‘Complex stories of the Djadja Wurrung in Victoria’s Good Country’, Honest History, 30 January 2018

Ben Wilkie reviews Bain Attwood’s The Good Country: The Djadja Wurrung, the Settlers, and the Protectors.

Bain Attwood’s most recent book appears, at first blush, to be a humble undertaking. It is, at the highest level of description, a history of the Djadja Wurrung people of central Victoria and their experience of British colonisation. This history of Indigenous-settler relations is, however – to echo its central historiographical claim – a bit more complicated than that.

Attwood has set out to write the story of the three-way interactions between the Djadja Wurrung, the settlers who invaded their country, and the officials who were appointed by the imperial and colonial governments to protect the Aboriginal people. Attwood also seeks to illuminate the relationships between the Djadja Wurrung and other Aboriginal groups in the area, including the Daung Wurrung. ‘For too long we have tended to conceive of our histories of colonisation in terms of just two groups – the whites and the Aborigines’, writes Attwood in his introductory remarks, ‘which is a result of our projecting onto the past racial categories that barely existed or were only in the process of being forged at the time we are investigating’.

Attwood has set out to write the story of the three-way interactions between the Djadja Wurrung, the settlers who invaded their country, and the officials who were appointed by the imperial and colonial governments to protect the Aboriginal people. Attwood also seeks to illuminate the relationships between the Djadja Wurrung and other Aboriginal groups in the area, including the Daung Wurrung. ‘For too long we have tended to conceive of our histories of colonisation in terms of just two groups – the whites and the Aborigines’, writes Attwood in his introductory remarks, ‘which is a result of our projecting onto the past racial categories that barely existed or were only in the process of being forged at the time we are investigating’.

This is a foretaste of the kind of history Attwood writes. In The Good Country he sets out with a set of well-defined convictions about how Aboriginal history has been written and proceeds to examine the experience of the Djadja Wurrung and how it should be set down. Attwood seeks a form of history-making that centres Aboriginal people and Aboriginal points of view in history, and emphasises the ‘survival of an autonomous indigenous world’, rather than telling a story purely of destruction and dispossession.

Furthermore, as is evident in the purposefully limited scope of The Good Country, Attwood aims for a focus on the ‘aboriginal’ in the sense of the local: ‘Although doubt has been cast on the validity and usefulness of national historiography itself’, wrote Aboriginal History journal founder Bob Reece in 1987, ‘there still seems to be a naïve need to generalise about “the Australian experience”’.

Moreover, Attwood shares with the founders of Aboriginal History a conviction that the histories of Indigenous-settler relations were significantly more complicated and various than have been encapsulated by the dominant concepts of, for example, the Frontier, conflict, and resistance, which still act as broad guiding principles in both academic and popular narratives of the history of the British colonisation of Australia. In short, writes Attwood, ‘there were a range of ways in which the colonised and coloniser related to one another’. The Djadja Wurrung were, as The Good Country reveals, not simply passive victims, but sought variously to adapt, accept, resist, or take refuge.

Attwood is, by and large, able to apply this model of historical research and discourse to the case of the Djadja Wurrung because the invasion of their country essentially occurred at the same time that the British government established an institution that was given the responsibility to protect the Aboriginal people of the Port Phillip District of New South Wales. There is, therefore, an unusually rich documentary record for interactions between British colonisers and the Djadja Wurrung people, although this means – as is so often the case – a heavy reliance on settler perspectives.

Chief among these voices in The Good Country are Chief Protector George Augustus Robinson and Assistant Protector Edward Parker, whose accounts give detailed insights into the ways in which the invasion of Djadja Wurrung country proceeded, through first contacts and conflict, to frustrated attempts at protection and refuge, to the abolition of the Port Phillip Protectorate and the removal of the Djadja Wurrung to Coranderrk – and, it was assumed at the time, the end of the Djadja Wurrung community.

