‘War dances and real wars: Honest History First Peoples miscellany’, Honest History, 7 June 2015

Update 8 June 2015: Helen Davidson writes about Wayne Quilliam’s photographs of and interviews with the women of Indigenous Australia. Quilliam’s exhibition opens at UN Geneva on 17 June. Paul Daley on moves by Indigenous Australians to renounce their citizenship.

________________________

Guardian Australia writer, Paul Daley, sat in on (and wrote about) a meeting between retired Aboriginal Affairs bureaucrat, Barrie Dexter, and his former activist antagonist, Gary Foley, who have collaborated with Edwina Howells on editing Dexter’s autobiography, written many years ago and now published.

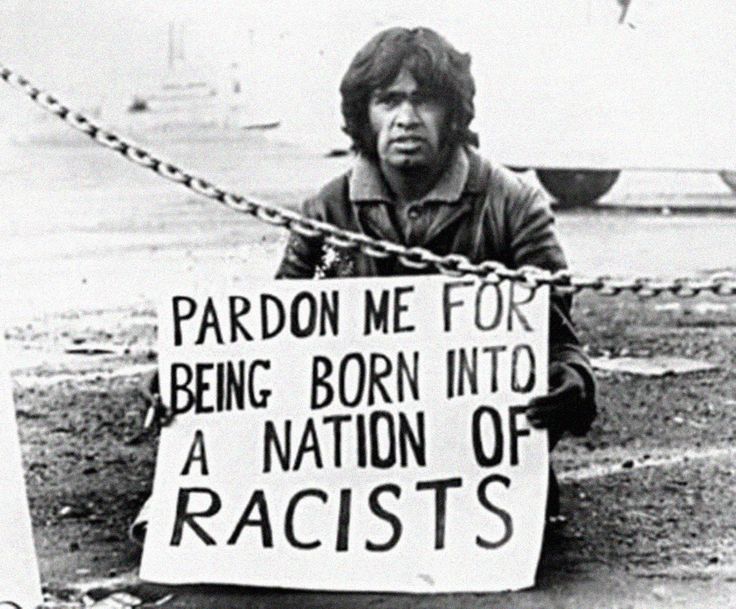

Gary Foley c. 1971 (Pinterest)

Gary Foley c. 1971 (Pinterest)

Dexter is optimistic for the future of Indigenous Australians, Foley more pessimistic. Dexter believes a 1967 referendum held today would pass, due to the wider knowledge of maltreatment of Indigenous Australians but ‘while much the same number of Australians would be in favour of doing something, the percentage that know what to do is still much the same as at the time of the referendum’. Foley, on the other hand, believes ‘attitudes have hardened’, as seen in the treatment of both Indigenous Australians and asylum seekers and due to the influence of Pauline Hanson and John Howard.

Larissa Behrendt assesses Foley’s career as activist, actor, writer, and teacher. He recently won an award for his doctoral thesis. ‘Gary Foley’s renaissance is a reminder’, says Behrendt, ‘of the interplay between the arts and the agenda for long-term and important structural change; between protest in the street and an intellectual agenda for societal transformation’.

The AIATSIS website has a comprehensive history of the 1967 referendum. There is discussion of the issues, the campaigners and the result, with links to further resources.

The overall “Yes” vote was 90.77%. The “No” vote was largest in the three States with the largest Aboriginal populations. In Western Australia 19.05 per cent voted against, in South Australia 13.74 per cent and in Queensland 10.79 per cent. In New South Wales the “No” vote was heaviest in the country electorates with racial problems.

The AIATSIS site also carries the speech by Bunuba woman, June Oscar, at the opening of the British Museum’s ‘Enduring Civilisations’ exhibition of Indigenous works. Much of her speech was about the Indigenous warrior, Jandamarra.

Jandamarra wanted the best of both worlds [she said], and this is still what we strive for today. In achieving this we cannot fail to grasp the deeper meanings of Jandamarra – that we are stronger when we act together. That we make better and smarter decisions when we do it together. When we acknowledge the wonderful, complex worlds of others we embrace our humanity we do not forsake it. This is the journey of reconciliation. In holding Jandamarra close, we can travel this journey with his spirit of fierce resistance, rebelling against all forms of injustice, domination and inequality.

