‘Professional Historians Association Historically Speaking series, 5 April 2016: Reflecting on the Anzac centenary and memorialisation’, Honest History, 13 April 2016

I’d like to begin my reflections by acknowledging the size of the audience for the World War I: Love & Sorrow exhibition at Melbourne Museum since it opened in August 2014: over half a million visitors. Of those surveyed, 97 per cent said it made them think of the cost of war; 89 per cent said it made them consider new things; and 72 per cent said it gave them new perspectives.

For those of you who haven’t seen the exhibition, I’ll begin by telling you a little about it, then address the questions posed for this evening. Located at Melbourne Museum, it follows the stories of eight real characters through the chronology of World War I and the post-war years, focussing on the cost of conflict borne by soldiers, families and communities. It was underpinned by a desire to present a more graphic account of the war, using new or under-utilised approaches to presentation. It was also underpinned by the belief that the exhibition could make a difference to the way we remember and engage with World War I.

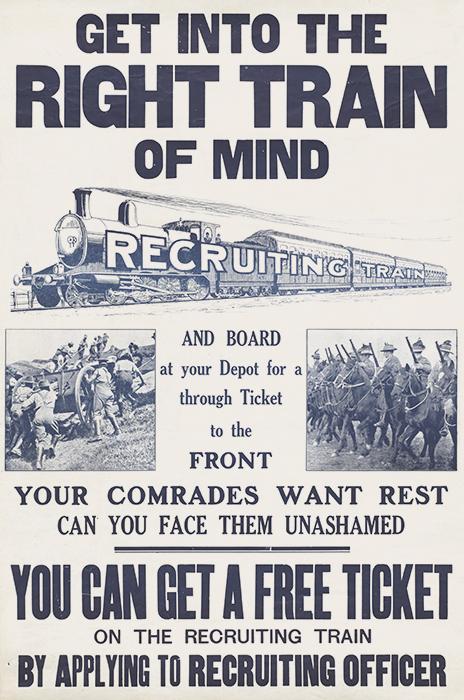

Recuitment poster, Love and Sorrow (Museum Victoria/NLA)

Recuitment poster, Love and Sorrow (Museum Victoria/NLA)

All histories, of course, are works of imagination and the product of the interchange of ideas. I was particularly influenced by Marina Larsson’s Shattered Anzacs, which I began to read as I took over co-curation of Museum Victoria’s military history collection with Charlotte Smith. I became determined to present the stories in the collection – through an exhibition – using this sort of lens.

Working out how the stories would be presented in the most engaging and powerful way, I came across Peter Englund’s terrific book The Beauty and the Sorrow: an Intimate History of the First World War. He follows about 20 stories through the chronology of the war, using the words of the participants as they twist and twine through time.

The real power lies in the unfolding narratives – we don’t know what’s going to happen to each person. The thing about being a historian is that we know what’s going to happen, so the narrative loses some of its power. Putting the reader or visitor into the position of not knowing immediately adds anxiety, puzzlement, questioning – and engagement. And so it was that I approached Love & Sorrow, as a series of unfolding parallel narratives with unknown outcomes, structured to build emotional engagement. (We know people are more receptive to ideas when emotionally engaged.)

It’s the approach of the film-maker, and in other ways the exhibition is deliberately film-like too. It begins with a few ‘trailers’ or teasers – objects in separate displays before the start of the exhibition, posing questions to start the visitor thinking in new ways about the war – such as ‘How would you mow a lawn blind?’ and ‘Could you spend 43 years in this bed?’

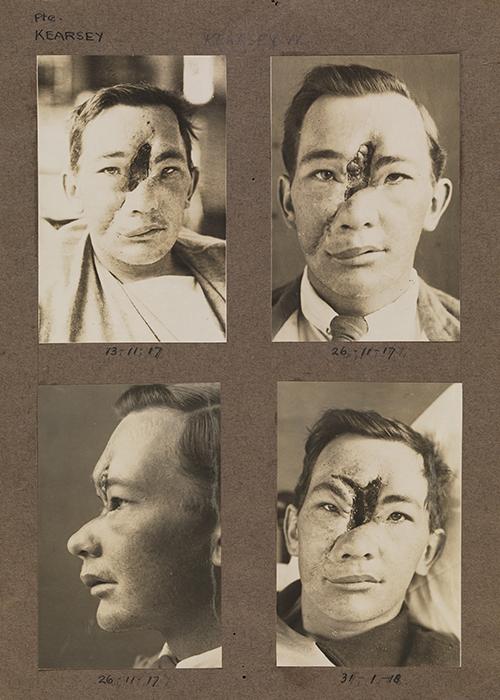

On entering the exhibition, you meet the eight key characters and become committed to their stories. You follow the chronological trail of the exhibition to a sort of climax in the middle with an interactive of a battlefield, Glencorse Wood in Belgium, and also a section about facial wounds. The exhibition ends with a series of short films of family members reflecting on their loved ones and war.

