Peter Stanley

‘”Who are the liars?” A response to Hal Colebatch’s Australia’s Secret War’, Honest History, 17 December 2014

Hal Colebatch asks in Quadrant Online, ‘So, Professor Stanley, Who Are the Liars?’ Er, no one, I answer. Who says that anyone’s lying? I claim instead that Dr Colebatch has written a book that presents an unjustified picture of the role of unions in Australia in World War II, one which is badly written and – most crucially – misreads or misuses evidence. But I’ve never accused him or his informants of lying. And I hope that he wouldn’t describe me as a liar.

In response to my critique of his book on the ABC’s website The Drum Dr Colebatch wrote to me: ‘read my challenge in Quadrant Online and reply if you dare!’ Well, I dare: here it is. (I assumed that Hal Colebatch and Quadrant Online having invited the response, as it were, Quadrant Online might publish it; in fact its editor, Roger Franklin, declined to reply to my email.*)

In response to my critique of his book on the ABC’s website The Drum Dr Colebatch wrote to me: ‘read my challenge in Quadrant Online and reply if you dare!’ Well, I dare: here it is. (I assumed that Hal Colebatch and Quadrant Online having invited the response, as it were, Quadrant Online might publish it; in fact its editor, Roger Franklin, declined to reply to my email.*)

Having worked my way through Colebatch’s book Australia’s Secret War (sub-titled on the cover ‘How unionists sabotaged our troops in World War II’) I am even more certain that this is a book that does not deserve to jointly win the Prime Minister’s Prize for Australian History.

Before I turn to a more detailed critique of the book, but since Quadrant Online’s editor, Roger Franklin, brings it up, my criticism is not retribution for the various articles published in Quadrant in which I am linked with other historians regarded as mounting an ‘Assault on Anzac’. (For example, in February this year, June 2009 and July-August 2009.) The list of academics and others supposedly inimical to the Anzac legend and criticised by Mervyn Bendle besides me includes Joan Beaumont, Anthony Burke, Adrian Caesar, Martin Crotty, Joy Damousi, Peter Dennis, Ashley Ekins, Robin Gerster, Jeff Grey, Jeff Hopkins-Weise, David Horner, Marilyn Lake, Peter Londey, Mark McKenna, Andrew Moore, Robin Prior, Henry Reynolds, Craig Stockings, Alistair Thomson and Stuart Ward.

Like me, many of these scholars take a perverse pride in having been ‘Bendled’ – we must be doing something right to be criticised in such company – though I have to say that this is such a diverse group, straddling world-class scholars and virtual amateurs, employed and retired, post-modernists and traditionalists, old and young, left and right, that it is meaningless to lump them together. This is no anti-Anzac conspiracy: not only do some of these people not agree with each other, some do not even talk to each other.

(And while I have the chance, I can assure Dr Bendle that criticism of my views on the so-called ‘Battle for Australia’, by among others John Howard and Kim Beazley, had nothing to do with my departure from the position of the Australian War Memorial’s Principal Historian in 2007. Towards the end of my tenure at the Memorial the then Director, Major General Steve Gower, and I did not always see eye-to-eye. But we never differed in our view that the idea of the ‘Battle for Australia’ was a revisionist beat-up, unsupported by historical evidence or reasoning, and Steve Gower supported me voicing my opinion, which I expressed in the Memorial’s annual Oration a month or so before I resigned from his staff.)

I recently said (in response to a question from Mike Seccombe of The Saturday Paper) that ‘good history has to be based on evidence, scholarship and good writing’. I thought that ‘Hal Colebatch’s book fails on every one of those measures’. Let’s start with the writing. For a book written by a man known as a poet, Australia’s Secret War is strikingly badly written. It resembles nothing so much as music by Michael Nyman, the composer of monotonous scores for films such as The Piano or The Draughtsman’s Contract: for a while interesting, but soon wearying by repetition. Typically, Colebatch introduces a former World War II serviceman, whom he interviewed or corresponded with in the mid-1990s. The man recounts an incident where their ship or unit was supposedly impeded by industrial action and Colebatch comments on how outrageous this all was. None of this demands much artistry by Colebatch. He typically quotes great slabs of a letter or a memoir, sometimes placing the ship or the unit in its wartime context by reminding readers of actions in which it served, but more usually simply retailing one story after another, with the stories resembling each other and – this is most important – Colebatch never even trying to corroborate or document the claim.