Although The Good Country is, ostensibly, a local history, concerned with a relatively small set of individuals and acting within clearly defined spatial and temporal limits, Attwood is well-attuned to the contemporary political implications of his work. In 2013, the Victorian government and the Dja Dja Wurrung Clans Aboriginal Corporation reached an agreement that formally recognised the Djadja Wurrung as the traditional owners of their land in central Victoria. The agreement granted freehold title to two properties of particular cultural and historical significance and transferred two national parks, one regional park, two state parks and one reserve to Aboriginal title. The agreement also provided significant funding for the advancement of Djadja Wurrung cultural and economic goals.

Such settlements between Australian governments and Aboriginal claimants to native title, Attwood reminds us, are an outcome of the gradual rise of the Aboriginal rights movement in the post-war era – rights for Aboriginal people, as both the descendants of the original peoples of the country and as peoples who had suffered enormously because of British colonisation. These were essentially historical claims, provoking an Aboriginal history movement that emerged to meet the needs of Aboriginal people: family histories and genealogies; ethnographic accounts of traditional culture; histories of resistance and histories of dispossession. Attwood writes that ‘Aboriginal people’s demands for Aboriginal rights and the manner in which the Australian state responded to these have led to a certain kind of history being produced so that both parties are able to realise their various economic, cultural and political goals’.

This form of history-making, argues Attwood, has stressed cultural difference and tradition and has emphasised, in response to native title legislation, continuous links with traditional culture. Furthermore, ‘claimants produce histories that stress on the one hand the overwhelming power of the settler state and settler peoples, and their dispossession, destruction and displacement of Aboriginal people and culture, and hence their responsibility for what has happened and their obligation to provide redress’, but also Aboriginal people’s resistance, ‘including, most importantly, their maintenance of tradition’.

Drawing on the example of claims made at the announcement of the recognition and settlement agreement between the Dja Dja Wurrung Clans Aboriginal Coporation and the Victorian government, and the adjacent case of the repatriation of Djadja Wurrung artefacts from British museums, Attwood points to significant conflicts between history of the kind that supports assertions made by the Aboriginal rights movement and meets demands laid out by the Australian state, and, on the other hand, history of the sort produced in universities and museums.

Aboriginal farmers, Loddon Aboriginal Protectorate, Franklinford (Djadja Wurrung country), 1858 (Wikipedia/Fauchery-Daintree Collection)

Aboriginal farmers, Loddon Aboriginal Protectorate, Franklinford (Djadja Wurrung country), 1858 (Wikipedia/Fauchery-Daintree Collection)

This conflict has been helpfully theorised by Dipesh Chakrabarty in terms of subaltern pasts and minority histories, which do not necessarily ‘conform to the protocols demanded by the discipline of history or meet the conditions for rationality that are demanded by it and the democratic nation state it serves’. Such subaltern voices have, consequently, been assigned an inferior position in historical discourse. Furthermore, critics have tended to exaggerate the extent to which paying heed to these narratives would ‘lead to an outbreak of what they regard as hapless relativism or postmodern irrationalism’.

In the early 1990s, the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation sought to bring together traditional views of Australian history with Indigenous histories. This was a project Attwood refers to as ‘shared history’, which, he writes, ‘largely conceives of history as a body of historical facts presented as a singular story compiled by an anonymous narrator’. In his closing remarks, Attwood puts forward a compelling argument for ‘sharing histories’:

[S]haring history tends to regard history as a collection of narratives told by differently situated or positioned peoples and hence contingent on who the teller is, what their purpose is, the context in which they tell their story, and who their audience is. In conceiving of history in this way, sharing histories highlights the conjunction between past and present as the ground upon which all history-making occurs.

Attwood argues that recognising that historical knowledge is a matter of perspective is not a relativist position, but simply the acknowledgement that ‘the most significant parts of historical narratives are always contingent, limited and partial’. This approach to reconciling the history-making of colonised and coloniser, suggests Attwood,

assumes that democracies such as Australia will continue to be peopled by groups with diverse histories and identities, presumes that there will continue to be contestation and conflict … Most importantly [sharing histories] would allow for different forms of historical knowledge, thereby providing for a measure of equality between academic history and Aboriginal ways of relating to the past.