The exhibition also includes a hand-held device, ‘The Storyteller‘, on which visitors select one of the eight stories to follow, hear readings from diaries and letters, and access contextual information as they move through the space. It was very important that the choice of stories reflected diversity: of gender, economic status, ethnicity and age. We included a mother who sent her beloved son to war, two Aboriginal brothers, a butcher with a young family, a coach-builder, a teenage telegraph messenger, a recently-married orchardist, and two German-Jewish brothers.

Our stories were based on people represented in our own collection and some who had been research subjects for our academic advisory committee: Professor Joy Damousi, Professor Al Thomson, Dr Bart Ziino, Dr Kerry Neale, Professor Peter Stanley, and Dr Marina Larsson herself.

As well as these key stories, we covered some broader content too – showing, for instance, diversity of ideas, acknowledging those against the war and those interned. And we haven’t only drawn on intimate personal sources: for instance, with Glencorse Wood and the Sidcup hospital for facial wounds, and footage of shellshock on the device, we step into a shared arena of tragedy. A hand-held device triggers as visitors move through the space, providing the growing toll of casualties as time passes.

Bill Kearsey, Love and Sorrow (Museum Victoria/Royal Australasian College of Surgeons)

Bill Kearsey, Love and Sorrow (Museum Victoria/Royal Australasian College of Surgeons)

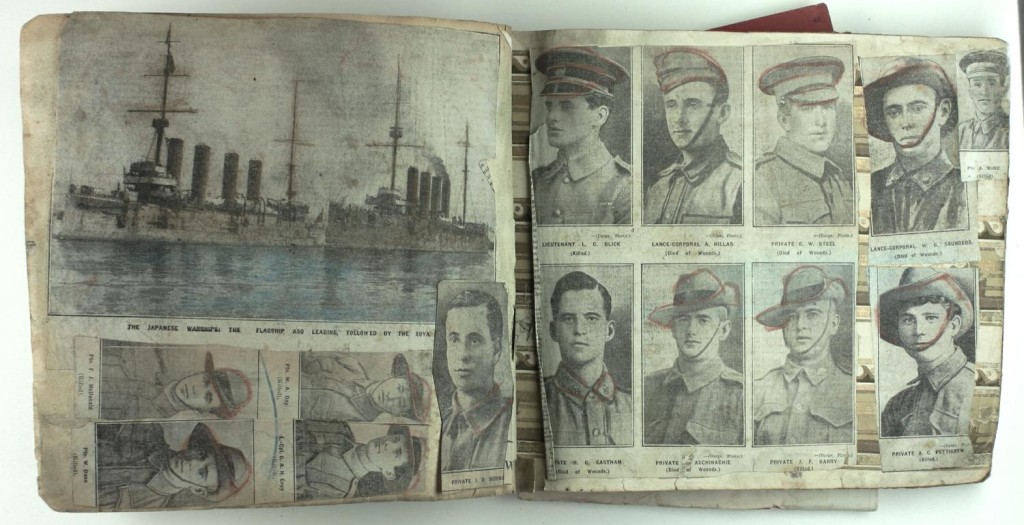

At no point, though, have we tried to tell a more complete narrative of the time. A little exhibition like Love & Sorrow can only tell one small corner of an enormous story. In a sense I wanted to break the large narrative of war into little pieces, loaded phrases, intimate objects and photos filled with personal meaning.

Now to address the questions posed for the panel this evening. I’ll first consider how communities have made, and expressed, meaning through the exhibition, and contributed to the centenary. The challenge here is that the type of history I do is very much ‘led history’ – in a sense, I have a broad notion of what should be said and needs to be said (exhibitions have pre-determined messages) – then I reach outwards to ‘authentic participants’ to provide commentary, context and content. I put out an invitation to families from whom we hold collections, or to historians or curatorial colleagues who have worked with particular people or communities, and I invite them to come to a place or space where they can tell stories and make further meanings.

