‘Wilfred Burchett recalled by Rupert Lockwood: highlights reel (I)’, Honest History, 1 September 2015

Recently we ran Wilfred Burchett’s famous report of the immediate aftermath of the bombing of Hiroshima. That post included some links to material on this enigmatic Australian (born 1911, died 1983) and wandering citizen of the world.

This time we present some highlights from a long, undated (but circa 1994) essay by Rupert Lockwood (1908-97), another Australian internationalist, in which he reminiscences about Burchett in Moscow in the 1960s. There is more on Lockwood in a recently completed thesis by Rowan Cahill. The thesis has a full bibliography.

Burchett (like Lockwood, for that matter) provoked strong feelings while he was alive and probably still does. One of the interesting aspects of Lockwood’s article is that he seems to have few illusions about Burchett, taking him ‘for all in all’, while bringing out his human side and the trying aspects of his exile outside of Australia. Given current policies towards Australian citizenship and its privileges, Burchett’s status as an Australian denied a passport is worth pondering.

The extracts here – more next time – are taken from the version of Lockwood’s article reproduced by Rowan Cahill on his Radical Sydney blog. Phillip Deery also put an edited version up in the Labour History Society’s Recorder. There is also a longer version lodged in the National Library of Australia. Honest History thanks Rupert Lockwood’s daughter, Penny, for bringing this material to its attention and for her help. The ‘opening scene’ in the article took place just 50 years ago this month.

_______________________________

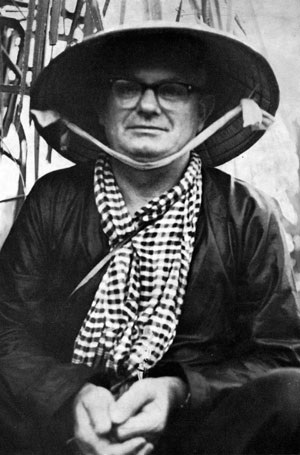

Wilfred Burchett c. 1960s (Radical Sydney)

Wilfred Burchett c. 1960s (Radical Sydney)

Rupert Lockwood’s article opens in September 1965 as Burchett rushes around, simultaneously hosting a farewell party and trying to obtain the paperwork he needs to get out of Moscow ahead of the ministrations of a disapproving communist regime.

Wilfred’s guests gave him an ironic cheer [when the visas came through]. They included writers, actors, scientists, university professors and Foreign Office officials prepared to take the risk. They knew Wilfred was being “unpersonned”.

Whatever had Wilfred done to incur Soviet wrath? The Stalin witch-hunters would have found nothing to criticize in his writings on Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union. His book, People’s Democracies (1951), was one of the most outrageous historical distortions in a field where competition was severe. The carefully detailed conspiracy web in which Hungarian Foreign Minister Lazlo Rajk and Yugoslavia’s Tito were alleged to be key operatives, as faithfully portrayed by Wilfred in his report on the Budapest trial, demoted John Le Carre and Ian Fleming to Boys’ Own Paper class. Rajk, he related, “worked all over Europe as a police spy – for Yugoslav, British and Franco Spanish Intelligence, for the Gestapo and the CIA”.

Rajk had in fact fought in the International Brigade in Spain and been gaoled by the Fascist Horthy regime in Hungary but ‘Wilfred, like so many sympathizers with the new order in Eastern Europe, believed the perjured evidence extracted under torture’. He also mistakenly accepted Stalinist denunciations of Bulgarian Deputy Premier, Traicho Kostov.

How could intelligent and seasoned reporters like Wilfred Burchett and the vast majority of Communists abroad – including myself – have fallen for it? The Soviet Union had great prestige as the first country to introduce what was regarded as “socialism”, and as the main contributor to victory over Hitlerism. The Soviet Union’s wartime performance, as reported around the world, tended to confirm the achievements claimed in economic and social spheres. Who on the Left could at that stage have believed that for the USSR leaders outrageous lying, torture of innocents, frame-ups, deceit and fakery were the general rule? That statisticians who gave accurate figures on the Soviet economy were being shot? The Stalin censorship was one of the most effective in all history.