What Attwood suggests, therefore, is that we move away from attempts to build a monolithic national narrative that all of us can agree upon, for these attempts have been shown to be futile in all of their guises. Instead, history-making itself should be seen as an act of cross-cultural communication.

Furthermore, transcending the limitations of national historiography need not push us to look across national borders into transnational or comparative history. Instead, such a project might be more successful with a renewed focus on spatial and temporal specificity and contingency, and an openness to complexity and ‘messiness’ grounded in archival research as opposed to the tendency toward the highly conceptual and programmatic historical reflections on ‘the Australian experience’. The Good Country attempts to model these approaches, and succeeds as both an intimate, local history of the Djadja Wurrung, the settlers, and the protectors, and as an urgent, timely, and provocative comment on some of the key debates around Australian history that linger on in the public sphere today.

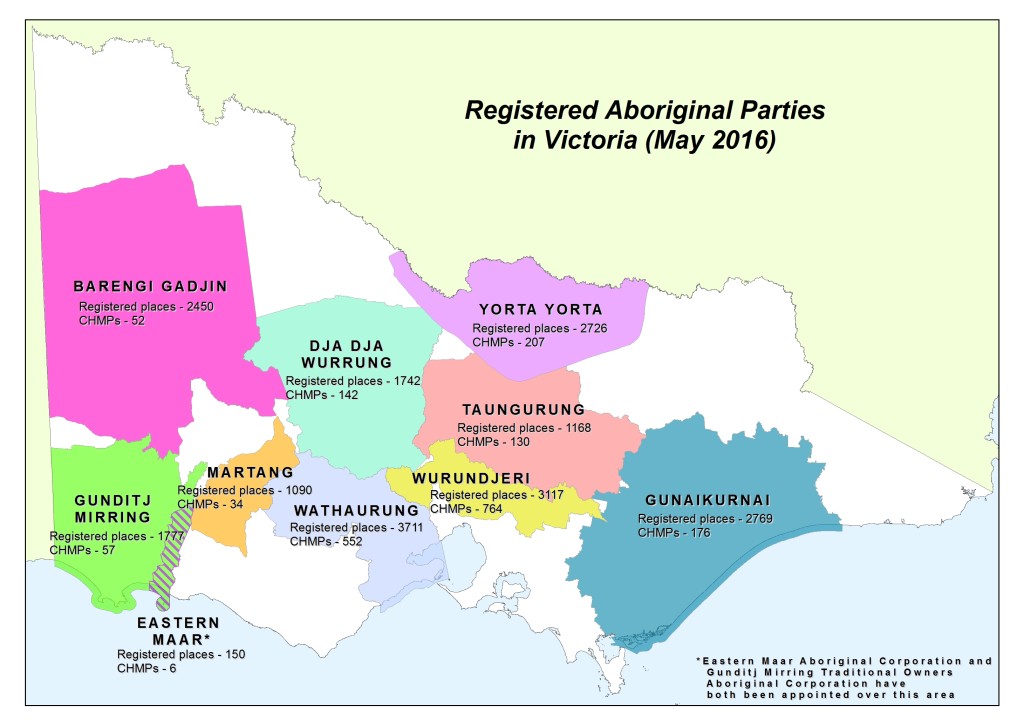

Registered Aboriginal Parties under the Aboriginal Heritage Act (Vic.) 2006 (maggolee.orasy)

Registered Aboriginal Parties under the Aboriginal Heritage Act (Vic.) 2006 (maggolee.orasy)

* Ben Wilkie is an Honorary Fellow at Deakin University, Victoria. His first book is The Scots in Australia 1788-1938 (2017) and he is currently writing The Grampians: History & Nature. He writes on Australian arts, culture, and politics for a variety of publications.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.