the US intelligence service which had detected the leakage, rather than the British.

• Chifley’s letter, together with earlier sources of US dissatisfaction with Australia’s security, caused the US to impose a total embargo on sharing classified information of US origin with Australia. This had a crippling effect on Australia’s defence capability. The embargo remained in place until after the change of government in December 1949.

• As a consequence, the US reduced the level of Australia’s trustworthiness to the same level as that accorded the Soviet Union. In other words, Australia was now rated as an enemy of the west in the eyes of the United States (by then the acknowledged leader of the free world). This was at a time when a global war between communist states and the west was thought to be in serious prospect.

That is the core of it. In seeking to understand Burton’s actions, as described above, there are only two likely explanations: either he was extraordinarily reckless, foolish and naïve; or he was working for the Soviets. Hence the sub-title of my article: ‘Soviet Agent or Useful Idiot?’ I lean strongly toward the former explanation, of course, but I concede the latter is not impossible.