Colebatch is quite bad on detail, repeatedly getting names or titles wrong: there was no such unit as ‘First Australian Corps of Signals’; no ‘7th Battalion’ in the 7th Australian Division (but there was a 2/7th in the 6th, a 2/27th in the 7th, and a 2/17th in the 9th: which was it?); no RAAF ‘467 Transport Squadron’ – Colebatch misunderstood that a man served in 467 Bomber Squadron in Britain and then came home to serve in an (unnamed) transport unit. And so on. These are minor errors: but Colebatch didn’t check even though he had years to hone the manuscript while he shopped it around the publishers who rejected it. In passing, it should be said that this gives the book a curious dated quality – the most recent ALP figure with whom Colebatch jousts is Paul Keating, who was Prime Minister presumably when Colebatch was writing the book, nearly 20 years ago. The book’s references are out of date: for example, Colebatch repeats the discredited belief that Japanese ‘invasion money’ (banknotes) somehow supports the idea that the Japanese planned an invasion; he is years behind the game.

A clunky writing style and errors of detail are aggravating but not vital. More worrisome is the substance of the book: Colebatch’s allegations that union obstruction seriously impeded Australian military operations. These allegations are usually couched as vague claims that ships sailed late, supplies were short: deplorable allegations, if true, but essentially un-checkable. When he gives details, however, his claims turn out to be either impossible or unlikely. Let’s consider three instances from the opening chapters, in which Colebatch claims that unionists adversely affected the battle of Milne Bay, the guerilla fighting on Timor and the planned rescue of the Sandakan prisoners of war.

Colebatch claims that, had wharfies been less tardy in loading 155 mm guns destined for Milne Bay, the guns ‘could have destroyed the Japanese landing forces before they got ashore’ (p. 13). Perhaps. But Colebatch says that the guns were ordered to be loaded only on 5 September 1942. The Japanese had landed ten days before this. Even if the wharfies had loaded the guns more speedily the guns could not possibly have reached Milne Bay and got into action before the end of the fighting, two days later, on 7 September. Simple chronology demolishes that argument.

Colebatch then makes a meal of the wirelesses used by Sparrow Force in Timor, offering pages of storytelling that turn out to be a fizzer. He claims that wharfies loading the ship that carried the 2/2nd Independent Company to Timor threw the troops’ wireless gear into the hold, damaging it. The 2/2nd arrived in Timor on December 1941, just after the outbreak of the war with Japan. The Japanese landed on Timor late in February 1942 and Sparrow Force had communicated with Australia in the meantime. After the invasion, when Sparrow Force’s survivors were waging a guerilla war in the island’s interior, they had no working wireless and cobbled together a Heath Robinson affair they called ‘Winnie the War Winner’, with which they re-established communications with Australia in April 1942. (This contraption is now on display in what Colebatch wrongly names as the ‘National War Memorial’. Not the only error – he has a ‘Dutch’ commander at Dili, in Portuguese ‘East’ Timor and the 2/2nd Independent Company was not disbanded after its Timor ordeal.)

Three prime ministers within two months, 1941: John Curtin, AW Fadden and RG Menzies (Australian War Memorial 042826)

Three prime ministers within two months, 1941: John Curtin, AW Fadden and RG Menzies (Australian War Memorial 042826)

What has any of this to do with union ‘sabotage’, you ask? Colebatch slyly implies that the wharfies’ rough handling of the 2/2nd’s gear in December resulted in the Independent Company’s isolation after the Japanese invasion. ‘I do not know’, he writes, ‘if there was a direct connection between the fact the watersiders were specifically reported … to have thrown radio sets into the hold and the fact that the commandos had no working radio after the Japanese attack’ (p. 23). But he implies that there was such a connection. Colebatch could not find any Sparrow Force veteran to claim that unionists irreparably damaged the force’s wireless gear. At best ‘not proved’.

Finally, Colebatch claims that a ‘wharf strike in Brisbane’ (undated and undocumented) prevented the 20th Brigade from carrying out a proposed rescue mission to liberate the surviving prisoners of war at Sandakan ‘because there were no heavy weapons’ (p. 4). But the 20th Brigade was never even considered for the proposed rescue mission, Operation ‘Kingfisher’. It was earmarked for the Oboe 2 landings at Balikpapan, which it carried out in July 1945. ‘Kingfisher’ had been outlined, using the 1st Australian Parachute Battalion (which neither had nor needed any ‘heavy weapons’) but was cancelled. The feasibility of ‘Kingfisher’ and the reasons for its cancellation have been vigorously debated among historians of the Borneo campaign but no-one has ever before mentioned the 20th Brigade or a supposed wharf strike as a factor. The usual villain is General Douglas MacArthur, whose headquarters is said to have diverted the necessary transport aircraft to American operations in the Philippines, though the definitive reason remains debatable. Colebatch’s claim adds nothing to the debate about the fate of the Sandakan prisoners. Verdict: irrelevant.