Paul Daley writes about a Canberra exhibition of photographs of Indigenous rock art from Arnhem Land.

Perhaps the first thing you’ll notice [at the exhibition] is the number of guns depicted in the Bininj art that adorns countless rock faces and caves across thousands of kilometres of the Arnhem Plateau, which Guymala and his fellow rangers are fighting to protect from the elements and feral animals, especially pigs and buffalo. And that is precisely what the Bininj noticed too, and recounted on returning from the frontier to their people when they effectively reported on the walls what they had seen of the white man and his curious ways.

Myall Creek Massacre by Pro Hart (Artrecord)

Myall Creek Massacre by Pro Hart (Artrecord)

Guns signify conflict and there was an echo of conflict in the celebratory ‘war dance’ performed by footballer, Adam Goodes, on the field. Amy McQuire summarised the reaction. ‘For the most part’, she noted, ‘sporting contests represent a safe space where white Australians can access black Australia, devoid of the uncomfortable truths that they have had to overcome on their path to sporting glory’.

Further commentary came from Chris Graham, also in New Matilda, Andrew Bolt in the Herald-Sun, Martin Flanagan in Fairfax, and Waleed Aly on television. Graham’s summing up was perceptive:

Goodes, like Freeman is very much a winner, so in theory we should love him. He’s a dual Brownlow and three times Bob Skilton medalist, a four-time All-Australian, has been named as part of the Indigenous Team of the Century, and has twice won the AFL grand final, including guiding his team to victory in 2012 as captain. By any measure, Goodes embodies sporting success.

But in a sporting nation that routinely denies its history, straying from footy into politics and reminding the non-Aboriginal population of the collective sins of our past is never going to endear you to the masses. You don’t win popularity contests with raw truths, particularly not if you’re a black man.

Goodes’ occasional challenges to racism grind and burn at mainstream Australia. But Freeman’s act complimented our national story. It was an act of reconciliation – ‘I love both flags, I love both people’ – and allowed us to feel precisely the way we collectively like to see ourselves: as a tolerant and inclusive nation, where everyone is equal, regardless of their race, religion or sex.

The fact is, we can’t just pick and choose the parts of our national story that we like, and you can’t have reconciliation without truth. It’s precisely those truths, and Goodes’ role in speaking them, that brings into sharp focus the importance of his approach.

On the eve of the anniversary of the Myall Creek massacre in 1838, Paul Daley, again, wrote about some of these truths. Timothy Bottoms spoke at last year’s anniversary and Professor John Maynard has the task this year.

It seems a strange and hypocritical contradiction [says Maynard] that some black and white politicians tell us we need to “move on” and not dwell upon the frontier wars of the past whilst at the same time we are saturated with “Lest We Forget” Gallipoli – a failed (allied, including Australian) invasion of another peoples’ country. Myall Creek and Coniston are two of the more prominent Aboriginal massacre sites and as such stand as markers not just for the horrific crimes that took place at these locations but reflect additionally the multitude of silences that remain across the wider continent.

I think for me having the honour to speak at the Myall Creek Memorial this year I will certainly reflect not just on those who lost their lives at that site but use the location and day to remember all of those who lost their lives in places forgotten, missed and purposefully erased from both memory and the record.

Adam Goodes (9News)

Adam Goodes (9News)

Meanwhile, back in Canberra, the Australian War Memorial holds the line against commemoration in that national institution of these defining battles in Australian history.

In a practical sense, by the way [said Memorial Director Nelson], we are not of the view that there was such a thing as a declared war against Indigenous Australians. After the British garrisons left, where the violence occurred it was conducted by police militia, some pastoral militia and mounted Aboriginal militia. Also, from our point of view, the strength of what we do at the memorial—and Senator Back referred to it in his introductory remarks—is our collection: the things that we actually have. Even if the War Memorial were of the view that it should be telling the stories of armed conflict, we do not have any collection to do it. (p. 120)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.