Burchett tried to apologise to the relatives of Rajk and Kostov and this, along with other publicly expressed doubts and the work of informers, helped, says Lockwood, to bring Burchett under the suspicious eyes of the KGB. Czech intelligence operatives and Greek communists also had him down as an American agent. He began to find China, North Korea and Vietnam more congenial. Nor did Burchett have much time for Khrushchev, the former ardent Stalinist, now anti-Stalinist.

Khrushchev had further reduced his standing for Burchett by giving Ekaterina Furtseva, Minister for Culture and allegedly Khrushchev’s lady friend, a pat on the bottom as she ascended the saluting base in Red Square. Russians who saw it live on TV were scandalised.

Burchett had married Vessa, a Bulgarian.

Marriage may have provided another entry in Burchett’s KGB dossier. Vessa worked in the Bulgarian Foreign Office, then little more than an annexe of the Soviet Foreign Office. A notice appeared on the office board, denouncing Vessa for ideological deviations and faulty work. In those hair-trigger days the pasted-up denunciation could have led to a sentence to a “strict regime” labour camp. She was quickly in touch with Wilfred. He made firm representations to surviving contacts in Sofia and Moscow. His pleas – and marriage to Vessa – saved her.

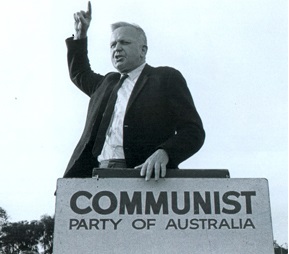

Rupert Lockwood, 1963 (Radical Sydney)

Rupert Lockwood, 1963 (Radical Sydney)

The Burchetts lived in a well-appointed (but not KGB-supplied) Moscow apartment, which Lockwood and his family took over after the Burchetts’ hasty departure for Phnom Penh. Lockwood had arrived in Moscow in April, 1965, as the new Moscow correspondent for the Australian communist newspaper, Tribune. One of his predecessors, Rex Chiplin, had returned to Australia with mixed feelings about his time in Soviet Russia.

[He] got off the plane at Kingsford Smith Airport, took a taxi to the Communist Party headquarters then in Market Street, Sydney, and shouted at a Central Committee functionary, as he flung his party membership card down on the table, “If that’s socialism, you can shove it up your arse!”

The Lockwoods’ (formerly the Burchetts’) apartment had a great view, as Rupert Lockwood recalled:

The greatest joy on entering the Burchett apartment was a view I thought was without equal in the world. The scene outside of the Moscow River and the Kremlin was so distractingly enchanting that I often could not do much work. Why ever would Wilfred swap all this for a modest pad in Phnom Penh?

Next time: Burchett and Lockwood both caught in the middle, a Burchett accounting – and one joke. We’ll also add some more links to material on both men.

A view from the Lockwoods’ apartment, 1966, with Kremlin in distance (Penny Lockwood)

A view from the Lockwoods’ apartment, 1966, with Kremlin in distance (Penny Lockwood)

Few people are aware that Wilfred Burchett was – like a surprising number of influential international journalists – also a key go-between East and West, especially during the latter stages of the Cold War.

He played a significant – but virtually concealed – role in helping US and Chinese governments make contact. This eventually led to Richard Nixon’s visit to China and official recognition of the People’s Republic of China as the official representative of the Chinese people at the UN.

Such ‘go-betweens’ have always existed and are essential, especially during wars. These individuals are usually people with considerable influence and wide political and government connections and contacts who – although expressing their own strongly-held views – are usually trusted by both sides

Burchett’s last ‘public’ appearance was accidentally exposed when he was spotted in New York at a ‘secret’ breakfast meeting with Henry Kissinger. This exposure caused a brief uproar that was very rapidly quelled and all further media reports and comments disappeared almost overnight.

After all, John Foster Dulles brother Allan Dulles – who spent most of WW2 in Switzerland – was a similar ‘trusted go-between’ with strong Right-wing views who maintained contacts with the Nazi Regime on behalf of the Allies – especially the US government.

The true story of Wilfred Burchett has still to be revealed. He was never a traitor, just a well-informed idealist who fully understood realpolitik