So the three supposedly scandalous cases Colebatch mentions in his opening chapters are all readily disprovable. Time after time the best that Colebatch can offer is a mixture of hearsay, implication and guilt by association. Many of the anecdotes he offers are vague, others irrelevant. Some are susceptible to reasonable explanations: for example, while a trained gunner might not quibble at handling inert shells, an untrained wharfie might well stammer, ‘B-b-b-b-but, that stuff’s dangerous’ (p. 39). Colebatch over-eggs the pudding by simply retailing, on page after page, a string of anecdotes, undated or corroborated, most sourced to ‘interview, April 1995’ or similar, with informants most of whom are now dead and unable to be further questioned.

We need to be fair. It is absolutely certain that many former Australian servicemen (as they remembered the war 50 years on, in the mid-1990s) harboured an abiding bitterness towards ‘unions’. It is less certain, but probable, that many of these men felt that way during the war itself; Colebatch quotes a few, very few, contemporary documents, such as the diary of Ronald Berry, a member of the 7th Division. What is by no means clear from his book, though, is whether unions or unionists actually did act as he claims, generally, widely or significantly. It is even more problematic whether unions (or unionists – he’s never that precise) actually ‘sabotaged our troops’. Sabotage implies deliberate, even directed, treasonable damage. Colebatch describes many incidents in which union members come out looking less than patriotic or honourable but this is hardly an impartial study.

One of the crucial questions with which Colebatch never quite grapples is why Australian unions or unionists would want to actively impede Australia’s war effort, at least after mid-1941. Between the war’s outbreak and the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 the Nazi-Soviet non-aggression pact meant that communist-dominated unions regarded the war as an imperialist struggle, which they declined to support. After mid-1941, though, ‘communists’ regarded the war as an anti-fascist crusade, in which the Communist Party of Australia became (as the Communist Review claimed in 1942) ‘the leading war party’. While trade union members did not necessarily follow their communist officials’ directions – they defiantly continued to engage in local disputes over pay and conditions, for example, to the officials’ embarrassment and anger (and to Colebatch’s fury) – the movement as a whole swung in favour of the war effort.

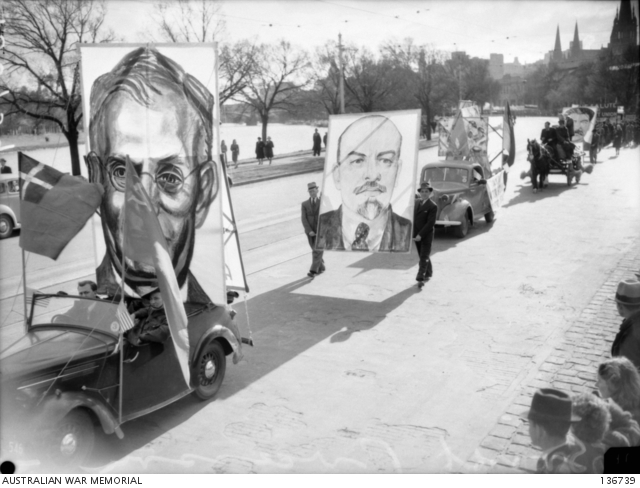

Paintings of Curtin, Lenin and Stalin in Anglo-Soviet Unity Procession, Melbourne, 5 September 1942 (Australian War Memorial 136739/Herald)

Paintings of Curtin, Lenin and Stalin in Anglo-Soviet Unity Procession, Melbourne, 5 September 1942 (Australian War Memorial 136739/Herald)

Unsubstantiated allegations that ‘communists’ obstructed loading or whatever make little sense. Or rather, they make no sense in the light of 1942-45 though they reflect the widespread and understandable repugnance felt by many Australians toward ‘communism’ after the war. Colebatch evidently never asked his informants how they recalled the Cold War or the Vietnam War, or how they voted in 1949 or 1975. If he had, he might have found that some of them projected their dislike of ‘communists’ from the 1950s and 60s back to the period when ‘communists’ were essentially on the same side as ‘us’. As historians have long understood, ‘oral history’ or ‘memory’ cannot be used so simply.