In Love & Sorrow, there were a couple of important points where this happened: in informal discussions with families, where we talked broadly through the known stories and built meaning around objects; and in the formal filming process, where I interviewed one family member for each story, and invited them tell the story of their loved one’s involvement in the war and post-war years, in their own words. Daybreak Films was filming each interview. During the filming session each person also re-voiced the words written so long ago, so that they would be delivered in the exhibition by those for whom they had the most power, and for whom the most meaning was held.

Of course for me and my colleagues, Marina Larsson (who joined us on staff for a time) and assistant curator, Liz Bramley, the contextual information we were able to gather to authenticate and build these stories was critical. In addition to the usual primary sources such as the National Archives and contemporary newspapers on Trove, and secondary sources, we had the benefit of collections at Museum Victoria, other collections such as the Australian War Memorial, and family collections, too. This is our core business at Museum Victoria: using material culture to shed light on the past and working with communities and a plethora of other sources to contextualise and make sense of the material.

The next question for this evening considers how centenary initiatives have furthered our understanding of World War I. I’m going to focus my response again on Love & Sorrow. War is about violence; there is much that is still almost too terrible to contemplate about it; and its impacts lasted for generations, and still reverberate today.

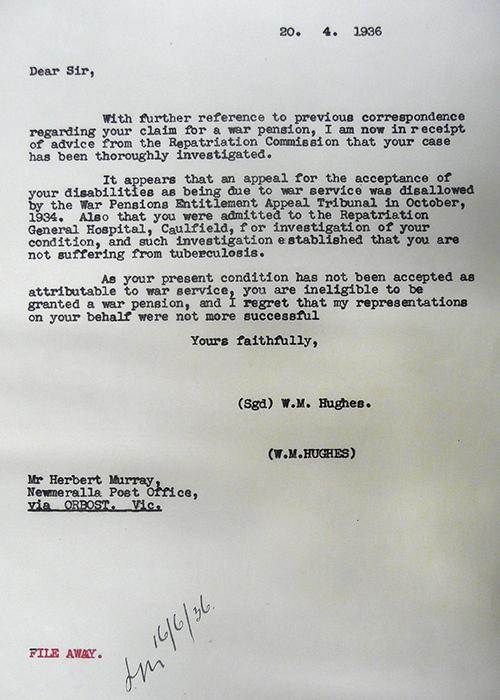

Personally, I find there’s a need to be more complete and open in our depictions of war. For Love & Sorrow, I wanted to tackle those things which were hardest to face at the time of the war and still remain hard: facial wounds, sexually-transmitted diseases, mental illness and suicide, and lifelong illnesses such as TB. Looking directly at grief, although heart-breakingly painful. I wanted to begin to break down the ‘us and them’ attitude that underpinned the war, as it does by necessity all wars, and to show mothers grieving the same across the divide between armies, and soldiers buried together, no matter for whom they fought.

And then there are physical acts of violence. Jay Winter long ago pleaded that we might only show weapons of war when we showed what weapons do – which we’ve done for the Glencorse Wood interactive, the growing landscape of desolation and destruction, above which points a Stokes mortar and a small cluster of other killing apparatus. The visitor’s shadow appears in the landscape and disrupts it, opening a view to the next layer of time.

Australians, Menin Road/Glencorse Wood 1917 (Wikimedia Commons/SLQ)

Australians, Menin Road/Glencorse Wood 1917 (Wikimedia Commons/SLQ)

I’ve become very conscious of what’s missing from depictions of war, particularly in leading institutions such as the Australian War Memorial’s new World War I galleries. There are still almost no dead, few maimed (although a little display acknowledges the facial wounds treated at Sidcup). There are no grotesque body parts, although some were ‘sampled’ and are still preserved as specimens in public collections in Australia. There are no bone-collectors, no killing fields. But – what’s war about, if not this?

For me, the most powerful part of the AWM’s World War I exhibition is a small, dark space at the end where they acknowledge mourning, post-war struggles to cope with wounds and memories, and long-term impacts. If only there was more like it.

Another aspect of Love & Sorrow I want to draw attention to is the avoidance of any reference to nation-building, and none of the quasi-religious language that’s so often used to describe war, still so pervasive 40 years after Paul Fussell pointed this out in The Great War and Modern Memory. The word ‘sacrifice’ never appears in the exhibition; soldiers do not ‘fall’ but are blown apart or buried alive or drowned.