Colebatch barely recognises this profound change of attitude. The elderly ex-servicemen on whom he relied as ‘the foundation of the book’ (Acknowledgements; unpaginated) evidently did not see any difference between the ‘communists ‘ of 1943 and the same organisations (and often some of the same people) from, say, 1953, who truly felt no loyalty to Australia’s commitment to the cause of what was then known as the Free World. The result, to anyone who understands the convoluted history of Australian left-wing unions in the mid-twentieth century, is perplexing. Colebatch’s informants can be excused this lack of sophistication, but as author it was his responsibility to place their ‘raw’ memories in context, to explain what they meant. This he fails to do. He essentially simply repeats and endorses their charges but does not bother to check them, even when he could have.

Again and again, Colebatch repeats a man’s memory (usually 50 years after the fact) but without offering any corroboration. He repeatedly writes of ‘strikes’ but without making clear whether there really was an actual strike, whether it was authorised by the relevant union, recognised by the designated judicial authorities or was merely a bit of argy-bargy on the wharf. What Colebatch’s book documents beyond any doubt is that the services (army, navy and air force) had a very different attitude to the challenges of loading and unloading ships. As I wrote (in investigating charges that striking waterside unions impeded the loading of Australian troops bound for Borneo in 1945) – they did not: claims by ex-servicemen 50 years on turned out to be false; the wharves witnessed a clash of two very different work cultures.

Soldiers worked in energetic bursts and were paid regardless. They might be in action in Borneo within a couple of months but loading ships was one incident in their war service. Wharfies were paid only for the hours they worked, were concerned to protect their hard-won conditions and had to do the job for years. Of course, they had a different view about the demands made on them. For example, the ex-servicemen quoted by Colebatch were repeatedly scathing about the wharfies’ refusal to work in the rain. Young, fit soldiers worked in the rain (and lived and fought in it when called upon) but if they fell ill they were treated by the military medical system. Wharfies, usually older men, with dependent families, knew from long experience that risking illness meant losing work and, unlike soldiers, they had to pay for their own medical treatment.

Colebatch seems not to have appreciated the history of stevedoring workers or their unions. He paints them and their members as lazy, liable to skulk off for smokos or to pilfer from ships’ stores. And so many of them did; no-one who knew dockside work would deny this persistent abuse. But there is a gap between this low-level opportunism, even outright theft, and the ‘sabotage’ that Colebatch imputes.

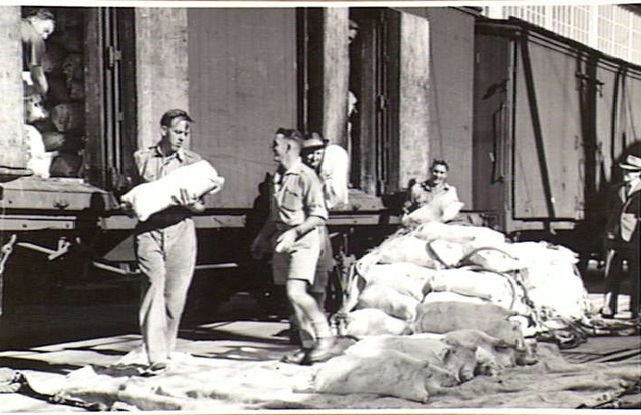

Army personnel unloading meat for soldiers at the front; during a wharfies’ strike, Sydney, 9 April 1943 (Australian War Memorial 050671)

Army personnel unloading meat for soldiers at the front; during a wharfies’ strike, Sydney, 9 April 1943 (Australian War Memorial 050671)

Some of the claims made by Colebatch’s informants are vague and impossible to check. But other incidents could be – and should have been – either verified or dismissed. Colebatch seems reluctant to consult contemporary newspapers. Chapter 10, on unrest in the New South Wales coalfields, is, for no obvious reason, the only chapter in which Colebatch quotes wartime newspapers besides his own father’s Northam Advertiser. This could be because Colebatch essentially wrote the book before the advent of the National Library’s Trove newspaper data base, which allows us to swiftly check many claims. For example, an informant’s claim that the headline ‘Wharfies Still on Strike’ appeared in newspapers ‘week after week’ (p. 105) can be disproved in .034 seconds as having appeared just once – in the Goulburn Evening Post on 30 March 1943 – and not at all in Queensland or Victoria through the entire war.

Astoundingly, while making claims about wartime disputes, Colebatch did not once check any allegations in any state or federal industrial tribunal records, whose files document wartime industrial relations in detail. Even when he claims that the August 1942 Premiers’ Conference discussed worrying industrial action, Colebatch failed to consult the easily available records of that meeting, or to give the statistics that might – or might not – have given the federal government and the premiers pause. As it happens, it seems ‘might not’ fits: press reports of the 1942 meeting made not even passing mention of industrial relations; perhaps it was not such a concern? But we don’t know. Astonishingly, for a book partly concerned with wartime governments’ relationship with unions, Colebatch fails to consult or quote any of the massive lode of government records available in national and state archives across the country, except for some Commonwealth Year Books.

Nor does Colebatch quote any of the mountains of union records freely available in archives. Ah, his defenders reply, why would he believe records kept by such un-Australian saboteurs? Perhaps. But Colebatch did not even test his criticisms against these contemporary records. And, as we often find, organisations and individuals so sure of their cause will often keep documents or correspondence that in time implicate them. Even the Nazis, for example, documented the Holocaust, because they saw nothing wrong with it. Tellingly, Colebatch refers to the notorious Wannsee conference (which essentially decided upon the Final Solution), but not the correspondence of the Waterside Workers’ Federation. (He argues that an Australian trade unionist who, say, requested a toilet break or payment for night work was ‘a conscious accomplice to the Holocaust’ (p. 181). A conscious accomplice?

Ludicrous statements like this abound and Colebatch’s arguments are often hard to follow; again, oddly, for a man plainly steeped in Western scholarship. But leaps in logic abound. On p. 197, for example, Colebatch decries that Australia designed and built only 66 cruiser tanks (‘which never saw action’) compared with Canada’s 222 ‘ram tanks’ [sic], which actually also never saw action. But surely this arguably wasted effort was entirely in the hands of managers, not unionists; what has this to do with unions’ alleged sabotage of the war effort? Colebatch slides from one aspect of the subject to another, often unfairly. For example, in discussing the 1940 coal strike, he acknowledges that it ended with a promise by the miners’ leadership pledging ‘industrial peace during the war’ (p. 118). In the very next paragraph he quotes John Curtin’s rhetoric, two years later under a different government, when Curtin warned (in the light of the Japanese threat) that ‘those who still won’t work for Australia will have to fight for Australia’. What is the connection?

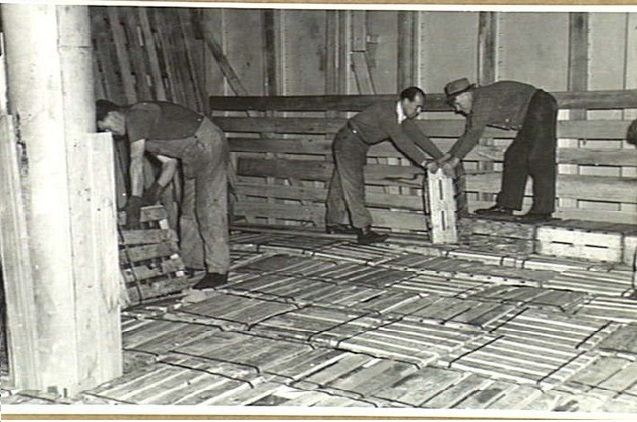

Waterside workers loading 75 mm shells into lower hold of MV Sarmiento, Sydney, 9 June 1944 (Australian War Memorial 06686)

Colebatch evidently regards any industrial action in wartime as a betrayal of those risking their lives on the battlefield. In this he echoes both extreme wartime rhetoric and the bitter memories of his informants. But to argue that this equates to ‘quasi-treasonous behaviour by the Australian Labor government’ seems to be an unconscionable leap. Colebatch disagrees with aspects of the Curtin Government’s management of Australia’s war effort (for example, by running down its armed forces from 1944 to transfer resources to production – at American request, it might be added). But what has this to do with alleged union ‘sabotage’? This seems far beyond the core of his argument, perhaps putting Colebatch on the loopy fringe of Australian history.

My initial critique of Australia’s Secret War published in the ABC’s The Drum was based on comparing the wartime relationship between unionists and service personnel by examining what happened on the Townsville waterfront when the 9th Australian Division staged through north Queensland ports to Borneo in 1945. Hearing ex-soldiers ‘remember’ strikes there in 1945 (in the mid-1990s – at the same time as Colebatch was researching his book), I looked at Australian military records, American archival sources and the records of the Waterside Workers’ Federation branch. I concluded that while there was friction between soldiers and wharfies, there was also collaboration and, contrary to ‘AIF folklore’, there had actually been no ‘strikes’. This presented a more nuanced impression that Colebatch could give, because he essentially accepted ex-soldiers’ memories without question and did not check them against other sources, archival or published. On p. 111 Colebatch quotes an ex-soldier who claimed that wharfies in Townsville were on strike in March 1945, a claim I had refuted in print in 1997 by referring to the primary sources.