Speaking of the quasi-religious, the word ‘Anzac’ is little-used in Love & Sorrow, except where it appears on objects and writings from the time. Gallipoli appears as one small but poignant case, featuring the diary of Corporal Siddeley of the Australian Army Medical Corps, who is rare in his heart-broken, immediate descriptions of the terrible wounds he helped to treat. He too was to suffer long after the war, finding his memories almost too much to endure. Gallipoli is presented as a site of violence and despair, ending in retreat.

Another thing many of us have reflected on is how to show our historical characters sympathetically (perhaps admiring their resilience or their loyalty) but also to show their flaws: participating in vicious battles, killing and maiming, falling to pieces amidst the horror of war, busting into tears, breaking down, flinging angry truths at the authorities. And children, too, victims of circumstance but sometimes culpable too, like those who taunted Eric Winter, whose jaw had been blown away. It’s not our job to whitewash anything, however complex or unpleasant it makes the past seem.

Letter advising of failure of claim for war pension, Love and Sorrow (Museum Victoria/NAA)

Letter advising of failure of claim for war pension, Love and Sorrow (Museum Victoria/NAA)

The notion of ‘mateship’ is also scarcely visible in the exhibition amidst the strong familial bonds – reflecting, in part, the nature of our source material. There are moments of it, though, like the letters written by fellow soldiers to John Hargreaves who is suffering through treatment at Mont Park, sent back to Australia in a state of total mental collapse. They write of mademoiselles and scabies and woundings and sickness, with all the gravity of a comedy review. Their words pale beside the family’s account of John’s experience.

Remember, too, even the words of soldiers, written at the time they were lived, are filtered by the hands of descendants, and it’s rare to find any letter or diary that’s critical of those at home, expressing unpopular or unsavoury ideas, documenting descents into mental oblivion or the terrors of wounds, disease and mortality. There are glimmers of these things, or coded references, but rarely more.

One letter in Museum Victoria’s World War II collection is a striking example of this. It was one of a collection of letters found stuffed under floorboards at the Royal Exhibition building by World War II soldiers, never meant to be preserved. This particular letter begins by expressing personal frustrations about betting on horses and cards, and the disappearance of a knife, descending into two pages of foul abuse. Frankly it’s all very unpleasant. It’s hard to do unpleasant history.

With war, we have to resist the temptation, I think, to make something positive out of it, to suggest that a nation is built, an honourable sacrifice is made, medical advances were remarkable, families make do, society holds together, we all move on. In fact, none of these things come close to making war justifiable.

One of the things I found interesting about my colleagues’ response to the concept of the exhibition – which was largely positive – was concern that the exhibition would be a ‘downer’. Our traditional wisdom is that museums are uplifting: knowledge grows, insight comes; perhaps we might hope to have fun or be entertained. And so a visit ends. My argument is that we need to include the not-so-good bits too. It’s OK to leave an exhibition about war feeling sad, upset or grieved, or confused. In fact, if you felt otherwise, the exhibition would have failed in its purpose.

I hope we can contribute to breaking down the blanket of civility, respectability and comfort that is wrapped around the act of war. I feel very encouraged by visitor responses to Love & Sorrow, which so strongly express an aversion to war, often a new aversion – ‘I didn’t realise…’, and has had significant impact on younger visitors.

Support for our more complete and graphic accounting of World War I has come from less expected quarters too, such as the Victorian RSL and the Victorian government (both major parties) which funded the exhibition. Responses indicate that academic – or at least museological – representations can have some impact, some deepening engagement with the less palatable experiences and meanings of war.

Finally, to contribute to our discussion, a couple of questions. How can we keep the distress of war front and centre, and not pushed into the shadows? How can we remember that war is an act of violence? As Joy Damousi has suggested, what patterns of behaviour can we see in families today that may be rooted in the dysfunctionality brought home by disturbed veterans 100 years ago? A sort of dark centenary within families. Now that’s a centenary we really need to mark.

Deborah Tout-Smith is Senior Curator, Museum Victoria, and Lead Curator, World War I: Love & Sorrow exhibition

Child’s scrapbook 1915, Love and Sorrow (Museum Victoria)

Child’s scrapbook 1915, Love and Sorrow (Museum Victoria)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.