Let me add to that critique another ‘case study’. The industrial town of Whyalla, on Spencer Gulf in South Australia, was transformed during the war from a little ore-shipping port into a major iron smelting and ship-building centre, whose population increased from 700 people to about 8000. Whyalla’s experience offers a test of the involvement of unions and their members in wartime and became the basis of both my ANU Litt.B. thesis in the early 1980s and a book, Whyalla at War 1939-45, published in 2004. Whyalla is mentioned just twice in Colebatch’s book. On p. 145 he writes ‘in 1936 BHP started to build an iron and steel plant and shipyard at Whyalla … However it was not to commence steel production till [sic] 1941 or shipbuilding till 1942.’

Actually Whyalla’s first keel was laid in 1940 and the first ship was launched in 1941 but Whyalla did not produce ‘steel’ at all until 1965. The ‘facts’ are wrong. But more importantly, is Colebatch insinuating that the seeming delay in commencing production was due to union intransigence? The contemporary sources would not support such a view, but after 145 pages critical of unions Colebatch’s implication seems clear.

In any event, Whyalla provides a useful test of Colebatch’s argument, because, unlike his claims about lazy coalminers and treacherous wharfies, Whyalla’s experience is abundantly documented in corporate, union, government and newspaper sources. What we find in Whyalla is that about 2000 of its 2500-strong workforce were unionists, co-ordinated by a strong Combined Unions Council which lobbied BHP in both workplace matters and in running the township (which had no elected local government until 1945). Every ton of iron ore won in Australia was shipped from Whyalla’s ore jetty and the new shipyard built four naval corvettes and seven merchant ships.

Communist Party members and sympathisers, Anglo-Soviet Unity Procession, Melbourne, 5 September 1942 (Australian War Memorial 136737)

Whyalla’s workers suffered 9000 industrial accidents – virtually one per worker employed there, 3000 of them classified (by BHP) as ‘serious’. There were tensions between the more conservative craft unions and the communist-dominated ironworkers and waterside workers; BHP and several unions remained locked in an adversarial industrial system. But ‘contrary to popular mythology’, I wrote in 2004, ‘the war years were not riven by strikes’, though many small-scale disputes occurred, often in defiance of communist officials, who tried to get men back to work. Many arguments arose over the ‘dilution’ of skilled work by un- or semi-skilled workers, or over ‘demarcation’ disputes. ‘There was stubbornness on both sides’: in 1945 the Ironworkers sought payment for the few minutes it took them to collect their pay, but at the same time BHP officials were concealing from men that they were entitled to an allowance for working in confined spaces. Colebatch observes on p. 196 that Whyalla’s shipbuilders were former farmers and ‘less imbued with the union culture’. Some were, but the ironworkers and wharfies’ officials were committed unionists.

Did Whyalla’s unionists ‘sabotage’ Australia’s war effort? There was one reported case of actual sabotage, in 1940, during the period when communist-dominated unions deprecated the ‘imperialist’ war (a kerosene-soaked towel was found in a burnt-out carpenters’ shop). While absenteeism remained a problem – shops and banks opened only when men were at work, so single men felt obliged to take time off if they needed either service – the war’s only major protest occurred when tobacco supplies ran short. Whyalla was often criticised for failing to meet war savings targets, but it was a town of new residents where money which in more-established towns went to buy war bonds was used to build or furnish new houses.

On the other hand, Whyalla’s residents – overwhelmingly union members and their families – joined and supported a great range of voluntary war groups, including the Red Cross, the Fighting Forces Comforts Fund, the Cheer-Up Hut (looking after the AIF anti-aircraft gunners posted there in 1942), as well as specifically left-wing charities such as the Sheepskins for Russia appeal. The town’s established residents, many of them BHP staff, tended to organise the voluntary war effort, but their members and supporters were mostly workers and unionists. Most tellingly, while most of Whyalla’s workers were prevented from enlisting in the forces by the Manpower regulations (something that Colebatch hardly mentions) hundreds joined the air raid organisation in 1942, the year when attack or invasion seemed possible, while the Volunteer Defence Corps (VDC) quickly recruited over 300 men, many of whom also worked 10-hour days and six-day weeks. Moreover, as the VDC took over responsibility for the anti-aircraft guns in 1943 the town’s VDC maintained a commitment for longer than most VDC units. Colebatch fails to take into account efforts such as these, instead focusing only on anecdotal and mainly retrospective accounts of strikes.

When in 1944 BHP at last decided that it needed to hand responsibility for the town to a local government, unions took a prominent part in negotiating the new arrangements (a ‘Commission’, part elected by residents, part appointed by the Company, under a government-appointed Commissioner). In the elections for the Commission, residents elected Eric Stead, a communist candidate, as one of the first three elected representatives. (‘[N]aturally, we are not very pleased with the result’, BHP’s local manager wrote to head office in Melbourne.) In a war fought to preserve democracy, the people of Whyalla chose in Stead a man they knew; they did not see him as a faceless ideologue. Their experience, taking in years of hard work, some hard-fought industrial contests (with other unions as well as BHP), support for the voluntary war effort and the creation of a novel form of local government, seems a more balanced and representative account than Hal Colebatch’s concentration on anonymous wharfies sabotaging the war effort for no very clear reason.

Finally, it is worth recalling that while Whyalla acquired a reputation as a ‘white feather town’ (because Manpower rules prevented industrial workers volunteering) over 500 of its men and 23 women did serve in uniform, about a third after the wartime production boom eased in mid-1944. Of them 29 died, in north Africa and the Pacific, in HMAS Sydney and in the air war over Europe. It seems that about a quarter of them at least had been members of unions. Hal Colebatch largely fails to remember men like Jack Glass, an engine-room attendant killed at Gona or Norman Frick, an ironworker killed on the Huon peninsula, or William Wood, a stores clerk killed after a raid on Stuttgart. Colebatch belatedly recognises (on p. 302 of a text of 305 pages) that ‘other men and women of the Australian working and artisan class in World War II performed prodigies of valour and self-sacrifice’. By this stage of the book (three pages from the end) this concession has little effect.

On p. 192 Colebatch regards as ‘grotesque’ that unionists at the Midland railway workshops in 1943 sought holiday pay to mark Anzac Day, a privilege many of us enjoy today. Colebatch’s scorn exemplifies why he has failed to understand the full story of unionists and Australia in World War II. He writes as if Australia could simply be divided between those who served their country in uniform and those who ‘sabotaged’ it through industrial action. He fails to grasp that a good proportion of the uniformed services – somewhere between a quarter and a third – comprised men and (to a lesser extent) women who had themselves been unionists, many of whom would, after war service, return to their jobs and to their unions, and see no contradiction in that. He fails to recall that relatives of the unionists he decries also served.

One of the comments on my piece in The Drum came from a man who had been born in Townsville just after the war. ‘My grandfather was one of the wharfies there during the entire war’, he wrote. ‘He had three sons fighting in New Guinea, so an accusation that my grandfather would do anything to sabotage the war effort is just despicable.’ This man’s family history underlines the complexities of the relationship of ‘unionists’ in wartime Australia, complexities and ambiguities which Hal Colebatch failed to discern or acknowledge.

Despite his academic qualifications, Hal Colebatch is no scholar – not in this book anyway. Rather than enquire into the question ‘how did unions support the war effort, or otherwise?’ – which could have led to a more nuanced book – he has produced a tendentious account, skewed by failures to locate or interrogate evidence and a willingness to believe anything bad of unions, regardless of how flimsy the evidence (or even how disprovable it is: see Sandakan, Milne Bay and Timor, above). This is a badly flawed book. And that’s a pity, because Colebatch not only shows that at least some unionists introduced tensions into the wartime economy and society but also suggests that the full story has yet to be told. But, if it is to be told, it needs to be done by a less partisan historian, one with a more finely-tuned approach to a broader range of evidence, and one able to consider it in its historical context, without anticipating the conclusions reached.

So, finally, in answer to Hal Colebatch’s question, ‘Who are the liars?’ the answer is: nobody. Nobody is actually lying. The wartime memories Colebatch quotes may be wrong, but they are honest mistakes: John Collins did get annoyed at dockers who messed him about; Bernard Callinan accurately recalled his frustration at wharfies who failed to work as efficiently as he wanted them to. Colebatch’s informants may have been confused but they were surely sincere. But that does not mean that all of them were telling the whole, literal, absolute truth.

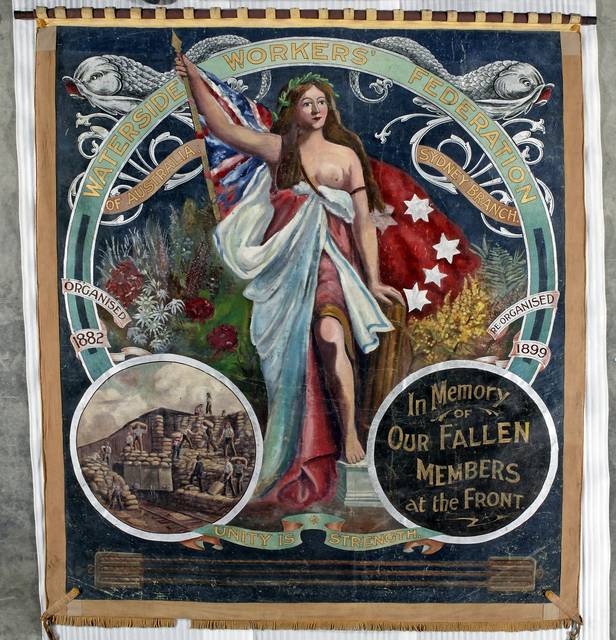

Waterside Workers Federation of Australia, Sydney Branch, about 1920, banner acknowledging waterside workers killed in the Great War (National Museum of Australia MA23148353)

Colebatch’s witnesses were recalling aspects of their experience, and mostly long after the war, influenced by the events of a lifetime in which suspicion and even hatred of ‘communists’ and ‘unions’ may have resulted in some memories being accentuated and others suppressed or skewed. Colebatch is not lying either, but he has allowed ideology to unduly distort his exploration of what occurred. His failure to ask crucial questions of the evidence is culpable, as is his failure to check or corroborate the version of events he was told. This confirms my judgment that Colebatch’s book does not deserve to be recognised as it has been by an award that suggests that the author operates as an historian at a high level. But is Colebatch lying? No; his book is just a genuine mistake.

Professor Peter Stanley is President of Honest History. He is a Research Professor in History at the University of New South Wales, Canberra, the Australian Defence Force Academy. He has written nearly 30 books, most of them on social-military history, and in 2011 was joint winner of the Prime Minister’s Prize for Australian History.

* Quadrant Online has now (20 December) linked this piece, for which we thank Roger Franklin. HH.

Having not quite finished reading this above book(todays date 07/04/2020).

My father in-law, when he was alive reminded my sons and I of the goings on in the waterfront in Darwin as he was in New Guinea during WW2 and he related on events that happened.

Which by strange coincidence do correspond to most events portrait in the book.

These events turned him into a bitter non Union person as when returned after the war to the family business, there the were to be no union activity at all.

My two and only crossing of paths with waterfront workers,

1st in Sydney in the late 60’s my favourite drinking pub at the time was the “Forth & Clyde” Balmian Friday nights were great social events, on one occasion I was approached by a member of the waterfront workers and he was discreetly walking about the pub offering bottles of whiskey to pub customers unbeknown to the licence of the pub at $1 per bottle, but you had to buy a case of 12 from him, I told him I’d take 1 as my mode of transport was a motorcycle he told me no.

At the same time a bottle of Johnny Walker black label was going for about $7, it was only latter thinking about it I and the closeness to the waterfront and speaking to others it was as you say fallen of the back of a truck.

next….

2. I worked for a IGA type of store in Darwin in 1976 and used to go with the owner to the airport/waterfront to pick up the stores shipment of fresh cherries and fruit, and while we walked into the area to pick the boxes up waterfront men were walking out past us with paper bags full of cherries etc.

When we picked up the boxes they were opened and you could see pilfering was going on to all the boxes,I spoke to the manager and asked him why don’t you report these events (as it was quite common for fresh fruit boxes to be pilfered) the manager told me if he reported these events to the authorities they the waterfront workers would ban and not handle his shipments and leave the fruit to rot.

It’s a real shame that this was not put to the men/women serving in the forces to say their piece just after the war to verify events, but then censorship by Govts of the time do stifle the truth.

I have been on this spinning planet for 71 years and have seen it all.

Cheers have an open mind.

I’m no critic or academic, however, I’m surprised at the Lord Haw-Haw piece here. It’s a wonderfully written piece. (I wish I could do half as good. I’d eat twice a day with that production quality). Nonetheless, having been associated with a number of people over the years from a service and union background because of my union membership, I have to accept what Mr. Colbatch has offered.

Yes, it may be poorly written, but perception is reality, and the facts may not line up like little duckies, but the assiduous and hyper-criticism of The Secret War does not add to the clarification of that particular history.

It’s also been my experience that ‘academics’ simply live to dissect the hair off a bee’s arse and write reams of information that reveals what is obvious. It’s a hair off a bee’s arse. And not actually looking at what the whole of subjuect involved. As one wry Scotsman said to me once when I was demonstrating just how much I didn’t know, and, on quoting a ‘specialist’ he retorted, ‘A specialist is someone who studies more and more about less and less; until they come to know everything about nothing’.

“Mmmm, by George, I think he’s got it”.

This assiduous, dainty and precious criticism is very tedious to the point of being twee.

Well done …. like you, I think this book is “just a genuine mistake”. A soon to be forgotten one as well. “History”? No, short-sighted printed ideology.